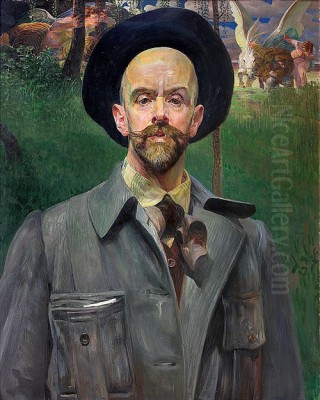

Jacek Malczewski stands as a monumental figure in the history of Polish art, widely celebrated as the father of Polish Symbolism. Born on July 15, 1854, in Radom, then part of the Russian Empire, and passing away on October 8, 1929, in Krakow, his life spanned a period of immense political turmoil and cultural resurgence for Poland. Malczewski's vast body of work masterfully intertwines national history, folklore, mythology, Christian tradition, and deeply personal reflections on life, death, and the nature of art itself, leaving an indelible mark on the cultural landscape of his nation and beyond.

His unique artistic language, characterized by its rich symbolism, dramatic compositions, and often haunting beauty, emerged from a complex blend of academic training, exposure to European art movements, and an unwavering connection to his Polish roots. Through his paintings, Malczewski not only captured the spirit of his time but also forged a path for modern Polish art, influencing generations of artists who followed.

Early Life and Formative Influences

Jacek Malczewski was born into a noble Polish family, although their financial standing was described as modest. His upbringing was steeped in patriotism and intellectual curiosity, largely thanks to his father, Julian Malczewski. Julian was a known patriot and social activist whose deep interest in art and literature profoundly shaped young Jacek's worldview and artistic inclinations. This environment fostered an early appreciation for Polish culture and history, themes that would become central to his later work.

The family's circumstances reportedly became more difficult following his father's death, potentially contributing to the artist's lifelong preoccupation with themes of fate, mortality, and hardship. Furthermore, his childhood was marked by personal tragedy, including the early death of a brother, an event that cast a shadow and likely deepened his sensitivity to loss and melancholy, recurring motifs in his art.

Adding to his formative influences was his uncle and long-term guardian, Feliks Karczewski. A writer himself, Feliks's evocative descriptions of the Polish landscape and its rich folklore captured Jacek's imagination, planting seeds for the fusion of naturalism and symbolic fantasy that would later define his style. These early experiences laid a crucial foundation for his artistic journey.

Academic Path and Parisian Exposure

Malczewski's formal artistic education began in 1872 when he moved to Krakow. There, he enrolled in the prestigious Academy of Fine Arts, studying under notable artists such as Władysław Łuszczkiewicz and Feliks Szynalewski. These initial years provided him with a solid grounding in academic technique and exposed him to the prevailing artistic currents in Poland.

A pivotal figure in his Krakow education was Jan Matejko, the leading Polish historical painter of the era. Matejko's monumental canvases, imbued with Romanticism and fervent nationalism, made a significant impact on Malczewski. While Malczewski would eventually diverge towards Symbolism, Matejko's emphasis on historical narrative and patriotic themes resonated deeply and left a lasting imprint on his approach to subject matter.

Seeking broader horizons, Malczewski traveled to Paris in 1876 to continue his studies. He worked in the studio of Henri Lehmann and attended the École des Beaux-Arts. This period was crucial for his development, exposing him to the vibrant Parisian art scene. While he would have encountered the works of Impressionists like Claude Monet and Édouard Manet, it was the burgeoning Symbolist movement that truly captured his interest, particularly the works of French masters such as Gustave Moreau and Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, whose explorations of myth, dream, and inner worlds aligned with his own burgeoning artistic sensibilities.

The Rise of a Symbolist Vision

Around 1890, Malczewski's art underwent a significant transformation, marking his definitive turn towards Symbolism. This shift moved him away from purely naturalistic or historical representations towards a more introspective and allegorical mode of expression. His works began to be populated by figures and scenes laden with multiple layers of meaning, drawing from a rich tapestry of sources including Polish history, folklore, Greek mythology, and Christian iconography.

This period saw the creation of some of his most iconic works, which established him as a leading voice in Polish Symbolism. He began exploring profound themes concerning the destiny of Poland, the struggles of its people under foreign occupation, the universal experiences of life and death, the role of the artist, and the very essence of artistic creation. His paintings became complex visual poems, inviting viewers to decipher their intricate symbolic language.

One of the defining characteristics of his Symbolist phase was the seamless integration of realistic detail with fantastical or allegorical elements. Figures from myth or folklore might appear in contemporary Polish settings, or familiar landscapes could be imbued with an otherworldly atmosphere. This blend created a unique tension and resonance, grounding his symbolic explorations in a tangible reality while simultaneously elevating them to the realm of universal ideas. Melancholia (1890-1894) is a prime example from this crucial period, embodying his newfound direction.

Key Themes and Motifs: National Identity and History

A central pillar of Malczewski's oeuvre is his engagement with Polish national identity and history. Living during a time when Poland was partitioned and absent from the map of Europe, his art became a powerful vehicle for expressing national aspirations, mourning past glories, and contemplating the nation's fate. He was closely associated with the patriotic "Young Poland" (Młoda Polska) movement, a cultural and artistic flourishing that sought to preserve and revitalize Polish culture in the face of oppression.

His series depicting Polish exiles deported to Siberia are among his most poignant works addressing national suffering. Paintings like the renowned Vicious Circle (Błędne koło, 1895-1897) vividly portray the hardship, despair, and flickering hope of those condemned to exile. The figures, often caught in cyclical, inescapable arrangements, symbolize the perceived powerlessness and the tragic destiny of the nation under foreign rule.

Later in his career, particularly after Poland regained independence in 1918, his works sometimes reflected a sense of national pride and hope, as seen in pieces like Imperial Crown. Throughout his life, however, his art consistently served as a mirror reflecting the complex emotional and historical landscape of Poland, grappling with its past, present, and uncertain future through a deeply symbolic lens.

Key Themes and Motifs: Life, Death, and the Human Condition

Beyond national concerns, Malczewski delved deeply into universal questions about human existence, particularly the themes of life, death, and fate. Influenced perhaps by personal losses and the turbulent history of his homeland, his work is permeated with a sense of melancholy and an awareness of mortality. Death, often personified, is a recurring figure in his paintings.

Melancholia (1890-1894) stands as a seminal work exploring psychological and existential angst. It depicts a swirling vortex of figures emerging from an artist's canvas, representing various aspects of Polish society and history, trapped in a cycle of struggle and despair. The painting is not merely an expression of sadness but a profound meditation on the burdens of history, the constraints of reality, and the human spirit's yearning for freedom.

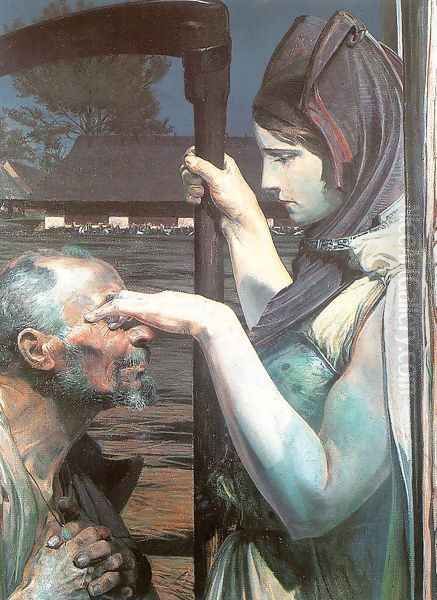

Another significant work exploring mortality is Thanatos (1898), where the figure of Death is presented not necessarily as terrifying, but as an inevitable, almost gentle presence. Malczewski often portrayed Death (personified as the Greek god Thanatos or as an angel) interacting with the living, blurring the boundary between the two realms. This recurring motif reflects his philosophical contemplation of life's fragility and the inescapable nature of destiny.

Key Themes and Motifs: Myth, Folklore, and the Bible

Malczewski possessed an extraordinary ability to weave together diverse narrative threads from mythology, folklore, and the Bible, creating rich, multi-layered allegories. He drew heavily on Greek mythology, populating his canvases with figures like fauns, chimeras, and mythological heroes, often placing them in distinctly Polish landscapes. Works like Bacchanalia explore classical themes of revelry and abandon, reinterpreted through his unique vision.

Polish folklore provided another vital source of inspiration. Elements from traditional legends, rural customs, and folk beliefs frequently appear in his paintings, grounding his symbolic narratives in the cultural soil of his homeland. This connection to folk tradition was integral to the Young Poland movement's emphasis on national roots.

Biblical stories and Christian symbolism also feature prominently. Malczewski often reinterpreted familiar religious narratives, infusing them with contemporary relevance or personal meaning. Figures like Christ, angels, and saints appear, but often in unconventional contexts, serving his broader symbolic explorations of suffering, redemption, art, and the human condition. This syncretic approach allowed him to create complex works that resonated on multiple levels.

Key Themes and Motifs: The Artist and His Muse

A fascinating aspect of Malczewski's work is his frequent exploration of the artist's role and the nature of artistic creation itself. He often included self-portraits in his paintings, sometimes depicting himself directly as the artist, other times casting himself in various allegorical roles – as a knight, a saint, or even interacting with mythological figures. These self-representations are often tinged with irony or self-deprecating humor.

The relationship between the artist and his inspiration, often personified as a muse, is another recurring theme. His long-term relationship with Maria Balowa significantly influenced this aspect of his work; she served not only as a model but also as an embodiment of his ideal feminine figure and artistic muse. Paintings like Painter's Muse (Natchnienie malarza, dated variously, with a key version around 1897) directly address the dynamic between creator and inspiration, exploring the sources of creativity, its challenges, and its transformative power.

Through these works, Malczewski reflected on his own identity as an artist, the burdens and privileges of his calling, and the complex interplay between life, art, and inspiration. His willingness to place himself within the symbolic narratives of his paintings adds a layer of personal intimacy and intellectual depth to his oeuvre.

Key Themes and Motifs: Nature and the Supernatural

Malczewski held a deep love for the Polish landscape, which features prominently in many of his paintings. However, his depiction of nature often transcends mere representation. Landscapes are frequently imbued with symbolic meaning or serve as backdrops for fantastical or mythological events. Hills, rivers, fields, and forests become stages for his allegorical dramas.

He masterfully blended detailed, naturalistic renderings of the Polish countryside with supernatural or dreamlike elements. Fauns might lounge in a recognizable Polish meadow, or angels might appear against the backdrop of a familiar village. This fusion of the real and the fantastical is a hallmark of his style, creating an atmosphere that is both grounded and otherworldly.

Works like At the Hill of Norbertine Monastery exemplify this approach, where a specific location is rendered with care but also infused with a sense of mystery and spiritual significance, possibly linking the natural world with religious or historical undertones. For Malczewski, nature was not just a setting but an active participant in the symbolic narratives he constructed, reflecting deeper truths about life, history, and the human spirit.

Artistic Style and Technique

Jacek Malczewski's artistic style is highly distinctive and instantly recognizable. While rooted in academic training, it evolved into a unique form of Symbolism characterized by several key features. His compositions often possess a monumental quality, even in smaller works, with figures rendered with solidity and presence. He favored strong, clear forms and often arranged figures in complex, dynamic, or cyclical patterns, as seen in Melancholia and Vicious Circle.

His use of color is particularly noteworthy. He could employ a rich, vibrant palette reminiscent of Romanticism, especially in depicting landscapes or certain mythological scenes. However, he also utilized more somber, earthy tones to convey melancholy, hardship, or the weight of history. His colors are often symbolic rather than purely naturalistic, contributing significantly to the mood and meaning of the work.

While primarily a Symbolist, elements of other styles can be discerned in his work. His early paintings show influences of Naturalism and Realism in their detailed observation. There are also touches of Neo-Rococo elegance in his treatment of certain figures, particularly female ones, and in decorative details. However, all these elements were ultimately subsumed into his overarching Symbolist vision, creating a style that was both eclectic and highly personal. His technique involved careful drawing and modeling, combined with a painterly application that gave texture and life to his surfaces.

Connections and Contemporaries

Malczewski was an active participant in the artistic life of his time, both in Poland and internationally. In Krakow, he was a central figure within the Young Poland movement, interacting with other leading artists and writers who shared a commitment to Polish culture. He was a member of the "Sztuka" (Art) Society of Polish Artists, a group dedicated to promoting high standards and exhibiting Polish art. His contemporaries within this vibrant milieu included fellow painters like Stanisław Wyspiański, Józef Mehoffer, Leon Wyczółkowski, and Olga Boznańska.

His education brought him into contact with influential teachers like Władysław Łuszczkiewicz, Feliks Szynalewski, and the dominant Jan Matejko in Krakow, and Henri Lehmann in Paris. His travels and studies exposed him to broader European trends. His participation in an archaeological expedition organized by Count Karol Lanckoroński broadened his horizons further. His personal life included significant relationships, notably with his muse Maria Balowa, and connections through his family, such as his father Julian's association with the patriot Adolf Dygasiński, and his own relationship with his writer uncle Feliks Karczewski. He also knew the writer Józef Brandys during his academy years.

Internationally, Malczewski's stature was recognized through his membership in the prestigious Vienna Secession, connecting him with leading figures of Austrian Art Nouveau. His work has often been compared to other European Symbolists, such as the French Gustave Moreau and the Swiss Arnold Böcklin, highlighting his place within the broader European Symbolist movement. While stylistically different, comparisons have even been drawn to the later Surrealist Salvador Dalí, perhaps due to the dreamlike and psychologically charged nature of some of his imagery.

Teaching and Legacy

Beyond his prolific output as a painter, Jacek Malczewski made significant contributions as an educator. He served as a professor at the Krakow Academy of Fine Arts from 1896 to 1900 and again from 1912 to 1921 (the provided text mentions 1901-1912, sources vary slightly on exact dates but confirm his long tenure). His influence extended further when he was appointed Rector of the Academy in 1912, a position reflecting his esteemed status in the Polish art world.

As a teacher, he inspired and mentored numerous students, shaping the next generation of Polish artists. His emphasis on technical skill combined with profound thematic content left a lasting mark on the Academy's curriculum and ethos. He encouraged his students to find their own voices while remaining connected to Polish traditions and contemporary European currents.

In his later years, Malczewski's eyesight began to fail, a cruel blow for a visual artist, but he continued to work as much as possible. He passed away in Krakow in 1929 and was buried in the Crypt of the Meritorious at Skałka, a national pantheon reserved for Poland's most distinguished cultural figures – a testament to his immense contribution. His legacy was further secured by his son, Rafał Malczewski, also a notable painter, who ensured his father's works were preserved, notably through donations to national museums. Today, Jacek Malczewski is revered as a cornerstone of Polish modern art, his works cherished for their artistic brilliance and profound exploration of the Polish soul.

Conclusion

Jacek Malczewski's art offers a profound and multifaceted journey into the heart of Polish Symbolism. His paintings are complex tapestries woven from threads of national history, personal experience, universal myths, and deep philosophical inquiry. From the suffering of Siberian exiles in Vicious Circle to the existential depths of Melancholia and the introspective Painter's Muse, his work consistently engages with the most significant themes of his time and the enduring questions of human existence.

His unique style, blending realistic detail with fantastical imagery, and his mastery of color and composition created a visual language that was entirely his own yet resonated deeply within the context of European Symbolism. As a painter, patriot, teacher, and visionary, Malczewski not only defined an era in Polish art but also created a body of work that continues to captivate and intrigue viewers with its beauty, complexity, and emotional power. He remains, unequivocally, the father of Polish Symbolism and one of Poland's most important artistic figures.