Karl Mediz stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in Austrian art at the turn of the 20th century. His life and work offer a fascinating window into the confluence of Symbolism, Naturalism, and the burgeoning modern art movements in Central Europe. A painter of evocative landscapes, haunting portraits, and mystical allegories, Mediz, alongside his equally talented wife Emilie Mediz-Pelikan, carved a unique niche in an era dominated by luminaries like Gustav Klimt. His story is one of artistic dedication, personal tragedy, and posthumous rediscovery, reflecting the turbulent cultural and political currents of his time.

Early Life and Formative Influences

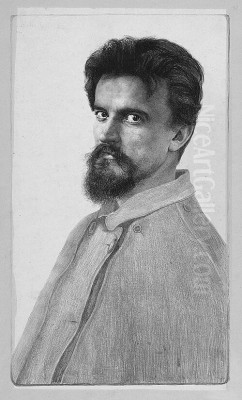

Karl Mediz was born on June 4, 1868, in Vienna, Austrian Empire (though some sources mention Heroldsheim, he grew up in Retz, Austria). His early artistic inclinations led him to Vienna, the vibrant cultural heart of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Here, he embarked on his formal artistic training, initially studying at the prestigious Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna. Among his early instructors was the history painter Christian Griepenkerl, a traditionalist known for his large-scale allegorical works. Griepenkerl's academic approach would have provided Mediz with a solid foundation in drawing and composition, even if Mediz's own artistic path would eventually diverge significantly.

Another influential teacher during his Viennese period was Fritz L’Allamand, a painter recognized for his military scenes and genre paintings. L’Allamand’s emphasis on realistic depiction and narrative clarity likely contributed to Mediz's later skill in detailed rendering, a characteristic that would become a hallmark of his mature style, even when applied to fantastical subjects. These early years in Vienna exposed Mediz to the rich artistic heritage of the city, but also to the simmering tensions between established academic traditions and emerging avant-garde movements.

Munich and Paris: Broadening Horizons

Seeking to further refine his skills and explore different artistic currents, Mediz moved to Munich. The Bavarian capital was another major art center, known for its own dynamic art scene and influential academies. In Munich, he continued his studies, working under artists such as Paul Hermann Wagner and Alexander Demetrius Goltz. Wagner was associated with the Munich Secession, a progressive group of artists, and his influence might have steered Mediz towards more modern modes of expression. Goltz, also active in both Munich and Vienna, was a versatile artist whose work spanned portraiture and landscape, offering Mediz exposure to varied genres.

The allure of Paris, then the undisputed capital of the art world, drew Mediz, like so many artists of his generation. He enrolled at the Académie Julian, a renowned private art school that attracted students from across the globe. At the Académie Julian, he had the opportunity to study under William-Adolphe Bouguereau and Tony Robert-Fleury. Bouguereau was a towering figure of French academic art, celebrated for his meticulously finished mythological and allegorical paintings. While Mediz would not fully embrace Bouguereau's polished classicism, the emphasis on anatomical precision and refined technique undoubtedly left an impression. Robert-Fleury, also a respected academic painter, further solidified Mediz's technical grounding. His time in Paris exposed him to Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, and the nascent Symbolist movement, which would prove particularly influential.

The Symbolist Path and Emilie Mediz-Pelikan

A pivotal moment in Karl Mediz's life and artistic development was his meeting and subsequent marriage in 1891 to the painter Emilie Pelikan. Emilie Mediz-Pelikan (1861-1908) was a formidable artist in her own right, known for her powerful, often melancholic, landscapes and floral still lifes imbued with a strong Symbolist sensibility. Their artistic partnership was profound, a true union of creative spirits. They shared a deep connection to nature and a penchant for exploring its mystical and symbolic dimensions.

Together, Karl and Emilie navigated the challenges of an artistic career, often facing financial hardship. They spent time in the artists' colony of Dachau, near Munich, a place known for its plein-air painters and its focus on landscape. Later, they lived in Krems an der Donau in Austria, where the dramatic landscapes of the Wachau Valley provided ample inspiration. Their shared artistic journey saw them both gravitate towards Symbolism, a movement that sought to express ideas, emotions, and spiritual truths through suggestive imagery, rather than direct representation. Artists like Arnold Böcklin, with his moody, mythological landscapes, or Fernand Khnopff, with his enigmatic figures, were key European proponents of this style, and their influence can be felt in the broader Symbolist milieu that Mediz inhabited.

Karl Mediz's Symbolism often manifested in his depiction of fantastical creatures, mythological scenes, and landscapes imbued with an otherworldly atmosphere. He was less concerned with the overt, decorative Symbolism of some of his Viennese contemporaries, like Gustav Klimt during his "Golden Phase," and more aligned with a darker, more introspective strand of the movement, akin to the work of artists like Alfred Kubin or Rudolf Jettmar, who also explored themes of the subconscious, dreams, and the uncanny.

Representative Works and Stylistic Hallmarks

Karl Mediz's oeuvre is characterized by a unique fusion of meticulous Naturalism in detail and a profound Symbolist spirit in overall conception. He possessed a remarkable ability to render textures, light, and natural forms with almost photographic precision, yet he employed this skill to create scenes that transcended mere reality.

One of his most celebrated works is The Birch Forest (Ein Birkenwald), painted around 1894. This large-scale canvas depicts a dense forest scene, possibly inspired by Greek mythology, populated by fantastical beings. The rendering of the birch trees, the play of light filtering through the leaves, and the intricate detail of the forest floor are executed with astonishing naturalistic skill. However, the presence of mythical figures and the overall enigmatic atmosphere firmly place the work within the Symbolist tradition. It is a prime example of what the critic Ludwig Hevesi, a significant voice in Viennese art criticism, termed "New German Idealism," a style that sought to combine realistic depiction with profound, often spiritual or mythological, content. Hevesi recognized Mediz as a leading figure in this tendency.

Another key work, Dragon on a Rocky Shore (Drache an felsiger Küste), dating from 1891, showcases Mediz's fascination with the fantastical. The painting features a meticulously rendered, albeit wingless, dragon perched on a rugged, sun-drenched coastline. The depiction of the rocks, the sea, and the quality of light is strikingly realistic, creating a powerful contrast with the mythical subject. Contemporaneous critics sometimes found such works "bizarre" or "very peculiar," highlighting the unconventional nature of Mediz's vision, which did not always align with prevailing tastes but demonstrated his commitment to a personal artistic language.

His portraits, too, often carried a psychological depth and a hint of the uncanny. He painted his wife, Emilie, numerous times, capturing her intense artistic personality. Works like Forest Fairy (Waldfee) or Red Angel (Roter Engel) further exemplify his exploration of mythological and allegorical themes, often characterized by strong color contrasts and a palpable sense of mystery. The Red Angel, for instance, uses vibrant, almost unsettling color to convey a sense of passion and otherworldly power. His attention to detail extended to every element, from the gnarled bark of trees to the subtle expressions of his figures, creating a world that was both believable in its components and dreamlike in its entirety.

Involvement with Artistic Groups: Hagenbund

Karl Mediz was an active participant in the Viennese art scene and was associated with important progressive art groups. He became a member of the Hagenbund, an artists' association founded in Vienna in 1900. The Hagenbund emerged as an alternative to the more established Association of Austrian Artists (Künstlerhaus) and, to some extent, even the Vienna Secession, which by then had its own internal dynamics. The Hagenbund aimed to promote modern art and provide a platform for artists who felt excluded from the more conservative institutions.

The Hagenbund was known for its diverse membership, encompassing a range of styles from late Impressionism and Art Nouveau to early Expressionism. It played a crucial role in introducing international modern art to Vienna, organizing exhibitions that featured works by artists from across Europe. Mediz's involvement with the Hagenbund placed him firmly within the modernist camp, alongside artists who were pushing the boundaries of artistic expression. His works were exhibited in Hagenbund shows, where they were often praised for their power and beauty, even if their unique blend of naturalism and fantasy set them apart. While he also participated in activities related to the Vienna Secession, his primary group affiliation seems to have been with the Hagenbund, which better accommodated his individualistic style.

The artistic climate in Vienna at this time was incredibly fertile, with figures like Gustav Klimt, Egon Schiele, and Oskar Kokoschka revolutionizing Austrian art. While Mediz's style differed significantly from the more overtly modernist or expressionist tendencies of these artists, he shared their desire to break from academic constraints and explore new forms of artistic truth. His Symbolism, while distinct, contributed to the rich tapestry of Viennese modernism.

The Profound Partnership with Emilie Mediz-Pelikan

The artistic and personal relationship between Karl Mediz and Emilie Mediz-Pelikan cannot be overstated. They were not just husband and wife but true artistic partners, influencing and supporting each other's work. Emilie was a highly accomplished painter, whose powerful landscapes and floral studies often possessed a raw, elemental quality. Her approach to Symbolism was perhaps more directly tied to the emotional resonance of nature itself, while Karl often incorporated more explicit mythological or narrative elements.

They shared a studio, critiqued each other's work, and exhibited together. Their financial struggles in the early years of their marriage forged a strong bond, and their shared dedication to their art was unwavering. Emilie's focus on the expressive power of color and her ability to imbue natural scenes with deep emotional content likely resonated with Karl and may have encouraged his own explorations of mood and atmosphere. Similarly, Karl's technical mastery and his interest in complex allegorical compositions may have provided a counterpoint to Emilie's more direct engagement with landscape.

Their daughter, Gertrude Honzatko-Mediz, also became an artist, continuing the family's artistic legacy, particularly in the realm of what might be termed supernatural or fantastical art. This suggests a household where art was not just a profession but a way of life, a shared passion passed down through generations. The creative synergy between Karl and Emilie was a defining feature of their careers, and their joint exhibitions highlighted the complementary nature of their distinct yet related artistic visions.

Later Years, Tragedy, and Obscurity

The early 20th century brought both artistic recognition and profound personal tragedy for Karl Mediz. The death of his beloved wife, Emilie, in March 1908, at the young age of 46, was a devastating blow. Emilie had been suffering from heart problems, and her passing left Karl bereft. He was deeply affected by this loss, and it marked a turning point in his life and career.

After Emilie's death, Karl Mediz largely withdrew from public life and the bustling Viennese art scene. He continued to paint, but his output became more sporadic, and he ceased to exhibit regularly. The vibrant artistic energy that had characterized his earlier years, fueled in part by his partnership with Emilie, seemed to diminish. He moved to Dresden, Germany, in his later years, living a more reclusive existence.

The political upheavals of the first half of the 20th century, including two World Wars, further contributed to his descent into obscurity. Much of his and Emilie's artistic estate, which he had carefully preserved, faced a precarious fate. Following World War II and the division of Germany, a significant portion of their works, located in Dresden, fell under the control of the East German communist regime. These works were confiscated and effectively hidden from public view for decades.

Karl Mediz himself passed away in Dresden on January 11, 1945, just months before the end of World War II. He died largely forgotten by the art world that had once acknowledged his unique talent. The changing tastes in art, the rise of abstraction, and the horrors of war had overshadowed the contributions of many artists of his generation, particularly those whose work did not fit neatly into the dominant narratives of modernism.

Posthumous Rediscovery and Legacy

For many years after his death, Karl Mediz and Emilie Mediz-Pelikan remained relatively obscure figures, their works known primarily to a small circle of connoisseurs and art historians. The Cold War and the Iron Curtain further complicated access to and research on their oeuvres, particularly the works held in East Germany.

A significant step towards their rediscovery occurred in 1975, when the confiscated artworks were transferred from Dresden to the Hermann-Gebhard-Museum in Graz, Austria. However, it was not until 1986, with a major retrospective exhibition, that their art began to receive wider public and critical attention. This exhibition, and subsequent research and publications, helped to re-evaluate their contributions to Austrian art at the turn of the century.

Today, Karl Mediz is recognized as an important representative of Austrian Symbolism, an artist who skillfully blended meticulous naturalistic technique with a profound sense of mystery and fantasy. His ability to create believable yet otherworldly scenes, his exploration of mythological themes, and his deep connection to the natural world mark him as a distinctive voice. His work, alongside that of Emilie Mediz-Pelikan, offers a crucial counterpoint to the more famous iterations of Viennese modernism, revealing the diversity and complexity of artistic production during this dynamic period.

His paintings can be found in several Austrian museums, including the Belvedere in Vienna and the Neue Galerie Graz, as well as in private collections. Art historians now appreciate the unique synthesis he achieved between the precise observation of nature, reminiscent of earlier masters like Albrecht Dürer in his detailed studies, and the imaginative, dreamlike qualities championed by Symbolist painters such as Gustave Moreau or Odilon Redon. While perhaps not as revolutionary as some of his contemporaries, Mediz's dedication to his personal vision and his technical brilliance ensure his enduring place in the history of Austrian art. His life story, marked by early promise, profound partnership, tragic loss, and eventual rediscovery, serves as a poignant reminder of the often-unpredictable fortunes of artists and their legacies.