Edwin Willard Deming stands as a significant figure in American art history, an artist whose life and work were profoundly dedicated to documenting the cultures and lives of Native American peoples during a period of immense transition. Born in the mid-19th century, Deming witnessed the fading era of the independent Native American nations and devoted his considerable talents as a painter, sculptor, and illustrator to capturing their traditions, spirituality, and daily existence with empathy and remarkable detail. His extensive travels, deep immersion in various tribal communities, and formal artistic training combined to create a body of work that serves not only as fine art but also as a valuable historical and ethnographic record.

Deming's unique perspective, shaped by childhood experiences and later sustained engagement, allowed him to portray his subjects with an intimacy and understanding that set him apart from many contemporaries. While others depicted the West through lenses of conflict or romanticized nostalgia, Deming often focused on the dignity, resilience, and rich inner lives of the people he came to know and respect. His legacy endures in major museum collections and continues to offer insight into the diverse cultures of North America's indigenous populations.

Early Life and Formative Encounters

Edwin Willard Deming was born in Ashland, Ohio, on August 26, 1860. His formative years, however, were spent far from the forests of Ohio. While he was still a child, his family relocated to the prairie region of western Illinois. This move proved pivotal for the future artist. Their new home placed them in proximity to the Winnebago (Ho-Chunk) people, and young Deming spent considerable time playing with Winnebago children. These early, unmediated interactions fostered a deep-seated curiosity and respect for Native American culture that would define his artistic path.

Unlike many artists who approached Native subjects as outsiders later in life, Deming's connection was rooted in his youth. This early familiarity likely provided him with a foundation of understanding and empathy that informed his later, more intensive studies and travels. It instilled in him a sense of shared humanity and perhaps a recognition of the cultural richness that was often overlooked or misrepresented in mainstream American society at the time. This period was crucial in shaping his worldview and artistic inclinations, steering him away from conventional subjects and towards the path he would ultimately pursue.

His parents reportedly hoped he would pursue a more conventional career in business or law. However, the pull towards art, likely fueled by his experiences and innate talent, was strong. Deming initially embarked on a path of self-instruction, honing his observational skills and developing a passion for visual representation. This independent spirit would characterize much of his career, even as he later sought formal training.

Formal Artistic Training: New York and Paris

Recognizing the need for formal instruction to refine his skills, Deming made his way to New York City. In 1883, he enrolled at the prestigious Art Students League, a hub for aspiring artists seeking training outside the more rigid confines of the National Academy of Design. The League offered a liberal environment where students could study with prominent American artists, focusing on life drawing and composition. This period provided Deming with essential technical grounding and exposed him to the vibrant New York art scene.

Seeking further refinement and exposure to European traditions, Deming traveled to Paris, the undisputed center of the art world in the late 19th century. From 1884 to 1885, he studied at the Académie Julian, a renowned private art school that attracted students from across the globe, including many Americans. There, he received instruction from respected academic painters Gustave Boulanger and Jules Lefebvre. Both were masters of the human figure and proponents of the rigorous draftsmanship and polished finish characteristic of French academic art.

This European training was invaluable. It equipped Deming with a sophisticated understanding of anatomy, composition, and technique. However, unlike some American artists who fully adopted European styles and subjects upon their return, Deming integrated this academic foundation with his pre-existing passion. His Paris education provided him with the technical mastery needed to effectively translate his unique observations and deep understanding of Native American life onto canvas and into bronze.

Dedication to Native American Subjects

Upon returning to the United States, Deming made a conscious decision to dedicate his artistic career primarily to depicting Native American life. This was not merely a choice of subject matter; it was a commitment born from his early experiences and a desire to create an authentic record. He embarked on extensive travels throughout the American West, seeking out and living among various tribes to gain firsthand knowledge of their cultures, customs, and environments.

His journeys took him to numerous regions and brought him into contact with diverse groups, including the Blackfeet and Crow (Apsáalooke) of the Northern Plains, the Sioux (Lakota, Dakota, Nakota), and various Pueblo peoples of Arizona and New Mexico, such as the Zuni and Hopi, as well as Apache groups. He didn't just observe; he immersed himself. A particularly significant period occurred in 1889 when he lived near the Little Bighorn River in Montana, spending considerable time with the Crow people. This deep immersion allowed him to witness ceremonies, learn about social structures, and understand their relationship with the land and wildlife in a way that brief visits could not achieve.

Sources suggest Deming spent a cumulative total of over thirty years living intermittently with different Native American communities throughout his adult life. This sustained engagement was fundamental to his work's authenticity. He learned languages, participated in daily activities, and gained the trust of many individuals, allowing him access to aspects of life often hidden from outsiders. This dedication distinguished him from artists who relied on studio models or fleeting encounters, lending his work a palpable sense of lived experience.

Artistic Philosophy and Approach

Deming's approach to his chosen subject matter was driven by a profound respect and a sense of responsibility. He perceived the rapid changes encroaching upon traditional Native American ways of life – the expansion of settlements, the impact of government policies, the decline of the buffalo – and felt compelled to document these cultures before they were irrevocably altered. Some accounts suggest he viewed his art partly as a way to "atone" for the destructive impact of westward expansion on Native cultures, a sentiment reflecting a deeper ethical engagement with his subjects.

He aimed for accuracy not just in visual details – clothing, dwellings, artifacts – but also in capturing the spirit and dignity of the people. He sought to portray Native Americans not as stereotypes or exotic curiosities, but as complex individuals with rich cultural and spiritual lives. His work often emphasizes themes of harmony with nature, reverence for wildlife, and the importance of ceremony and tradition.

While striving for authenticity, Deming was also an artist, not strictly an ethnographer. He combined his direct observations with his artistic sensibilities, employing composition, color, and light to create compelling and emotionally resonant images. He navigated the line between documentation and interpretation, aiming to convey the essence of his subjects' experiences as he understood them. His long-term relationships likely allowed for a collaborative element, where his depictions were informed by the perspectives of the people themselves, though the final artistic interpretation remained his own.

Painting: Style and Subjects

Deming's painting style reflects a blend of his academic training and his direct engagement with his subjects and their environments. His grounding in figure drawing is evident in the anatomical accuracy of both humans and animals. However, his work often transcends strict academic realism, incorporating elements associated with Impressionism, particularly in his handling of light and atmosphere. He frequently employed a softer focus and visible brushwork, lending a sense of immediacy and vibrancy to his scenes.

His palette could range from the subtle, earthy tones of the plains and deserts to moments of vibrant color, especially when depicting ceremonial attire or dramatic natural phenomena like sunsets. He was adept at capturing the unique quality of light in the American West – the clear, bright sunlight of midday, the warm glow of dawn and dusk, the ethereal light of a moonlit night. This sensitivity to light and atmosphere contributes significantly to the mood and emotional impact of his paintings.

His subjects were diverse, encompassing many facets of Native American life. He painted scenes of daily activities – hunting, fishing, setting up camp, tending horses. He depicted important ceremonies and spiritual practices, often conveying a sense of reverence and mystery. Portraits captured the individuality and dignity of his subjects. He also frequently explored the deep connection between Native peoples and the animal world, showing riders and horses moving as one, hunters tracking game with intimate knowledge, or figures communing with wildlife in scenes imbued with mythological or spiritual significance.

Major Painted Works

Several paintings stand out as representative of Deming's oeuvre and artistic concerns. `Indian Orpheus`, held by the Smithsonian American Art Museum, is one of his most recognized works. It depicts a lone Native American figure playing a flute, charming the surrounding wildlife – deer, bears, rabbits – who listen attentively. The scene evokes classical mythology but recasts it within a Native American context, highlighting the theme of harmony between humans and nature, and perhaps suggesting the power of music and spirituality. The use of color and light creates a mystical, almost dreamlike atmosphere.

His time with the Crow people resulted in numerous works capturing their life on the Northern Plains. Paintings depicting Crow encampments, horse culture, and scenes related to their specific traditions showcase his detailed observation. For example, works titled along the lines of `Crow Camp Scene` or `Life on the Plains - Crow Tribe` (precise titles vary) often feature tipis against expansive landscapes, figures engaged in daily tasks, and the ubiquitous presence of horses, central to Plains culture. These works demonstrate his ability to render both the specifics of cultural artifacts and the vastness of the Western environment.

Deming also created significant mural works. He was commissioned to paint murals for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, focusing on Native American themes. These large-scale works allowed him to depict complex scenes and narratives for a broad public audience, further solidifying his reputation as a leading interpreter of Native American life. While specific details of all murals might require further research, their presence in such a prominent institution underscores the perceived importance and quality of his work during his lifetime.

Another notable painting, sometimes titled `The Vision` or similar, might depict a spiritual seeker or a moment of shamanic insight, reflecting Deming's interest in the religious and mystical aspects of the cultures he studied. These works often possess a heightened emotional intensity and symbolic depth. `Indian Encampment`, mentioned as a watercolor and pencil work, exemplifies his skill across different media and his consistent focus on communal life.

Sculptural Works

Beyond painting, Edwin Deming was also a talented sculptor, translating his understanding of form and anatomy into three dimensions, primarily working in bronze. His sculptures often focused on similar themes as his paintings: Native American figures, wildlife, and dramatic interactions within the natural world. His academic training provided a strong foundation for modeling the human and animal form with accuracy and dynamism.

One of his well-known sculptures is `The Fight` (c. 1906). This dynamic bronze depicts a dramatic struggle between a grizzly bear and a mountain lion (sometimes described as a panther or puma). It showcases Deming's ability to capture intense action and raw animal power. The composition is taut, conveying the ferocity of the encounter. Works like this placed him alongside other sculptors of Western wildlife, such as Alexander Phimister Proctor.

In contrast to the intensity of `The Fight`, Deming also displayed a sense of humor and charm in his sculpture. `Mutual Surprise` (c. 1907) exemplifies this. The small bronze depicts a bear cub encountering a turtle, capturing a moment of comical astonishment and curiosity between two very different creatures. The juxtaposition of the fuzzy, startled cub and the stolid turtle reveals Deming's keen observation of animal behavior and his ability to infuse his work with personality.

His sculptural subjects also included Native American figures, sometimes on horseback, echoing the equestrian themes popular among Western artists like Frederic Remington and Charles M. Russell. These bronzes allowed him to explore the relationship between rider and horse in three dimensions, emphasizing movement and cultural identity. Deming's sculptures, like his paintings, contributed significantly to the visual representation of the American West and its inhabitants.

Illustrations and Collaborations

Deming's talents extended to illustration, a field experiencing a "Golden Age" during his active years. He contributed illustrations to prominent publications, most notably `Outing Magazine`, a popular periodical focused on outdoor life, sport, and travel. His illustrations often accompanied articles about the American West, exploration, and Native American life, bringing these subjects to a wide readership. His ability to accurately depict cultural details and create engaging scenes made him a valuable contributor.

The provided information mentions a collaboration with the famous Western artist and illustrator Frederic Remington for Outing Magazine, depicting Cedar (likely referring to a specific group or region) and Crow life. While both artists frequently illustrated Western and Native themes for similar publications, the exact nature of direct "collaboration" on specific pieces versus contemporary contribution warrants careful consideration. They were certainly key figures defining the visual image of the West for the American public through illustration. Deming's work, like Remington's, helped shape popular perceptions, though Deming often brought a more intimate, less conflict-focused perspective gained from his long-term immersion.

Deming also collaborated with his wife, Therese Osterheld Deming, on a series of children's books focused on Native American life. Titles like "Little Indian Folk" and "American Animal Life" combined his illustrations with texts (likely written or co-written by Therese) designed to educate young readers about Native cultures and North American wildlife in an accessible and respectful manner. This endeavor further highlights his commitment to sharing his knowledge and fostering understanding across generations. His illustrative work, therefore, played a crucial role in disseminating images and narratives about Native Americans and the West.

Connections and Contemporaries: The Western Art Scene

Edwin Deming worked during a vibrant period for American art, particularly for artists focused on the American West. He was a contemporary of, and interacted with, many key figures who were also shaping the artistic representation of this region and its peoples. Understanding his place within this network provides valuable context.

Frederic Remington (1861-1909) and Charles M. Russell (1864-1926) are perhaps the most famous names associated with Western art of this era. Like Deming, they were painters, sculptors, and illustrators deeply invested in depicting cowboys, Native Americans, soldiers, and wildlife. While Remington often focused on action, conflict, and the perceived drama of the "vanishing" West, and Russell became known for his narrative scenes and deep connection to the cowboy life of Montana, Deming's work often carried a quieter, more ethnographic and spiritual tone, reflecting his different mode of engagement. All three, however, contributed immensely to the iconography of the West.

Deming also knew sculptors like James Earle Fraser (1876-1953), famous for the iconic End of the Trail sculpture and the design of the Buffalo Nickel, and Daniel Chester French (1850-1931), renowned for the Lincoln statue at the Lincoln Memorial. The provided text notes Deming discussed Native American culture with them, suggesting a shared interest among these artists in representing American themes, including its indigenous heritage, albeit through different artistic forms and sometimes different interpretations. Fraser, in particular, shared Deming's focus on Native American subjects. Other prominent sculptors of the era included Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1848-1907), whose influence shaped American sculpture.

Connections and Contemporaries: Taos and Beyond

While Deming traveled widely, his focus often differed geographically from the artists who coalesced in New Mexico, forming the Taos Society of Artists. Founded in 1915, key members like Joseph Henry Sharp (1859-1953), E. Irving Couse (1866-1936), Oscar E. Berninghaus (1874-1952), Ernest L. Blumenschein (1874-1960), Bert Geer Phillips (1868-1956), and W. Herbert Dunton (1878-1936) primarily depicted the Pueblo peoples of the Southwest. While Deming also painted Southwestern subjects, his extensive work with Plains tribes like the Crow and Blackfeet distinguished his focus. Nonetheless, he shared with the Taos artists a commitment to portraying Native American life with seriousness and artistic skill during the same general period. Later Taos members included Walter Ufer (1876-1936) and Victor Higgins (1884-1949).

Other contemporaries also engaged with Native American subjects. George de Forest Brush (1855-1941) painted Native Americans earlier than Deming, sometimes in a more idealized, neoclassical style, but shared an interest in the subject. The great landscape painters of the previous generation, such as Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902) and Thomas Moran (1837-1926), had established the grandeur of the Western landscape in the American imagination, setting a stage upon which artists like Deming focused more closely on the human inhabitants. The field of illustration included giants like Howard Pyle (1853-1911), whose influence extended to many artists depicting historical and American themes. Deming operated within this rich and varied artistic landscape, contributing his unique perspective.

Themes, Legacy, and Recognition

The overarching theme in Edwin Deming's work is the respectful and detailed portrayal of Native American life and culture during a critical period of change. His art explores the daily rhythms, spiritual beliefs, social structures, and deep connection to the natural world that characterized the lives of the peoples he knew. He sought to preserve a visual record of traditions he saw as potentially fading, driven by a genuine admiration and understanding cultivated over decades.

His legacy lies in this substantial body of work – paintings, sculptures, and illustrations – that offers a valuable window into late 19th and early 20th-century Native American life, particularly among Plains and Southwestern tribes. While viewed through the lens of his time, his work generally avoids the more egregious stereotypes common then, striving instead for accuracy and dignity. Art historians and ethnographers alike find value in his detailed renderings of clothing, ceremonies, and material culture. He is considered one of the first non-Native artists to dedicate such a significant portion of his career to living among and depicting Native Americans with such depth.

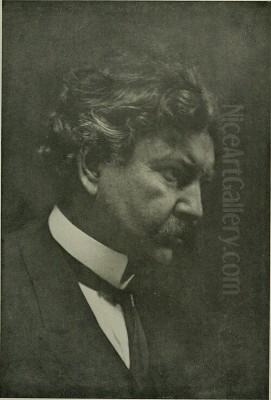

Deming achieved considerable recognition during his lifetime. His work was exhibited widely and acquired by major institutions, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington D.C., the American Museum of Natural History, the Whitney Museum of American Art, and the Brooklyn Museum. His patrons included prominent figures like President Theodore Roosevelt, himself deeply interested in the American West. The claim that he was the first artist whose photograph appeared on a U.S. postage stamp is a significant marker of his public stature, though verification of "first" status can be complex. Regardless, his inclusion indicates his national prominence.

Conclusion: An Enduring Contribution

Edwin Willard Deming passed away in New York City in 1942, leaving behind a rich artistic legacy. He was more than just a painter of the West; he was a dedicated chronicler, an artist who used his skills, honed through rigorous training and tireless observation, to document and honor the Native American cultures he deeply respected. His childhood encounters blossomed into a lifelong commitment, leading him across the continent to live with and learn from diverse indigenous nations.

His paintings capture the light, atmosphere, and daily life of the West with sensitivity. His sculptures convey dynamism and character, whether depicting wildlife or human figures. His illustrations brought scenes of Native life to a broad audience. Through all these mediums, Deming offered a perspective grounded in firsthand experience and genuine empathy, distinguishing his work within the broader field of Western American art.

Today, Edwin Willard Deming is remembered as a key figure among artists who depicted Native American subjects. His work continues to be studied for its artistic merit, its historical insights, and its representation of cultures undergoing profound transformation. He remains an important artist for understanding both the history of American art and the complex history of interactions between Euro-Americans and the indigenous peoples of North America. His dedication ensures that his vision of Native American life endures.