Károly Kernstok (1873-1940) stands as a monumental figure in the landscape of Hungarian art, a painter whose career navigated the turbulent currents of early 20th-century European modernism. His work, characterized by a dynamic synthesis of influences and a profound intellectual engagement with the nature of art, not only defined a crucial period in his nation's artistic development but also resonated with broader avant-garde movements across the continent. From his foundational role in radical art groups to his distinctive stylistic evolution, Kernstok's legacy is one of innovation, intellectual rigor, and an unwavering commitment to the transformative power of art.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born in Budapest in 1873, Károly Kernstok's artistic journey began with formal training in his home city before he, like many aspiring artists of his generation, sought the vibrant artistic milieus of Munich and, most significantly, Paris. The French capital, at the turn of the century, was a crucible of artistic revolution. It was here, studying at the Académie Julian, that Kernstok encountered the groundbreaking works of artists who were redefining the very language of painting.

The influence of French Post-Impressionism, particularly the structural concerns of Paul Cézanne and the expressive color of Henri Matisse, proved transformative for Kernstok. Cézanne's methodical deconstruction of reality into underlying geometric forms and his emphasis on the painted surface as a constructed reality offered a powerful alternative to academic naturalism. Matisse and the Fauves, with their audacious use of non-naturalistic color to convey emotion and create decorative harmony, further liberated Kernstok's palette and compositional approach. These encounters in Paris were pivotal, steering him away from the prevailing naturalistic tendencies of Hungarian art at the time.

The Formation of "The Eight" (Nyolcak)

Upon his return to Hungary, Kernstok became a leading voice for modern artistic principles. He was a central figure in the intellectual ferment that sought to break from the more conservative, naturalistic traditions, particularly those associated with the Nagybánya artists' colony. While the Nagybánya school, led by figures like Simon Hollósy and Károly Ferenczy, had itself been a progressive force introducing plein-air painting and Impressionistic tendencies to Hungary, by the early 1900s, a younger generation, including Kernstok, felt the need for a more radical departure.

This desire for a new artistic direction culminated in the formation of "The Eight" (Nyolcak) in 1909. Kernstok was not just a member but a key ideologue and founder of این group, which also included Róbert Berény, Dezső Czigány, Béla Czóbel, Ödön Márffy, Dezső Orbán, Bertalan Pór, and Lajos Tihanyi. "The Eight" are often considered Hungary's first truly avant-garde movement, championing principles of expressiveness, structural integrity, and a subjective interpretation of reality, directly influenced by French Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, and the burgeoning Cubist movement. Their exhibitions, starting with "New Pictures" in 1909, were landmark events, challenging established tastes and advocating for an art that was intellectually engaged and formally innovative.

Artistic Philosophy: Rationalism and the Essence of Form

Kernstok's art was deeply underpinned by a coherent philosophical framework. He was a leader of the "Neos," a faction within the broader avant-garde that, in contrast to the lingering naturalism of some contemporaries, advocated for a rational, selective approach to nature. He believed that art should not merely imitate the visible world but should seek to express its underlying essence and order through a conscious, intellectual process of formal construction.

His thinking was influenced by contemporary philosophers and art theorists, notably the German sculptor and theorist Adolf von Hildebrand, whose work "The Problem of Form in Painting and Sculpture" emphasized the importance of architectonic structure and clear spatial representation in art. Kernstok also engaged with the ideas of the young György Lukács, who was then developing his early aesthetic theories. For Kernstok, art was a means of restructuring perception and, by extension, had a role in the conceptual restructuring of society. He emphasized the "essence of form" and the transformative potential of art for both the individual and the collective. This intellectual rigor distinguished his approach and lent a powerful coherence to his artistic output.

Stylistic Evolution and Dominant Themes

Kernstok's stylistic journey was one of continuous evolution. His early works showed an adeptness in realistic portrayal, but his Parisian experiences catalyzed a shift towards a more modern idiom. He moved through a phase influenced by Post-Impressionism, characterized by stronger colors and more defined forms, before arriving at a style that was uniquely his own – a powerful blend of expressive force and structural clarity.

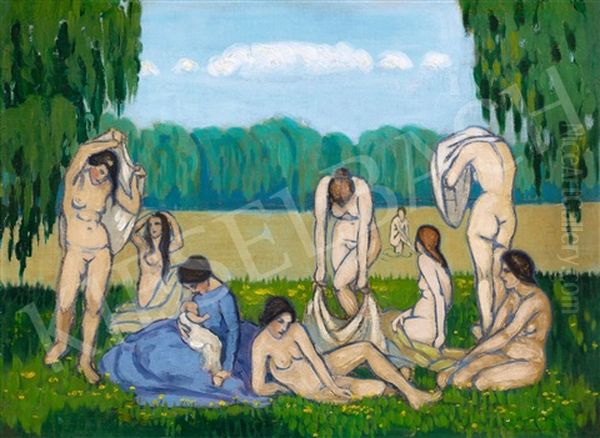

A recurring and central theme in Kernstok's oeuvre was the human figure. He was particularly drawn to depicting nudes, often in dynamic compositions such as riders or bathers. These figures were not merely academic studies but became vehicles for exploring concepts of natural harmony, primal energy, and the heroic potential of humanity. His figures are often monumental, imbued with a sense of strength and vitality, their forms simplified and stylized to emphasize their expressive power. The muscularity and dynamism of his figures, often set against simplified landscapes, convey a sense of timeless, almost mythical, power. This focus on the human form also connected with his broader philosophical concerns about individual transformation and the search for a new, harmonious relationship between humanity and nature. His later works would see a move towards even greater abstraction and a unique form of expressionism.

Representative Masterpiece: Horsemen at the Water's Edge

Among Kernstok's most celebrated works, Horsemen at the Water's Edge (Lovasok a vízparton), painted in 1910, stands as a quintessential example of his artistic vision and the ideals of "The Eight." Currently housed in the Hungarian National Gallery, this painting was a significant piece in the group's exhibitions. The work depicts nude male figures on horseback, their forms rendered with a powerful, almost sculptural solidity.

The composition is dynamic, with strong diagonal lines and a rhythmic interplay of forms. The colors are bold and expressive, yet controlled, contributing to the overall sense of monumental power. Kernstok simplifies the anatomy of both the men and the horses, reducing them to their essential masses and energetic contours. This simplification is not a lack of skill but a deliberate artistic choice, aiming to convey an archetypal vision of strength, freedom, and harmony with nature. The painting eschews anecdotal detail, focusing instead on the raw energy and structural coherence of the scene. It perfectly embodies Kernstok's synthesis of Cézanne's structural concerns with a more expressive, Fauvist-inspired vitality, and his philosophical interest in the heroic human form. Other artists like Franz Marc in Germany were contemporaneously exploring similar themes of animals and nature with expressive color, though Kernstok's approach retained a more classical, structural underpinning.

Social and Political Engagement

Kernstok was not an artist confined to his studio; he was actively engaged with the social and political currents of his time. He was a member of the Freemasons, a society that often attracted progressive intellectuals and artists. He played a role during the short-lived Hungarian Soviet Republic of 1919, reflecting his commitment to social change. However, this period was also fraught with complexities; an anecdote tells of his arrest due to a disagreement over literary principles with Béla Kun, a leader of the Republic, though he was subsequently released.

The collapse of the Hungarian Soviet Republic led to a period of political instability and repression, prompting Kernstok, like many other progressive artists and intellectuals, to emigrate. He spent time in Berlin, a vibrant center of avant-garde art in the 1920s, where he continued to develop his artistic practice. His engagement with social issues and his belief in art's role in societal transformation remained a consistent thread throughout his life, informing his artistic choices and his public activities.

The Berlin Years, Printmaking, and Later Interests

During his exile in Berlin in the 1920s, Kernstok's artistic interests expanded. He became increasingly involved in printmaking, particularly etching and copperplate engraving. His graphic works from this period are considered a significant part of his oeuvre, demonstrating his mastery of line and form in a different medium. These prints often continued his exploration of the human figure and dynamic compositions, translated into the starker, more linear language of print.

In his later years, Kernstok developed an interest in Italian Quattrocento art and a form of classical monumentalism. This shift might seem surprising given his avant-garde beginnings, but it can be seen as a search for enduring artistic values and a more universal formal language. This later classicism was not a regression but rather a reinterpretation of classical principles through a modern sensibility. Some art historians have noted parallels with the neoclassical phase of other major European artists of the period, such as Pablo Picasso, who also turned to classical sources for inspiration in the aftermath of World War I. Kernstok's engagement with monumental forms also found expression in designs for stained glass and mosaics, further broadening his artistic reach.

Collaborations and Wider Intellectual Circle

Károly Kernstok was deeply embedded in the rich cultural fabric of early 20th-century Hungary. His influence extended beyond "The Eight" and his direct artistic circle. He maintained close connections with leading figures in other artistic disciplines, reflecting the interdisciplinary nature of the avant-garde. He was associated with the radical poet Endre Ady, whose revolutionary verse resonated with the progressive spirit of artists like Kernstok.

He also had ties to the composer Béla Bartók, another towering figure of Hungarian modernism who, like Kernstok, sought to forge a new national cultural identity rooted in authentic traditions yet open to international innovation. These connections with writers and musicians underscore the holistic vision of cultural renewal shared by many Hungarian intellectuals of the era. Furthermore, Kernstok's engagement with philosophers like Lajos Fülep and György Lukács highlights the intellectual depth of his artistic project. He was not just a painter but a thinker, contributing to art theory through his writings and lectures, actively promoting the ideas of Cézanne and Matisse in Hungary. His circle also included artists like József Rippl-Rónai, an earlier pioneer of Hungarian Post-Impressionism, and younger contemporaries who were part of the broader modernist wave, such as Vilmos Perlrott-Csaba, who also absorbed Parisian influences.

Legacy and Historical Evaluation

Károly Kernstok's historical importance is multifaceted. He is unequivocally recognized as a pioneer of the Hungarian avant-garde, a catalyst who helped shift the course of Hungarian art towards modernism. As a founder and leading theorist of "The Eight," he played a crucial role in introducing and adapting the principles of international Post-Impressionism and Fauvism to a Hungarian context. His emphasis on "Explorative Art"—art that is intellectually driven, disciplined, and concerned with essential forms—provided a powerful counterpoint to purely imitative or overly sentimental approaches.

His artistic style, which evolved from a robust engagement with French modernism to a distinctive form of expressive monumentalism, left an indelible mark. Works like Horsemen at the Water's Edge remain iconic examples of Hungarian modernism. While some contemporary French critics may have questioned aspects of his historical painting, his overall contribution, particularly his synthesis of structural concerns with expressive power, is widely acknowledged. His lectures and writings further amplified his influence, educating a new generation of artists and shaping public understanding of modern art. Even artists who took different paths, such as the constructivist László Moholy-Nagy, emerged from the fertile ground of Hungarian avant-gardism that Kernstok helped cultivate.

Conclusion: An Enduring Influence

Károly Kernstok's life and work encapsulate the dynamism and intellectual fervor of early 20th-century European art. He was more than just a painter; he was an organizer, a theorist, and a cultural force who fundamentally reshaped the artistic landscape of Hungary. His commitment to an art that was both formally innovative and intellectually profound, his exploration of the human figure as a symbol of vitality and transformation, and his unwavering belief in art's social relevance continue to resonate. From the radical declarations of "The Eight" to the monumental classicism of his later years, Kernstok's journey reflects a relentless pursuit of artistic truth and a profound engagement with the defining questions of his era. His legacy endures in his powerful artworks and in his pivotal role as a bridge between Hungarian artistic traditions and the transformative currents of international modernism, securing his place as one of the most significant Hungarian artists of the modern age.