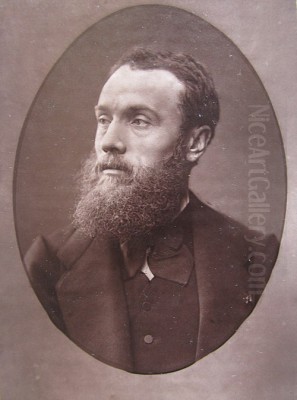

Jean-Paul Laurens (1838–1921) stands as one of the towering figures of late 19th-century French art, a painter and sculptor renowned as one of the last major exponents of the French Academic tradition, particularly in the genre of history painting. His career spanned a period of immense social and political upheaval in France, from the Second Empire through the entirety of the Third Republic, an era whose republican ideals he ardently championed through his powerful and often somber canvases. Laurens was not merely a painter of historical scenes; he was an interpreter of history, using his art to comment on power, religion, and the human condition, leaving behind a legacy of monumental works and a profound influence on a generation of artists.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Jean-Paul Laurens was born on March 28, 1838, in Fourquevaux, a small village in the Haute-Garonne department in southwestern France. His origins were humble, a background that perhaps instilled in him a certain resilience and a critical perspective on established hierarchies. His artistic talents emerged early, leading him to pursue formal training. In 1854, he enrolled at the École des Beaux-Arts in Toulouse, a significant regional art center. There, he studied under a painter named Jean-Baptiste Blaise Wimels, who likely provided him with his initial grounding in academic drawing and painting techniques.

The ambition of a young provincial artist in 19th-century France invariably led to Paris, the undisputed capital of the art world. Around 1860, Laurens secured the means, possibly through a municipal scholarship from Toulouse, to move to Paris and continue his studies at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts. This institution was the bastion of academic art, emphasizing rigorous training in drawing from the antique and the live model, perspective, anatomy, and the study of Old Masters.

In Paris, Laurens entered the ateliers of two prominent academic painters: Léon Cogniet and Alexandre Bida. Léon Cogniet (1794–1880) was a respected history painter, a winner of the Prix de Rome, and a member of the Académie des Beaux-Arts. He was known for works like Tintoretto Painting His Dead Daughter and for his portraits. Cogniet's studio would have reinforced the principles of grand historical composition and narrative clarity. Alexandre Bida (1813–1895), on the other hand, was particularly noted for his Orientalist scenes and biblical illustrations, characterized by their ethnographic detail and dramatic intensity. Bida's influence might be seen in Laurens's later attention to historical accuracy in costume and setting, as well as a certain dramatic flair.

This dual tutelage provided Laurens with a comprehensive academic education. He absorbed the emphasis on meticulous draughtsmanship, balanced composition, and the elevated subject matter—primarily historical, religious, or mythological—that defined the academic hierarchy of genres. His student years were marked by diligent study and the gradual development of his own artistic voice within the established conventions.

The Academic Path and Rise to Prominence

Laurens began to exhibit at the Paris Salon, the official annual or biennial art exhibition sponsored by the French government, which was the primary venue for artists to gain recognition and patronage. His Salon debut likely occurred in the early 1860s. Like many aspiring artists, he initially tackled subjects that were favored by the Salon juries, demonstrating his technical skill and his understanding of academic principles.

His breakthrough came with works that showcased his penchant for dramatic, often grim, historical episodes. He was particularly drawn to medieval and early modern history, often selecting moments of conflict, persecution, or tragic downfall. These themes resonated with the public's fascination with the past, but Laurens imbued them with a particular intensity and psychological depth.

In 1869, Laurens married Madeleine Willemsens, the daughter of his first teacher in Toulouse. This personal milestone coincided with his growing professional success. Throughout the 1870s and 1880s, he became one of the most acclaimed history painters in France. His works were frequently purchased by the state for national museums or commissioned for public buildings, a testament to his alignment with the cultural agenda of the Third Republic. He received numerous awards and honors, including election to the prestigious Académie des Beaux-Arts in 1891, succeeding Ernest Meissonier.

His success was built on a foundation of powerful, often large-scale canvases that were both meticulously researched and dramatically staged. He was a master of creating a sense of historical authenticity through careful attention to costume, architecture, and artifacts, yet he never allowed these details to overshadow the human drama at the core of his narratives. His figures were often depicted in moments of intense emotion or moral crisis, rendered with a sculptural solidity and a somber palette that enhanced the gravity of his themes.

Themes and Ideology: An Anti-Clerical Republican

Jean-Paul Laurens was a staunch republican and a fervent anti-clerical. These convictions profoundly shaped his choice of subject matter and the way he depicted historical events. In an era when the Third Republic was striving to consolidate its secular identity and distance itself from the monarchist and clerical influences of the past, Laurens's art often served as a powerful visual commentary on the dangers of religious fanaticism and autocratic rule.

He frequently chose subjects from medieval history, particularly episodes involving the abuse of power by the Church or by monarchs. His paintings often depicted scenes of excommunication, inquisitorial trials, or the suffering of those who defied religious or royal authority. These were not merely historical illustrations; they were allegories for contemporary concerns, reflecting the ongoing struggle between secular republicanism and the forces of reaction.

For example, his famous painting The Excommunication of Robert the Pious (1875, Musée d'Orsay, Paris) portrays the 10th-century French king and his queen, Bertha of Burgundy, recoiling in horror as papal legates pronounce their excommunication for an uncanonical marriage. The starkness of the scene, the despair of the royal couple, and the implacable authority of the Church create a powerful indictment of religious intolerance. Similarly, Pope Formosus and Stephen VI (also known as The Cadaver Synod, 1870, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nantes) depicts the macabre posthumous trial of Pope Formosus, whose corpse was exhumed, dressed in papal robes, and subjected to a mock trial by his successor. This gruesome scene highlights the corruption and brutality that could exist within the Church.

Other works, such as The Men of the Holy Office (or The Inquisition, 1889, Musée des Augustins, Toulouse), directly confronted the horrors of religious persecution. His depictions of Merovingian and Carolingian history also often focused on moments of cruelty and political intrigue, implicitly critiquing the violence inherent in monarchical systems. Through these historical narratives, Laurens articulated a vision of history as a struggle for freedom and reason against oppression and superstition, a vision that resonated deeply with the republican ethos of his time. He was, in many ways, the visual historian of the Third Republic's foundational myths and values.

Major Works and Artistic Style

Jean-Paul Laurens's artistic style was characterized by its academic rigor, dramatic intensity, and meticulous attention to historical detail. He was a superb draughtsman, and his compositions were carefully constructed to maximize narrative clarity and emotional impact. His figures, often rendered with a sculptural solidity, conveyed a sense of weight and presence.

His palette was typically somber, dominated by dark tones, browns, grays, and deep reds, which contributed to the gravity and often tragic mood of his scenes. However, he was also capable of using color for dramatic effect, highlighting key figures or moments with passages of brighter hue. His handling of light and shadow was masterful, often employing chiaroscuro to create a sense of depth and to focus the viewer's attention on the psychological core of the narrative.

Among his most significant works, several stand out:

The Excommunication of Robert the Pious (1875): As mentioned, this work is a prime example of his anti-clerical themes, showcasing his ability to convey intense emotion and the weight of historical events. The composition is stark, focusing on the despair of the royal couple.

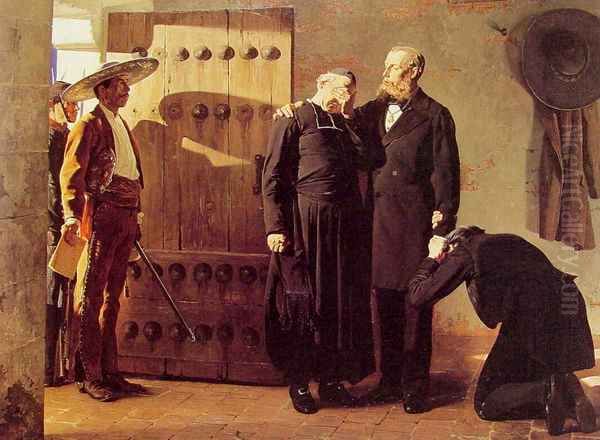

The Last Moments of Maximilian, Emperor of Mexico (1882, Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg): This painting depicts the Austrian Archduke Maximilian, installed as Emperor of Mexico by Napoleon III, facing his execution by firing squad. Laurens captures the dignity and pathos of the condemned emperor, creating a poignant commentary on the futility of imperial ambitions and the tragic consequences of political machinations. The work invites comparison with Édouard Manet's earlier series on the same subject, though Laurens's approach is more traditionally academic and overtly dramatic.

Pope Formosus and Stephen VI (The Cadaver Synod) (1870): A chilling depiction of a dark episode in papal history, this painting exemplifies Laurens's fascination with the macabre and his critique of ecclesiastical power. The ghoulish realism of the scene is unsettling and powerful.

The Men of the Holy Office (The Inquisition) (1889): This work portrays a group of inquisitors, their faces stern and implacable, embodying the cold, bureaucratic cruelty of religious persecution. The psychological intensity of the figures is a hallmark of Laurens's style.

The Death of Saint Genevieve (c. 1874–1880, Panthéon, Paris): Part of a larger decorative scheme, this work shows Laurens's ability to adapt his style to monumental public art while retaining his characteristic solemnity and historical focus.

Laurens's style, while firmly rooted in academic tradition, was not static. He was aware of contemporary artistic developments, though he remained largely aloof from the avant-garde movements like Impressionism, which he, like many academicians such as Jean-Léon Gérôme or William-Adolphe Bouguereau, likely viewed as a departure from the serious and elevated goals of art. His commitment was to history painting as a vehicle for moral and intellectual engagement, a genre he believed capable of conveying profound truths about the human experience. His approach can be compared to other great history painters of the 19th century, such as Paul Delaroche in an earlier generation, or contemporaries like Gérôme, though Laurens often brought a darker, more psychologically intense edge to his subjects.

Public Commissions and Monumental Art

The Third Republic, established in 1870, embarked on an ambitious program of public works and cultural patronage, seeking to create a visual identity for the new regime. Public buildings were adorned with paintings and sculptures that celebrated French history, republican values, and national heroes. Jean-Paul Laurens, with his established reputation and his alignment with republican ideals, was a natural choice for many of these prestigious commissions.

He created vast mural cycles for several important public buildings:

The Panthéon, Paris: Originally a church dedicated to Saint Genevieve, the patron saint of Paris, the Panthéon was secularized during the Revolution and transformed into a mausoleum for great French citizens. Under the Third Republic, it was re-decorated with murals depicting scenes from French history. Laurens was commissioned to paint scenes from the life of Saint Genevieve, including The Death of Saint Genevieve. These works, executed in a suitably grand and solemn style, contributed to the building's role as a national shrine.

The Hôtel de Ville (City Hall), Paris: After the original Hôtel de Ville was destroyed during the Paris Commune in 1871, it was rebuilt on an even grander scale. Laurens was commissioned to decorate several spaces, including the Salon Lobau, where he painted a series of murals depicting significant events in the history of Paris, such as Étienne Marcel leading the Parisian revolt in 1358. These works celebrated the city's long tradition of civic independence and resistance to tyranny. He also contributed to the decoration of the ceiling of the steel beams in one of the grand halls.

The Capitole, Toulouse: As a native of the region, Laurens was commissioned to decorate the Salle des Illustres (Hall of the Illustrious) in the Capitole, the city hall of Toulouse. His murals here depicted scenes from local history and celebrated regional figures, reinforcing a sense of local pride within the broader national narrative.

The Odéon Theatre, Paris: Laurens also contributed to the decoration of this historic Parisian theatre.

These monumental commissions allowed Laurens to work on a grand scale, creating immersive historical environments that engaged a wide public. His murals were not merely decorative; they were didactic, intended to educate citizens about their history and to instill republican virtues. In this, he was part of a broader movement of artists, including figures like Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, who sought to revive the tradition of monumental public art in France. However, Laurens's style remained distinct, characterized by its dramatic realism rather than Puvis's more allegorical and classicizing approach.

Laurens as an Educator

Beyond his prolific career as a painter, Jean-Paul Laurens was also a highly respected and influential teacher. He held professorships at two of the most important art institutions in Paris: the École des Beaux-Arts and the Académie Julian.

His appointment as a professor at the École des Beaux-Arts in 1891, the bastion of academic training, solidified his position within the artistic establishment. Here, he would have taught drawing, painting, and composition, passing on the principles of the academic tradition to a new generation of artists.

The Académie Julian, founded by Rodolphe Julian in 1868, played a crucial role in art education in Paris, particularly for students who could not, or chose not to, enter the official École des Beaux-Arts. It was known for its more liberal atmosphere and attracted a diverse international student body, including many women who were not yet admitted to the École. Laurens was one of its most prominent instructors. His atelier at the Académie Julian was highly sought after.

Among his many students were artists who went on to achieve significant recognition in various fields. These included:

His own sons, Paul-Albert Laurens (1870–1934) and Jean-Pierre Laurens (1875–1932), who both became painters.

George Barbier (1882–1932), who became a leading figure in Art Deco illustration and design.

André Gide (1869–1951), the future Nobel Prize-winning author, who briefly studied painting with Laurens before dedicating himself to literature.

René-Xavier Prinet (1861–1946), a French painter known for his intimate genre scenes and portraits.

Kahlil Gibran (1883–1931), the Lebanese-American writer, poet, and visual artist, studied with Laurens during his time in Paris.

American painter Cecilia Beaux (1855–1942) studied at the Académie Julian, benefiting from the instruction of masters like Laurens.

Canadian painter William Brymner (1855–1925) also studied under Laurens.

Japanese artists such as Nakamura Fusetsu (Fumio) and Kanokogi Takeshirō were among his pupils, indicating his international reach.

Laurens was known as a demanding but supportive teacher. He emphasized strong drawing skills and a thorough understanding of anatomy and composition, but he also encouraged his students to develop their own individual voices. His influence extended far beyond France, as many of his international students returned to their home countries, carrying with them the principles of his teaching. He was, in this sense, a key figure in the dissemination of French academic art practices at the turn of the century.

Contemporaries and Artistic Milieu

Jean-Paul Laurens operated within a vibrant and complex artistic milieu in late 19th-century Paris. He was a leading figure in the academic establishment, alongside other prominent history painters and Salon artists such as Jean-Léon Gérôme, William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Ernest Meissonier, and Luc-Olivier Merson. These artists shared a commitment to technical skill, narrative clarity, and elevated subject matter, though their individual styles and thematic preferences varied. Gérôme, for instance, was known for his highly polished historical and Orientalist scenes, while Bouguereau excelled in mythological and idyllic genre paintings. Meissonier was a master of small-scale, meticulously detailed military and historical subjects.

Laurens's particular brand of history painting, with its somber mood, psychological intensity, and anti-clerical undertones, carved out a distinct niche for him. While respected by his academic peers, he also maintained a certain independence.

The late 19th century was also the era of the avant-garde. Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Symbolism, and Fauvism successively challenged the dominance of academic art. Laurens, like most academicians, remained largely resistant to these new movements. He upheld the values of traditional craftsmanship and meaningful subject matter against what he likely perceived as the Impressionists' (like Claude Monet or Edgar Degas) fleeting concerns with light and sensation or the Post-Impressionists' (like Vincent van Gogh or Paul Gauguin) subjective distortions.

However, the art world was not entirely polarized. There were artists who bridged the gap between tradition and modernity, and Laurens, through his teaching at the Académie Julian, would have encountered students exploring a wide range of styles. While he himself did not embrace modernist aesthetics, his role as an educator placed him at a crossroads of artistic currents. The mention of a later artist like Georges Braque, a founder of Cubism, having studied with Léon Bonnat (a contemporary of Laurens and also an academic painter), illustrates the complex web of teacher-student relationships that connected different artistic generations. Laurens also had professional interactions with figures like the Symbolist-influenced painter Henri Martin, who also contributed to the Capitole de Toulouse decorations, suggesting a degree of collegiality across stylistic divides, particularly in the context of large public projects.

Personal Life and Anecdotes

While much of Jean-Paul Laurens's life was dedicated to his art and his teaching, some glimpses into his personal life exist. His marriage to Madeleine Willemsens in 1869 was a lasting one, and they had two sons, Paul-Albert and Jean-Pierre, who followed in his artistic footsteps. The family environment was likely one steeped in art and culture.

One rather unusual anecdote, mentioned in some biographical sources, concerns a difficult relationship between Laurens's wife and his mother-in-law, Collard Marguerite. According to this story, tensions ran so high that on one occasion, when Laurens attempted to join his wife in bed, his mother-in-law allegedly struck him with a stick. While such stories add a colorful, if somewhat peculiar, dimension to his biography, they are secondary to his artistic achievements. They do, however, hint at the personal dramas and complexities that can exist even in the lives of seemingly austere public figures.

Laurens was described by those who knew him as a man of strong convictions, serious and dedicated to his work. His anti-clericalism was not merely an artistic pose but a deeply held belief. He was a respected figure in the artistic and intellectual circles of Paris, a man whose work commanded attention and whose opinions carried weight.

Later Years, Death, and Legacy

Jean-Paul Laurens continued to paint and teach into the early 20th century, remaining a prominent figure even as the art world was increasingly dominated by modernist movements. He lived to witness the First World War, a cataclysm that profoundly reshaped European society and culture.

He died in Paris on March 23, 1921, at the age of 82. By the time of his death, academic history painting was largely considered an art form of the past. The avant-garde had triumphed, and the heroic, narrative, and moralizing ambitions of 19th-century history painting seemed out of step with the concerns of a new, disillusioned era. For a time, Laurens's reputation, like that of many academic artists, suffered a decline. His work was sometimes criticized as overly theatrical, didactic, or even, as some contemporary critiques noted, "ludicrous" in its dramatic intensity.

However, in more recent decades, there has been a significant re-evaluation of 19th-century academic art. Art historians have begun to look beyond the modernist narrative of inevitable progress and to appreciate academic artists like Laurens on their own terms. His technical mastery, his profound engagement with history, and his powerful visual storytelling are now recognized as significant achievements. His works are seen not merely as relics of a bygone era but as complex cultural documents that offer insights into the values, anxieties, and aspirations of late 19th-century France.

Laurens's legacy is multifaceted. He was one of the last great history painters in the grand academic tradition, a master of monumental public art, and an influential teacher who shaped a generation of artists. His paintings, with their dramatic intensity and their passionate defense of republican and anti-clerical ideals, remain powerful testaments to a pivotal era in French history. His works can be found in major museums in France and around the world, ensuring that his vision of history continues to engage and provoke viewers.

Conclusion: A Titan of a Bygone Era

Jean-Paul Laurens was more than just a skilled painter; he was a visual chronicler of his nation's past and a fervent advocate for its republican ideals. In an age of artistic revolution, he remained steadfastly committed to the traditions of history painting, believing in its power to educate, to inspire, and to convey profound moral truths. His canvases, often vast in scale and somber in tone, brought to life dramatic episodes from history, imbuing them with a psychological depth and an emotional intensity that captivated his contemporaries.

As a teacher, he transmitted the rigorous discipline of academic art to countless students, ensuring the continuation of a lineage of craftsmanship even as new artistic paradigms emerged. His monumental public commissions transformed civic spaces into arenas for historical reflection and republican pedagogy. While the artistic tastes of the 20th century initially led to a neglect of his work, Jean-Paul Laurens has rightfully been re-evaluated as a major figure in 19th-century European art, a "last grand master" whose powerful and often unsettling visions of the past continue to resonate with their dramatic force and intellectual depth.