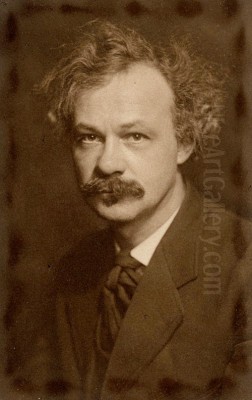

Jerome Myers (1867-1940) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in American art history. An artist and writer, he dedicated his career to capturing the vibrant, teeming life of New York City's immigrant neighborhoods, particularly the Lower East Side, with a distinctive blend of realism and heartfelt empathy. His work offers a unique window into the urban experience at the turn of the 20th century, focusing on the dignity, resilience, and quiet joys of its inhabitants. Unlike some of his contemporaries who emphasized the squalor of urban poverty, Myers sought out the human spirit and sense of community that flourished amidst challenging conditions.

Early Life and Formative Years

Born in Petersburg, Virginia, on March 20, 1867, Jerome Myers's early life was marked by instability and hardship. His father, Abram Myers, was often absent, leading the family—his mother, Julia, and four siblings—to move frequently. This peripatetic childhood, which included stays in Philadelphia and Baltimore, exposed young Jerome to various environments and likely fostered a keen observational sense. The family's financial struggles were significant, and by the age of eleven, Myers was already shouldering responsibilities, including caring for his ailing mother. These formative experiences undoubtedly cultivated a deep-seated empathy for the poor and marginalized, a theme that would become central to his artistic vision.

In 1886, at the age of nineteen, Myers moved to New York City, a decision that would profoundly shape his artistic trajectory. He initially found work as a scene painter and later as an illustrator for the New York Herald Tribune. Seeking formal artistic training, he enrolled at the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, a renowned institution offering free classes. He further honed his skills at the prestigious Art Students League, where he studied for eight years. Among his most influential instructors there was George de Forest Brush, an academic painter known for his idealized depictions of Native Americans and, later, Renaissance-inspired mother-and-child portraits.

Brush, like many academic artists of the time, advocated for traditional subjects and techniques. He reportedly discouraged Myers from pursuing urban life as a primary theme, viewing it as unsuitable for serious art. However, Myers felt an undeniable pull towards the bustling streets and diverse inhabitants of his adopted city. This burgeoning interest in the everyday life of New York's working class set him on a path distinct from the academic traditions espoused by teachers like Brush.

The Lure of the Lower East Side

A brief trip to Paris in 1896, while exposing him to European art, paradoxically solidified Myers's resolve to make New York City, and specifically its immigrant quarters, his lifelong subject. Upon his return, he immersed himself in the Lower East Side, a densely populated neighborhood teeming with newly arrived immigrants from Europe. He was captivated by the energy, the cultural diversity, and the daily dramas unfolding on its streets, in its markets, and within its tenements.

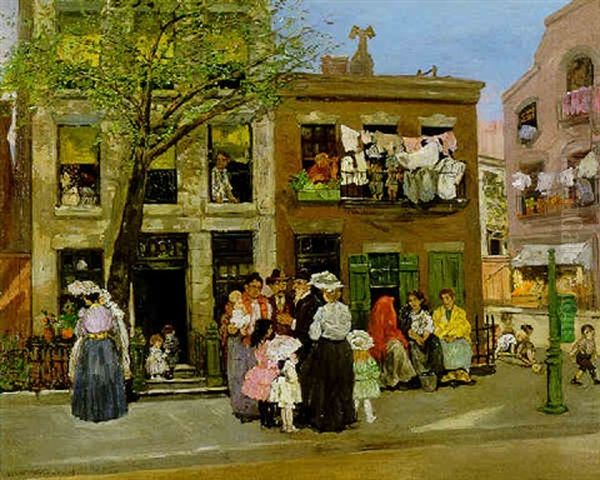

Myers chose to depict this world not with the stark, critical eye of a social reformer, but with the warm, sympathetic gaze of an intimate observer. He saw beauty and vitality where others might have seen only poverty and despair. His focus was on the human element: children playing in the streets, families gathering on stoops, vendors hawking their wares, and communities celebrating religious festivals. He was particularly drawn to the uninhibited joy and innocence of children, who feature prominently in many of his works. While some critics would later suggest his depictions occasionally veered into romanticization, Myers's intent was to highlight the resilience and enduring humanity of his subjects.

His commitment to these themes placed him in the vanguard of a new movement in American art that sought to engage directly with contemporary urban reality. This contrasted sharply with the prevailing tastes of the Gilded Age, which favored genteel portraits, idealized landscapes, and historical or mythological scenes, often championed by artists like John Singer Sargent or William Merritt Chase in their more society-oriented works.

Artistic Style and Techniques

Jerome Myers developed a distinctive artistic style characterized by soft, harmonious color palettes, a gentle rendering of form, and a focus on capturing atmosphere and mood. He worked proficiently across various media, including oil painting, watercolor, pastel, gouache, etching, and drawing. His early works often employed pen, crayon, and watercolor, but he increasingly turned to oils as his career progressed.

His compositions are typically filled with figures, yet they rarely feel chaotic. Instead, he masterfully arranged groups of people to convey a sense of community and shared experience. His use of light and shadow, often a subtle chiaroscuro, helped to model figures and create a sense of depth, lending a quiet drama to his everyday scenes. The colors are often muted but rich, contributing to the overall warmth and intimacy of his portrayals. He avoided the harsh outlines and bold, sometimes jarring, colors that characterized some modernist approaches emerging at the time.

Myers's technique was traditional in its foundations, emphasizing draftsmanship and careful composition. However, his application of these skills to contemporary urban subjects was innovative. He was less interested in photographic realism than in conveying the emotional essence of a scene. His figures, while clearly delineated, often possess a softness that enhances their sympathetic portrayal. This approach distinguished him from the more direct and sometimes gritty realism of photographers like Jacob Riis or Lewis Hine, who used their work as a tool for social reform, exposing the harsh conditions of slum life and child labor. Myers, while aware of these realities, chose to emphasize the positive aspects of community and human connection.

Key Works: Windows into a World

Several works stand out in Jerome Myers's oeuvre, each offering a poignant glimpse into the world he so lovingly depicted.

Sunday Morning (1907, oil on canvas, Delaware Art Museum) is one of Myers's most celebrated paintings. It portrays a bustling yet harmonious street scene in the Lower East Side. Figures are seen on fire escapes, children play, and adults converse, all under a soft, unifying light. The painting captures the leisurely pace of a Sunday, a day of rest and socializing for the working-class inhabitants. The colors are warm, and the overall atmosphere is one of communal well-being, despite the implied density of tenement living.

Children Playing (c. 1915, graphite on paper) exemplifies Myers's affinity for depicting the world of children. Whether in parks or on city streets, he captured their exuberance and imaginative play. This particular drawing, like many of his works focusing on children, highlights their ability to find joy and create their own worlds amidst the urban environment. It reflects his belief in the inherent vitality of youth, a recurring motif that brought a sense of optimism to his urban scenes.

They're in Church (1934, oil on canvas) showcases another important facet of immigrant life: religious observance and community gathering. Myers often depicted scenes related to religious festivals and gatherings, recognizing their importance in maintaining cultural identity and providing communal support. This work likely portrays a quiet moment of shared faith, rendered with his characteristic sensitivity.

Artist in Manhattan (1940) is not only the title of a painting but also of his autobiography, published posthumously in the year of his death. The book provides invaluable insights into his life, his artistic philosophy, and his experiences in the New York art world. The painting itself likely reflects his deep connection to the city as both his home and his primary source of inspiration, perhaps showing an artist (possibly himself) observing or sketching the urban scene.

Other notable works include The Tambourine (1905), Evening, Myers's Studio (c. 1910-1912), The End of the Street (1907), and numerous etchings and drawings that capture fleeting moments of street life with remarkable tenderness. His etchings, in particular, allowed him to explore tonal variations and capture the atmospheric qualities of the city with a different kind of intimacy.

The Ashcan School and Urban Realism

Jerome Myers is most closely associated with the Ashcan School, a group of artists who sought to portray contemporary American city life with unvarnished realism. While not one of "The Eight" who famously exhibited at the Macbeth Galleries in 1908 (Robert Henri, John Sloan, William Glackens, George Luks, Everett Shinn, Arthur B. Davies, Ernest Lawson, and Maurice Prendergast), Myers shared their commitment to depicting the urban environment and its diverse inhabitants. He was a kindred spirit, and his studio was near those of many Ashcan artists.

The spiritual leader of the Ashcan School, Robert Henri, urged artists to paint "life" and to find beauty in the everyday, even in the seemingly coarse or mundane aspects of the city. Artists like John Sloan captured the vitality of city life in works like McSorley's Bar, while George Luks depicted the boisterous energy of the streets in paintings such as Hester Street. Everett Shinn focused on the theater and the more dramatic aspects of urban entertainment.

Myers's approach, however, was often gentler and more lyrical than that of some of his Ashcan colleagues. While Henri and Sloan might emphasize the grit and raw energy of the city, Myers often imbued his scenes with a poetic quality. He was sometimes referred to as the "gentle poet of the slums," a testament to his sympathetic and often romanticized view of his subjects. This distinguished his work from the more overtly critical or satirical edge found in some Ashcan art. Despite these nuances, his dedication to urban themes firmly places him within the broader currents of American realism that the Ashcan School championed. His focus on immigrant communities also provided a specific lens that complemented the wider urban narratives of his peers.

The Armory Show and the AAPS

Beyond his individual artistic practice, Jerome Myers played a crucial role in organizing one of the most transformative art exhibitions in American history: the International Exhibition of Modern Art, better known as the Armory Show of 1913. Myers was a founding member of the Association of American Painters and Sculptors (AAPS), the group responsible for organizing this landmark event. He served on various committees, including the domestic exhibition committee.

The AAPS was formed in 1911 by Myers, Walt Kuhn, Elmer MacRae, and others, with Arthur B. Davies later becoming its president. Their goal was to create opportunities for progressive American artists to exhibit their work outside the conservative confines of institutions like the National Academy of Design, which tended to favor academic art. The Armory Show was their most ambitious undertaking.

Held at the 69th Regiment Armory in New York City, the exhibition introduced the American public and artists to European avant-garde movements on an unprecedented scale. Works by artists such as Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Marcel Duchamp (whose Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 caused a particular sensation), Constantin Brancusi, Wassily Kandinsky, and Georges Braque were displayed alongside works by contemporary American artists, including Myers himself.

The Armory Show was a watershed moment. It shocked and scandalized many conservative critics and viewers but also galvanized American artists, exposing them to new modes of expression like Cubism, Fauvism, and Futurism. For Myers, while his own style remained rooted in a more traditional realism, his involvement in organizing the show demonstrated his commitment to artistic freedom and the promotion of new art. He believed in the importance of artists controlling their own exhibition opportunities and fostering a more inclusive art world.

A Unique Vision: Myers in Context

Jerome Myers carved out a unique niche within the landscape of early 20th-century American art. His sympathetic portrayal of immigrant life in New York City offered a counter-narrative to the more sensationalized or purely sociological depictions of the urban poor. While photographers like Jacob Riis, in his groundbreaking work How the Other Half Lives, exposed the dire conditions of tenement life to spur social reform, Myers sought to reveal the humanity and community that persisted within those same environments. Similarly, Lewis Hine's photographs documented child labor and the experiences of immigrants at Ellis Island with a powerful, reformist agenda.

Myers's art, by contrast, was less about exposé and more about celebration – a quiet celebration of everyday existence, of cultural traditions maintained in a new land, and of the universal experiences of childhood, family, and community. His work resonates with a sense of optimism, even when depicting scenes of poverty. This optimistic and often idealized lens led some contemporary and later critics to view his work as overly sentimental or romanticized, particularly when compared to the grittier realism of some Ashcan artists or the stark documentation of social photographers.

However, this very quality is also a source of his work's enduring appeal. Myers offered a vision of the city that acknowledged hardship but emphasized resilience, dignity, and the vibrant tapestry of human life. His focus on the Lower East Side provided a specific cultural context, capturing the experiences of Jewish, Italian, Irish, and other immigrant groups as they navigated life in America. In this, his work can be seen as an early form of multicultural representation in American art.

His contemporaries included a wide range of artists. Beyond the Ashcan circle, figures like Childe Hassam were creating Impressionist views of a more genteel New York, while Alfred Stieglitz and the Photo-Secessionists were championing photography as a fine art, often with urban themes. Later, artists like Edward Hopper would explore urban alienation with a starker, more modernist sensibility, and Reginald Marsh would depict the teeming crowds and burlesque houses of New York with a raw energy. Myers's contribution lies in his consistent, compassionate focus on the communal life of immigrant neighborhoods.

Later Career, Recognition, and Awards

Throughout his career, Jerome Myers received growing recognition for his unique contribution to American art. He exhibited regularly and his work began to enter important public and private collections. His participation in the Armory Show, despite the stylistic differences between his work and the European avant-garde, raised his profile.

He was honored with several prestigious awards, reflecting the art world's increasing appreciation for his work. These included the National Academy of Design's Isidor Gold Medal (1918 and 1937), the Clarke Prize (1919), the Second Altman Prize (1931 and 1937), and the Carnegie Prize from the National Academy of Design (1936). He also received a bronze medal at the St. Louis Exposition in 1904.

His works were acquired by major institutions, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Phillips Collection in Washington D.C., the Brooklyn Museum, the Delaware Art Museum, and the Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester, among others. This institutional recognition solidified his place in the canon of American art.

Despite failing health in his later years, Myers continued to paint and draw. He also dedicated time to writing his autobiography, Artist in Manhattan, which was published in 1940, the year of his death. The book offers a rich, personal account of his artistic journey and his observations of the New York art scene over several decades.

Personal Life and Anecdotes

Jerome Myers's personal life was intertwined with his artistic pursuits. His early experiences of poverty and family responsibility deeply shaped his worldview and artistic focus. The story of him caring for his mother and siblings from the age of eleven underscores his resilience and empathy.

His brief sojourn in Paris was pivotal. Though he only stayed a few months, the experience of being abroad seemed to clarify his artistic mission: to return to New York and dedicate himself to chronicling its life. This decision speaks to his profound connection to the city.

Myers was not just a painter; he was also a writer. His 1923 magazine article detailing life in the Lower East Side demonstrates his keen observational skills and his ability to articulate his insights in prose as well as paint. This literary inclination culminated in his autobiography.

He married fellow artist Ethel Myers (née Klinck), a talented sculptor and painter in her own right. Ethel was a strong supporter of Jerome's work and, after his death, became a dedicated custodian of his legacy.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Jerome Myers passed away in New York City on June 19, 1940, at the age of 73, in his studio at the National Arts Club. He left behind a significant body of work that continues to resonate for its warmth, humanity, and historical value.

His wife, Ethel Myers, played a crucial role in preserving and promoting his artistic achievements after his death. She organized exhibitions of his work and, notably, established the Jerome Myers Memorial Gallery in New York City to ensure his art remained accessible to the public.

Today, Jerome Myers is recognized as an important chronicler of early 20th-century New York City, particularly its immigrant communities. His paintings, drawings, and prints offer invaluable visual records of a bygone era, capturing the sights, sounds, and spirit of places like the Lower East Side. While the Ashcan School often receives more attention for its broader impact on American realism, Myers's specific focus and sympathetic approach provide a unique and complementary perspective.

His work continues to be studied and appreciated for its artistic merit, its historical significance, and its compassionate portrayal of urban life. He reminds us that even in the most challenging circumstances, human dignity, community, and joy can flourish. His art stands as a testament to the vibrant cultural tapestry of immigrant America and the enduring power of empathy in artistic expression. Artists like Raphael Soyer and Isaac Soyer, who also depicted urban life and working-class people in later decades, can be seen as inheritors of a tradition to which Myers contributed significantly.

Conclusion

Jerome Myers was more than just a painter of city scenes; he was a visual poet of the urban experience. His deep empathy, cultivated through a challenging early life, allowed him to connect profoundly with the immigrant communities of New York's Lower East Side. He chose not to dwell on the squalor or despair, but to seek out and celebrate the resilience, vitality, and communal spirit of its inhabitants. As a key figure associated with the Ashcan School and an instrumental organizer of the groundbreaking Armory Show, Myers played a significant role in the development of American modernism, even as his own style retained a gentle, humanistic realism. His legacy endures in his evocative portrayals of a city in transition and in his unwavering belief in the inherent dignity of all people.