John Sloan stands as a pivotal figure in the landscape of early 20th-century American art. An influential painter and etcher, he was a leading force within the Ashcan School and a core member of The Eight, movements that sought to capture the unvarnished reality of modern American life, particularly in the burgeoning metropolis of New York City. His work provides an invaluable visual record of an era, marked by its empathy, keen observation, and rejection of academic gentility in favor of the vibrant, often gritty, pulse of the everyday.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings in Philadelphia

John Sloan was born on August 2, 1871, in Lock Haven, Pennsylvania. His family relocated to Philadelphia during his childhood, a city that would prove formative for his artistic development. Financial difficulties prevented Sloan from pursuing higher education in a conventional sense after high school. Instead, he took jobs, including one at a bookstore, Porter & Coates, which inadvertently fostered his artistic inclinations by exposing him to prints and illustrations. He began teaching himself to draw and etch, demonstrating an early aptitude and independent spirit.

His professional career began not in fine art, but in commercial illustration. He worked for The Philadelphia Inquirer starting in 1892, joining its art department. This period was crucial not only for honing his drafting skills under the pressure of deadlines but also for the connections he made. It was here he befriended Robert Henri, William Glackens, George Luks, and Everett Shinn – artists who would later form the nucleus of the Ashcan School. Henri, recently returned from studying in Europe and brimming with ideas about modern art, became a significant mentor and lifelong friend, encouraging Sloan and the others to move beyond illustration towards painting.

While working as an illustrator, Sloan also sought formal training, taking evening classes at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) under Thomas Anshutz, himself a student of the great realist Thomas Eakins. This connection placed Sloan within a lineage of American realism, though his path would diverge significantly from academic traditions. By 1895, Sloan moved to the Philadelphia Press, where he produced intricate, full-color illustrations and decorative puzzles, often employing an Art Nouveau-influenced "poster style" that drew inspiration from European artists and Japanese prints. Despite his success in this field, the desire to pursue painting as a primary form of expression grew, fueled by Henri's encouragement.

The Move to New York and the Ashcan School

Following the lead of Henri and others from their Philadelphia circle, Sloan moved to New York City in 1904. This relocation marked a turning point in his career and life. New York, with its teeming streets, diverse population, and stark social contrasts, provided Sloan with an inexhaustible source of subject matter. He immersed himself in the city's energy, finding inspiration in the everyday lives of ordinary New Yorkers, particularly the working class and immigrants inhabiting neighborhoods like Greenwich Village, where he eventually settled.

Sloan became a central figure in what would later be dubbed the Ashcan School. This was not a formal organization but rather a group of artists united by a shared philosophy, largely championed by Robert Henri, emphasizing the depiction of contemporary urban reality. They rejected the idealized subjects and polished techniques favored by the National Academy of Design, turning instead to the raw, unglamorous aspects of city life: crowded tenements, bustling markets, smoky bars, laundry-strewn rooftops, and moments of leisure snatched by working people.

Sloan's approach was characterized by a deep sense of empathy and observation. He often depicted scenes viewed from his apartment window or sketched during long walks through the city. His paintings from this period, typically rendered in a darker palette influenced by seventeenth-century Dutch and Spanish masters like Frans Hals and Diego Velázquez, as well as contemporaries like Édouard Manet, capture the fleeting moments and textures of urban existence. He focused on human interaction and the environment that shaped it, presenting his subjects without overt sentimentality or moral judgment.

The Eight and the Challenge to the Establishment

The prevailing art institution of the time, the National Academy of Design, adhered to conservative tastes, often favoring European-influenced academic styles and genteel subjects. Robert Henri and his circle found their more realistic, gritty depictions of American life frequently rejected from the Academy's juried exhibitions. In response to this perceived exclusivity and resistance to newer forms of expression, Henri decided to organize an independent exhibition.

This led to the formation of "The Eight," a group comprising Henri, Sloan, Glackens, Luks, Shinn, Arthur B. Davies, Ernest Lawson, and Maurice Prendergast. While the first five shared the urban realist focus associated with the Ashcan School, Davies, Lawson, and Prendergast worked in distinctly different, more modernist or impressionistic styles. What united them was their opposition to the Academy's stranglehold and their desire for artistic independence.

Their landmark exhibition was held at the Macbeth Galleries in New York City in February 1908. It was a succès de scandale, attracting significant public attention and critical debate. While some critics were dismissive, others recognized the vitality and Americanness of the work. The exhibition was seen as a direct challenge to the established art world and is considered a crucial event in the history of American modernism, paving the way for greater acceptance of diverse artistic styles and subject matter. Sloan was a key participant, exhibiting works that exemplified the Ashcan focus on urban reality.

Sloan's Artistic Style: Realism, Observation, and Influence

John Sloan's style evolved throughout his long career, but its foundation remained rooted in realism and direct observation. In his early New York paintings, he employed a relatively dark palette, using vigorous brushwork to capture the energy and atmosphere of the city. He was a master of depicting artificial light – the glow from shop windows, the glare of streetlights, the intimate illumination within tenement rooms – and its effect on urban spaces and figures.

A significant influence on Sloan's compositional approach was Japanese ukiyo-e prints, which he collected. The unconventional cropping, flattened perspectives, and focus on everyday life found in works by artists like Hokusai and Hiroshige resonated with Sloan's own interest in capturing candid moments. This influence is visible in the dynamic arrangements and sometimes voyeuristic viewpoints of his city scenes.

While primarily known for his urban subjects, Sloan did not limit himself entirely. Encouraged by Henri, he took up landscape painting, particularly during summers spent in Gloucester, Massachusetts, and later, Santa Fe, New Mexico. These works often feature a brighter palette and explore different atmospheric effects, though they retain his characteristic robust handling of paint.

In his later career, particularly from the late 1920s onwards, Sloan experimented with technique. He developed a complex system involving tempera underpainting and oil glazes, building up layers to achieve luminosity and depth. He also focused increasingly on the female nude, applying a distinctive cross-hatching modeling technique with fine brushes to define form, a method that set these works apart stylistically from his earlier, more broadly painted canvases.

Masterpieces of Urban Life: Key Works

Sloan's body of work is rich with iconic depictions of New York City. Among his most celebrated paintings are:

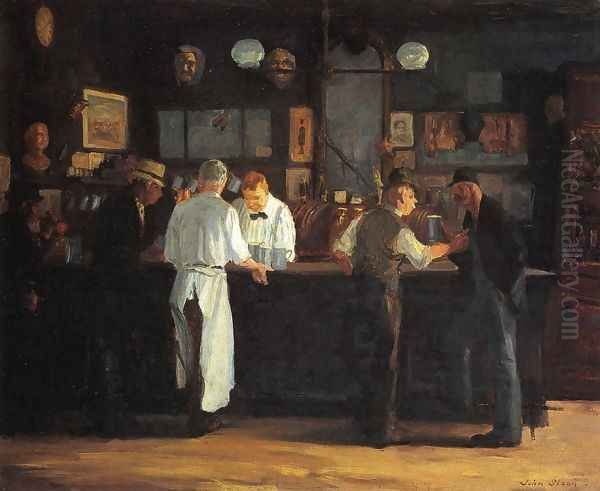

_McSorley's Bar_ (1912): Perhaps his most famous painting, it captures the exclusively male atmosphere of the historic New York saloon. The warm, dim lighting, the clutter of memorabilia, and the unposed attitudes of the patrons create a powerful sense of place and time. It exemplifies the Ashcan School's focus on working-class leisure.

_Sixth Avenue Elevated at Third Street_ (1928): This later work showcases Sloan's enduring fascination with the city's infrastructure and energy. The elevated train structure dominates the composition, casting dramatic shadows, while life unfolds on the street below. It reflects his continued engagement with the urban landscape, albeit with a potentially more structured approach than his earliest works.

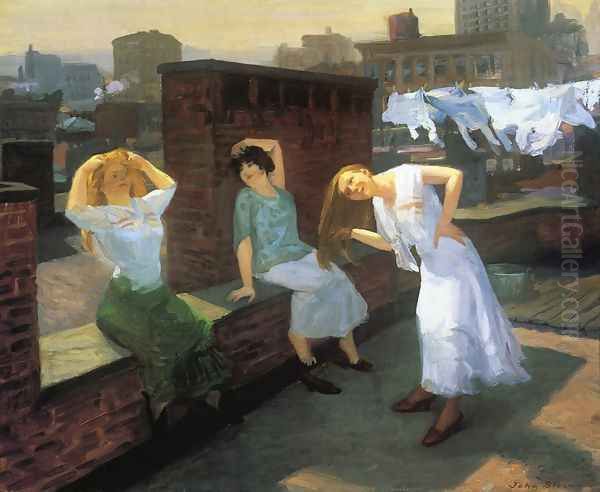

_Sunday, Women Drying Their Hair_ (1912): Depicting women on a tenement rooftop engaged in a simple, communal activity, this painting offers an intimate glimpse into the private lives of city dwellers. The viewpoint, seemingly from an adjacent window, adds a layer of voyeurism typical of Sloan's work, yet the treatment is empathetic rather than exploitative.

_The Wake of the Ferry II_ (1907): A moody, atmospheric piece showing passengers on a ferry receding from the viewer into the mist. It contrasts with the brighter palettes of American Impressionists like Childe Hassam, showcasing Sloan's preference for a more somber, evocative realism.

_Yeats at Petitpas'_ (1910): This group portrait depicts the Irish poet W.B. Yeats holding court at a boarding house restaurant frequented by artists and writers, including Sloan himself (seen with his back to the viewer). It captures the intellectual and bohemian milieu of Greenwich Village.

These paintings, along with others like Dust Storm, Fifth Avenue (1906), Chinese Restaurant (1909), and The City from Greenwich Village (1922), solidify Sloan's reputation as a preeminent visual poet of early 20th-century New York.

Etching and Illustration: A Parallel Practice

Alongside his painting, John Sloan was a prolific and highly accomplished etcher. He considered etching not merely a secondary activity but an essential part of his artistic output, allowing for different expressive possibilities and wider dissemination of his images. He produced around 300 etchings throughout his career.

His most famous series of etchings is New York City Life (1905-1906), a portfolio that encapsulates his observations of the city's inhabitants. Plates like Turning Out the Light, Man, Wife and Child, and Roofs, Summer Night offer candid, sometimes humorous, sometimes poignant vignettes of tenement life. These etchings share the thematic concerns of his paintings but often possess a linear energy and narrative clarity unique to the medium.

Sloan's background in illustration remained relevant. Even after focusing on painting, he continued to create illustrations, notably for socialist publications like The Masses. His skill as a draftsman, honed during his newspaper years, underpinned all his work. He valued the democratic potential of printmaking, seeing it as a way to make art accessible beyond the confines of galleries and museums. His early "poster style" illustrations for the Philadelphia Press are also recognized for their graphic inventiveness.

A Dedicated Educator: The Art Students League

From 1916 until 1938 (with some interruptions), John Sloan was a highly respected and influential teacher at the Art Students League of New York. He succeeded his mentor, Robert Henri, and carried forward a similar philosophy of encouraging individuality and finding inspiration in life. His students included notable artists who would make their own marks on American art, such as Reginald Marsh, known for his bustling scenes of New York, Alexander Calder, the inventor of the mobile, and Barnett Newman, a key figure in Abstract Expressionism.

Sloan was known for his engaging, often witty, teaching style. He emphasized the importance of drawing and understanding form but urged students to develop their own vision rather than merely imitating his style. He famously encouraged them to find joy in the process of creation, advising them not to rely solely on art for their livelihood if it compromised their artistic integrity. His teachings, compiled and published posthumously by Helen Farr Sloan as Gist of Art, continue to offer insights into his artistic philosophy. Other prominent artists associated with the League during this era, though not necessarily direct students of Sloan, included Stuart Davis and Yasuo Kuniyoshi.

Social Conscience and Political Engagement

John Sloan possessed a strong social conscience, deeply sympathetic to the working class and critical of social inequality. This perspective informed his choice of subject matter, lending an inherent social commentary to his depictions of urban life, even when not overtly political. His empathy for the struggles and small pleasures of ordinary people is palpable in his work.

His political convictions led him to join the Socialist Party of America in 1910. He became actively involved, serving as the acting art editor (and later contributing editor) for the radical monthly magazine The Masses from 1912 to 1916. He contributed numerous drawings and cartoons, often satirical, critiquing capitalism, war, and social injustice. He worked alongside other politically engaged artists like Art Young, Boardman Robinson, and Stuart Davis at the magazine. However, Sloan eventually resigned from The Masses due to editorial disputes regarding the relationship between text and images, believing captions should not dictate the interpretation of artwork. Despite this break, his commitment to social justice remained a consistent thread in his life and art.

Later Years: Santa Fe and Evolving Visions

Beginning in 1919, Sloan and his first wife, Dolly, began spending summers in Santa Fe, New Mexico. After Dolly's death in 1943, he married Helen Farr, a former student who became a devoted champion of his work and legacy. The Southwestern landscape and its distinct cultures offered Sloan new artistic stimuli. He became fascinated by the desert light, the dramatic geography, and the ceremonies of the Pueblo people.

His Santa Fe works represent a significant shift in subject matter and, to some extent, style. Paintings like Travelling Carnival, Santa Fe (1924) show his continued interest in everyday life, but his landscapes and depictions of Native American dances introduced brighter colors and more rhythmic compositions. He became an advocate for Native American artists and played a role in the Society of Independent Artists' decision to exhibit their work without a jury.

During this later period, Sloan also dedicated considerable energy to studio work, focusing on the female nude and refining his complex glazing and cross-hatching techniques. While these later figure paintings were stylistically different from his Ashcan work and sometimes less critically acclaimed during his lifetime, they represent an important phase of his continuous artistic exploration. He continued to paint and etch with vigor into his old age.

Legacy and Historical Evaluation

John Sloan died on September 7, 1951, in Hanover, New Hampshire, while visiting his wife's family. He left behind a rich and varied body of work that secured his place as one of the most important American artists of the first half of the 20th century. His historical significance rests on several key contributions:

Pioneering American Realism: As a leader of the Ashcan School and The Eight, Sloan was instrumental in shifting the focus of American art towards contemporary, native subject matter, challenging the dominance of European academicism and genteel Impressionism.

Chronicler of Urban Transformation: His paintings and etchings provide an unparalleled visual record of New York City during a period of rapid growth and social change, capturing its energy, diversity, and contradictions with honesty and empathy.

Master Printmaker: Sloan elevated the status of etching in America, demonstrating its potential for powerful artistic expression and social observation. His New York City Life series remains a landmark in American printmaking.

Influential Teacher: Through his long tenure at the Art Students League, he shaped a generation of American artists, instilling values of independent vision and connection to lived experience. His influence can be seen in the work of Social Realists and other artists who depicted American life, such as Reginald Marsh and Isabel Bishop.

Advocate for Artistic Freedom: His involvement with The Eight and the Society of Independent Artists (which he helped found and served as president) demonstrated a lifelong commitment to challenging institutional conservatism and promoting opportunities for artists outside the academic mainstream, anticipating movements like the Armory Show of 1913 (in which he also participated).

While initially met with resistance from conservative critics, Sloan's work gained widespread recognition over time. Today, he is celebrated for his technical skill, his humanistic vision, and his crucial role in defining a distinctly American modern art. His legacy is carefully preserved, notably at the Delaware Art Museum, which holds a major collection of his works and archival materials, largely thanks to the efforts of his widow, Helen Farr Sloan. He remains a vital figure, studied not only for his artistic achievements but also for his insights into the American experience at the dawn of the modern era, standing alongside figures like George Bellows and Edward Hopper as defining interpreters of American realism.