John Linnell stands as a significant, albeit sometimes complex, figure in the rich tapestry of 19th-century British art. Born in London on June 16, 1792, and living a long and productive life until January 20, 1882, Linnell excelled as a painter of both portraits and landscapes, and also possessed considerable skill as an engraver and miniaturist. He navigated the dynamic art world of his time, forging crucial relationships, developing a distinct naturalistic style, and achieving considerable commercial success, even while maintaining a somewhat contentious relationship with the art establishment, particularly the Royal Academy. His legacy is intertwined with that of the visionary poet and artist William Blake, whom he supported, and with the development of a particular strain of intense, detailed landscape painting that captured the English countryside with unique fervour.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

John Linnell's entry into the world of art seemed almost predestined. Born in Bloomsbury, London, his father, James Linnell, was a carver, gilder, and picture dealer. Recognizing his son's burgeoning talent at a young age, James employed young John in the business, initially having him copy the works of popular artists like the rustic scene painter George Morland. These copies were then sold, providing an early, practical immersion in the art market. This early exposure, however, was more than just commercial; it honed his observational skills and draughtsmanship.

His formal training began under the guidance of the esteemed watercolourist John Varley, a pivotal figure in the development of British landscape painting. Varley's studio was a hub of artistic activity, and Linnell benefited immensely from his instruction and the company of other aspiring artists. Varley encouraged direct observation of nature, a principle that would become central to Linnell's own artistic philosophy. During this period, he also formed lasting friendships, including one with William Henry Hunt, another prominent watercolourist known for his detailed still lifes and rustic figures.

In 1805, at the young age of thirteen, Linnell was admitted to the prestigious Royal Academy Schools. Here, he studied under notable figures and alongside talented contemporaries, including William Mulready. The president of the Royal Academy at the time was the influential American-born painter Benjamin West. Linnell quickly distinguished himself, winning medals for drawing and modelling. He first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1807, marking the public start of a long and prolific exhibiting career.

Forging a Path: Portraiture and Naturalism

Initially, Linnell relied heavily on portraiture to establish his career and secure an income. He demonstrated a keen ability to capture likenesses, working in oils and also producing miniatures, a highly sought-after format at the time. His sitters included prominent figures, intellectuals, and fellow artists. Notable examples include his sensitive portrait of his teacher John Varley and likenesses of figures such as the political economist Thomas Malthus. A portrait like Miss Jane Puxley showcases his skill in rendering character and detail within the conventions of the genre.

However, Linnell's true passion lay in landscape painting. Influenced by his training with Varley, the works of 17th-century Dutch masters, and an innate inclination towards detailed observation, he began to explore the English countryside. Around 1811, he embarked on sketching tours, sometimes accompanied by fellow artist Cornelius Varley (John Varley's brother), focusing on capturing the effects of light and atmosphere directly from nature. This period marked his commitment to a form of naturalism that sought fidelity to the specific details of a scene.

An early, striking example of this approach is Kensington Gravel Pits (1811-12). This painting, depicting labourers excavating gravel on the outskirts of London, was notable for its unidealized subject matter and its meticulous attention to geological detail and the textures of the earth. While admired by some for its truthfulness, its departure from picturesque conventions also drew criticism, highlighting Linnell's willingness to challenge prevailing tastes in pursuit of observed reality. This dedication to empirical study would remain a hallmark of his landscape work.

The Encounter with William Blake

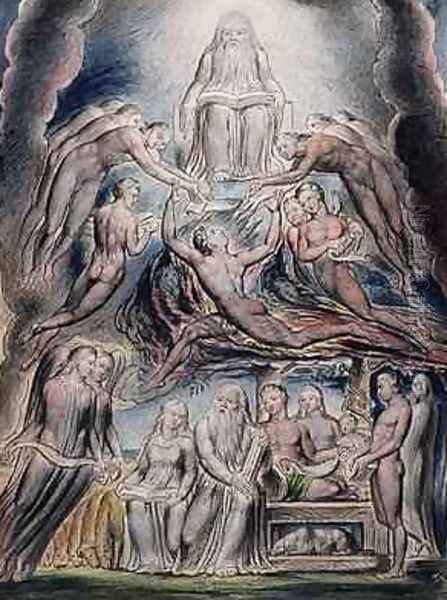

One of the most significant relationships in John Linnell's life, and one crucial to art history, was his friendship with William Blake. Introduced around 1818, possibly through George Cumberland or John Varley, Linnell quickly became one of Blake's most important patrons and staunchest supporters during the poet-artist's later years, when recognition and financial stability were scarce. Linnell possessed a practical acumen that complemented Blake's visionary intensity.

Recognizing Blake's genius, Linnell commissioned two of his most celebrated series: the twenty-two engravings for the Book of Job and the watercolour illustrations, later engraved, for Dante's Divine Comedy. The Job engravings, in particular, are considered a pinnacle of Blake's artistic achievement, and Linnell's role in facilitating their creation was indispensable. He not only provided the commission but also managed aspects of the engraving process and distribution.

Their relationship extended beyond patronage; it involved intellectual exchange and mutual respect, despite their differing temperaments and religious outlooks (Linnell was a devout Baptist, Blake a unique mystic). Linnell admired Blake's spiritual depth, while Blake benefited from Linnell's grounded support. Linnell also played a crucial role in introducing Blake to a younger generation of artists who were deeply inspired by his visionary work.

Linnell and 'The Ancients'

Through his connection with Blake, Linnell became associated with a group of young artists who gathered around the elder visionary in his final years. This group, who informally called themselves 'The Ancients', included figures like Samuel Palmer, George Richmond, and Edward Calvert. They were drawn to Blake's rejection of materialism and his embrace of spiritual and imaginative art, looking back to earlier forms of art for inspiration, hence their name.

Linnell acted as a mentor figure and a bridge between Blake and these younger artists. He introduced Samuel Palmer to Blake in 1824, an encounter that profoundly impacted Palmer's artistic development. The Ancients revered Blake and were inspired by his intense, spiritual interpretations of the world. While Linnell shared their admiration for Blake and a deep love for the English landscape, his own artistic approach remained more grounded in naturalistic observation compared to the often mystical and stylized work of Palmer and others in the Shoreham period.

The connection became familial when Linnell's eldest daughter, Hannah, married Samuel Palmer in 1837. Although Linnell's relationship with Palmer would later become strained, his initial support and connection to this circle were vital in fostering a unique strand of British Romantic art centered around Shoreham, Kent, where Palmer produced some of his most iconic, visionary landscapes. Other artists associated with or influenced by this circle included Francis Oliver Finch.

Master of the English Landscape

While portraiture continued to provide income, Linnell's reputation grew primarily through his landscape painting from the 1820s onwards. He developed a distinctive style characterized by meticulous detail, dramatic effects of light and weather, and often imbued with a sense of divine presence in nature. His favoured subjects were the rolling hills, woods, and agricultural scenes of the English home counties, particularly Surrey and Kent.

Works like Windsor Forest demonstrate his ability to handle complex compositions and render the textures of foliage and bark with precision. He was particularly adept at capturing the changing moods of the sky, from the tranquil glow of sunset in paintings like The Harvest Moon to the dramatic intensity of approaching storms, as seen in works simply titled Storm. These paintings often went beyond mere topography, suggesting deeper symbolic or religious meanings.

Linnell frequently depicted scenes of rural labour, such as harvesting and woodcutting. Paintings like Reapers, Noonday Rest show agricultural workers integrated into the landscape, reflecting both an observation of contemporary rural life and perhaps an underlying commentary on man's relationship with nature and toil. His landscapes often feature strong contrasts of light and shadow, creating a sense of drama and highlighting the contours of the land. He achieved significant popularity with these works, finding a ready market among the growing middle-class collectors of the Victorian era.

Success, Rivalry, and the Royal Academy

By the mid-19th century, John Linnell was one of the most commercially successful landscape painters in Britain, rivaling even the great J.M.W. Turner in terms of the prices his works commanded. He amassed considerable wealth through the sale of his paintings, enabling him to live comfortably and support his large family. His detailed, often dramatic, and recognizably English scenes appealed strongly to Victorian tastes.

Despite this success, Linnell maintained a fraught relationship with the Royal Academy of Arts. Although he exhibited there regularly for decades, he was repeatedly passed over for election as a full Academician (RA). The reasons for this remain debated but likely involved a combination of factors: his independent, sometimes abrasive personality; his non-conformist religious beliefs; and perhaps artistic rivalries.

Most notably, Linnell had a difficult relationship with John Constable, another giant of English landscape painting. While their approaches to landscape shared a basis in natural observation, their styles and temperaments differed. There is evidence suggesting that Constable actively campaigned against Linnell's election to the RA, possibly spreading rumours or casting doubt on his character or originality. This rivalry highlights the competitive nature of the London art world at the time. Linnell eventually withdrew his name from consideration for RA membership, distancing himself from the institution. His popular success contrasted with this lack of official recognition from the Academy establishment, a situation shared by other popular artists like John Martin, known for his sublime, apocalyptic scenes.

Life in Redhill and Later Years

In 1851, seeking tranquility away from the bustle of London and perhaps disillusioned with the politics of the art world, Linnell moved his family to Redstone Wood, Redhill, in Surrey. He purchased land and built a substantial house, 'Redstone Wood', which included a studio and gallery space. Surrey provided him with ample subject matter, and he continued to paint prolifically for the next three decades.

His later landscapes often revisited familiar themes – harvest scenes, wooded paths, dramatic sunsets – sometimes executed with a broader handling of paint and a heightened sense of atmospheric effect, though some critics found them repetitive compared to his earlier work. Nevertheless, they remained popular with collectors. He continued to explore religious themes in works like The Eve of the Deluge and The Last Gleam before the Storm, reflecting his deep Baptist faith.

Linnell's family life was deeply intertwined with art. Three of his sons – James Thomas Linnell, William Linnell, and John Linnell Jr. – also became artists, working in styles influenced by their father. His daughter Hannah's marriage to Samuel Palmer, despite later difficulties, cemented his connection to that important figure. He maintained friendships with artists like Edward Thomas Daniell, a painter and etcher. Linnell remained active as an artist almost until his death at Redstone Wood on January 20, 1882, at the age of 89.

Engraving and Other Media

Beyond his significant output in oil painting, John Linnell was also a highly accomplished engraver and worked proficiently in watercolour. His skill in engraving was evident not only in the plates he produced for William Blake's Book of Job but also in his own original prints and reproductions of his paintings and portraits. Engraving required precision and control, qualities that mirrored the detailed nature of much of his painted work.

His watercolour sketches and finished works demonstrate a sensitivity to the medium's transparency and fluidity. Like many artists of his generation, he used watercolour for preparatory studies made outdoors, capturing fleeting effects of light and weather that could inform his larger oil paintings executed in the studio. These watercolours often possess a freshness and immediacy that complements his more finished oils. He was also skilled in miniature painting, particularly earlier in his career, showcasing his versatility across different scales and techniques.

Legacy and Re-evaluation

Following his death, John Linnell's reputation experienced a period of relative decline, overshadowed by the enduring fame of contemporaries like Turner and Constable, and the later rise of movements like Impressionism. His detailed naturalism and sometimes overtly religious or sentimental themes fell out of favour with modernist sensibilities.

However, the later 20th century saw a significant re-evaluation of his work. Exhibitions and scholarly research shed new light on his technical skill, his unique vision of the English landscape, and his crucial role as a supporter of William Blake. Art historians began to appreciate the intensity of his observation, the psychological depth in his portraits, and the atmospheric power of his landscapes. Some commentators even noted proto-Surrealist qualities in the heightened reality and meticulous detail of works like Kensington Gravel Pits.

Today, John Linnell is recognized as a major figure in 19th-century British art. His work is held in numerous public collections, including the Tate Britain, the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., and the Art Institute of Chicago. He is remembered not only for his own artistic achievements but also for his vital support of Blake and his connection to the visionary circle of 'The Ancients'. His dedication to capturing the specific character and spiritual resonance of the English landscape secured his place in the history of art.

Conclusion

John Linnell's long career spanned a transformative period in British art. From his early training and success in portraiture to his emergence as a leading landscape painter, he forged a distinctive path marked by meticulous naturalism, dramatic intensity, and often profound spiritual undertones. His complex relationship with the Royal Academy and his rivalry with Constable add layers to his story, while his unwavering support for William Blake remains one of his most enduring legacies. As a painter, engraver, and influential figure within his artistic community, Linnell captured the fields, skies, and woods of England with a unique vision, leaving behind a body of work that continues to be studied and admired for its technical brilliance and evocative power. He stands as a testament to the diverse expressions of Romanticism and Naturalism in 19th-century Britain.