Introduction: A Master of Transition

Duccio di Buoninsegna stands as a colossus in the history of Italian art, a pivotal figure whose work embodies the transition from the stylized conventions of Byzantine art to the burgeoning naturalism and emotional depth that would characterize the Renaissance. Active primarily in Siena during the late 13th and early 14th centuries, Duccio is widely regarded as the father of the Sienese School of painting. His profound influence shaped the artistic identity of his city and resonated throughout Italy, leaving an indelible mark on the course of Western art. His ability to synthesize tradition with innovation created a unique visual language, rich in decorative beauty and imbued with a gentle, human spirituality.

Through his masterful use of color, line, and composition, Duccio endowed traditional religious subjects with unprecedented grace and feeling. His workshop became a training ground for a generation of artists, ensuring the continuation of his stylistic legacy. While his Florentine contemporary, Giotto, was forging a path towards monumental realism, Duccio cultivated a distinct Sienese aesthetic characterized by lyrical elegance, intricate detail, and a radiant palette, often enhanced by the lavish use of gold leaf. Understanding Duccio is key to understanding the artistic flourishing of Siena in the period leading up to the Renaissance.

Siena's Son: Early Life and Artistic Context

Pinpointing the exact details of Duccio di Buoninsegna's life remains a challenge for art historians, as documentary evidence is scarce. However, based on existing records, it is generally accepted that he was born in Siena, likely sometime between 1255 and 1260. His death is similarly estimated to have occurred around 1318 or 1319. He appears to have spent the vast majority of his life and career in his native city, a thriving and fiercely independent republic that rivaled Florence in wealth, power, and artistic ambition during this period.

Siena provided a fertile ground for artistic development. The city was deeply devoted to the Virgin Mary, who was considered its celestial protector. This civic piety fueled numerous commissions for religious art, particularly depictions of the Madonna and Child. Artistically, Siena, like much of Italy, was still heavily influenced by the Byzantine tradition, characterized by its hierarchical compositions, elongated figures, and use of gold backgrounds to signify a divine realm. However, the late 13th century also saw the influx of Gothic influences from Northern Europe, bringing a new emphasis on linear grace, emotional expression, and narrative detail. Duccio emerged within this dynamic context, absorbing these diverse currents while forging his own unique path. Early Sienese painters like Guido da Siena and the Florentine-born Coppo di Marcovaldo, who was active in Siena, likely provided foundational influences.

Forging a New Vision: Artistic Development and Style

Duccio's genius lay in his ability to respectfully engage with the dominant Byzantine style while simultaneously infusing it with new life and sensitivity drawn from Gothic art and his own observations. He retained elements of the Byzantine tradition, such as the use of rich color, gold leaf backgrounds, and certain iconographic conventions. However, he softened the rigid linearity and hieratic formality often associated with Byzantine art. His figures possess a greater sense of volume, their draperies fall in more naturalistic folds, and their interactions convey a more palpable human tenderness.

The influence of French Gothic art is evident in the elegant, flowing lines of his figures and the delicate emotional expressiveness he achieved. Unlike the starker, more sculptural forms favored by Cimabue and Giotto in Florence, Duccio's figures often exhibit a gentle sway and refined grace. He was a master storyteller, capable of arranging complex narrative scenes with clarity and decorative appeal. His use of color was sophisticated, employing subtle modulations and harmonies to create mood and define form.

Furthermore, Duccio began experimenting with representing space and architecture in a more convincing, albeit still intuitive, manner than his predecessors. While not employing the systematic perspective developed later in the Renaissance, he placed his figures within architectural settings that provided a greater sense of depth and context for the narrative unfolding. This combination of Byzantine richness, Gothic elegance, and burgeoning naturalism created a style that was both deeply spiritual and visually captivating, perfectly suited to the tastes and devotional needs of his Sienese patrons. His primary medium was egg tempera on wood panel, a demanding technique that he mastered, achieving remarkable luminosity and detail.

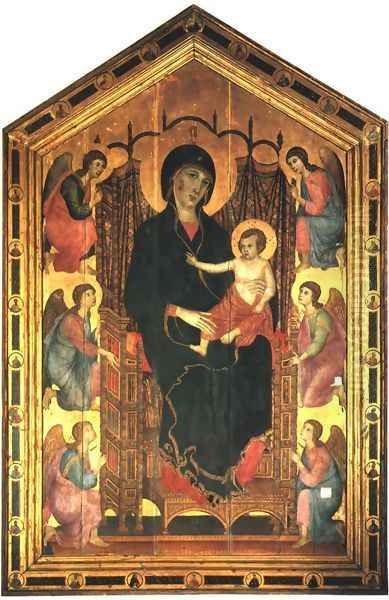

Early Triumphs: The Rucellai Madonna

One of Duccio's earliest documented and most significant works is the large panel painting known as the Rucellai Madonna. Commissioned in 1285 by the Compagnia dei Laudesi, a lay confraternity associated with the Dominican church of Santa Maria Novella in Florence, this work marked a major achievement. For centuries, it was mistakenly attributed to the Florentine master Cimabue, a testament to its quality and the stylistic dialogues occurring between Sienese and Florentine artists. Its correct attribution to Duccio solidified his reputation as a leading master even beyond Siena.

The Rucellai Madonna depicts the Virgin Mary enthroned, holding the Christ Child and surrounded by six kneeling angels. While retaining the majestic scale and gold background typical of Byzantine icons, Duccio introduced significant innovations. The Virgin's throne is rendered with a greater attempt at three-dimensionality, creating a more believable space. The angels, though symmetrically arranged, possess individuality in their poses and expressions. Most notably, the Virgin's face exhibits a softer modeling and a more gentle, human expression than seen in earlier works. The drapery, particularly the delicate gold striations on Mary's mantle, showcases Duccio's mastery of line and decorative effect. This commission in Florence highlights Duccio's growing fame and his ability to compete with the leading artists of the day.

The Metropolitan Madonna and Other Works

Around 1300, Duccio painted a smaller, more intimate panel known as the Madonna and Child, now housed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. This work, possibly intended for private devotion, further exemplifies Duccio's evolving style. Here, the interaction between Mother and Child is imbued with remarkable tenderness. The Christ Child gently pushes away the Virgin's veil, his gaze meeting hers with poignant intensity. The Virgin looks out, not directly at the viewer, but with a melancholic expression, perhaps contemplating her son's future sacrifice.

The delicate modeling of the faces, the soft folds of the drapery, and the intricate gold tooling on the halos and borders are characteristic of Duccio's mature style. The parapet in the foreground adds a sense of spatial depth, creating a more immediate connection between the sacred figures and the viewer. Works like this demonstrate Duccio's ability to convey profound religious feeling through subtle human gestures and expressions, moving beyond the hieratic formality of earlier traditions. Other fragments and smaller panels attributed to Duccio or his workshop survive, showcasing his consistent quality and the demand for his work.

The Crowning Achievement: The Maestà Altarpiece

Duccio's undisputed masterpiece, and one of the seminal works of early Italian painting, is the magnificent Maestà (Majesty) altarpiece, commissioned in 1308 for the high altar of Siena Cathedral. This monumental undertaking occupied Duccio and his workshop for three years, culminating in its completion in 1311. The contract stipulated that Duccio paint it with his own hands and work on it continuously in Siena. The city recognized the significance of this commission, awarding Duccio an exceptionally large fee, reportedly 3000 gold florins, though records indicate payments were complex and involved advances and reimbursements.

The Maestà was a vast, double-sided polyptych, painted in tempera and gold leaf on wood panels. The front, facing the congregation, was dominated by a large central scene of the Virgin and Child enthroned in majesty, surrounded by a celestial court of angels and saints, including the four patron saints of Siena kneeling in the foreground (St. Ansanus, St. Savinus, St. Crescentius, and St. Victor). Above and below this central panel were smaller scenes depicting the infancy of Christ and the last days of the Virgin, as well as figures of prophets and apostles. The sheer scale and complexity of the composition, populated by dozens of figures rendered with individual care, were unprecedented.

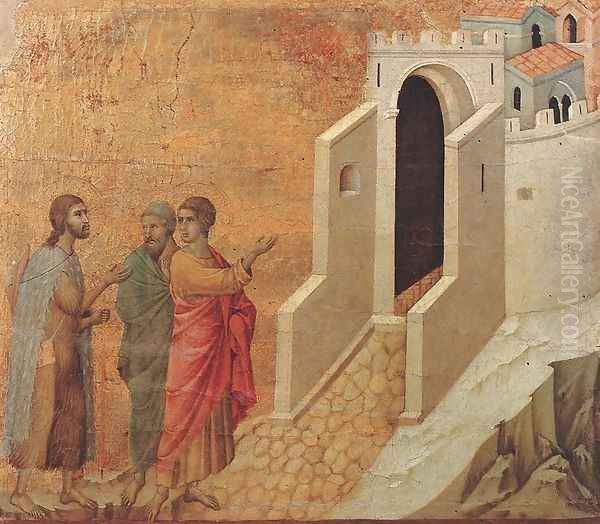

The reverse side of the Maestà, facing the clergy in the choir, featured an extensive narrative cycle of twenty-six scenes depicting the Passion of Christ, beginning with the Entry into Jerusalem and culminating in the appearances after the Resurrection. These smaller panels demonstrate Duccio's remarkable skill as a narrative painter. He arranged the figures and architectural elements to convey the drama and emotion of each episode with clarity and elegance. Scenes like the Betrayal of Christ, the Crucifixion, and the Road to Emmaus are rendered with psychological insight and compositional ingenuity.

A Civic Celebration: The Procession of the Maestà

The completion of the Maestà was met with extraordinary civic pride and celebration in Siena. Contemporary accounts describe the momentous occasion on June 9, 1311, when the altarpiece was transported from Duccio's workshop near the Porta Stalloreggi to the Cathedral. Businesses closed, and the Bishop led a great procession of city officials, clergy, and citizens through the streets. Bells rang, trumpets played, and prayers were offered as the magnificent artwork, Siena's tribute to its protector, the Virgin Mary, was carried in triumph to its place of honor on the high altar.

This event underscores the deep integration of art, religion, and civic life in late medieval Siena. The Maestà was not merely a devotional object; it was a symbol of the city's identity, piety, and artistic prowess. Its installation was a unifying moment for the community, reflecting the immense value placed on Duccio's achievement. The altarpiece remained in place for nearly two centuries, a focal point of worship and a testament to Siena's golden age.

Dismantling and Dispersal

Unfortunately, the Maestà did not survive intact. In 1771, driven by changing tastes and liturgical practices, the massive structure was dismantled. The panels were sawn apart, and the wooden framework was discarded. While the main front panel and many of the narrative scenes remained in Siena (now housed in the Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, adjacent to the Cathedral), other smaller panels from the predella (base) and the upper sections were dispersed over time.

Today, these precious fragments are scattered among various museums and private collections around the world. Notable examples include The Annunciation and The Assumption of the Virgin in the National Gallery, London; The Nativity with the Prophets Isaiah and Ezekiel and The Temptation of Christ on the Mountain in the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.; and The Temptation of Christ in the Frick Collection, New York. While its original unified impact is lost, the surviving panels continue to testify to Duccio's extraordinary skill and the altarpiece's original splendor. Art historians continue to study these fragments, piecing together the original arrangement and appreciating the narrative and artistic coherence of the whole.

Life Beyond the Studio: Fines and Finances

While Duccio's artistic reputation was stellar, surviving documents paint a picture of a man whose personal life was not without its complexities and troubles. Archival records reveal a surprising number of fines levied against him for various offenses. These included debts, refusal to swear allegiance to certain officials, failure to perform military duties, and even an intriguing, though likely minor, charge related to sorcery or alchemy ("arte magica").

These infractions should perhaps be viewed within the context of a litigious society and the often-precarious financial situation of artists, even successful ones. Despite these documented troubles and fines, the Sienese authorities clearly valued Duccio's artistic contributions immensely, as evidenced by the prestigious and lucrative commission for the Maestà. He was married and had seven children, indicating a family life alongside his demanding career. Records also show him purchasing property, such as a house and a vineyard, suggesting periods of financial stability, although later documents indicate renewed struggles with debt towards the end of his life. These fragments offer a tantalizing, if incomplete, glimpse into the human side of the great master.

The Sienese Legacy: Influence and Followers

Duccio's impact on the art of Siena was immediate and profound. He is rightly called the founder of the Sienese School, establishing a stylistic direction that would dominate the city's art for much of the 14th century. His workshop was likely large and active, training numerous assistants and followers who absorbed his techniques and aesthetic principles. Among his most direct followers were artists like Segna di Bonaventura (possibly his nephew), Ugolino di Nerio, and various anonymous masters identified by their works, such as the Master of Badia a Isola and the Master of Città di Castello.

These artists continued Duccio's emphasis on linear grace, rich color, and expressive detail. However, the next generation of Sienese masters, while deeply indebted to Duccio, developed their own distinct styles. Simone Martini, perhaps Duccio's greatest pupil (though direct tutelage is debated), adapted Duccio's elegance into a more courtly, refined Gothic style, achieving international fame. The brothers Pietro Lorenzetti and Ambrogio Lorenzetti built upon Duccio's narrative skills and spatial experiments, introducing greater naturalism, emotional drama, and complex allegorical themes, as seen in Ambrogio's famous frescoes of Good and Bad Government in Siena's Palazzo Pubblico.

While Duccio's lyrical and decorative style contrasted with the more volumetric and naturalistic path being forged by Giotto in Florence, his influence was not strictly confined to Siena. His work was known and respected in Florence, as the Rucellai Madonna commission demonstrates. Both Duccio and Giotto represent crucial departures from the Byzantine tradition, paving the way for the Renaissance, albeit through different stylistic emphases. Duccio's legacy lies in his creation of a uniquely Sienese voice in Italian art, one characterized by aristocratic elegance, devotional intensity, and exquisite craftsmanship. Other significant figures in this artistic milieu include the aforementioned Cimabue, who also bridged Byzantine and emerging styles, and later Sienese artists who continued to feel Duccio's influence.

Conclusion: An Enduring Majesty

Duccio di Buoninsegna remains a pivotal figure in the narrative of European art. As the fountainhead of the Sienese School, he translated the spiritual intensity of the Byzantine tradition into a new visual language marked by Gothic elegance and a nascent humanism. His ability to convey deep emotion through graceful line and radiant color, combined with his sophisticated narrative skills, set a standard for Sienese painting that endured for generations.

His masterpiece, the Maestà, even in its dismantled state, stands as one of the most important works of the late medieval period, a testament to both Duccio's genius and the civic and religious fervor of his native Siena. While perhaps sometimes overshadowed in popular accounts by his Florentine contemporary Giotto, Duccio's contribution was equally significant, offering a distinct and influential artistic vision. He masterfully blended decorative splendor with narrative clarity and emotional resonance, creating works that continue to inspire awe and devotion centuries later. Duccio truly captured the soul of Siena in its golden age, leaving behind a legacy of enduring majesty.