Bernard Karfiol stands as a distinctive, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the narrative of early 20th-century American modernism. An artist whose career bridged the academic traditions of the late 19th century with the burgeoning avant-garde movements of the new era, Karfiol forged a personal style characterized by its lyrical sensitivity, nuanced color palettes, and a profound appreciation for the human form and the natural landscape. Born in Budapest, Hungary, in 1886 to American parents, his life and art were shaped by experiences on both sides of the Atlantic, culminating in a body of work that, while rooted in American sensibilities, resonated with European modernist currents.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Though his birthplace was European, Bernard Karfiol's upbringing was quintessentially American. His family returned to the United States when he was young, settling in Brooklyn, New York. It was here that his artistic inclinations first manifested. Remarkably, by the tender age of thirteen, Karfiol was already enrolled at the prestigious Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, a testament to his precocious talent and serious commitment to art. This early immersion in formal art education provided him with a solid technical foundation.

His promise was further recognized when he received a scholarship to attend the National Academy of Design in New York. The Academy, at that time, was a bastion of traditional artistic values, emphasizing rigorous training in drawing and academic principles. While Karfiol absorbed these lessons, his artistic journey was destined to extend beyond the confines of American academicism. Like many ambitious young American artists of his generation, he felt the pull of Paris, then the undisputed capital of the art world.

The Parisian Crucible: Education and Encounters

Around 1901 or 1902, Karfiol made his way to Paris to continue his studies. He enrolled at the Académie Julian, a renowned private art school that attracted students from across the globe, including many Americans. The Académie Julian offered a more liberal alternative to the rigid École des Beaux-Arts and was known for its roster of influential instructors. Karfiol studied under Jean-Paul Laurens, a respected academic painter known for his historical and religious scenes. Under Laurens's tutelage, Karfiol would have further honed his skills in figure drawing and composition, remaining there until approximately 1906.

During his years in Paris, Karfiol was not solely confined to academic studies. He began to exhibit his work, participating in the Paris Salon in 1904 and the more progressive Salon d'Automne in 1905. The Salon d'Automne, in particular, was a key venue for emerging avant-garde art; it was famously the site of the Fauvist "scandal" in 1905, where artists like Henri Matisse and André Derain shocked the public with their bold use of color. Karfiol's participation indicates his early engagement with the contemporary art scene.

Paris in the early 1900s was a vibrant hub of artistic innovation. Karfiol had the invaluable opportunity to connect with some of the era's most influential figures. He became acquainted with Leo and Gertrude Stein, the American expatriate siblings whose apartment at 27 rue de Fleurus was a legendary gathering place for avant-garde artists and writers, including Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse. Exposure to their collection and the intellectual ferment of their circle would have been profoundly impactful.

Karfiol also formed connections with fellow artists. He knew the American painter Samuel Halpert, who was also part of the Parisian art scene. Perhaps one of his most intriguing acquaintances was with Henri Rousseau, the self-taught "primitive" painter whose unique vision captivated many modern artists. Rousseau's directness and imaginative compositions offered a compelling counterpoint to academic art, and his influence was felt by many, including Picasso. Karfiol's interaction with such diverse artistic personalities broadened his perspectives.

An interesting, though less art-focused, aspect of his Parisian life was his ownership of a lingerie shop in an exclusive part of the city. This venture suggests a practical side to the artist, perhaps a means to support himself while pursuing his artistic passions. It also hints at a certain entrepreneurial spirit. One anecdote from this period involves him warmly hosting a friend named Sal, offering him lunch at his "mansion" and even financial assistance, which Sal declined, suggesting the money be sent to Karfiol's cousin in Poland. This reveals a generous and hospitable nature.

Return to America and Early Career

After several formative years in France, Karfiol returned to the United States, settling in New York. The American art scene he returned to was on the cusp of significant change but had not yet fully embraced European modernism. Immediate success was not forthcoming for Karfiol. To supplement his income, he took up teaching, a common path for artists, from approximately 1908 to 1913. This period was likely one of continued artistic development and search for his unique voice, away from the direct stimuli of Paris.

His early work from this period began to show a synthesis of his academic training and his exposure to modern European art. He focused primarily on painting, with a particular interest in figure studies, portraits of children, and nudes. These subjects would remain central to his oeuvre throughout his career, allowing him to explore form, color, and emotional expression.

The Armory Show: A Turning Point

A pivotal moment for Karfiol, as for many American artists, was the International Exhibition of Modern Art, better known as the Armory Show, held in New York City in 1913. This landmark exhibition introduced a broad American audience to the radical developments in European art, showcasing works by artists like Marcel Duchamp, Constantin Brâncuși, Francis Picabia, Wassily Kandinsky, and the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists. Organized by American artists such as Arthur B. Davies, Walt Kuhn, and Walter Pach, the show was a sensation, provoking both outrage and excitement.

Karfiol was among the American artists whose work was included in the Armory Show. This exposure proved crucial for his career. It was here that his art caught the attention of Hamilton Easter Field, an influential artist, critic, teacher, and publisher. Field became an important patron and supporter of Karfiol, providing encouragement and helping to bring his work to a wider audience. Field was also instrumental in establishing the Ogunquit art colony in Maine, a place that would later become significant for Karfiol. This patronage marked the beginning of Karfiol's ascent in the American art world.

Developing a Signature Style: Influences and Themes

Following the Armory Show, Karfiol's career began to gain momentum. His artistic style continued to evolve, characterized by a gentle modernism that eschewed radical abstraction in favor of a more lyrical and representational approach. He demonstrated a remarkable sensitivity to color, often employing a palette that was both rich and subtle. His compositions were typically well-balanced and harmonious, reflecting his strong academic grounding, yet infused with a modern sensibility in their simplification of forms and expressive brushwork.

A significant influence on Karfiol's work was American folk art. In the 1910s and 1920s, there was a growing interest among modernist artists in folk traditions, valued for their directness, unpretentiousness, and intuitive design. Karfiol, along with his good friend, the sculptor Robert Laurent, became an avid collector of folk art and antiques, particularly during their summers in Ogunquit, Maine. This interest is reflected in the simplicity and sincerity of Karfiol's own paintings, which sometimes evoke the charm and unstudied grace of folk portraiture or genre scenes.

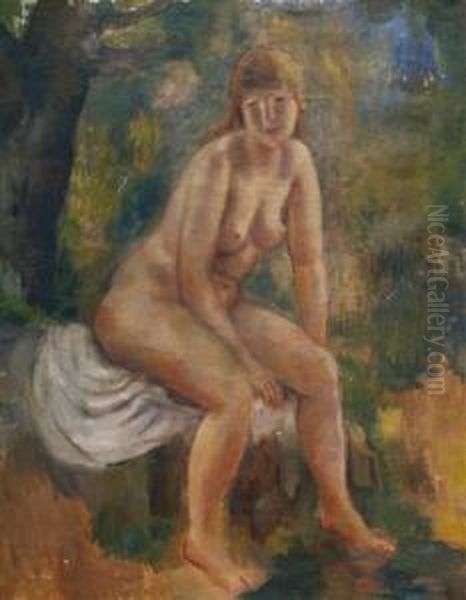

His subject matter remained focused on the human figure and landscapes. Nudes were a recurring theme, rendered with a sensuousness and intimacy that recalled artists like Auguste Renoir, yet filtered through a modern lens. His nudes often possess a quiet monumentality and a palpable sense of presence. Seated Nude (1929), now in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York, is a prime example, showcasing his mastery of form, subtle color harmonies, and tender observation. The figure is solid and sculptural, yet imbued with a soft, almost melancholic introspection.

Children were another favored subject. Karfiol depicted them with empathy and without sentimentality, capturing their naturalness and individual personalities. These portraits, like his "Miss B. N." series, often highlight his skill in conveying character through subtle nuances of expression and posture.

Ogunquit, Maine: A Source of Inspiration

The coastal village of Ogunquit, Maine, became an important artistic haven for Karfiol, as it did for many other American artists, including Marsden Hartley, Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Edward Hopper, and George Bellows. Hamilton Easter Field had established an art school and colony there, and Karfiol became a regular summer resident. The rugged Maine landscape, with its rocky coastline, pine forests, and clear light, provided a rich source of inspiration for his landscape paintings.

His Maine landscapes are characterized by their serene beauty and a deep connection to place. He often depicted tranquil scenes, imbued with a sense of timelessness. It was also in Ogunquit that his engagement with folk art deepened, alongside Robert Laurent. They scoured the region for antiques and vernacular art, activities that undoubtedly informed their own creative practices. Laurent, known for his elegant sculptures, also shared an interest in depicting children, creating a thematic link with Karfiol's work.

One of Karfiol's notable works from this period is Making Music (circa 1920), which is in the collection of the American Folk Art Museum. This painting, likely set in Ogunquit, depicts figures playing musical instruments in an interior setting. It exemplifies his ability to create harmonious compositions, his warm color sense, and the gentle, almost idyllic mood that pervades much of his work. The figures are rendered with a simplified solidity that hints at the influence of artists like Paul Cézanne, yet retains Karfiol's distinctive lyrical touch.

Artistic Circle and Recognition

Throughout the 1920s and beyond, Karfiol's reputation grew. He continued to associate with a circle of prominent artists. In 1926, he traveled to Paris with Samuel Halpert, and they spent the summer together in Ogunquit, Maine, along with other artists like Stefan Hirsch and Walt Kuhn. These interactions and shared experiences fostered a supportive artistic community.

Karfiol's connection with younger artists is evidenced by his invitation to Milton Avery to participate in a group exhibition at the Opportunity Gallery in New York in 1928. Avery, who would go on to become a highly influential figure in American color field painting, was at that time still developing his style. Karfiol's recognition of his talent demonstrates his engagement with the evolving art scene.

His work began to be handled by the respected art dealer Joseph Brummer, who organized several solo exhibitions for Karfiol between 1923 and 1927. These shows helped to solidify his standing and brought his art to the attention of collectors and museums. His paintings started entering important public collections, and he received accolades for his work, including the prestigious First William A. Clark Prize from the Corcoran Gallery of Art and an honorable mention in the Anto Carington award.

Karfiol's Artistic Style in Depth

Bernard Karfiol's art is often described as a form of "intimate modernism." He was not an artistic revolutionary in the vein of the European cubists or surrealists, nor did he align himself with the more abstract tendencies emerging in American art. Instead, he carved out a niche for himself by creating works that were modern in their sensibility but remained committed to representation and traditional genres like the nude, the portrait, and the landscape.

His style is characterized by several key elements:

1. Lyrical Quality: There is a poetic and often gentle mood in his paintings. His figures, whether nudes or children, are often depicted in moments of quiet contemplation, imbued with a sense of inner life.

2. Color Harmony: Karfiol was a sophisticated colorist. His palettes could range from muted and subtle to rich and vibrant, but they were always harmoniously orchestrated. He had a particular fondness for warm earth tones, soft blues, and gentle pinks, often juxtaposed to create a pleasing visual rhythm.

3. Simplified Forms: While his figures are clearly recognizable and anatomically sound (a legacy of his academic training), Karfiol often simplified forms, giving them a sense of solidity and volume. This simplification aligns him with modernist tendencies seen in artists like Cézanne or early Picasso.

4. Sensitive Brushwork: His application of paint was often delicate and nuanced, contributing to the overall sensitivity of his work. He could build up surfaces with subtle layers of color, creating a luminous effect.

5. Influence of Folk Art: The directness, sincerity, and unpretentious charm of American folk art are subtly woven into his sophisticated compositions, lending them a unique American flavor. This distinguishes him from many of his European-influenced contemporaries.

Artists like Pierre-Auguste Renoir, with his sensuous nudes and depictions of everyday life, or even Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, with his lyrical landscapes, might be seen as distant antecedents in terms of sensibility, though Karfiol's modernism is distinct. Among his American contemporaries, his work shares a certain quietude and focus on personal vision with artists like Preston Dickinson or Charles Demuth in his more figurative phases, though Karfiol's style remained more consistently representational and less overtly influenced by Cubism or Precisionism.

Later Career and Legacy

Bernard Karfiol continued to paint and exhibit throughout his life, maintaining his distinctive style even as American art moved towards Abstract Expressionism in the post-World War II era. He remained committed to his personal vision, focusing on the themes and subjects that had always resonated with him. While the art market in the 1930s and 1940s saw relatively modest prices for works by many American realists and figurative modernists, Karfiol's paintings were acquired by major institutions, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, and the Phillips Collection, in addition to MoMA and the American Folk Art Museum.

He passed away in 1952 in Irvington, New York, leaving behind a significant body of work that reflects a unique synthesis of European modernism and American sensibility. Historically, Karfiol might be seen as part of a generation of American artists who absorbed the lessons of European modernism but adapted them to an American context, often tempering avant-garde impulses with a respect for tradition and a focus on personal experience.

His art does not shout for attention; rather, it invites quiet contemplation. In a period marked by dramatic artistic upheavals and bold manifestos, Karfiol pursued a more introspective path. His contribution lies in the consistent quality and integrity of his work, his sensitive portrayal of the human form, and his lyrical interpretations of the American scene. He was a painter who found beauty in the everyday, in the quiet moments, and in the enduring connection between humanity and nature.

Conclusion: An Enduring, Gentle Modernist

Bernard Karfiol's legacy is that of an artist who successfully navigated the complex currents of early 20th-century art, creating a body of work that is both modern and timeless. His European training under figures like Jean-Paul Laurens, his exposure to the Parisian avant-garde through connections with the Steins and artists like Rousseau and Halpert, and his deep engagement with American life and landscape, particularly in Ogunquit alongside friends like Robert Laurent, all shaped his unique artistic vision.

His paintings, whether the serene nudes like Seated Nude, the charming genre scenes like Making Music, or his sensitive portraits of children, speak with a quiet eloquence. He was a master of subtle color and harmonious composition, infusing his work with a lyrical quality that continues to resonate. While perhaps not as radical as some of his contemporaries like Marsden Hartley or John Marin, Karfiol's gentle modernism holds an important place in the diverse tapestry of American art, representing a thoughtful and deeply personal response to the artistic challenges and opportunities of his time. His work remains a testament to the enduring power of sensitive observation and skilled craftsmanship in the creation of meaningful art.