Introduction

Utagawa Kuniyoshi , born in 1798 and passing away in 1861, stands as one of the towering figures of Japanese ukiyo-e, the art of "pictures of the floating world." Flourishing during the late Edo period, a time of cultural vibrancy and underlying societal change, Kuniyoshi carved a unique niche for himself through his powerful imagination, technical brilliance, and thematic diversity. While ukiyo-e is often associated with serene landscapes or elegant courtesans, Kuniyoshi infused the genre with unparalleled energy, drama, and often, a touch of the bizarre.

He was a master craftsman of the woodblock print, navigating the complex collaborative process involving designers, carvers, and printers to bring his visions to life. His subjects ranged widely, from ferocious warriors and legendary heroes drawn from Japanese and Chinese history, to captivating depictions of kabuki actors, beautiful women, eerie ghosts and monsters (yokai), charming landscapes, and surprisingly tender portrayals of animals, especially his beloved cats. Furthermore, he possessed a keen satirical wit, often embedding social commentary within seemingly innocuous scenes.

Kuniyoshi's influence extended far beyond his own lifetime. He was not only a prolific artist but also an influential teacher, nurturing a generation of talented pupils. His dynamic compositions and imaginative flair left an indelible mark on subsequent Japanese art forms, including modern manga and anime, and his work continues to be celebrated and studied worldwide for its artistic merit and cultural significance. He remains a pivotal figure in understanding the dynamism and creativity of late Edo-period Japan.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

Utagawa Kuniyoshi entered the world in 1798 in Edo (modern-day Tokyo), specifically in the Nihonbashi district, a bustling center of commerce and culture. Born Igusa Magosaburō, he was the son of a silk dyer, Yanagiya Kichiemon. This connection to the world of textiles and dyes might have provided an early exposure to patterns and colors, potentially nurturing his nascent artistic inclinations. Sources suggest he showed a natural talent for drawing from a young age.

A pivotal moment came around the age of 12 or 14, when his evident artistic promise caught the attention of a leading ukiyo-e master, Utagawa Toyokuni I (1769–1825). Toyokuni I was the head of the prestigious Utagawa school, the most dominant and commercially successful ukiyo-e school of the 19th century. Known for his powerful depictions of kabuki actors and beautiful women, Toyokuni I recognized the young boy's potential and accepted him into his studio as an apprentice.

Joining the Utagawa school was a significant step. Apprenticeship involved rigorous training, learning the fundamentals of drawing, design for woodblock printing, and the collaborative nature of the ukiyo-e production process. It also meant becoming part of a lineage and network. Within the studio, the young artist was given the art-name (gō) Kuniyoshi, incorporating the character "Kuni" from his master's name, a common practice signifying his place within the school's hierarchy. He would later also use art names like Ichiyūsai and Chōōrō.

Years of Struggle and the Path to Recognition

Despite graduating from his apprenticeship under Utagawa Toyokuni I around 1814 and beginning his independent career, Kuniyoshi initially faced considerable difficulty in establishing himself. The ukiyo-e world in Edo was highly competitive, dominated by established artists and trends. His early works, often focusing on actor prints (yakusha-e) in the style of his master, failed to gain significant traction or critical acclaim.

This period was marked by a stark contrast with the burgeoning success of some of his fellow Utagawa school artists, most notably Utagawa Kunisada (1786–1865), who later became Toyokuni III. Kunisada quickly gained popularity for his stylish depictions of kabuki actors and beautiful women, capturing the public's taste. Kuniyoshi, perhaps struggling to find his unique voice or lacking the right connections and commissions, found himself overshadowed.

Anecdotes from the period suggest that Kuniyoshi endured genuine financial hardship during these lean years. One famous story recounts that he was forced to supplement his income by repairing and selling used tatami floor mats, a far cry from the life of a successful artist. This experience of struggle, however, may have fueled his determination and pushed him to develop a more distinctive and powerful artistic style that would eventually set him apart. He continued to hone his skills, searching for subjects and approaches that resonated with his own temperament and the public's imagination.

The Breakthrough: Warriors of the Water Margin

Kuniyoshi's fortunes dramatically changed around 1827. He received a commission to illustrate a popular serialized adaptation of the classic Chinese novel Shuihu Zhuan, known in Japan as Suikoden. The series, titled Tsuzoku Suikoden goketsu hyakuhachinin no hitori (One of the 108 Heroes of the Popular Suikoden All Told), depicted the legendary outlaws and heroes of the original tale. This project proved to be the perfect vehicle for Kuniyoshi's burgeoning talent for dynamic action and dramatic storytelling.

He threw himself into the work, creating single-sheet prints of the individual heroes, each portrayed with incredible energy, intricate detail, and often, elaborate tattoos covering their bodies. These were not static portraits; Kuniyoshi depicted the heroes in moments of intense action, showcasing their superhuman strength, fierce determination, and rebellious spirit. The prints were an immediate and sensational success, captivating the Edo public.

The Suikoden series firmly established Kuniyoshi's reputation as a master of warrior prints (musha-e). His bold compositions, exaggerated musculature, and dramatic flair were unlike anything seen before in this scale and intensity. The series was so popular that it sparked a "Suikoden boom" in Edo. Beyond securing his fame and financial stability, the series had a lasting cultural impact: the vivid depictions of tattooed heroes are widely credited with popularizing large-scale, pictorial tattoos (irezumi) among the populace, particularly among firefighters and laborers who admired the heroes' bravery and defiance. Kuniyoshi had found his niche, and the world of ukiyo-e would never be the same.

Kuniyoshi's Distinctive Artistic Style

Utagawa Kuniyoshi developed an artistic style that was immediately recognizable for its power, dynamism, and imaginative scope. Central to his work was an unparalleled sense of energy. His figures rarely stand static; they leap, grapple, fight, and contort in dramatic poses, filling the picture plane with movement. This was achieved through bold, often diagonal compositions, foreshortening, and an intuitive understanding of how to convey action within the constraints of the woodblock print medium.

His use of line was strong and assertive, defining forms with clarity and vigor. This was complemented by a rich and often dramatic use of color. While adhering to the conventions of ukiyo-e printing, he employed vibrant hues and striking contrasts to heighten the emotional impact and visual appeal of his scenes. Intricate patterns, particularly in clothing and armor, added texture and detail, showcasing the incredible skill of the block carvers and printers he worked with.

A key aspect of Kuniyoshi's innovation was his incorporation, albeit sometimes subtle or stylized, of Western artistic techniques. He experimented with perspective to create a greater sense of depth than was traditional in Japanese art, and he utilized shading (chiaroscuro) to model figures and objects, giving them a more three-dimensional appearance. While not always anatomically perfect by Western academic standards, his figures often displayed an exaggerated musculature and dynamism that suggested an awareness of Western anatomical studies, possibly gleaned from imported Dutch books or prints (Rangaku).

Perhaps most defining was his seamless blend of realism and fantasy. Even when depicting historical or legendary figures, he imbued them with intense, believable emotions and physicality. Yet, he was equally adept at conjuring fantastical creatures, monstrous apparitions, and supernatural events with startling conviction. This fusion of the observed world with the boundless realms of imagination became a hallmark of his unique artistic vision.

A Universe of Subjects: Themes in Kuniyoshi's Art

While renowned for his warrior prints, Kuniyoshi's thematic range was remarkably broad, reflecting his versatile talent and restless imagination.

Warrior Prints (Musha-e): This remained a cornerstone of his output throughout his career. Beyond the iconic Suikoden series, he depicted countless scenes from Japanese history and legend. Famous samurai like Minamoto no Yoshitsune, Miyamoto Musashi, and figures from the Genpei War frequently appeared in his prints, often in the heat of battle or dramatic confrontations. His series Seichū gishi den (Stories of the Faithful Samurai), illustrating the tale of the 47 Rōnin (Chūshingura), was another popular success, celebrating themes of loyalty and honor.

Myths, Legends, and the Supernatural: Kuniyoshi possessed an extraordinary ability to visualize the unseen world. His prints teem with ghosts (yūrei), demons (oni), monsters (yokai), dragons, and other mythical creatures drawn from folklore and legend. One of his most famous works in this vein is the dramatic triptych Takiyasha the Witch and the Skeleton Spectre, depicting Princess Takiyasha summoning a giant skeleton. Another notable example is his depiction of the earth spider (Tsuchigumo) conjuring demons to haunt the hero Minamoto no Yorimitsu (Raiko), a print often interpreted as having satirical undertones.

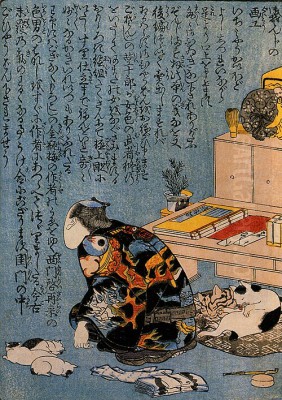

The World of Cats: Kuniyoshi was a well-known cat lover, reputedly keeping many cats in his studio. This affection translated into numerous delightful prints featuring felines. He depicted cats realistically in everyday settings, but more famously, he created anthropomorphic cats engaged in human activities – dressing in kimonos, performing kabuki roles, or forming characters in playful parodies (mitate-e). These cat prints showcase his humor and observational skills.

Beauties and Actors: Although his rival Kunisada dominated the market for prints of beautiful women (bijin-ga) and kabuki actors (yakusha-e), Kuniyoshi also produced notable works in these genres. His beauties often possess a strength and character distinct from Kunisada's more conventional elegance. His actor prints frequently captured moments of high drama from plays, emphasizing the emotional intensity of the performance.

Landscapes and Nature: While not as prolific in landscape as Hokusai or Hiroshige, Kuniyoshi created striking views of famous places in Japan, sometimes incorporating historical events or dramatic natural phenomena. His landscapes often retain the sense of dynamism found in his figurative work.

Humor and Satire (Giga): Kuniyoshi had a playful and often subversive sense of humor. He produced numerous caricatures (giga), puzzle pictures (hanji-e), and prints filled with witty observations or veiled social commentary. This satirical streak became particularly important during periods of government censorship.

Navigating Censorship: The Tenpō Reforms

The late Edo period saw increasing attempts by the Tokugawa shogunate to regulate public morals and control perceived extravagance. The Tenpō Reforms (Tenpō no kaikaku), enacted between 1841 and 1843 under the leadership of Mizuno Tadakuni, had a significant impact on the world of ukiyo-e publishing. These reforms aimed to enforce austerity and Confucian values, leading to strict censorship laws.

Among the targets were subjects deemed luxurious or morally questionable. Bans were placed on prints depicting kabuki actors (seen as promoting frivolous entertainment) and courtesans or geishas (considered symbols of decadence). This crackdown directly affected the livelihoods of many ukiyo-e artists, including Kuniyoshi, as actor and beauty prints were highly popular genres.

Kuniyoshi, ever resourceful, adapted his output to navigate these restrictions. While the bans were in effect, he shifted his focus towards subjects considered more acceptable, such as historical warrior prints (which could be framed as promoting martial virtues), landscapes, animal prints (especially his popular cats), and illustrations of didactic tales or legends, like the Kenjo reppu den (Stories of Wise and Heroic Women).

However, Kuniyoshi also employed his wit to subtly critique the reforms or comment on current events through satire and allegory. Prints that seemed to depict historical or legendary scenes could contain hidden references to contemporary figures or policies. For example, his famous print Minamoto no Yorimitsu in Bed, Haunted by the Earth Spider and Demons (circa 1843) has often been interpreted as a satirical allegory for the Shogun (represented by the ailing Yorimitsu) being troubled by monstrous forces (representing the failures or unpopularity of the Tenpō Reforms). His playful cat prints, by anthropomorphizing animals, could also serve as vehicles for gentle social commentary, bypassing the direct depiction of forbidden human subjects. This period highlights Kuniyoshi's ingenuity and his ability to maintain his creative voice even under duress.

Rivals and Contemporaries: The Edo Art World

Kuniyoshi operated within a vibrant and competitive artistic milieu in Edo. His primary relationship within the Utagawa school was with his master, Utagawa Toyokuni I, whose style influenced his early work, particularly in actor prints. Toyokuni I's emphasis on dramatic poses and expressive figures provided a foundation upon which Kuniyoshi would build his own unique vision.

His most significant peer relationship was undoubtedly with Utagawa Kunisada (later Toyokuni III). As fellow students under Toyokuni I, they experienced a complex dynamic of rivalry and mutual respect throughout their long careers. Kunisada achieved fame earlier and became the most commercially successful ukiyo-e artist of his time, particularly renowned for his prolific output of elegant actor prints and fashionable beauties. Kuniyoshi, while respecting Kunisada's success, reportedly felt himself to be the more artistically gifted, particularly in terms of imagination and dynamic composition. This rivalry likely spurred both artists to push their creative boundaries. Despite their differing strengths and target audiences, they occasionally collaborated on print series, demonstrating a professional collegiality.

Beyond the Utagawa school, Kuniyoshi was aware of and responded to the work of other major ukiyo-e figures. Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858), another Utagawa artist though not a direct student of Toyokuni I in the same way, rose to prominence slightly later with his revolutionary landscape prints, such as the Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō. While their primary subjects differed, both Kuniyoshi and Hiroshige contributed significantly to the diversification of ukiyo-e themes in the 19th century.

The towering figure of Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849), though belonging to a different school (Katsukawa, later independent), was an older contemporary whose innovative compositions and thematic breadth, including his famous Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, undoubtedly influenced the entire field. Kuniyoshi would have been keenly aware of Hokusai's artistic achievements. Another notable contemporary was Keisai Eisen (1790–1848), known for his distinctive and often decadent style of beauty prints (bijin-ga). Kuniyoshi also interacted closely with various publishers, such as Eijudō, who played a crucial role in commissioning, producing, and distributing his work.

The Kuniyoshi Workshop and His Students

Like most successful ukiyo-e masters, Kuniyoshi maintained an active studio, attracting numerous apprentices eager to learn his distinctive style and techniques. He was known as an influential teacher, guiding the development of many artists who would go on to make significant contributions to ukiyo-e and later Meiji-period art. His workshop was a hub of activity, producing designs for a wide array of prints.

Among his most prominent students was Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839–1892). Often considered Kuniyoshi's greatest successor, Yoshitoshi inherited his master's penchant for dramatic historical and legendary scenes, but developed his own intense, often psychologically charged style. Yoshitoshi became one of the last great masters of traditional ukiyo-e, bridging the gap between the Edo and Meiji eras.

Another significant figure associated with Kuniyoshi's studio, albeit perhaps briefly, was Kawanabe Kyōsai (1831–1889). Kyōsai, known for his wildly imaginative and often humorous or grotesque paintings and prints, initially studied with Kuniyoshi before moving on to the Kanō school of painting. However, Kuniyoshi's dynamic energy and penchant for the fantastic likely left an impression on him.

Other notable pupils who carried the "Yoshi" character from Kuniyoshi's name in their own art names include Utagawa Yoshiiku (1833–1904), known for his actor prints and sometimes gruesome scenes; Utagawa Yoshitora (active c. 1836–1887), who produced warrior prints and depictions of foreigners in Yokohama; Utagawa Yoshikazu (active c. 1848–1870), also known for warrior prints and Yokohama-e; and Utagawa Yoshifuji (1828–1887), who specialized in playful prints of children and toy prints (omocha-e). Further students included Utagawa Yoshimune II, Utagawa Yoshiume, and Utagawa Yoshitsuya, all contributing to the vast output associated with the Kuniyoshi lineage. Through his students, Kuniyoshi's artistic influence extended well into the latter half of the 19th century.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Utagawa Kuniyoshi remained artistically active throughout much of his later life, continuing to produce prints across his diverse range of subjects. His workshop flourished, and his reputation as a leading master of ukiyo-e was firmly cemented. He continued to explore historical narratives, legends, and his beloved cat themes, always bringing his characteristic energy and imagination to his work.

However, his health began to decline in his later years. A significant blow came with the Great Ansei Earthquake that struck Edo in 1855. While details are somewhat unclear, sources suggest that Kuniyoshi suffered from illness or possibly a stroke related to or exacerbated by the earthquake and its aftermath. This appears to have affected his ability to work, and his output likely decreased in the final years of his life.

Utagawa Kuniyoshi passed away on April 14, 1861, in Edo, the city whose vibrant culture he had captured so vividly in his art. He was buried at Dairinji Temple. His death marked the passing of one of the last great figures from the golden age of ukiyo-e.

His legacy, however, was immediate and lasting. He left behind an enormous body of work, estimated at thousands of print designs, which continued to be admired and collected. More importantly, he had trained a generation of artists, most notably Yoshitoshi, who would carry the torch of Japanese printmaking into the modern era. His innovative style and thematic explorations had irrevocably expanded the possibilities of the ukiyo-e medium.

Kuniyoshi's Influence Beyond Ukiyo-e

The impact of Utagawa Kuniyoshi's art resonates far beyond the traditional confines of the ukiyo-e print world. His students, particularly Tsukioka Yoshitoshi and Kawanabe Kyōsai, adapted elements of his dynamism and thematic interests into their own work during the Meiji Restoration, a period of rapid modernization and Westernization in Japan. They helped ensure that the spirit of ukiyo-e, infused with Kuniyoshi's energy, continued to evolve.

Perhaps Kuniyoshi's most visible legacy today lies in his profound influence on modern Japanese visual culture, specifically manga (comics) and anime (animation). His dramatic compositions, exaggerated action poses, expressive characters, and fascination with historical epics, martial arts, and supernatural fantasy find clear echoes in these popular contemporary forms. Many manga artists and animators implicitly or explicitly draw inspiration from the visual language pioneered by Kuniyoshi and other ukiyo-e masters. The energy, graphic impact, and storytelling techniques seen in his prints laid foundational groundwork for later narrative art.

Furthermore, Kuniyoshi's work, especially the Suikoden series with its heavily tattooed heroes, played a crucial role in the history and aesthetics of Japanese tattooing (irezumi). His designs provided a rich visual vocabulary for tattoo artists, and the popularity of his prints helped elevate tattooing from simple markings to elaborate pictorial body art, a tradition that continues today, though often associated with subcultures.

Kuniyoshi's prints also reached the West during the surge of Japonisme in the late 19th century. While artists like Hokusai and Hiroshige might be more famously associated with influencing Impressionist and Post-Impressionist painters, Kuniyoshi's works were also collected and admired in Europe and America. Figures like Claude Monet and Auguste Renoir were certainly exposed to the broader ukiyo-e aesthetic, which valued bold compositions, flattened perspectives, and decorative patterns – elements present in Kuniyoshi's work. His dramatic and imaginative scenes contributed to the Western fascination with Japanese art and culture.

Historical Assessment and Conclusion

In the grand narrative of Japanese art history, Utagawa Kuniyoshi is firmly established as one of the last and most brilliant masters of the ukiyo-e tradition. He emerged during a period when the art form was already highly developed, yet he managed to inject it with fresh vitality, unparalleled imagination, and technical innovation. His historical reputation rests on his extraordinary versatility, his mastery of dramatic composition, and his unique ability to blend realism with fantasy.

He is celebrated for pushing the boundaries of ukiyo-e, particularly through his dynamic warrior prints, which set a new standard for action and intensity. His explorations of myth, legend, and the supernatural remain captivating for their imaginative power and visual flair. Simultaneously, his humorous and satirical works, along with his charming depictions of cats, reveal a playful wit and keen observation of the world around him. His willingness to experiment with Western artistic conventions like perspective and shading, integrating them into a distinctly Japanese aesthetic, marks him as an innovative figure.

While sometimes overshadowed commercially during his lifetime by his rival Kunisada, and perhaps less known internationally than Hokusai or Hiroshige, Kuniyoshi's artistic stature has only grown over time. Scholars and collectors recognize the depth, power, and sheer creativity inherent in his vast body of work. He was not just a chronicler of the "floating world" but an artist who actively shaped its visual culture, capturing the energy, anxieties, and dreams of late Edo society. Utagawa Kuniyoshi's legacy endures through his captivating prints and his undeniable influence on subsequent generations of artists in Japan and beyond. He remains a testament to the enduring power of imagination and dramatic storytelling in visual art.