Utagawa Kunisada, born in 1786 in Edo (present-day Tokyo), Japan, stands as one of the most prolific, successful, and influential figures in the history of Japanese woodblock prints, known as ukiyo-e. His career spanned over six decades, witnessing the peak and eventual transformation of this popular art form during the late Edo period. Known for his vast output, particularly in the genres of actor prints (yakusha-e) and pictures of beautiful women (bijin-ga), Kunisada eventually inherited the prestigious name Toyokuni III, cementing his position as the leading master of the dominant Utagawa school. He passed away in 1865, leaving behind an immense body of work that captured the vibrant culture of his time.

His full original name was Sumida Shōgorō IX (角田庄五郎), though he is often referred to by his initial art name, Kunisada (国貞). In 1844, he formally adopted the name Toyokuni, becoming the third artist to bear this title, following his master Toyokuni I and his master's immediate successor, Toyoshige (Toyokuni II). Throughout his long career, Kunisada also employed various other art names (known as gō), including Gogotei (五渡亭), Kōchōrō (香蝶楼), and Ichiyūsai (一雄斎). These names often signified different periods or specific types of work within his extensive oeuvre. His birth name, sometimes cited as Shōzō (歌川庄藏), might have been another personal name or alias used during his life.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

Kunisada was born into a relatively prosperous family in Honjo, an eastern district of Edo. His family owned a licensed ferry service, the Tatekawa ferry, a position that provided a degree of stability uncommon for many aspiring artists of the time. His father, who was also an amateur poet, passed away when Kunisada was young. Despite this, the young boy showed a remarkable aptitude for drawing and painting from an early age. Recognizing his talent, his family supported his artistic inclinations.

Around the turn of the century, likely in 1800 or 1801, the young Sumida Shōgorō was accepted as an apprentice by the leading ukiyo-e master of the day, Utagawa Toyokuni I (1769-1825). Toyokuni I was renowned for his powerful actor portraits and elegant depictions of beauties, establishing a style that would define the Utagawa school for generations. Under Toyokuni's tutelage, the young artist learned the intricate process of designing woodblock prints, from initial sketches to the final color designs provided to the block carvers and printers.

Following tradition, he received an art name derived from his master's. Combining the "Kuni" (国) from Toyokuni with "Sada" (貞), possibly derived from a part of his personal name or another source, he became Utagawa Kunisada. His earliest known works date from around 1807, initially consisting of illustrations for popular novels (kusazōshi). By 1808 and 1809, he began producing full-color single-sheet prints, primarily focusing on the subjects that would become his forte: Kabuki actors and beautiful women.

Rise to Prominence and Early Style

Kunisada quickly established himself as a talented and versatile artist. His early works clearly show the influence of his master, Toyokuni I, particularly in the depiction of figures with elongated faces and somewhat stylized features. However, Kunisada soon developed his own distinct approach, characterized by a greater sense of realism, finer linework, and a fresh, appealing quality, especially in his bijin-ga.

By the early 1810s, Kunisada's reputation was growing rapidly. Critics and connoisseurs of the time already considered him a major talent. Some contemporary accounts suggest that by around 1813, his skill in depicting beautiful women was seen as surpassing that of his master, Toyokuni I. He quickly became one of the most sought-after ukiyo-e artists in Edo, rivaling other established figures within the Utagawa school, such as Utagawa Kunimaru, and competing in the broader market against artists like Kikukawa Eizan (1787-1867) and Keisai Eisen (1790-1848), who were also known for their bijin-ga.

His rise coincided with a period of flourishing popular culture in Edo. The Kabuki theatre was immensely popular, and prints depicting famous actors in their signature roles were in high demand. Similarly, prints of fashionable courtesans and city beauties reflected the tastes and trends of the urban populace. Kunisada proved adept at capturing the dynamism of Kabuki and the allure of contemporary women, making his prints highly desirable. His early success laid the foundation for a career marked by extraordinary productivity and commercial success.

Master of Actor Prints (Yakusha-e)

![[praise To The Four Seasons] by Gototei Kunisada](https://www.niceartgallery.com/imgs/2423826/m/gototei-kunisada-praise-to-the-four-seasons-45dcf018.jpg)

Throughout his career, Kunisada remained a dominant force in the field of yakusha-e. Following the tradition established by his master Toyokuni I, he produced thousands of prints depicting Kabuki actors, both in specific roles (onnagata female roles, heroic aragoto styles, romantic wagoto parts) and in off-stage portraits. His actor prints are noted for their dramatic compositions, expressive faces, and detailed rendering of costumes and props.

Kunisada captured the larger-than-life presence of Kabuki stars like Ichikawa Danjūrō VII (1791-1859) and Ichikawa Danjūrō VIII (1823-1854), Bandō Mitsugorō III (1775-1831), and Iwai Hanshirō V (1776-1847). He often depicted actors in close-up bust portraits (ōkubi-e), allowing for intense psychological portrayal, or in full-length figures striking dramatic poses (mie) characteristic of the Kabuki stage.

His style in actor prints evolved over time. While early works adhered closely to Toyokuni I's model, his later prints, especially those produced under the name Toyokuni III, often featured bolder lines, more vibrant colors (including the newly available Prussian blue), and increasingly elaborate designs. He frequently created multi-sheet compositions (diptychs, triptychs) to depict complex stage scenes involving multiple actors, showcasing his skill in composition and narrative. The sheer volume and consistent quality of his actor prints ensured his place as the leading yakusha-e artist of his generation, eclipsing even talented contemporaries like Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1798-1861) in this specific genre, though Kuniyoshi excelled in warrior prints.

Depicting Feminine Beauty (Bijin-ga)

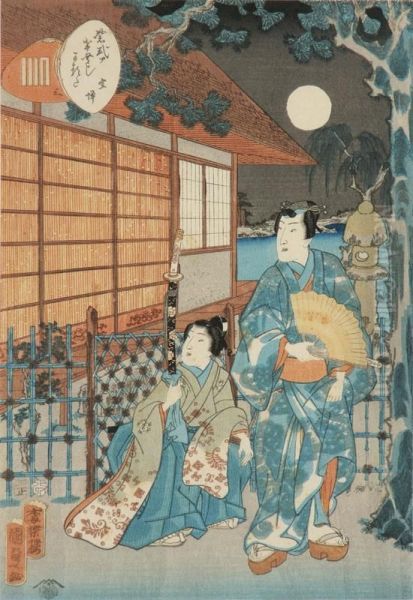

While renowned for his actor prints, Kunisada's bijin-ga were equally, if not more, celebrated, particularly in his early and middle career. He possessed a remarkable ability to capture the contemporary ideal of feminine beauty, often referred to as "iki" – a sophisticated blend of chic, allure, and understated elegance characteristic of Edo's urban culture. His women are typically portrayed with graceful postures, delicate features, and elaborate hairstyles and kimono, reflecting the latest fashions.

Kunisada's bijin-ga often depicted courtesans from the Yoshiwara pleasure district, geishas, waitresses, and ordinary townswomen engaged in daily activities or seasonal pastimes. He excelled at conveying subtle moods and emotions through nuanced facial expressions and body language. His series Tōsei Sanjūni Sō (Thirty-two Aspects of Women of the Present Day), produced in the 1820s, is a prime example of his mastery in this genre, showcasing different types of women and their characteristic charms.

He was sensitive to changing tastes and styles. His depiction of women evolved from the slender, elegant figures influenced by Toyokuni I and earlier masters like Kitagawa Utamaro (c. 1753-1806) and Torii Kiyonaga (1752-1815), towards more rounded, approachable figures in the 1820s and 1830s. Later in his career, particularly after adopting the Toyokuni III name, his female figures sometimes became more stylized, reflecting broader trends in late ukiyo-e. He often incorporated intricate patterns and rich colors, making full use of advanced printing techniques. His美人画 (bijin-ga) works, such as those simply titled Bijin-ga or specific series, remain highly valued for their aesthetic appeal and as documents of Edo period fashion and sensibility.

Versatility and Other Genres

While best known for actors and beauties, Kunisada's artistic output was remarkably diverse. He was a prolific book illustrator throughout his career, providing designs for numerous kusazōshi (popular illustrated fiction), gōkan (multi-volume novels), and poetry anthologies. His illustrations for the popular novel Nise Murasaki Inaka Genji (A Fake Murasaki and a Rural Genji), a parody of the classic Tale of Genji, were immensely successful and contributed significantly to the book's popularity in the 1830s and 1840s.

Kunisada also produced prints in various other genres. He designed sumō-e, dynamic prints of famous sumo wrestlers, capturing their power and bulk. Although less known for landscapes (fūkei-ga) than his famous contemporary Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858), Kunisada did produce landscape prints, often as backgrounds for figures or as part of collaborative series. Works like Eitai Bridge (永代橋) or Evening Snow at Bokuboji Temple (暮雪木母寺), likely part of larger series depicting famous places in Edo, showcase his ability in this area.

He also created historical and warrior prints (musha-e), though this genre was more strongly associated with his Utagawa school rival, Kuniyoshi. Additionally, like most ukiyo-e artists, he produced shunga (erotic prints), although these were often published anonymously due to censorship. His wide range extended to kachō-ga (bird-and-flower prints) and depictions of everyday life and customs, such as the Hot Spring Scene (温泉の図). This versatility demonstrated his comprehensive mastery of the ukiyo-e medium and his ability to cater to a wide range of popular tastes.

The Inheritance of Toyokuni III

The name "Toyokuni" carried immense prestige in the world of ukiyo-e. When Kunisada's master, Toyokuni I, died in 1825, his adopted son-in-law and student, Utagawa Toyoshige (1777-1835), took the name Toyokuni II. However, Toyoshige's claim to the name and his artistic output were considered by many, including Kunisada, to be less distinguished than that of the original Toyokuni.

In 1844, nearly a decade after Toyoshige's death, Kunisada made the significant move of adopting the Toyokuni name himself. He signed his works as "Toyokuni II," but later, asserting a direct lineage of talent from his master Toyokuni I, he began signing as Toyokuni III (三代豊国, Sandai Toyokuni). This act effectively bypassed Toyoshige's claim and positioned Kunisada as the true artistic successor to the great Toyokuni I and the undisputed head of the influential Utagawa school.

From 1844 onwards, most of his works bear signatures indicating Toyokuni III, often combined with his other art names like Kōchōrō or Ichiyūsai. This period marks the latter half of his career, during which he remained incredibly productive, running a large studio and overseeing the creation of thousands more prints. The adoption of the Toyokuni name solidified his status as the dominant figure in the ukiyo-e world of his time.

Collaborations and Artistic Relationships

The ukiyo-e world of the 19th century was interconnected, and collaborations between artists were common. Kunisada engaged in several notable collaborations, most famously with Utagawa Hiroshige. The two masters worked together on several series, where Kunisada typically designed the figures and Hiroshige contributed the landscape backgrounds. A well-known example is the Sōhitsu Gojūsantsugi (Paired Brushes Fifty-three Stations), a series depicting the Tōkaidō road, combining the strengths of both artists. They also collaborated on series depicting famous restaurants and scenic spots in Edo.

Kunisada also maintained complex relationships with other leading artists. Utagawa Kuniyoshi was his main rival within the Utagawa school. While both were students of Toyokuni I, they developed distinct styles and often competed for commissions, though they occasionally collaborated. Kunisada's focus remained largely on the popular genres of actors and beauties, while Kuniyoshi gained fame for his dramatic warrior prints, legends, and imaginative designs.

He also worked alongside his students. As the head of a large studio, particularly after becoming Toyokuni III, Kunisada oversaw the work of numerous pupils who assisted him in producing his vast output. Sometimes, prints designed primarily by students might bear his signature, a common practice at the time. His relationship with the older, highly individualistic master Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) was likely one of mutual respect mixed with professional rivalry, as they represented different approaches to ukiyo-e.

The Utagawa School and Kunisada's Legacy

As Toyokuni III, Kunisada presided over the Utagawa school during its period of greatest dominance. The school, founded by Utagawa Toyoharu (1735-1814) and brought to prominence by Toyokuni I, produced a vast number of artists who shaped the ukiyo-e landscape of the 19th century. Kunisada's studio was one of the largest and most productive, training numerous artists who carried on the Utagawa style.

Among his most important students were:

Utagawa Kunisada II (1823-1880): His son-in-law, who initially signed as Kunimasa III before inheriting the Kunisada name after his master's death, and later also used the name Toyokuni IV.

Utagawa Sadahide (c. 1807-1879): Known for his detailed Yokohama prints depicting foreigners and cityscapes, as well as warrior prints.

Toyohara Kunichika (1835-1900): Considered one of the last great masters of traditional yakusha-e, known for his bold compositions and dramatic actor portraits, bridging the Edo and Meiji periods.

Other pupils included artists like Utagawa Kunihisa II (1832-1891) and Utagawa Kuniteru III (1830-1874).

Through his own work and that of his students, Kunisada's influence extended well into the Meiji era (1868-1912), even as ukiyo-e faced challenges from new technologies like photography and lithography. His style, particularly in actor prints, set the standard for much of the latter half of the 19th century.

Social Context: Art in a Changing Era

Kunisada's long career unfolded against a backdrop of significant social and political change in Japan. The late Edo period saw increasing social tensions, economic difficulties including famines, and growing dissatisfaction with the Tokugawa shogunate's rule. Events like the Ōshio Heihachirō rebellion in Osaka (1837) reflected this underlying unrest. While ukiyo-e primarily depicted the "floating world" of pleasure and entertainment, the anxieties and changes of the era subtly permeated the art form.

The Tenpō Reforms (1841-1843) imposed strict censorship and sumptuary laws, attempting to curb perceived extravagance and moral decline. These reforms directly impacted ukiyo-e, restricting depictions of actors and courtesans, luxury goods, and politically sensitive subjects. Artists like Kunisada had to navigate these restrictions carefully. He sometimes used historical or legendary themes as allegories for contemporary events. An example is a triptych from 1843 depicting the hero Minamoto no Yorimitsu (Raikō) confronting the Earth Spider, which was interpreted as a satire of the shogunate and subsequently suppressed by the authorities. Despite censorship, Kunisada and his contemporaries found ways to continue producing popular prints, sometimes using clever symbolism or focusing on less controversial subjects.

Kunisada's work also reflected the growing cosmopolitanism of Edo. The limited trade with the Dutch and Chinese brought foreign goods and ideas into Japan. This is evident in the use of imported pigments like Prussian blue (bero-ai), which became popular in the 1820s and gave ukiyo-e prints a distinctive vibrant blue hue. Kunisada readily adopted this new pigment, using it extensively in his designs. His prints often meticulously documented the fashions, hairstyles, and accessories of the day, providing invaluable visual records of Edo culture.

Prolific Output, Reception, and Influence

Utagawa Kunisada was arguably the most prolific ukiyo-e artist of all time. Estimates suggest he designed between 20,000 and 25,000 individual prints over his career, encompassing single sheets, diptychs, triptychs, and illustrations for hundreds of books. This staggering output was made possible by his talent, work ethic, and the efficient operation of his large studio.

During his lifetime, Kunisada was immensely popular and commercially successful. His prints sold in large numbers, catering to the insatiable demand of the Edo populace for images of their favorite actors, beautiful women, and scenes from popular stories. He was, without doubt, the best-selling ukiyo-e artist of his time.

However, his critical reputation fluctuated after his death. During the Meiji era and much of the 20th century, Western collectors and some Japanese critics tended to favor earlier ukiyo-e masters like Utamaro, Sharaku (active 1794-1795), and Hokusai, sometimes dismissing Kunisada's work as overly commercial, repetitive, or lacking the perceived artistic depth of his predecessors or the dramatic flair of his rival Kuniyoshi. His sheer productivity sometimes worked against him, with the assumption that quantity must have compromised quality.

In recent decades, there has been a significant re-evaluation of Kunisada's work. Scholars and curators now recognize his technical skill, his keen observation of contemporary life, his role in shaping popular taste, and his importance as the central figure of mid-19th century ukiyo-e. His influence extended beyond Japan; European artists like Vincent van Gogh were avid collectors of Japanese prints, and Van Gogh himself owned a substantial number of works by Kunisada (the provided text mentions 159 prints), whose compositions and colors likely informed his own artistic development.

Conclusion: An Enduring Legacy

Utagawa Kunisada (Toyokuni III) dominated the world of Japanese woodblock prints for much of the mid-19th century. His unparalleled productivity, commercial success, and leadership of the influential Utagawa school made him the defining ukiyo-e artist of his era. While his critical fortunes have varied, his immense body of work remains a vibrant testament to the popular culture of late Edo Japan.

Through his masterful depictions of Kabuki actors, fashionable beauties, historical scenes, and contemporary life, Kunisada captured the essence of the "floating world" with remarkable skill and sensitivity. He navigated the challenges of censorship, adapted to changing tastes, and utilized new materials, all while maintaining an astonishing level of output. His collaborations with artists like Hiroshige, his rivalry with Kuniyoshi, and his mentorship of students like Kunisada II, Sadahide, and Kunichika further highlight his central role in the artistic networks of the time. Today, Kunisada is recognized not just for his popularity, but for his artistry, his historical significance, and his enduring contribution to the rich legacy of ukiyo-e.