Utagawa Kuniyoshi stands as one of the most dynamic, innovative, and beloved masters of Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock prints and paintings from the late Edo period. Born in 1798 and passing away in 1861, his life and career spanned a tumultuous era of social change, economic hardship, and burgeoning popular culture in Japan. Renowned for his depictions of valiant samurai, mythical heroes, terrifying monsters, and charmingly anthropomorphic cats, Kuniyoshi's work is characterized by its dramatic compositions, vibrant colors, unbridled imagination, and a rebellious spirit that often subtly challenged the authorities of his time. He was a pivotal figure in the Utagawa school, the dominant ukiyo-e institution of the 19th century, and his influence extended to his many pupils and continues to resonate in contemporary art forms.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Utagawa Kuniyoshi was born Igusa Yoshisaburō on January 1, 1798, in Nihonbashi, Edo (present-day Tokyo). His father, Yanagiya Kichiemon, was a silk dyer, and this early exposure to the world of design and color may have kindled young Yoshisaburō's artistic inclinations. From a young age, he demonstrated a precocious talent for drawing, reportedly impressing the renowned ukiyo-e master Utagawa Toyokuni I with his sketches at the tender age of twelve.

Around 1811, at approximately fourteen years old, Yoshisaburō was formally accepted into Toyokuni I's prestigious studio. This marked his entry into the Utagawa school, which was then the leading force in ukiyo-e production, particularly known for its actor prints (yakusha-e) and prints of beautiful women (bijin-ga). As was customary, he was bestowed with an art name, "Kuniyoshi," combining a character from his master's name ("Kuni" from Toyokuni) and one from his given name ("Yoshi" from Yoshisaburō). His apprenticeship under Toyokuni I provided him with a solid foundation in the techniques and conventions of ukiyo-e. He learned the intricacies of designing for woodblock printing, a collaborative process involving the artist, carver, printer, and publisher.

Kuniyoshi's first published work appeared around 1814, and he continued to produce prints, primarily actor portraits and illustrations for books, during these early years. However, he struggled to achieve significant recognition, often overshadowed by his more successful Utagawa school contemporaries, particularly Utagawa Kunisada , later known as Toyokuni III, who was a fellow student under Toyokuni I and excelled in the popular genres of actor and beauty prints. These early years were reportedly marked by financial hardship for Kuniyoshi, a period that likely fueled his resilience and determination.

The Breakthrough: Warriors and Heroes

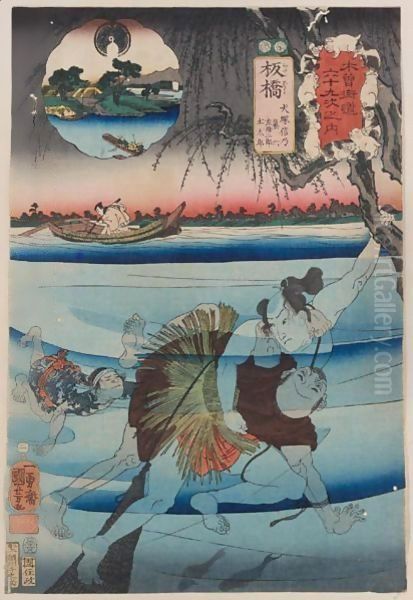

The turning point in Kuniyoshi's career arrived in the late 1820s. In 1827, he received a commission to produce a series of warrior prints (musha-e) titled One Hundred and Eight Heroes of the Popular Suikoden All Told . This series, illustrating the heroic outlaws from the popular Chinese novel Shuihu Zhuan (known as Suikoden in Japan), was an unprecedented success.

Kuniyoshi's depictions of these heroes were unlike anything seen before. He imbued his figures with extraordinary dynamism, muscular physiques often covered in elaborate tattoos, and intense, dramatic expressions. The compositions were bold and energetic, filled with action and a raw power that captivated the Edo populace. This series not only established Kuniyoshi's reputation as a master of the warrior print genre but also sparked a "Suikoden boom" in Edo, popularizing the tales and their heroic, anti-authoritarian themes. His innovative approach to musha-e set a new standard and secured his place as a leading ukiyo-e artist.

Following the success of the Suikoden series, Kuniyoshi became the preeminent designer of warrior prints. He produced numerous other series and individual prints depicting famous samurai, legendary battles, and scenes from Japanese history and mythology. Works such as Eight Hundred Heroes of the Japanese Suikoden and prints illustrating the exploits of figures like Miyamoto Musashi or the Soga brothers further solidified his fame. His warriors were not static figures but were caught in moments of intense action, their bodies contorting, weapons clashing, and emotions running high.

Navigating Censorship: The Tenpō Reforms and Satirical Wit

The Edo period, while a time of cultural flourishing, was also subject to strict governmental control by the Tokugawa shogunate. In the early 1840s, the Tenpō Reforms were enacted in response to economic crisis and perceived moral decline. These reforms imposed austerity measures and strict censorship on popular entertainment, including ukiyo-e. The depiction of actors, courtesans, and geishas—staples of the ukiyo-e market—was heavily restricted or banned.

This period of censorship posed a significant challenge to ukiyo-e artists, but Kuniyoshi, with his characteristic ingenuity and rebellious streak, found clever ways to adapt. He turned his talents towards genres that were less scrutinized, such as landscapes, nature studies (kachō-ga), and, most notably, satirical prints (giga-e). His satirical works often employed animals, particularly cats and other creatures, in anthropomorphic roles to subtly critique the government and social conditions. These prints were filled with humor, puns, and hidden meanings that would have been understood by the contemporary Edo audience.

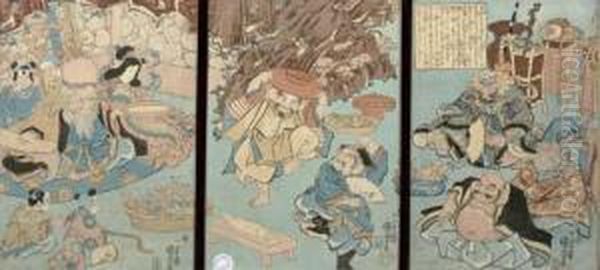

One famous example of his veiled social commentary is the triptych Minamoto no Raikō and the Earth Spider , created around 1843. Ostensibly depicting the legendary hero Minamoto no Yorimitsu (Raikō) and his retainers haunted by a giant earth spider and its demonic minions, the print was widely interpreted as an allegory for the suffering populace (the ailing Raikō) being tormented by the corrupt and ineffective shogunate (the monsters). Such works demonstrated Kuniyoshi's ability to engage with the socio-political climate of his time, using his art as a form of subtle protest. He also produced "shadow pictures" (kage-e), where assembled objects or figures cast shadows that formed different images, and "playful pictures" (omocha-e) for children, showcasing his versatility.

A Master of Diverse Genres

While renowned for his warrior prints and satirical works, Kuniyoshi's artistic repertoire was remarkably broad. He demonstrated mastery across a wide range of ukiyo-e subjects, often bringing his unique dynamism and imaginative flair to each.

Cats, Cats, and More Cats:

Kuniyoshi was a renowned ailurophile, a passionate lover of cats. His studio was said to be filled with feline companions, and they frequently appeared in his artwork. He depicted cats in realistic poses, capturing their playful antics and enigmatic grace, but also famously anthropomorphized them in humorous and satirical scenes. Series like Cats Suggested by the Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō , where cats humorously parody human activities at each station of the famous highway, are beloved examples. His cat prints showcase not only his affection for the animals but also his keen observational skills and wit.

Landscapes and Cityscapes:

Though not as prolific in landscape (fūkei-ga) as his contemporary Utagawa Hiroshige , Kuniyoshi produced notable landscape prints. He often incorporated Western-style perspective and shading techniques, which he likely studied from imported Dutch engravings. His landscapes, such as the series Famous Views of the Eastern Capital , often feature dramatic viewpoints and a sense of grandeur, sometimes with human figures engaged in lively activities, adding a narrative element to the scenery.

Mythical Creatures and Ghosts:

Kuniyoshi's vivid imagination was perfectly suited to depicting the supernatural. He created terrifying and awe-inspiring images of ghosts (yūrei), demons (oni), dragons, and other mythical beasts. His triptych Takiyasha the Witch and the Skeleton Spectre , circa 1844, is one of his most iconic works. It features a colossal skeleton looming over the protagonists, a visually stunning and technically brilliant composition that showcases his mastery of dramatic effect and his willingness to push the boundaries of ukiyo-e. These prints tapped into the popular fascination with ghost stories and the macabre in Edo society.

Beauties and Historical Scenes:

While not his primary focus, Kuniyoshi also produced prints of beautiful women (bijin-ga) and scenes from history and legend. His beauties often possessed a strength and character that distinguished them from the more demure figures favored by some other artists. His historical scenes were, like his warrior prints, filled with drama and narrative power.

Artistic Style and Innovations

Kuniyoshi's artistic style is instantly recognizable for several key characteristics:

Dynamism and Energy: His figures are rarely static; they are almost always in motion, engaged in dramatic action, or expressing intense emotion. This sense of movement and vitality is a hallmark of his work.

Bold Compositions: He favored complex and often unconventional compositions, utilizing diagonal lines, close-ups, and dramatic cropping to heighten the visual impact. His triptychs, in particular, demonstrate his skill in creating expansive and immersive scenes.

Vibrant Colors: Kuniyoshi employed a rich and often bold color palette. The introduction of Prussian blue (bero-ai) in the 1820s allowed for new expressive possibilities, which he fully exploited.

Exaggeration and Imagination: He was not afraid to exaggerate anatomical features, expressions, or the scale of elements within his compositions to enhance drama or convey character. His fantastical creatures are a testament to his unbridled imagination.

Western Influences: Kuniyoshi was open to incorporating elements of Western art, particularly in his use of perspective, shading (chiaroscuro), and anatomical rendering, which added a sense of realism and three-dimensionality to some of his works.

Narrative Power: Many of Kuniyoshi's prints tell a story, capturing a pivotal moment from a legend, historical event, or play. He had a remarkable ability to convey complex narratives and emotions through visual means.

Technical Skill: His designs were often intricate and demanding, showcasing the high level of skill achieved by the woodblock carvers and printers with whom he collaborated.

He was also an innovator in terms of format and presentation. His dramatic triptychs, often depicting large-scale battles or supernatural events, were particularly influential and allowed for a more cinematic and immersive viewing experience.

Relationships with Contemporaries and the Utagawa School

Kuniyoshi was a central figure within the Utagawa school, founded by Utagawa Toyoharu and brought to prominence by Kuniyoshi's own master, Toyokuni I. The Utagawa school dominated ukiyo-e production in the 19th century, and its artists often collaborated and competed with one another.

Kuniyoshi's most notable contemporaries within the school were Utagawa Kunisada and Utagawa Hiroshige . Kunisada was the most commercially successful ukiyo-e artist of his time, specializing in actor prints and bijin-ga. Hiroshige was, and remains, celebrated for his evocative landscape prints, particularly his series The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō. While these three artists are often considered the triumvirate of late Edo ukiyo-e, they had distinct styles and specializations. There was undoubtedly an element of rivalry, particularly between Kuniyoshi and the more commercially dominant Kunisada, but also instances of collaboration. For example, Kuniyoshi and Hiroshige collaborated on series such as The Sixty-nine Stations of the Kisokaidō (where Hiroshige did most of the designs, but Kuniyoshi contributed some) and Famous Restaurants of Edo .

Other Utagawa school artists active during or around Kuniyoshi's time included Utagawa Kunimaru , Utagawa Kuninao , and Utagawa Sadahide , who was known for his Yokohama-e (prints of foreigners in Yokohama). Kuniyoshi also interacted with artists from other schools and traditions. For instance, Katsushika Hokusai , another giant of ukiyo-e, was an older contemporary whose innovative spirit and diverse subject matter may have influenced Kuniyoshi. Keisai Eisen , known for his decadent bijin-ga, was another prominent artist of the era with whom Kuniyoshi sometimes collaborated on series.

Kuniyoshi was also an influential teacher. He nurtured a new generation of artists, many of whom adopted "Yoshi" from his name into their own. His most important pupils included:

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi : Often considered Kuniyoshi's greatest successor, Yoshitoshi further developed the dramatic and often violent themes of his master, becoming one of the last great masters of traditional ukiyo-e.

Kawanabe Kyōsai : Known as the "demon of painting," Kyōsai was a highly individualistic artist who, after studying with Kuniyoshi, developed a unique style that blended traditional Japanese painting with caricature and satire.

Utagawa Yoshiiku : A prolific artist who worked in various genres, including newspaper illustrations.

Utagawa Yoshitora : Known for warrior prints and Yokohama-e.

Utagawa Yoshikazu : Also known for warrior prints and Yokohama-e.

These students, and others like Utagawa Yoshifuji known for his toy prints (omocha-e), carried forward aspects of Kuniyoshi's dynamism and thematic interests into the Meiji period.

Key Representative Works

Kuniyoshi's oeuvre is vast and diverse, but several works stand out as particularly representative of his genius:

One Hundred and Eight Heroes of the Popular Suikoden All Told : This series was his breakthrough. Each print depicts one of the Chinese outlaw heroes in a moment of dramatic action or defiant pose. The figures are muscular, often tattooed, and exude a raw, rebellious energy. This series redefined the musha-e genre.

Takiyasha the Witch and the Skeleton Spectre : This iconic triptych depicts Princess Takiyasha, a sorceress, summoning a gigantic skeleton to menace the samurai Mitsukuni. The sheer scale and terrifying presence of the skeleton, rendered with anatomical understanding, make this one of the most memorable and impactful images in all of ukiyo-e. It showcases Kuniyoshi's mastery of the supernatural and his ability to create truly awe-inspiring compositions.

Minamoto no Raikō and the Earth Spider : Another powerful triptych, this work is famed for its allegorical critique of the Tenpō Reforms. The hero Raikō lies ill while his retainers battle a monstrous earth spider and its demonic cohorts. The scene is a whirlwind of grotesque figures and dynamic action, a visual feast that also carried a potent, albeit veiled, political message.

Nitobe Inazō (Nitobe no Shirō Tadatsune) in the Province of Higo Killing a Giant Wild Boar : This dramatic triptych shows the hero bravely confronting a monstrous boar. The sheer scale of the beast and the intensity of the confrontation are typical of Kuniyoshi's heroic scenes. (Note: The title Miyamoto Musashi and the Giant Whale is a common misattribution for a different, though equally dramatic, triptych by Kuniyoshi).

Cats Suggested by the Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō : A delightful series showcasing Kuniyoshi's love for cats and his playful wit. Each print features cats in humorous situations that punningly relate to the names of the Tōkaidō post stations.

Various series of warrior prints (musha-e): Beyond the Suikoden, Kuniyoshi produced numerous series like Biographies of Loyal and Righteous Samurai and Heroes of the Taiheiki , all characterized by their dynamism and dramatic storytelling.

These works, among many others, demonstrate the breadth of Kuniyoshi's talent, his innovative spirit, and his profound connection with the popular culture of his time.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

In his later years, Kuniyoshi continued to be a prolific and respected artist. However, his health began to decline. In 1855, he experienced the Great Ansei Earthquake, which devastated Edo, an event he and his pupil Yoshitoshi reportedly weathered together. Around this time, he may have suffered a stroke, which affected his ability to work with his former vigor, though he continued to produce designs.

Utagawa Kuniyoshi died on April 14, 1861, in Edo, at the age of 63 (by Western count). He was buried at Daisenji Temple in Asakusa. His death marked the end of an era for ukiyo-e, as Japan was on the cusp of major transformations with the impending Meiji Restoration.

Kuniyoshi's legacy is multifaceted and enduring. He was a master storyteller in visual form, whose works captured the heroism, fantasy, humor, and anxieties of his time. His innovations in composition, his dynamic portrayal of action, and his imaginative power significantly influenced the subsequent generation of ukiyo-e artists, particularly Yoshitoshi and Kyōsai, who carried the expressive potential of the medium into the Meiji period.

Beyond Japan, Kuniyoshi's work, like that of Hokusai and Hiroshige, gained appreciation in the West during the Japonisme movement of the late 19th century, influencing Impressionist and Post-Impressionist artists. In modern times, his art continues to fascinate. His dramatic warrior prints and depictions of mythical creatures have found a new audience among fans of manga, anime, and tattoo art, where his bold designs and powerful imagery resonate strongly. His cat prints remain universally charming. Major museums around the world, including the British Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, hold extensive collections of his work, ensuring its continued study and appreciation.

Conclusion

Utagawa Kuniyoshi was more than just a skilled craftsman; he was a visionary artist who pushed the boundaries of ukiyo-e. His work reflects a profound understanding of human emotion, a boundless imagination, and a rebellious spirit that often challenged convention. From the fierce loyalty of samurai warriors to the playful antics of cats, from the terrifying grandeur of mythical beasts to the subtle satire of social commentary, Kuniyoshi's art offers a vibrant and multifaceted window into the world of late Edo Japan. His ability to blend tradition with innovation, drama with humor, and realism with fantasy cements his status as one of the most important and engaging figures in the history of Japanese art. His prints continue to thrill, amuse, and inspire, a testament to the enduring power of his unique artistic vision.