Katsukawa Shunshō stands as a pivotal figure in the history of Japanese ukiyo-e, the vibrant "pictures of the floating world" that captured the zeitgeist of Edo-period Japan. Primarily celebrated for his revolutionary depictions of Kabuki actors, Shunshō injected a new level of realism and psychological depth into a genre previously characterized by stylized conventions. As the founder and leading master of the Katsukawa school, his influence extended far beyond his own prolific output, shaping the trajectory of actor portraiture and mentoring a generation of artists, including the legendary Katsushika Hokusai.

Early Life and Artistic Genesis

Born in Edo (present-day Tokyo) in 1726, Shunshō's original name was Fujiwara Masaki, later adopting Yūsuke as a common name. Details of his early life remain somewhat obscure, a commonality for many ukiyo-e artists who often hailed from artisanal or merchant-class backgrounds. It is widely accepted that he initially studied under Miyagawa Shunsui , a prominent painter of the Miyagawa school. Shunsui himself was the son and pupil of Miyagawa Chōshun , a master known for his finely detailed paintings of beauties and genre scenes, who notably refrained from producing woodblock prints.

This early training in a painting-focused school likely instilled in Shunshō a strong foundation in draftsmanship and an appreciation for nuanced depiction, qualities that would later distinguish his print designs. While the Miyagawa school specialized in nikuhitsuga (original paintings), Shunshō would eventually gravitate towards the burgeoning world of woodblock prints, a medium that allowed for wider dissemination and catered to the popular tastes of Edo's burgeoning urban populace. He also reportedly studied haikai poetry under Sōgyō, indicating a cultured background.

The Dawn of the Katsukawa School and a New Vision for Yakusha-e

By the early 1760s, Shunshō had established himself as an independent artist and began using the art-name (gō) Katsukawa Shunshō. This marked the effective founding of the Katsukawa school, which would soon become the dominant force in the field of yakusha-e (Kabuki actor prints). At this time, actor portraiture was largely dominated by the Torii school, led by artists like Torii Kiyomitsu . The Torii style, while dynamic and decorative, tended towards idealized and somewhat generic representations of actors, often making it difficult to distinguish individual performers beneath the theatrical roles they embodied. Their figures were often described with "gourd-shaped legs" and "earthworm-like lines."

Shunshō, in a bold departure, sought to capture the unique likenesses and individual personalities of the actors. His prints were not merely representations of characters on stage but portraits of the celebrated performers themselves. This innovation was revolutionary. Audiences, who were passionate fans of Kabuki stars, eagerly embraced prints that allowed them to recognize their favorite actors, complete with their distinct facial features, expressions, and even on-stage mannerisms.

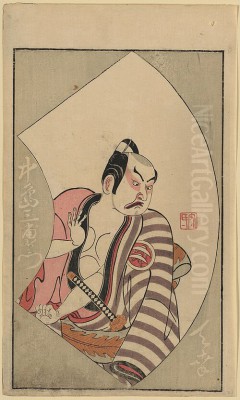

This shift towards realism coincided with the development of nishiki-e (brocade pictures), full-color woodblock prints, pioneered around 1765 by artists like Suzuki Harunobu . The availability of a richer palette allowed Shunshō and his contemporaries to create more lifelike and visually appealing images. Shunshō, along with Ippitsusai Bunchō , was at the forefront of this new wave of realistic actor portraiture. Their collaboration on the illustrated book Ehon Butai Ōgi in 1770 is considered a landmark, showcasing actors' faces with unprecedented individuality, often depicted within fan-shaped cartouches.

Artistic Style and Signature Techniques

Shunshō's style is characterized by its incisive observation and meticulous detail. He paid close attention to the actors' physiognomies, capturing the specific curve of a nose, the set of a jaw, or the intensity of a gaze. This was a significant departure from the more mask-like faces seen in earlier actor prints. His lines are typically strong yet supple, defining forms with clarity and grace.

While renowned for actor prints, Shunshō also produced bijin-ga (pictures of beautiful women). These works, though perhaps less influential than his yakusha-e, are highly regarded for their elegance and refined depiction of contemporary female beauties. His bijin-ga often exhibit a softer, more lyrical quality compared to the dramatic intensity of his actor portraits. They are considered among the finest examples of the genre from the latter half of the 18th century. One of his most notable works in this area is the series Seirō Bijin Awase Sugata Kagami , a collaborative album with Kitao Shigemasa , which depicted courtesans from the Yoshiwara district.

Shunshō was adept in various print formats. He produced numerous hoso-e (narrow vertical prints), often designed as triptychs or even pentaptychs, creating dynamic multi-sheet compositions of stage scenes. He was also a master of the ōkubi-e (large-head portrait) format, which became increasingly popular towards the end of his career, allowing for even greater focus on facial expression and individual character. His use of color was sophisticated, employing the expanding range of pigments available for nishiki-e to create rich and harmonious compositions. A distinctive feature found on some of his prints from around 1764 to 1786 is a jar-shaped seal ("tsubo"), leading to these prints sometimes being referred to as "Tsubo-e."

Beyond prints, Shunshō was also an accomplished painter, continuing the tradition of his Miyagawa school training. His nikuhitsuga often depict similar subjects to his prints – actors and beautiful women – but with the added richness and subtlety that the brush allows.

Notable Works and Thematic Focus

Shunshō's oeuvre is vast, but certain works and series stand out. His individual portraits of leading Kabuki actors of his time, such as Ichikawa Danjūrō V, Nakamura Nakazō I, and Segawa Kikunojō III, are iconic. These prints not only captured their likenesses but also conveyed the power and charisma that made them stars of the Edo stage.

For instance, his depictions of Ichikawa Danjūrō V in various roles, particularly the heroic aragoto (rough-style) characters, are celebrated for their dramatic force. He skillfully portrayed the actor's imposing presence and fierce expressions, hallmarks of the Danjūrō lineage. Similarly, his portraits of onnagata (male actors specializing in female roles), like Segawa Kikunojō III, captured the delicate grace and specific acting style of these performers.

Shunshō also produced prints depicting actors in their dressing rooms (gakuya-e), offering a behind-the-scenes glimpse into the world of Kabuki. These works satisfied the public's curiosity about the private lives of their idols and further emphasized the individuality of the actors, distinct from their stage personas. An example is "Ichikawa Danjūrō V in his Dressing Room," which shows the star in a more relaxed, informal setting.

His illustrated books, such as Yakusha Butai no Sugata-e , further cemented his reputation. These collections provided a comprehensive visual record of the Kabuki world, eagerly consumed by theater enthusiasts.

Shunshō as a Teacher: The Katsukawa School and Its Disciples

As the head of the Katsukawa school, Shunshō was a highly influential teacher, nurturing a remarkable roster of talented pupils who continued and expanded upon his artistic innovations. His studio became a powerhouse of ukiyo-e production, particularly in the realm of actor prints.

Among his most prominent students were:

Katsukawa Shunkō : Known for his powerful ōkubi-e actor portraits, Shunkō developed a distinctive style, often emphasizing dramatic expressions. Unfortunately, his career was cut short by a stroke that paralyzed his right arm, after which he turned to painting with his left hand.

Katsukawa Shun'ei : Shun'ei became a leading figure in actor portraiture after Shunshō's death. He continued his master's realistic approach but often imbued his figures with a greater sense of monumentality and sometimes a more forceful, even stark, quality. He is also known for his sumo wrestler prints.

Katsukawa Shunchō : While trained in the Katsukawa tradition of actor prints, Shunchō is particularly celebrated for his elegant bijin-ga, which show the influence of Torii Kiyonaga in their depiction of tall, graceful figures.

Katsukawa Shunzan : Another artist who produced both actor prints and bijin-ga, often reflecting the prevailing styles of his time.

Perhaps the most famous artist to emerge from Shunshō's studio was Katsushika Hokusai . Hokusai, then known as Tokitarō, joined Shunshō's school around the age of 18 or 19, in 1778 or 1779. He was given the art-name Katsukawa Shunrō , incorporating the "Shun" from his master's name, a common practice signifying artistic lineage and Shunshō's approval.

Under Shunshō, Hokusai primarily designed actor prints in the Katsukawa style. He learned the fundamentals of realistic portrayal and the intricacies of the ukiyo-e production process. Sources suggest he studied under Shunshō for a period variously cited as three to fourteen years. However, Hokusai's restless artistic curiosity eventually led him to explore other styles, including those of the Kanō school and Western-influenced art.

His departure from the Katsukawa school, around 1794 (shortly after Shunshō's death in early 1793, or perhaps even before, during Shunshō's final years), is a subject of some discussion. One account suggests a falling out with Shunshō's chief successor, possibly Shunkō, who may have disapproved of Hokusai's exploration of other artistic avenues. Another version mentions an incident where a senior student, possibly Shunkō or Katsukawa Haruyoshi, criticized or even destroyed a signboard Hokusai had painted for a print seller, leading to Hokusai's decision to leave. Regardless of the precise reasons, Hokusai embarked on an independent path, eventually becoming one of the most versatile and innovative artists in Japanese history, renowned for works like "The Great Wave off Kanagawa" and "Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji." Despite his later divergence, the foundational training Hokusai received from Shunshō in realistic depiction and composition was undoubtedly formative.

Interactions with Contemporaries and the Broader Art World

Shunshō operated within a dynamic and competitive art world. His innovations in actor portraiture directly challenged the established Torii school. While he collaborated successfully with Ippitsusai Bunchō, who shared his vision for realistic yakusha-e, he also worked alongside artists from other schools. His collaboration with Kitao Shigemasa on Seirō Bijin Awase Sugata Kagami demonstrates a willingness to engage with artists known for different specializations; Shigemasa was a prominent figure in his own right, leading the Kitao school and excelling in bijin-ga and illustrated books.

The rise of the Katsukawa school under Shunshō effectively eclipsed the Torii school in actor portraiture for a period. However, the Torii school, particularly under Torii Kiyonaga, later experienced a resurgence, especially in the realm of bijin-ga and more generalized, elegant depictions of actors in full-length scenes. Kiyonaga's style, with its tall, graceful figures, became immensely popular in the 1780s and influenced many artists, including some from the Katsukawa lineage like Shunchō.

Shunshō's work also needs to be seen in the context of other leading ukiyo-e masters of his era. Suzuki Harunobu had revolutionized printmaking with nishiki-e just as Shunshō was hitting his stride. Isoda Koryūsai , another contemporary, was known for his pillar prints (hashira-e) and extensive series of bijin-ga. Later in Shunshō's career, artists like Kitagawa Utamaro would take bijin-ga, particularly ōkubi-e of beauties, to new heights of psychological expressiveness, building upon the foundations of realism and detailed observation that Shunshō had championed in actor prints.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Katsukawa Shunshō continued to be a prolific and respected artist until his death in Edo in early 1793 (the second day of the twelfth month of Kansei 4, which corresponds to January 13, 1793, in the Gregorian calendar). In his later years, he increasingly focused on painting, perhaps returning to the roots of his initial training. His death marked the end of an era, but the Katsukawa school, through his talented disciples like Shun'ei and Shunkō, continued to dominate actor portraiture for some time.

The influence of Shunshō's realism extended to the next generation of ukiyo-e artists, including those of the burgeoning Utagawa school, founded by Utagawa Toyoharu . Artists like Utagawa Toyokuni I further developed realistic actor portraiture, often with a heightened sense of drama and dynamism, building on the Katsukawa legacy. Subsequently, Toyokuni's students, such as Utagawa Kunisada and Utagawa Kuniyoshi , would become dominant forces in 19th-century ukiyo-e, with their actor prints clearly showing an inheritance from the Katsukawa school's innovations. Even Utagawa Hiroshige , though famed for landscapes, produced actor prints early in his career that reflected this tradition.

Art Historical Significance and Evaluation

Katsukawa Shunshō's position in Japanese art history is secure and significant. He is universally recognized as the artist who transformed yakusha-e from a genre of stylized representations into one of true portraiture. By emphasizing the individual likenesses of actors, he catered to the sophisticated demands of Edo's theater-going public and elevated the artistic status of actor prints.

His founding of the Katsukawa school created an institution that not only dominated its field for decades but also served as a crucial training ground for numerous artists, including the exceptionally gifted Hokusai. While Hokusai's later fame and international recognition may have overshadowed Shunshō's in popular perception, art historians acknowledge Shunshō's foundational role. Indeed, without the Katsukawa school's emphasis on realistic depiction, the trajectory of Hokusai's early development, and by extension, aspects of his later work, might have been different.

Shunshō's works are praised for their technical skill, psychological insight, and historical importance as documents of Kabuki culture during its golden age. They offer an invaluable window into the vibrant world of Edo-period theater, capturing not just the spectacle but also the personalities who brought it to life. His prints are considered among the finest artistic achievements of the 18th century in Japan. While perhaps not as widely known internationally as Hokusai, Utamaro, or Hiroshige, Katsukawa Shunshō remains a towering figure for connoisseurs of ukiyo-e and a crucial innovator in the history of Japanese art. His dedication to realism and his ability to capture the essence of his subjects set a new standard, profoundly influencing the artists who followed and forever changing the landscape of ukiyo-e.