Torii Kiyonaga (1752–1815) stands as one of the most influential and celebrated artists of Japan's Edo period, a pivotal figure in the world of ukiyo-e, or "pictures of the floating world." His refined aesthetic, particularly in the depiction of graceful female figures and dynamic group compositions, left an indelible mark on the art form. Born Sekiguchi Shinsuke in Edo (present-day Tokyo), he rose to prominence not through blood relation to the esteemed Torii school of artists but through sheer talent and dedication, eventually becoming its fourth head. His productive years, especially the 1780s, are often considered a golden age for bijinga (pictures of beautiful women), and his work set a standard that many contemporaries and successors aspired to or reacted against.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

The precise details of Kiyonaga's earliest years are somewhat sparse, a common trait for many ukiyo-e artists who often came from artisanal or merchant-class backgrounds. He was born in 1752 in Uraga, a port town near Edo, to a family of booksellers named Shirokoya Ichibei. His given name was Seki Shinsuke, later adopting the name Ichibei. This connection to the publishing world may have provided him with early exposure to printed materials and illustrations, potentially sparking his interest in art.

At a young age, likely around fourteen, he moved to Edo and became a pupil of Torii Kiyomitsu (1735–1785), the third head of the Torii school. The Torii school was, at that time, the dominant force in producing actor prints (yakusha-e) and theatrical signboards (kanban) for the Kabuki theaters. Under Kiyomitsu's tutelage, Kiyonaga would have learned the foundational techniques of woodblock print design, the specific stylistic conventions of the Torii school, and the demands of the Kabuki world. He adopted the art name Kiyonaga, with the "Kiyo" prefix being characteristic of the Torii lineage.

Rise to Prominence and the Torii School

Kiyonaga's early works, appearing around 1767, were primarily in the established Torii style, focusing on Kabuki actors. These initial prints, while competent, showed the influence of his master, Kiyomitsu, and other prominent actor-print artists of the time like Katsukawa Shunshō (1726–1792), who was revolutionizing actor portraiture with greater realism. However, Kiyonaga soon began to distinguish himself.

Upon the death of Torii Kiyomitsu in 1785, Kiyonaga, despite not being a blood relative, was chosen to become the fourth head of the Torii school. This was a testament to his artistic skill and his standing within the ukiyo-e community. While he continued to produce actor prints, fulfilling the traditional role of the Torii school, his true passion and innovation lay elsewhere, particularly in the realm of bijinga. His leadership of the school coincided with his peak period of creativity in depicting beautiful women.

The Apogee of Bijinga: Kiyonaga's Signature Style

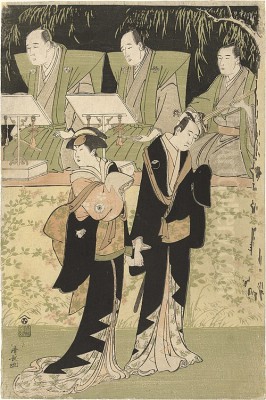

The Tenmei era (1781–1789) is often referred to as the "Kiyonaga period" in the history of bijinga, highlighting his dominance and stylistic influence. Kiyonaga revolutionized the depiction of female figures. He moved away from the delicate, almost ethereal beauties popularized by Suzuki Harunobu (c. 1725–1770) in the 1760s. Kiyonaga's women were taller, more statuesque, and imbued with a sense of robust, healthy elegance. They possessed a natural grace, often depicted with elongated proportions that conveyed a sophisticated poise.

His figures were not isolated icons but were frequently shown in groups, interacting with each other and their environment. This is one of Kiyonaga's most significant contributions: the mastery of multi-sheet compositions, particularly diptychs and triptychs. He skillfully arranged figures across two or three separate sheets of paper, creating panoramic scenes that flowed seamlessly. These compositions often depicted women on outings, such as boating trips on the Sumida River, visiting temples, or strolling through scenic locales like Shinagawa.

Kiyonaga's backgrounds were also more developed and integrated than those of many of his predecessors. He often included detailed architectural elements or recognizable landscapes, grounding his figures in a tangible reality. This contrasted with the more abstract or suggestive backgrounds common in earlier bijinga. His use of color was refined and harmonious, employing the full capabilities of nishiki-e (brocade prints, or full-color prints) to create subtle and appealing palettes.

Representative Works and Series

Kiyonaga's oeuvre is rich with masterpieces that exemplify his unique style. Among his most celebrated series and individual prints are:

"Minami Jūnikō" (Twelve Hours in the Minami [Shinagawa District], c. 1780s): This series depicted courtesans and geishas of the Shinagawa pleasure district at different times of the day, showcasing their activities and elegant attire. These prints are notable for their sophisticated compositions and the graceful portrayal of the women.

"Tōsei Yuri Bijin Awase" (A Contest of Contemporary Beauties of the Gay Quarters, c. 1784): This series presented paired beauties from different pleasure quarters, often highlighting their distinctive styles and charms. It demonstrated Kiyonaga's ability to capture subtle nuances in fashion and demeanor.

"Fūzoku Azuma no Nishiki" (Customs and Manners of the Eastern Capital in Brocade Pictures, c. 1783-1785): A series showcasing various scenes of daily life and leisure in Edo, featuring his characteristic elegant figures in beautifully rendered settings.

Beyond these series, Kiyonaga produced numerous standalone diptychs and triptychs that are considered high points of ukiyo-e. Examples include scenes of women disembarking from a boat, groups enjoying the cool evening breeze, or participating in seasonal festivals. His ability to manage complex group compositions, where each figure retains individuality while contributing to a harmonious whole, was unparalleled in his time.

He also produced shunga (erotic art), as did most ukiyo-e artists. These works, while explicit, often displayed the same artistic skill and elegance found in his mainstream prints, featuring beautifully rendered figures and intricate details.

Kiyonaga and His Contemporaries

The late 18th century was a vibrant period for ukiyo-e, and Kiyonaga worked alongside and influenced many talented artists.

His teacher, Torii Kiyomitsu, provided his foundational training in the Torii school style, which specialized in actor prints and theatrical signboards. Kiyonaga, while respecting this tradition, significantly expanded the school's repertoire with his focus on bijinga.

Suzuki Harunobu was a key predecessor whose delicate and poetic bijinga defined the 1760s. Kiyonaga's taller, more robust, and naturalistic figures marked a clear departure from Harunobu's style, setting a new trend.

Isoda Koryūsai (1735–c. 1790) was a contemporary who also excelled in bijinga, particularly in the hashira-e (pillar print) format. There are stylistic similarities in their elongated figures, and Koryūsai's work likely influenced Kiyonaga's development.

Kitao Shigemasa (1739–1820) was another influential contemporary known for his realistic bijinga and illustrated books. Shigemasa's move towards greater naturalism in depicting women was a trend that Kiyonaga embraced and perfected.

Katsukawa Shunshō (1726–1792) was the leading figure in actor prints during Kiyonaga's rise. While Kiyonaga also produced actor prints, Shunshō's focus on capturing the individual likeness and dramatic intensity of Kabuki performers set a high standard in that genre. Kiyonaga's actor prints, though skilled, are generally overshadowed by his bijinga. Other artists from the Katsukawa school, such as Katsukawa Shunchō and Katsukawa Shun'ei, were also active during this period, contributing to the richness of Kabuki imagery.

Kitagawa Utamaro (c. 1753–1806) is perhaps the artist most often compared with Kiyonaga, as he became the next dominant figure in bijinga from the 1790s onwards. Utamaro's style differed significantly; he often focused on half-length portraits (ōkubi-e) that explored the psychological nuances of his subjects, particularly courtesans of the Yoshiwara district. While Kiyonaga's women were elegant and graceful in social settings, Utamaro's were often more sensual and introspective. Utamaro's rise coincided with a decline in Kiyonaga's print output.

Chōbunsai Eishi (1756–1829) was another prominent bijinga artist who emerged in the late 1780s and 1790s. Eishi, himself of samurai background, depicted tall, slender, and exceedingly refined women, often in courtly or idealized settings. His style can be seen as an extension of Kiyonaga's elegance, but with a more aristocratic and sometimes less earthy feel.

Kubo Shunman (1757–1820) was a multi-talented artist known for his refined bijinga, surimono (privately commissioned prints), and literary pursuits. His work often featured delicate color palettes and a gentle, poetic sensibility, sharing some common ground with Kiyonaga's sophisticated aesthetic.

Tōshūsai Sharaku (active 1794–1795), though his career was brief and focused almost exclusively on actor prints, produced some of the most powerful and psychologically penetrating portraits in ukiyo-e history. His dramatic and often unflattering depictions of actors were a stark contrast to the more conventional styles of the Torii or Katsukawa schools.

The founder of the Utagawa school, Utagawa Toyoharu (1735–1814), was also a contemporary, known for his pioneering work in uki-e (perspective prints) that incorporated Western-style perspective. His student, Utagawa Toyokuni I (1769–1825), would later become a dominant force in actor prints, carrying the Utagawa school to great prominence in the 19th century.

Even the great Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849) began his artistic career during Kiyonaga's peak, initially working in the style of Katsukawa Shunshō before developing his own unique and immensely varied artistic path.

This vibrant artistic milieu provided a backdrop of competition, influence, and innovation. Kiyonaga's distinct style carved out a significant niche, and his influence was palpable on many of these artists, particularly those specializing in bijinga.

Later Years, Artistic Shift, and Legacy

By the early 1790s, Kiyonaga's production of single-sheet prints began to decline. This shift coincided with the rise of new talents like Utamaro and Eishi, who were capturing the public's imagination with their distinct approaches to bijinga. There are several theories for Kiyonaga's reduced output in printmaking. Some scholars suggest that he increasingly turned his attention to painting (nikuhitsuga) and book illustration.

As head of the Torii school, he also had responsibilities in training pupils and overseeing the production of theatrical signboards, a traditional and important function of the school. The provided information suggests he focused on school work and training his successor. His primary pupil and adopted son, Torii Kiyomine (1787–1868), eventually succeeded him as the fifth head of the Torii school, continuing its traditions into the 19th century.

The anecdote mentioned in the initial information about Kiyonaga "persuading his son not to become an artist to avoid disputes" is intriguing. If this refers to a biological son rather than his adopted successor Kiyomine, it might reflect concerns about the precariousness of an artist's life or internal family dynamics. However, standard art historical accounts emphasize his role in mentoring Kiyomine to ensure the continuity of the Torii school. It's possible this refers to a desire to avoid conflict over the Torii school headship, ensuring a smooth transition to Kiyomine.

Torii Kiyonaga passed away on June 28, 1815, at the age of 63. He left behind a legacy of profound elegance and innovation in ukiyo-e. His vision of idealized yet relatable female beauty, presented in harmonious group compositions and integrated with their surroundings, defined an era. His work represents a peak of classical grace in ukiyo-e, a standard of refined beauty that influenced subsequent generations of artists.

Historical Evaluation and Enduring Influence

Torii Kiyonaga is consistently ranked among the top masters of ukiyo-e. His impact on the genre of bijinga was transformative. He established a new ideal of female beauty—tall, slender, and graceful figures that exuded an air of sophistication and health. This "Kiyonaga beauty" became the dominant style for nearly a decade and served as a benchmark for subsequent artists.

His mastery of the diptych and triptych formats, creating expansive and harmonious panoramic scenes, was a significant technical and artistic achievement. He demonstrated how multiple sheets could be unified into a cohesive and dynamic composition, a technique that later artists like Utamaro and Hokusai would also employ to great effect.

While later artists like Utamaro explored more intimate psychological portrayals, and Hokusai and Hiroshige expanded the landscape genre, Kiyonaga's contribution lies in his perfection of a certain classical elegance. His prints are admired for their balanced compositions, refined color sense, and the sheer beauty of his figures.

Kiyonaga's influence extended beyond Japan. Like other ukiyo-e masters, his works were among those that reached Europe and America in the late 19th century, contributing to the Japonisme movement that captivated Western artists. Impressionist and Post-Impressionist painters such as Edgar Degas, Mary Cassatt, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec were inspired by the compositional techniques, flattened perspectives, and everyday subject matter of ukiyo-e prints, including those from Kiyonaga's era. While Kiyonaga himself might not be as singularly famous in the West as Hokusai or Hiroshige, his artistic period represents a crucial phase of ukiyo-e's development that was part of this broader cultural exchange.

Conclusion: An Architect of Grace

Torii Kiyonaga's career represents a high point in the history of Japanese woodblock prints. As the fourth head of the Torii school, he honored its traditions while simultaneously forging a new path, particularly in the realm of bijinga. His depiction of tall, elegant women, often arranged in sophisticated group compositions against beautifully rendered backgrounds, set a new standard for grace and refinement in ukiyo-e. His works from the Tenmei era (1781-1789) are particularly celebrated, embodying a classical poise that continues to captivate art lovers and collectors worldwide. Though his print output waned in his later years as he focused on painting and his duties to the Torii school, his legacy as a master of elegance and a pivotal figure in the "floating world" remains undiminished. His art provides a timeless window into the sophisticated urban culture of Edo and the enduring appeal of beauty captured with consummate skill.