Francis Gruber stands as a poignant figure in 20th-century French art, a painter whose intense, often unsettling realism offered a powerful counterpoint to the prevailing currents of abstraction. Active primarily during the turbulent 1930s and 1940s, his career was tragically cut short by illness, yet his work left an indelible mark, prefiguring the post-war movement known as Miserabilism. His paintings, characterized by their stark honesty, elongated figures, and somber palettes, delve into the anxieties and frailties of the human condition, reflecting both personal struggles and the broader historical context of his time.

Born in Nancy, France, in 1912, Gruber's artistic path was set early, yet it diverged significantly from traditional academic routes. His father, Jacques Gruber, was a noted American master stained-glass artist associated with the École de Nancy, immersing the young Francis in an environment where art and craft were paramount. However, chronic asthma plagued Gruber from childhood, often confining him indoors and limiting his formal education. This physical vulnerability would profoundly shape his worldview and artistic output.

Despite his health challenges, Gruber displayed a precocious talent and a voracious appetite for art history. Largely self-taught, he spent countless hours studying and copying the masters, not in the academies, but through reproductions and museum visits when his health permitted. He briefly attended the Académie Scandinave in Montparnasse around 1929-1930, a liberal environment frequented by artists like Alberto Giacometti, whom he would later befriend. However, his most profound tutelage came from his deep engagement with historical art.

Echoes of the Masters: Formative Influences

Gruber developed a particular fascination with the Northern Renaissance masters, especially those from Germany and the Low Countries. The meticulous detail, psychological intensity, and often unsettling visions of artists like Albrecht Dürer, Matthias Grünewald, Hieronymus Bosch, and Lucas Cranach the Elder resonated deeply with him. He admired their unflinching portrayal of suffering, their complex allegories, and their mastery of line. The expressive linearity and sometimes grotesque realism found in Grünewald's Isenheim Altarpiece, for instance, find echoes in Gruber's own attenuated figures and stark settings.

Another crucial influence was the 17th-century Lorraine artist Jacques Callot. Callot's etchings, particularly his series "Les Grandes Misères de la guerre" (The Miseries and Misfortunes of War), provided a model for depicting human suffering and the harsh realities of conflict with graphic honesty. Gruber paid direct tribute to him in works like Hommage à Jacques Callot (Homage to Jacques Callot), created in several versions, notably one during the dark years of the German Occupation of Paris. This choice of influence signaled Gruber's commitment to an art grounded in observable reality and human drama, rather than purely formal experimentation.

These historical anchors provided Gruber with a rich visual and thematic vocabulary, distinct from the Cubist and Surrealist movements that had dominated the Parisian avant-garde in the preceding decades. While aware of contemporaries like Pablo Picasso and the Surrealists led by André Breton, Gruber consciously forged a path rooted in figurative representation, albeit one infused with modern anxieties.

Forging a Style: Realism and Anxiety

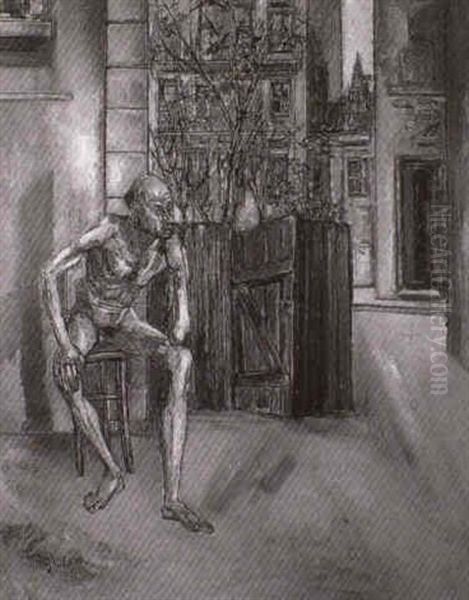

By the early 1930s, Gruber began exhibiting his work and developing his signature style. His paintings often feature gaunt, elongated figures set within sparse, claustrophobic interiors. His nudes, portraits, and studio scenes are rendered with a sharp, incisive line and a palette dominated by earthy tones, ochres, grays, and melancholic blues and reds. There is a palpable sense of unease, solitude, and physical vulnerability in his subjects. The figures often seem weighed down by an invisible burden, their large, expressive eyes conveying deep introspection or quiet despair.

His approach aligned him briefly with the "Forces Nouvelles" (New Forces) group, founded around 1935 by artists like Robert Humblot and the critic Henri Héraut. This group advocated for a return to realism and traditional craftsmanship, reacting against what they perceived as the excesses of abstraction and Surrealism. They sought an art connected to human experience and observable reality. While Gruber shared their commitment to figuration and drawing, his work possessed a psychological depth and expressive intensity that set him apart.

Gruber's realism was not merely descriptive; it was deeply subjective and expressive. He used distortion, particularly the elongation of limbs and torsos, not for formal experimentation in the manner of Amedeo Modigliani, but to heighten the emotional and psychological impact. His figures often appear fragile, almost skeletal, emphasizing their precarious existence. This distinctive style became increasingly pronounced throughout the 1930s and into the war years.

The Studio and the Self

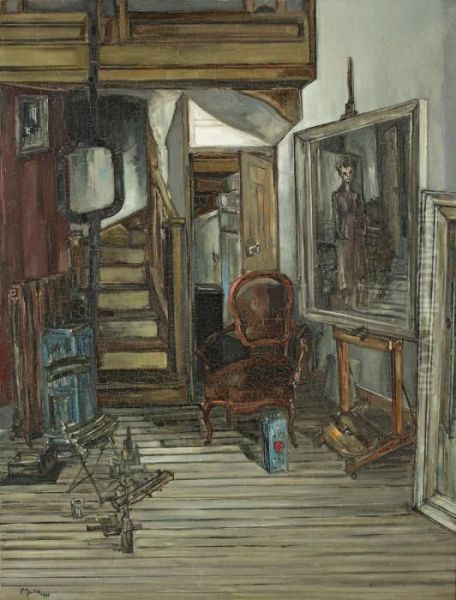

The artist's studio became a recurring and significant motif in Gruber's work. These paintings, such as the various versions of L'Atelier (The Studio), are more than just depictions of his working space; they are intimate self-portraits and reflections on the act of creation itself. Often sparsely furnished, cluttered with canvases and the tools of his trade, the studio appears as both a sanctuary and a site of struggle. The artist, sometimes represented directly, sometimes implicitly through the objects depicted, confronts the canvas and the challenges of representation.

These studio scenes often include nude models, rendered with the same unflinching honesty and vulnerability as his other figures. Works like Nu au lit rouge (Nude on a Red Bed, 1944) or Femme sur un divan (Woman on a Divan) depict the female form without idealization. The flesh might appear pale, the poses awkward, the settings stark. Gruber explores the physical presence of the body, its weight, its textures, and its inherent fragility, often imbued with a sense of melancholy or resignation.

His self-portraits, though less numerous, are equally revealing. They convey a sense of intense self-scrutiny, reflecting his physical ailments and the psychological pressures of his time. He presents himself without vanity, his features often drawn and marked by suffering, yet imbued with a determined gaze. These works underscore the personal dimension of his art, where the external world and the internal landscape are inextricably linked.

Friendship and Dialogue: Alberto Giacometti

A crucial relationship in Gruber's life and artistic development was his close friendship with the Swiss-Italian sculptor and painter Alberto Giacometti. They likely met in the late 1920s or early 1930s in Montparnasse. Despite their different artistic trajectories – Giacometti's path led him through Surrealism before arriving at his iconic attenuated figures – they shared a profound existential questioning and an obsessive engagement with representing the human form and its place in space.

Both artists grappled with the difficulty of capturing reality, the elusiveness of presence, and the isolation of the individual. They shared a commitment to drawing and a relentless scrutiny of their subjects. Their conversations and mutual respect undoubtedly fueled their respective explorations. Gruber painted a remarkable portrait of Giacometti around 1946, capturing his friend's intense gaze and gaunt features with characteristic acuity. This portrait stands as a testament to their deep connection and shared artistic concerns.

While Giacometti's figures became increasingly dematerialized, striving to capture perception itself, Gruber remained focused on the tangible, albeit emotionally charged, reality of the body and its environment. Yet, both artists, in their distinct ways, conveyed the anxieties and existential dilemmas of the modern era through the human form. Their friendship highlights a significant current in mid-century Parisian art that resisted pure abstraction, seeking meaning in the figurative representation of human experience.

The War Years: Witness to Hardship

The German Occupation of Paris (1940-1944) was a period of immense hardship and moral complexity, and it profoundly impacted Gruber's work. Confined to his studio for long periods due to both the political situation and his worsening health (tuberculosis was diagnosed), his art took on an even greater intensity and somberness. His paintings from this era often reflect the scarcity, fear, and psychological weight of life under Occupation.

His 1944 painting Job is perhaps his most famous work from this period and arguably one of his masterpieces. Depicting the biblical figure synonymous with inexplicable suffering, Gruber's Job is a gaunt, near-naked figure seated resignedly amidst a desolate landscape hinted at through the studio window. The painting became an emblem of endurance and suffering, resonating deeply with the experiences of Parisians during the war. It powerfully conveys a sense of resilience in the face of overwhelming adversity, a theme central to Gruber's art.

During the Occupation, continuing to paint recognizable, often suffering, human figures was itself a form of resistance against the dehumanizing forces at play. While artists like Jean Fautrier developed thick impasto techniques in his Otages (Hostages) series to represent the victims of violence, and Jean Dubuffet began exploring Art Brut, Gruber maintained his sharp, linear realism to bear witness to the psychological toll of the era. His commitment to figuration provided a necessary anchor in a world seemingly falling apart.

Precursor to Miserabilism

Francis Gruber died of tuberculosis in Paris in December 1948, at the young age of 36. His death cut short a career that was gaining increasing recognition. Although he did not live to see the full flourishing of the post-war art scene, his work is widely considered a crucial precursor to the movement known as Miserabilism, which gained prominence in the late 1940s and 1950s.

Miserabilism, most famously associated with the young painter Bernard Buffet, depicted the angst, poverty, and disillusionment of the post-war era. Buffet's style, characterized by elongated figures, stark black outlines, and bleak subject matter, clearly owes a significant debt to Gruber. Gruber's focus on suffering, his linear precision, his somber palette, and his existential themes laid the groundwork for this later movement. Artists like Buffet and Jean Carzou continued this exploration of human hardship, though sometimes with a more stylized or mannered approach than Gruber's raw intensity.

Gruber's legacy lies in his unwavering commitment to a form of realism infused with deep psychological and emotional content. In an era where abstraction, championed by artists like Serge Poliakoff and Nicolas de Staël (in his later phase), was gaining ascendancy, Gruber, along with figures like Balthus (though with a very different sensibility) and Chaïm Soutine (an earlier expressionist influence), insisted on the power of the human figure to convey profound truths about the modern condition.

Posthumous Recognition and Legacy

Following his death, Gruber's work received further attention. A retrospective exhibition was held at the Musée National d'Art Moderne in Paris in 1950, solidifying his reputation. His paintings entered major museum collections in France and abroad. While perhaps not as widely known internationally as some of his contemporaries who embraced abstraction or Surrealism, Gruber holds a significant place in the narrative of 20th-century French figurative painting.

His influence extended beyond the direct lineage of Miserabilism. His dedication to drawing and his intense observation of reality resonated with later generations of figurative painters. His work serves as a reminder that realism, far from being a monolithic or outdated style, can be a potent vehicle for expressing complex emotions and commenting on the human condition, especially during times of crisis. He demonstrated that figurative art could be intensely modern and relevant, challenging the notion that abstraction held a monopoly on avant-garde expression.

Compared to the often enigmatic or dreamlike scenes of Balthus, or the visceral, painterly expressionism of Chaïm Soutine or Georges Rouault, Gruber's art possesses a unique clarity and starkness. His line is precise, his compositions often starkly simple, focusing attention directly on the psychological state of his subjects. He stripped away embellishment to get to the core of human vulnerability.

Conclusion: An Art of Intense Honesty

Francis Gruber's artistic journey was a testament to resilience in the face of physical suffering and historical turmoil. His relatively small oeuvre, produced over less than two decades, is characterized by its remarkable consistency of vision and its profound emotional depth. He chose the path of realism in an age leaning towards abstraction, but his was not a nostalgic or academic realism. It was a modern realism, sharpened by existential anxiety and informed by a deep understanding of art history, particularly the unflinching honesty of Northern European masters and the graphic power of Callot.

His gaunt figures, stark interiors, and somber palettes capture a sense of precariousness and solitude that speaks powerfully of his time, yet transcends it. As a friend and contemporary of Giacometti, and a clear precursor to Buffet and the Miserabilist movement, Gruber occupies a crucial, if sometimes overlooked, position in the complex landscape of mid-20th-century art. His legacy is one of intense honesty, technical skill deployed in the service of emotional truth, and an unwavering focus on the enduring, fragile, yet resilient human spirit. His work continues to resonate with its stark portrayal of the human condition, rendered with both precision and profound empathy.