László Moholy-Nagy stands as a towering figure in the landscape of 20th-century modernism. A Hungarian-born artist, theorist, photographer, designer, and educator, his relentless experimentation and visionary approach bridged the perceived gap between art and technology, leaving an indelible mark on multiple creative fields. Associated prominently with the influential Bauhaus school and later founding its successor in Chicago, Moholy-Nagy was a true polymath whose work continues to resonate with contemporary aesthetics and design thinking. His life and career trace a path through the turbulent heart of European modernism and its transplantation to America, embodying a spirit of ceaseless inquiry and a profound belief in the transformative power of a "new vision."

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born László Weisz on July 20, 1895, in Bácsborsód, a village in Southern Hungary (now part of Romania), the artist later adopted the surname Moholy-Nagy. This change reflected both his upbringing near the town of Mohol and gratitude towards a supportive uncle named Nagy. His early education took place at the state gymnasium in Szeged, a rigorous institution where he studied a wide range of classical subjects but showed particular interest in literature and art history. Initially aspiring to be a writer, his path took a detour towards law studies in Budapest.

The outbreak of World War I dramatically altered his course. Moholy-Nagy enlisted in the Austro-Hungarian army and served on the front lines. It was during a period of convalescence after being wounded that he began to draw and paint seriously, channeling his experiences and observations into visual form. This wartime initiation into art marked a definitive shift in his ambitions. After the war, he briefly returned to Budapest but soon became involved with the city's burgeoning avant-garde circles, connecting with figures like the activist artist and writer Lajos Kassák.

Influenced by the radical energy of Dadaism and the structural clarity of Russian Constructivism, Moholy-Nagy's early work began to take shape. He moved through Vienna before settling in Berlin in 1920, a vibrant hub of artistic innovation. There, he immersed himself in the experimental milieu, developing his abstract style and beginning his lifelong exploration of light, transparency, and industrial materials. It was also in Berlin that he met and married Lucia Schulz, who became an important photographer and collaborator in her own right.

The Bauhaus Years: Forging a New Vision

In 1923, a pivotal opportunity arose when Walter Gropius, founder of the Bauhaus, invited Moholy-Nagy to join the faculty of the influential art and design school, then located in Weimar. This appointment marked the beginning of a highly productive and influential period. Moholy-Nagy succeeded Johannes Itten in teaching the crucial Vorkurs (preliminary course) and later took charge of the Metal Workshop when the school moved to Dessau. His presence injected a fresh wave of experimental energy, strongly advocating for the integration of art, technology, and industry.

At the Bauhaus, Moholy-Nagy championed what he termed the "New Vision" (Neues Sehen), a concept rooted in the belief that photography, film, and new technologies could extend human perception and reveal the world in unfamiliar ways. He encouraged students to experiment with materials, explore the properties of light and space, and abandon traditional artistic hierarchies. His teaching philosophy emphasized process, experimentation, and the social responsibility of the artist and designer. He believed art should not be confined to galleries but should actively shape the modern environment.

He worked closely with Gropius and other key Bauhaus figures like the painter and stage designer Oskar Schlemmer, contributing significantly to the school's publications and theoretical discourse. His own influential books from this period, Painting, Photography, Film (1925) and The New Vision: From Material to Architecture (1928), articulated his core ideas and became essential texts for understanding modernist principles. He collaborated extensively with his first wife, Lucia Moholy, particularly in documenting Bauhaus activities and experimenting with photographic techniques. His colleagues included luminaries such as Josef Albers and Herbert Bayer, contributing to the uniquely collaborative and innovative atmosphere of the school.

Experiments in Light and Motion

Central to Moholy-Nagy's artistic practice and theoretical framework was his fascination with light. He saw light not merely as a means of illumination but as a creative medium in itself, capable of shaping space, defining form, and conveying motion. This interest manifested most dramatically in his photographic experiments and his kinetic sculptures. He became a key proponent of the photogram – a cameraless photographic technique where objects are placed directly onto light-sensitive paper and exposed, creating ethereal silhouettes and abstract compositions. He referred to his own photograms as "light prints," emphasizing the medium's essence.

These experiments pushed the boundaries of traditional photography, moving beyond representation towards pure abstraction and the manipulation of light and shadow. His photograms explored transparency, overlapping forms, and the interplay of textures, revealing the hidden aesthetic potential within everyday objects and materials. This work was intrinsically linked to his concept of the "New Vision," demonstrating how unconventional techniques could foster new ways of seeing.

Perhaps his most famous creation embodying these principles is the Light Prop for an Electric Stage (1930), also widely known as the Light Space Modulator. This kinetic sculpture, constructed from polished metal and translucent plastic parts, was designed to rotate and project complex patterns of light and shadow onto surrounding surfaces. It was conceived as a device for demonstrating and exploring spatio-temporal light effects, essentially painting with light in motion. Accompanied by his experimental abstract film Ein Lichtspiel: schwarz weiss grau (A Lightplay: Black White Gray), the Light Space Modulator became a landmark achievement in kinetic art and a testament to Moholy-Nagy's pioneering integration of art, technology, and performance. His explorations in Berlin sometimes involved exchanges with other artists interested in kinetics and construction, such as Naum Gabo.

Photography and the 'New Vision'

Moholy-Nagy's contribution to photography extends far beyond the photogram. He was a fervent advocate for the camera as a tool uniquely suited to modern life, capable of capturing the dynamism, fragmentation, and altered perspectives of the 20th century. His concept of the "New Vision" (Neues Sehen) profoundly impacted photographic practice and theory. He urged photographers to break free from the conventions of pictorialism and painting, embracing the camera's inherent capabilities.

This involved experimenting with unconventional viewpoints, such as extreme high angles (bird's-eye view) and low angles (worm's-eye view), which defamiliarized ordinary scenes and emphasized abstract patterns and geometric structures. He also championed techniques like close-ups, sharp focus, and the juxtaposition of textures. His own photographs often feature dramatic diagonals, strong contrasts between light and shadow, and reflections, capturing the energy of the modern city or revealing unexpected beauty in industrial forms. Works like Lago Maggiore, Ascona, Switzerland (1930) exemplify his ability to find abstract compositions within the real world.

Furthermore, Moholy-Nagy was a pioneer of photomontage, which he termed "photoplastics." Unlike the politically charged montages of the Berlin Dadaists, his photoplastics were often more poetic and surreal, combining photographic fragments with drawn elements to create complex visual narratives or explore psychological states. He saw photomontage as a way to condense information, create simultaneous viewpoints, and express the multifaceted nature of modern experience. His advocacy for photography's potential was also supported by the work of colleagues like Walter Peterhans, who later headed the photography workshop at the Bauhaus.

Beyond the Bauhaus: Exile and New Beginnings

The rise of the Nazi regime in Germany brought an end to the Bauhaus experiment in 1933 and forced many of its key figures, including Moholy-Nagy, into exile due to their avant-garde practices and, in his case, Jewish heritage. He initially moved to Amsterdam, where he continued to work in commercial design, photography, and typography. His versatility allowed him to adapt, applying his modernist principles to advertising and exhibition design.

Subsequently, he relocated to London in 1935. During his time in England, he continued his photographic and design work, contributing to documentary films and interacting with British artists and intellectuals. He worked on special effects for Alexander Korda's film Things to Come and collaborated on projects with figures like the writer and film theorist Ivor Montagu and the photographer Wolfgang Suschitzky. Despite finding some success, the opportunities in London were somewhat limited compared to the vibrant atmosphere he had known in Berlin and Dessau.

The next chapter unfolded in 1937 when Moholy-Nagy accepted an invitation to move to Chicago and establish a new design school modeled on Bauhaus principles. This marked a significant turning point, offering him the chance to fully implement his educational philosophy in a new context and contribute to the development of American modernism. His journey reflected the broader diaspora of European avant-garde talent that enriched the cultural landscape of the United States during this tumultuous period.

The New Bauhaus in Chicago: Transplanting Ideals

Arriving in Chicago, Moholy-Nagy founded the "New Bauhaus: American School of Design" under the sponsorship of the Association of Arts and Industries. His mission was clear: to transplant the experimental, interdisciplinary spirit of the German Bauhaus to American soil, training designers equipped to meet the needs of modern industry and society. The school opened its doors in 1937, attracting students eager to engage with its progressive curriculum.

The New Bauhaus emphasized a hands-on approach, starting with a revised Vorkurs (preliminary course) focused on exploring materials, tools, and fundamental design principles. Workshops covered areas like light, photography, weaving, wood, metal, and plastics. Moholy-Nagy stressed the importance of sensory experience, experimentation, and understanding the inherent properties of materials. He aimed to cultivate not just technical skill but also intellectual curiosity and a holistic understanding of design's role in life.

Despite initial enthusiasm, the school faced financial difficulties and closed after only a year. Undeterred, Moholy-Nagy reopened it in 1939 as the School of Design, which later evolved into the renowned Institute of Design (ID) in 1944 (now part of the Illinois Institute of Technology). He gathered a dedicated faculty, including figures like Gyorgy Kepes, who had also worked with him earlier. Throughout these years, Moholy-Nagy tirelessly championed his vision, refining the curriculum and fostering an environment of innovation. His final major theoretical work, Vision in Motion, published posthumously in 1947 and compiled with the help of his second wife, Sibyl Moholy-Nagy, summarized his mature educational philosophy and his belief in the integration of art, science, and technology for the betterment of humanity.

A Diverse Practice: Painting, Sculpture, Design

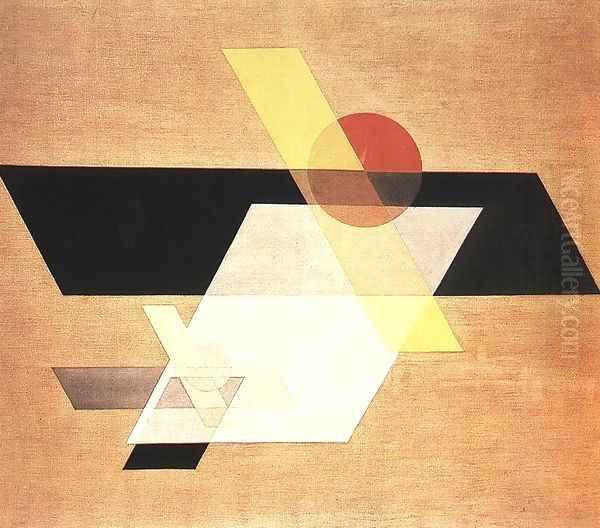

While renowned for his photographic innovations and educational leadership, Moholy-Nagy maintained a prolific and diverse artistic practice throughout his career. His work spanned painting, sculpture, typography, stage design, film, and commercial art, all unified by an experimental ethos and a consistent exploration of light, space, material, and perception. His paintings evolved from early figurative and Expressionist influences towards pure abstraction, often characterized by geometric forms, overlapping planes, and a dynamic sense of balance, as seen in works like Composition A.XX (1924).

He famously experimented with unconventional methods, such as his "Telephone Pictures" (1923), where he ordered enamel paintings from a factory sign-painter over the phone using graph paper and a color chart, exploring ideas of industrial production, authorship, and the demystification of the artistic process. His sculptures moved beyond static objects towards incorporating light and transparency, particularly through his pioneering use of plastics like Plexiglas in the later Chicago years. These works often involved incised lines and subtle coloration, playing with refraction and reflection.

Moholy-Nagy also applied his talents to practical design fields. He created innovative typography and graphic design for books, posters, and advertisements, utilizing asymmetrical layouts, sans-serif fonts, and integrated photography. His stage designs, such as sketches for a Mechanical Eccentric or designs for productions like The Tales of Hoffmann, envisioned dynamic, multi-sensory theatrical experiences incorporating light projections and moving elements. Even his commercial work retained a sense of modernist clarity and experimentation, demonstrating his belief that good design principles could permeate all aspects of life. His broad approach sometimes led to discussions with other leading designers, like Paul Rand, about the scope and meaning of design in the modern era. While distinct from the styles of Old Masters like Rembrandt or Van Gogh, his deep understanding of light and composition perhaps reflects a foundational awareness of art history absorbed during his education.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

László Moholy-Nagy's career was tragically cut short when he died of leukemia in Chicago on November 24, 1946, at the age of 51. Despite his relatively short life, his impact on modern art, design, and education was profound and multifaceted. He remains a key figure in the history of the Bauhaus and its transmission to the United States, where the Institute of Design continued to flourish and influence generations of designers and photographers.

His relentless experimentation across media solidified his status as a pioneer of multimedia and interdisciplinary art. His work with photograms, photomontage, kinetic sculpture, and abstract film broke new ground, expanding the definition of artistic practice. The concept of the "New Vision" fundamentally altered the course of modern photography, encouraging photographers to explore the unique perceptual possibilities of the camera. His Light Space Modulator is considered a seminal work of kinetic art.

Moholy-Nagy's greatest legacy, perhaps, lies in his holistic vision of integrating art, technology, and life. He believed passionately that creativity was not limited to artists but was a fundamental human capacity that could be nurtured through education. He advocated for an art that engaged with the realities of the modern industrial world, seeking not to reject technology but to harness its potential for humanistic ends. His writings, particularly The New Vision and Vision in Motion, remain vital texts for understanding modernist theory and design education. His work continues to be celebrated in major exhibitions worldwide, including retrospectives at institutions like the Tate Modern, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, reaffirming his enduring relevance.

Conclusion

László Moholy-Nagy was more than an artist; he was a visionary catalyst who constantly pushed boundaries and questioned conventions. His journey from wartime Hungary to the heart of the Bauhaus and finally to the founding of a new design institution in America encapsulates a remarkable commitment to innovation. Through his diverse body of work – encompassing painting, sculpture, photography, film, design, and influential theoretical writings – he championed an integrated approach where art and technology served a common goal: to enhance human perception and enrich modern life. His legacy endures not only in his iconic creations but also in his unwavering belief in the power of experimentation and education to shape a better future.