The annals of German art boast many luminaries, yet few figures remain as shrouded in mystery and inspire such visceral reactions as the painter known to posterity as Matthias Grünewald. Active during the turbulent cusp of the Northern Renaissance and the Protestant Reformation, this artist created works of unparalleled emotional intensity and spiritual depth. His true identity, Mathis Gothardt Neithardt, was obscured for centuries by a historical misnomer, adding another layer to the enigma surrounding his life and oeuvre. Despite the limited documentation concerning his biography, his surviving works, particularly the monumental Isenheim Altarpiece, secure his position as one of the most powerful and individualistic painters of his time.

The Riddle of the Name

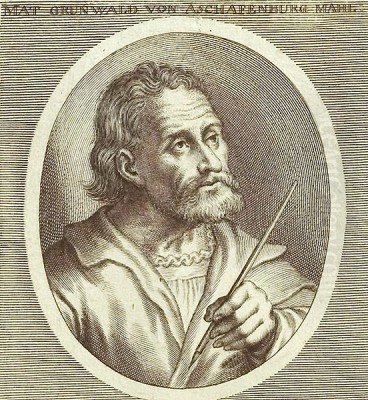

For centuries, the artist responsible for the harrowing Isenheim Altarpiece was known almost exclusively as Matthias Grünewald. This name originates from the influential 17th-century German painter and art historian Joachim von Sandrart. In his seminal work, Teutsche Academie der Edlen Bau-, Bild- und Mahlerey-Künste (German Academy of the Noble Arts of Architecture, Sculpture, and Painting), published in 1675, Sandrart praised the artist's work but mistakenly assigned him the name "Grünewald." There is no contemporary evidence to support this name, and it appears to be Sandrart's invention or the result of confusion.

It was not until the late 19th and early 20th centuries that meticulous archival research began to uncover the artist's actual identity. Documents revealed his name as Mathis Gothardt, often accompanied by "Neithardt" or variations thereof. Contracts, official records, and inscriptions, though scarce, consistently point to this name. "Mathis" is a common German form of Matthew. "Gothardt" is generally believed to be his primary surname, possibly a patronymic (derived from his father's name).

The addition of "Neithardt" (sometimes spelled Nithart, Nithardt) presents further questions. It might have been his mother's family name, or perhaps the surname of his wife, Anna Neithardt, which he occasionally adopted, a practice not entirely uncommon at the time. Some documents refer to him simply as "Maler Mathis" (Mathis the Painter). Regardless of the precise configuration, Mathis Gothardt Neithardt is now accepted by scholars as the artist's correct name, though the traditional "Grünewald" persists in popular usage due to its long history. This initial confusion set the stage for a life story pieced together from fragments and shadowed by uncertainty.

A Life Pieced from Fragments

Pinpointing the exact details of Mathis Gothardt Neithardt's life remains a challenge for art historians. His birth date is generally estimated to be between 1470 and 1480, likely placing his origins in the Franconian city of Würzburg, then part of the Prince-Bishopric of Würzburg. Little is known about his early training, though stylistic analysis suggests familiarity with the works of earlier German masters, perhaps including Martin Schongauer, whose engravings were widely circulated.

By the early 16th century, Mathis appears as an established master. Around 1504-1505, he created the intense and emotionally charged Mocking of Christ, now housed in the Alte Pinakothek in Munich. This early work already displays the hallmarks of his style: dramatic lighting, expressive figures, and a focus on suffering. He seems to have established a workshop and gained significant commissions, indicating a growing reputation.

A significant portion of his known career was spent in the service of the powerful Archbishops of Mainz. He worked initially for Uriel von Gemmingen, Prince-Elector and Archbishop of Mainz, likely residing and working primarily in Aschaffenburg, one of the Archbishop's main residences. During this period, he undertook various projects, not limited to painting. Records indicate he also possessed skills as an architect, decorator, and hydraulic engineer, overseeing fountain construction and other works at the Aschaffenburg palace.

His most famous work, the Isenheim Altarpiece, was created during this phase, likely between 1512 and 1516. This monumental commission came not directly from the Archbishop but from the Antonite monastery in Isenheim, Alsace. Following Archbishop Uriel von Gemmingen's death in 1514, Mathis continued, at least for a time, in the service of his successor, the young and ambitious Albrecht von Brandenburg. A notable work from this later period is The Meeting of Saint Erasmus and Saint Maurice (c. 1517-1523), where the figure of Saint Erasmus is widely believed to be a portrait of Albrecht.

Around 1519, Mathis married Anna Neithardt in Aschaffenburg. Sources suggest she was a converted Jewess, and some accounts hint at an unhappy union, though details are scarce. His association with Albrecht von Brandenburg seems to have ended by 1526. The reasons are debated, but his potential sympathies with the burgeoning Lutheran movement and the Peasants' War (1524-1525) are often cited as possible factors contributing to his departure from the Archbishop's court.

After leaving Aschaffenburg, Mathis moved first to the bustling mercantile city of Frankfurt. His final years were spent in Halle an der Saale, a city deeply embroiled in the religious conflicts of the Reformation and under the nominal rule of Albrecht von Brandenburg (though Albrecht spent little time there). In Halle, Mathis seems to have worked not primarily as a painter but possibly as a hydraulic engineer or even a soap boiler, according to inventories taken after his death. He died in Halle, likely in August 1528, possibly a victim of the plague. An inventory of his possessions listed Lutheran pamphlets and tracts, further fueling speculation about his religious convictions.

In the Shadow of the Reformation

Mathis Gothardt Neithardt lived and worked during one of the most tumultuous periods in German history: the Protestant Reformation, initiated by Martin Luther's Ninety-five Theses in 1517. While there is no definitive proof that Mathis formally converted to Lutheranism, circumstantial evidence suggests he was sympathetic to the cause. His departure from the service of the staunchly Catholic Cardinal Albrecht von Brandenburg, a key opponent of Luther, and the discovery of Lutheran writings among his effects at the time of his death, point towards this possibility.

The era's religious fervor, social unrest (including the Peasants' War), and intense spiritual questioning undoubtedly formed the backdrop to his artistic production. While many of his major commissions, including the Isenheim Altarpiece, were for Catholic institutions and patrons, the way he depicted religious subjects resonates with the emotional intensity and focus on personal faith characteristic of the period. His art avoids the idealized beauty and classical harmony pursued by many Italian Renaissance artists and even by his German contemporary, Albrecht Dürer.

Instead, Mathis embraced a more visceral, expressive style rooted in late Gothic traditions but pushed to new extremes. His depictions of Christ's suffering are unflinchingly graphic, emphasizing physical torment and agony. This focus on the Passion could be interpreted in light of Reformation theology, which stressed Christ's sacrifice and the believer's direct, emotional connection to God. The raw humanity and vulnerability depicted in his figures, whether Christ, the Virgin Mary, or the saints, speak to a profound engagement with the spiritual anxieties and aspirations of his time.

His art does not function as overt Protestant propaganda, unlike some works by Lucas Cranach the Elder or Hans Holbein the Younger. However, its intense emotionalism, its focus on individual spiritual experience, and its departure from purely decorative or idealized forms align it with the broader cultural shifts accompanying the Reformation. He navigated a complex religious landscape, creating powerful works that transcended simple doctrinal divides, speaking instead to universal themes of suffering, faith, and redemption.

Artistic Style: A Bridge Between Worlds

Mathis Gothardt Neithardt stands as a unique figure in the landscape of Northern European art, his style defying easy categorization. While contemporary with High Renaissance masters in Italy like Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael, and German Renaissance giants like Albrecht Dürer, Mathis largely eschewed the prevailing trends towards classicism, anatomical precision based on ideal proportions, and harmonious compositions. His artistic language remained deeply rooted in the expressive traditions of late medieval German art, particularly its sculpture, yet he infused this tradition with an unprecedented psychological depth and painterly dynamism.

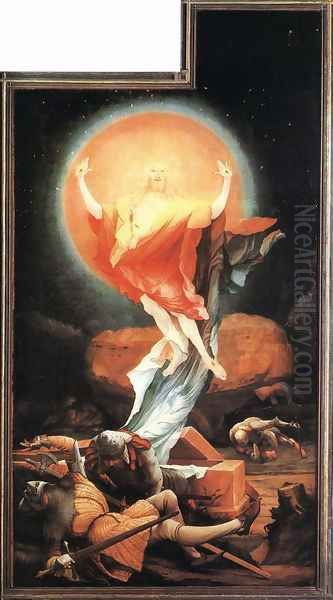

His most striking characteristic is the raw emotional power conveyed through distorted figures, dramatic gestures, and harrowing facial expressions. He did not seek idealized beauty but rather spiritual truth, often found in moments of extreme suffering or ecstatic revelation. Figures are often elongated, contorted, or wracked with pain, their bodies serving as vessels for intense inner states. This is particularly evident in his depictions of the Crucifixion, where Christ's body is shown ravaged and broken, a stark contrast to the more serene or heroic portrayals common elsewhere.

Color is fundamental to Mathis's expressive power. He employed a unique and often dissonant palette, using colors not just for description but for emotional and symbolic effect. He juxtaposed jarring hues – sickly greens, deep blacks, blood reds, and ethereal yellows – to heighten the drama and convey specific moods. His handling of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) is equally masterful and dramatic. Light often appears supernatural, either emanating from holy figures in unearthly glows or casting deep, unsettling shadows that contribute to the scene's intensity. This manipulation of light and color creates a visionary, almost mystical atmosphere in many of his works.

While rejecting Italianate classicism, Mathis was nonetheless a technically sophisticated painter. He demonstrated a keen observational skill in rendering textures – the rough wood of the cross, the delicate fabrics of robes, the decaying flesh of the crucified Christ, or the monstrous surfaces of demons. His compositions, though often asymmetrical and unsettling, are carefully constructed to guide the viewer's eye and maximize emotional impact. He stands apart from the linear precision of Dürer or the courtly elegance sometimes found in Cranach, forging a path defined by intense personal vision and profound spiritual engagement.

The Isenheim Altarpiece: A Monument of Suffering and Hope

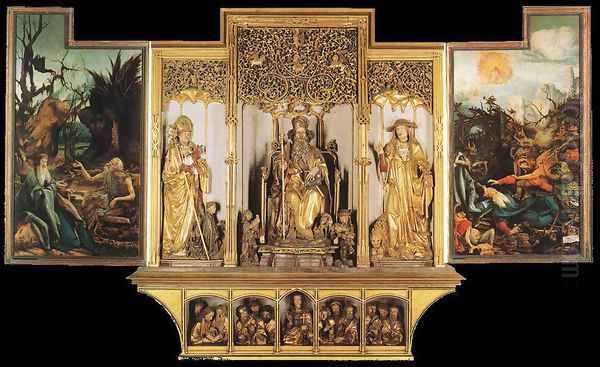

The undisputed masterpiece of Mathis Gothardt Neithardt is the Isenheim Altarpiece, created for the hospital chapel of the Monastery of St. Anthony in Isenheim, Alsace (now housed in the Musée Unterlinden, Colmar, France). The Antonite order specialized in caring for victims of plague and, particularly, skin diseases like ergotism, then known as "St. Anthony's Fire." This context is crucial for understanding the altarpiece's harrowing imagery and its intended function: to offer solace and spiritual focus to the suffering patients.

The altarpiece is a complex polyptych, a winged structure with multiple layers revealed by opening panels. In its fully closed state, visible on most days, it presents a devastatingly realistic Crucifixion. This is perhaps the most famous and shocking depiction of the event in Western art. Christ's body is grotesquely tormented, covered in sores reminiscent of ergotism, his skin greenish, his limbs contorted in agony. Flanked by a grieving Virgin Mary, supported by St. John the Evangelist, and a kneeling Mary Magdalene wringing her hands in despair, the scene is set against an ominous, dark landscape. Uniquely, St. John the Baptist stands to the right, pointing directly at Christ, accompanied by the inscription (in Latin): "He must increase, but I must decrease." Below, in the predella (base panel), lies a Lamentation over the dead Christ, equally graphic in its portrayal of death.

Opening the first set of wings reveals scenes of hope and divine intervention: the Annunciation, the Concert of Angels accompanying the Nativity, and the Resurrection. The Concert of Angels is a particularly mystical and strange scene, filled with bizarre angelic figures and an otherworldly glow surrounding the Virgin and Child. The Resurrection is a triumphant explosion of light, with Christ ascending, transfigured and radiant, leaving the tomb and startled soldiers behind. The contrast between the suffering of the outer panels and the glory of these inner scenes offered a powerful message of hope beyond earthly pain.

A further opening reveals the innermost core, a sculpted shrine (likely by Niklaus von Hagenau) featuring St. Anthony Abbot flanked by St. Augustine and St. Jerome. The painted wings accompanying this shrine are Mathis's own, depicting St. Anthony Abbot and St. Paul the Hermit in the Desert on one side, and the terrifying Temptation of St. Anthony on the other. The Temptation is a Bosch-like nightmare landscape populated by grotesque demons assaulting the saint, a direct reflection of the physical and spiritual torments endured by the hospital patients. Even here, a small figure in the corner offers a scroll with words of comfort, reinforcing the theme of faith amidst suffering.

The Isenheim Altarpiece is a work of profound theological depth and overwhelming emotional force. Its direct engagement with themes of disease, suffering, death, and redemption, tailored to its specific audience, makes it one of the most compelling and unforgettable works of religious art ever created. Its complex iconography continues to be studied and debated by scholars, revealing layers of meaning related to medieval mysticism, contemporary theology, and the human condition.

Other Notable Works

While the Isenheim Altarpiece dominates Mathis Gothardt Neithardt's legacy, several other significant works survive, showcasing the consistency of his unique vision and technical skill across different subjects and formats.

The Mocking of Christ (c. 1504-05, Munich) is considered one of his earliest surviving panel paintings. It depicts Christ blindfolded and surrounded by tormentors in a cramped, claustrophobic space. The figures are powerfully modeled, their faces contorted with malice or suffering, and the use of dramatic light and shadow already anticipates the intensity of his later works.

The Stuppach Madonna (c. 1517-1519), painted for the parish church in Stuppach, Germany, offers a different facet of his art. While still possessing a mystical quality, it depicts the Virgin Mary in an enclosed garden (hortus conclusus), a symbol of her purity. The painting is notable for its radiant color, intricate detail in the depiction of plants and objects (like a beehive and a church in the background, possibly representing the Church), and the serene yet otherworldly atmosphere surrounding the Virgin and Child.

Several panels survive from dismantled altarpieces. The Karlsruhe Crucifixion and Christ Carrying the Cross (c. 1523-25, Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe) were likely part of a larger ensemble, possibly the Tauberbischofsheim Altarpiece. They reiterate his harrowing portrayal of the Passion with intense color and emotional weight.

The Meeting of Saint Erasmus and Saint Maurice (c. 1517-23, Munich) was commissioned by Cardinal Albrecht von Brandenburg for his new collegiate church in Halle. It depicts the legendary meeting of the two saints with remarkable richness in detail, particularly in the rendering of Saint Erasmus's luxurious ecclesiastical vestments (likely a portrait of Albrecht himself) and Saint Maurice's gleaming silver armor. The work combines portrait-like realism with symbolic weight.

Fragments of the wings Mathis painted for the Heller Altarpiece (c. 1510) survive in Frankfurt and Donaueschingen. The central panel of this altarpiece was famously painted by Albrecht Dürer (now lost, known through a copy). Mathis's panels depict various saints (St. Lawrence, St. Cyriacus, St. Elizabeth of Thuringia, St. Lucy) in his characteristic expressive style, offering a fascinating contrast to Dürer's more classical approach in the same commission. These surviving works, though fewer in number than those of contemporaries like Dürer or Cranach, collectively paint a picture of an artist consistently dedicated to a deeply personal and emotionally charged form of religious expression.

Grünewald and His Contemporaries

Mathis Gothardt Neithardt worked alongside some of the most celebrated artists of the German Renaissance, yet direct records of interaction are scarce, reflecting perhaps his more solitary or geographically focused career compared to the internationally renowned Albrecht Dürer.

His most documented connection is indeed with Dürer. They collaborated, albeit separately, on the Heller Altarpiece for the Dominican church in Frankfurt around 1509-1511. Dürer painted the central panel (Assumption of the Virgin), while Mathis executed the fixed wings depicting saints. This project highlights their contrasting styles – Dürer's linear precision and Italianate influences versus Mathis's painterly intensity and Gothic expressiveness. Dürer also briefly mentions Mathis (as "Mathes") in his diary during a trip to the Netherlands in 1520. He notes showing Mathis some of his works while in Aachen for the coronation of Emperor Charles V, suggesting a professional encounter, though perhaps not a close friendship.

Compared to Lucas Cranach the Elder, another major figure of the era and a close associate of Martin Luther, Mathis's work is far less aligned with official Reformation propaganda. Cranach developed a distinct courtly style, often depicting mythological scenes or portraits alongside his religious works, whereas Mathis remained almost exclusively focused on intense religious narratives.

Other significant German contemporaries included Albrecht Altdorfer, a pioneer of landscape painting and leader of the Danube School, whose mystical landscapes offer a different kind of Northern intensity. Hans Baldung Grien, Dürer's gifted pupil, explored themes of witchcraft and the macabre with an expressiveness that sometimes echoes Mathis's intensity. The portraiture specialists Hans Holbein the Elder and his more famous son, Hans Holbein the Younger, represent another distinct path in German art, focused on realistic depiction and psychological insight within portraiture, far removed from Mathis's dramatic religious visions.

Looking beyond Germany, Mathis's work finds some parallels in the fantastical and often terrifying imagery of the Netherlandish painter Hieronymus Bosch, particularly evident in the Temptation of St. Anthony. However, Mathis's focus remains more centered on the core narratives of Christian salvation and suffering. While aware of the Italian Renaissance, his deliberate rejection of its core tenets places him in stark contrast to figures like Leonardo, Michelangelo, Raphael, or even the Venetian colorist Titian. His artistic lineage seems to trace back more strongly through late Gothic German masters like Martin Schongauer and the expressive sculptors of the period, whose work he transformed through his unique painterly genius.

Rediscovery and Legacy

Following his death in 1528, Mathis Gothardt Neithardt faded into relative obscurity for nearly three centuries. While Joachim von Sandrart kept his memory alive in the 17th century, albeit under the wrong name, his work was largely overshadowed by the fame of Dürer and Holbein. Many of his paintings were lost or misattributed. His intense, sometimes disturbing style did not align well with the classical tastes of the Baroque and Neoclassical periods.

The rediscovery and reappreciation of "Grünewald" began in the late 19th century, fueled by a growing interest in national artistic heritage and a reaction against academic classicism. Art historians began to untangle the confusion surrounding his name and oeuvre, recognizing the unique power of works like the Isenheim Altarpiece. The French novelist Joris-Karl Huysmans's influential decadent novel Là-bas (1891) featured a powerful description of the Isenheim Crucifixion, bringing the artist to the attention of a wider cultural audience.

His profound impact came with the rise of German Expressionism in the early 20th century. Artists like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Emil Nolde, Max Beckmann, Otto Dix, and Oskar Schlemmer saw in Mathis a spiritual forefather. They were drawn to his expressive distortions, his bold use of color for emotional effect, his unflinching depiction of suffering, and his perceived embodiment of a uniquely "Germanic" or "Nordic" artistic spirit, distinct from Mediterranean classicism. The Isenheim Altarpiece, in particular, became an icon for the Expressionists, resonating with their own experiences of spiritual crisis and the trauma of World War I.

Painters like Beckmann directly referenced the altarpiece's compositions, while Nolde admired its raw emotional power and intense color. Paul Hindemith's opera and symphony Mathis der Maler (1934-1938) further cemented the artist's image as a figure grappling with artistic responsibility during times of social upheaval, using the Peasants' War as a backdrop. Today, Mathis Gothardt Neithardt is recognized as one of the titans of German art, his work admired for its technical brilliance, its emotional depth, and its enduring spiritual power.

Enduring Enigmas

Despite the advances in scholarship, Mathis Gothardt Neithardt remains an enigmatic figure. Many fundamental questions about his life lack definitive answers. His precise dates of birth and death, the details of his training, the full extent of his travels, and the exact nature of his religious beliefs are still debated. Why did such a powerful artist leave behind a relatively small number of surviving works compared to some contemporaries? What were the circumstances that led him to apparently abandon painting for engineering work in his final years in Halle?

The interpretation of his works, especially the Isenheim Altarpiece, also continues to generate discussion. While the general themes are clear, the specific meanings of certain symbols, the reasons behind particular stylistic choices (like the bizarre angels in the Concert), and the full extent of the iconographic program remain subjects of scholarly inquiry. The relationship between his personal life – his marriage, his service to powerful patrons, his potential financial struggles – and his artistic output is largely speculative.

His relative obscurity for centuries, contrasted with the immediate and lasting fame of Dürer, is also puzzling. Was it due to his more challenging and less easily reproducible style? His geographical focus away from major international centers? Or the turbulent religious and political climate that may have limited his opportunities or suppressed his memory? These unanswered questions contribute to the mystique surrounding the artist known as Grünewald.

Conclusion: A Voice of Unflinching Intensity

Mathis Gothardt Neithardt, the master mistakenly called Grünewald, stands as a singular voice in the history of art. Working in an era of profound change, he forged a deeply personal style that bridged the intense spirituality of the late Middle Ages with the dawning complexities of the modern era. Rejecting the fashionable classicism imported from Italy, he looked instead to his native traditions and his own inner vision, creating works of unparalleled emotional force and psychological depth.

His unflinching depictions of suffering, particularly in the Isenheim Altarpiece, are not merely exercises in horror but profound meditations on the nature of faith, pain, and redemption. Through dramatic composition, visionary color, and expressive distortion, he conveyed the extremes of human experience, from agonizing torment to ecstatic transcendence. While the details of his life remain elusive, his surviving artworks speak with an undeniable power that continues to resonate centuries later. He remains a testament to the enduring capacity of art to confront the darkest aspects of existence while simultaneously affirming the possibility of spiritual hope, leaving behind a legacy as complex, challenging, and ultimately unforgettable as the turbulent times in which he lived.