Domenikos Theotokopoulos, universally known as El Greco ("The Greek"), stands as one of the most singular and influential figures in the history of Western art. Born in 1541 on the island of Crete, then a Venetian territory known as the Kingdom of Candia, and passing away in Toledo, Spain, on April 7, 1614, his life and art traversed diverse cultural landscapes. His journey from the Byzantine traditions of his homeland through the vibrant artistic centers of Renaissance Italy to the fervent religious atmosphere of Counter-Reformation Spain forged a style so unique it defies easy categorization, yet profoundly impacted the course of modern art.

His nickname, "El Greco," was acquired during his time in Italy, a simple designation of his Hellenic origins (his full name in Greek is Δομήνικος Θεοτοκόπουλος). It stuck with him in Spain, even as he signed many of his major works with his full Greek name, often adding "Kres" (Cretan). This duality reflects the complex synthesis inherent in his art – a fusion of Eastern spirituality and Western technique, tradition and radical innovation.

Though his intensely personal and often ecstatic style led to periods of neglect following his death, El Greco was dramatically rediscovered in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Artists and critics saw in his elongated figures, electric colors, and disregard for naturalistic representation a precursor to modern artistic movements. Today, he is celebrated not just as a master of the Spanish Renaissance, but as a visionary whose work continues to resonate with contemporary audiences.

Cretan Roots and Byzantine Foundations

El Greco's artistic journey began in Heraklion, Crete. During the mid-16th century, Crete was a thriving center of post-Byzantine art, maintaining the traditions of icon painting long after the fall of Constantinople. Young Domenikos trained in this tradition, mastering the stylized forms, non-naturalistic perspective, and spiritual intensity characteristic of Byzantine icons. These early years instilled in him a focus on the transcendental and the symbolic, elements that would remain foundational throughout his career, even as he absorbed Western influences.

Evidence suggests he was already a recognized master painter in Crete before leaving the island around the age of 26. Works from this period, though few survive definitively, show his proficiency in the established Byzantine style. However, the ambition to engage with the dynamic artistic developments unfolding in Italy likely spurred his departure. Crete, under Venetian rule, provided a natural bridge to the Italian mainland.

The Venetian Transformation: Color and Light

Around 1567, El Greco moved to Venice, the heart of a vibrant artistic school renowned for its emphasis on color (colorito) and light. This was a pivotal moment. He entered a world dominated by aging masters like Titian and the prolific Tintoretto, along with others like Paolo Veronese and the Bassano family. While direct documentation of apprenticeship is debated, tradition holds that he studied in Titian's workshop, absorbing the lessons of Venetian High Renaissance painting.

In Venice, El Greco encountered a radically different approach to art compared to the linear, symbolic style of Byzantine icons. He learned the Venetian techniques of rich oil glazes, dramatic chiaroscuro (contrast of light and dark), dynamic compositions, and the expressive potential of vibrant color. The influence is evident in the increased naturalism, richer textures, and more fluid brushwork that began to appear in his paintings. He started integrating Western elements like perspective and anatomical understanding, though always filtered through his unique sensibility.

Works from his Venetian period, or shortly after, demonstrate this transition. He began painting portraits and complex narrative scenes, adopting Venetian compositional structures while retaining a certain intensity that set him apart. The emphasis on capturing emotional states and spiritual fervor, rather than mere physical likeness, remained paramount.

Roman Interlude: Mannerism and Intellect

Seeking further development and perhaps patronage, El Greco traveled to Rome around 1570. Here, he encountered the legacy of the High Renaissance masters Michelangelo and Raphael, whose monumental works dominated the city. Rome was also a center of Mannerism, a style characterized by artificiality, elegance, elongated proportions, complex allegories, and subjective interpretations of reality. Artists like Federico Zuccari and Scipione Pulzone were active during his time there.

El Greco absorbed the lessons of Roman art, particularly the powerful figure drawing of Michelangelo, though he famously criticized Michelangelo's lack of color. He associated with intellectuals and patrons, notably entering the circle of Cardinal Alessandro Farnese, one of the wealthiest and most influential figures in Rome. A letter from the miniaturist Giulio Clovio recommended the young Cretan to the Cardinal as a "rare talent" and a disciple of Titian.

His time in Rome solidified his engagement with Mannerist tendencies – the elongated figures, the sometimes jarring color combinations, and the complex, often ambiguous spatial arrangements that would become hallmarks of his mature style. Works like Christ Healing the Blind show his assimilation of Italian techniques while pushing towards a more personal, expressive vision. However, Rome did not ultimately provide the major commissions he sought, perhaps due to his outspoken nature or the established competition.

Toledo: A Spiritual Home and Artistic Flourishing

In 1577, El Greco made the decisive move to Spain, settling in Toledo. This ancient city, the former capital and still the religious heart of Spain, proved to be the perfect environment for his unique talents. Toledo was a center of intense spirituality, mysticism, and intellectual life during the Counter-Reformation, a climate that resonated deeply with El Greco's artistic inclinations. He would remain there until his death in 1614.

He initially hoped to gain royal patronage from King Philip II, submitting works for the vast Escorial palace complex. While he completed paintings like The Allegory of the Holy League and The Martyrdom of Saint Maurice, his highly individual style did not fully align with the King's more conservative tastes. Philip preferred the work of artists like Juan Fernández de Navarrete or the Italians summoned to decorate the Escorial.

Despite failing to secure consistent royal favor, El Greco found ample patronage among Toledo's numerous churches, monasteries, and private citizens. He established a thriving workshop and received commissions for large altarpieces, devotional paintings, and portraits. Toledo provided him the freedom and the context to fully develop his mature style, becoming the city's preeminent artist.

The Mature Style: Synthesis and Transcendence

El Greco's mature style, developed in Toledo, represents a unique synthesis of his diverse experiences. He fused the spiritual intensity and symbolic abstraction of his Byzantine roots with the color and light of Venice and the elegant distortions of Italian Mannerism, all imbued with the fervent mysticism of Counter-Reformation Spain. His goal was not naturalistic representation but the evocation of intense spiritual states and divine realities.

Key characteristics define this period:

Elongated Figures: Human forms are often stretched vertically, appearing ethereal and dematerialized, reaching towards the heavens. This distortion enhances the sense of spirituality and emotional intensity.

Vibrant, Unnatural Color: He employed a palette of striking, often acidic colors – blues, yellows, greens, and reds – using them expressively rather than descriptively. Contrasts between cold and warm tones create visual tension and otherworldly effects.

Dynamic Light and Shadow: Light in his paintings is rarely natural; it flickers, illuminates figures dramatically, and seems to emanate from within the scene or from divine sources, creating a sense of mystical revelation.

Ambiguous Space: El Greco often rejected traditional linear perspective, creating compressed, ambiguous, or vertically oriented spaces that emphasize the spiritual realm over the terrestrial. Compositions are frequently crowded and swirling with energy.

Emotional Intensity: His figures convey powerful emotions – ecstasy, suffering, piety, awe – through dramatic gestures, facial expressions, and the overall energy of the composition.

This highly personal style was perfectly suited to the religious subjects that dominated his output, allowing him to visualize complex theological concepts and profound spiritual experiences in a way no other artist had before.

Masterpieces of Vision and Spirit

El Greco produced numerous masterpieces during his Toledan period, many of which remain in the city or are housed in major museums worldwide, including the Prado Museum in Madrid.

The Assumption of the Virgin (1577-79): One of his first major commissions in Toledo, for the high altar of Santo Domingo el Antiguo. This monumental work shows the Virgin ascending to heaven amidst swirling clouds and dynamic angels, demonstrating his mastery of large-scale composition and his blend of Venetian color with Mannerist energy.

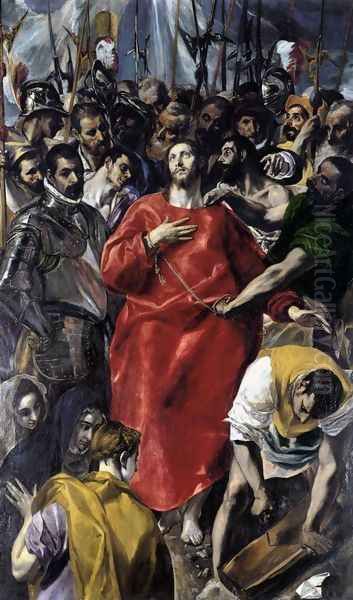

The Disrobing of Christ (El Espolio) (1577-79): Painted for the sacristy of Toledo Cathedral, this work caused controversy due to its unconventional depiction (including figures higher than Christ and the presence of the three Marys, deemed anachronistic by the Cathedral chapter). The intense focus on Christ, clad in a brilliant red robe, amidst a tumultuous crowd, showcases El Greco's dramatic power and bold color use.

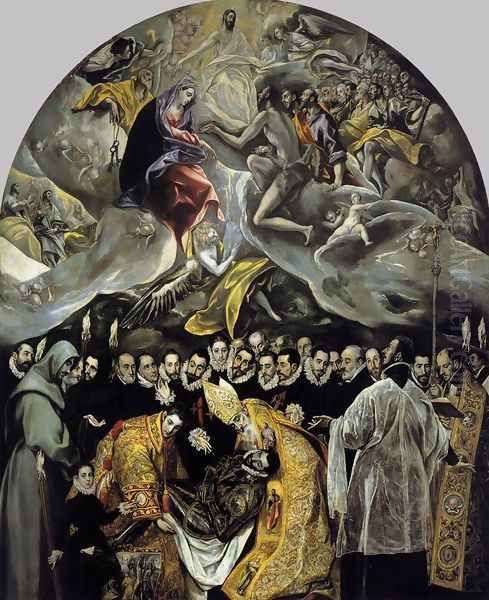

The Burial of the Count of Orgaz (1586-88): Perhaps his most famous work, painted for the church of Santo Tomé in Toledo. It depicts a local legend where Saints Augustine and Stephen descend from heaven to bury the pious Count. The painting is brilliantly divided into two zones: the terrestrial realm below, rendered with realistic portraits of Toledan society (including possibly El Greco and his son), and the celestial realm above, a swirling vortex of elongated figures, clouds, and divine light where the Count's soul is received. It is a stunning synthesis of realism and mystical vision.

Christ Driving the Money-Changers out of the Temple: El Greco painted several versions of this theme throughout his career. The later versions, particularly those from his Toledan period, are characterized by dynamic, almost violent energy, elongated figures, and dramatic architectural settings, reflecting his mature style and intense religious feeling.

These works, among many others, cemented El Greco's reputation in Toledo and showcase the power and originality of his artistic vision.

The Workshop, Pupils, and Legacy in Toledo

Like many successful artists of his time, El Greco operated a busy workshop in Toledo to meet the demand for his work. He employed assistants and trained pupils who helped produce replicas or variations of his popular compositions and assisted with large-scale commissions. This practice allowed for wider dissemination of his style, although works produced with significant workshop participation sometimes lack the full intensity of those executed entirely by the master's hand.

His most notable pupil was his son, Jorge Manuel Theotocópuli (1578–1631), who worked closely with his father and continued the workshop after El Greco's death, although his own artistic talent was more modest. Another significant follower was Luis Tristán, who absorbed much of El Greco's style but later moved towards a more naturalistic approach influenced by Caravaggio.

Despite his success with local patrons, El Greco maintained a somewhat independent status. He engaged in legal disputes over the valuation of his works, indicating a strong sense of his own worth and a willingness to challenge conventions. His intellectual circle in Toledo included prominent scholars and churchmen, suggesting he was a man of considerable learning and culture, beyond just his artistic pursuits.

Late Works: Intensified Mysticism

In his final years, El Greco's style became even more radical and expressive. His forms grew increasingly elongated and dematerialized, his brushwork looser and more flickering, and his colors even more vibrant and otherworldly. These late works possess an extraordinary spiritual intensity, often described as mystical or ecstatic.

Paintings like the Adoration of the Shepherds (1612-14), intended for his own burial chapel, exemplify this late style. The figures are dramatically elongated, bathed in an eerie, supernatural light emanating from the Christ child. The composition is filled with dynamic movement and intense emotion, conveying the miraculous nature of the event with visionary power.

The Opening of the Fifth Seal (c. 1608-1614), likely part of a larger, unfinished altarpiece, is perhaps his most abstract and visionary work. It depicts souls receiving white robes, rendered with astonishingly free brushwork, distorted figures, and a sense of apocalyptic fervor. This painting, in particular, has been seen as a direct precursor to 20th-century Expressionism and Cubism.

These late works reflect El Greco's deep personal piety and his immersion in the mystical spirituality prevalent in Toledo, associated with figures like Saint Teresa of Ávila and Saint John of the Cross. He pushed the boundaries of painting to express transcendental experiences beyond the limits of naturalistic representation.

The Distortion Debate: Astigmatism or Artistic Choice?

The distinctive elongation of figures in El Greco's work has led to speculation about its origins. In the early 20th century, the ophthalmologist Germán Beritens proposed that El Greco suffered from astigmatism, a visual defect that could cause objects to appear stretched. This theory gained some popular traction as a seemingly scientific explanation for his unique style.

However, most art historians and critics have rejected the astigmatism theory. They argue that if El Greco saw the world elongated, he would also have perceived his canvas and his own painted figures as elongated, effectively canceling out the distortion in the final product. Furthermore, he was capable of conventional representation when he chose, as seen in some of his portraits. The elongation also varies in degree and is applied selectively, suggesting it was a deliberate artistic device.

The consensus today is that El Greco's distortions were a conscious stylistic choice, rooted in Mannerist aesthetics and Byzantine traditions, and employed for expressive and spiritual purposes. The elongation enhances the sense of spirituality, dematerializes the figures, and directs the viewer's gaze upwards, aligning with the religious themes of transcendence and divine connection.

Connections (or Lack Thereof) with Contemporaries

While El Greco was active during a rich period of European art, documented direct interactions with some of the most famous painters often considered his contemporaries, like Diego Velázquez or Peter Paul Rubens, are non-existent. Chronology and geography largely precluded significant contact.

Velázquez (1599-1660) was only a teenager when El Greco died. While Velázquez, later in his career as court painter in Madrid, would certainly have encountered El Greco's works, particularly those in the royal collections or in Toledo, there is no record of personal interaction, nor is El Greco's influence strongly apparent in Velázquez's predominantly naturalistic style. Any suggestion that Velázquez influenced El Greco is chronologically impossible.

Rubens (1577-1640) did visit Spain, notably Madrid, where he interacted with the court and befriended the young Velázquez. However, El Greco was based in Toledo, and there is no evidence that Rubens sought him out or that they ever met. Their artistic paths and circles were largely separate.

El Greco's significant artistic dialogue was primarily with the artists whose work he encountered directly: the Byzantine icon painters of Crete, the Venetian masters Titian and Tintoretto, and the Central Italian figures like Michelangelo and Raphael, as well as various Mannerist painters. His legacy lies less in direct personal connections with Spanish Baroque masters and more in the profound, delayed impact his unique vision had on later generations.

From Obscurity to Modern Icon

Following his death, El Greco's reputation faded. While appreciated by some connoisseurs, his style fell out of fashion during the Baroque period, which favored greater naturalism (like Velázquez) or dramatic dynamism (like Rubens). For centuries, he was often dismissed as eccentric or even incompetent, his distortions misunderstood. Antonio Palomino, an influential 18th-century Spanish painter and writer, described him as talented but extravagant, suggesting his later style was a deliberate ploy for originality.

The rediscovery began in the 19th century, fueled by Romanticism's interest in individualism and national identity. Spanish artists and intellectuals began to re-evaluate their artistic heritage. French artists and critics traveling in Spain, like Édouard Manet and Théophile Gautier, were struck by his originality. By the late 19th century, artists like Paul Cézanne were known to admire his work.

The true rehabilitation occurred in the early 20th century. The 1902 exhibition of his work at the Prado Museum in Madrid was a landmark event. Art historians like Manuel Bartolomé Cossío published seminal studies, and German critic Julius Meier-Graefe hailed him as a prophet of modern art. Artists of the avant-garde saw in El Greco a kindred spirit who prioritized subjective expression over objective reality.

Influence on Modern Art: A Visionary Forefather

El Greco's impact on modern art is immense and multifaceted. His liberation of color, distortion of form, and emphasis on emotional and spiritual expression resonated deeply with artists seeking to break from academic naturalism.

Expressionism: His intense emotionalism, non-naturalistic color, and distorted figures directly anticipated the goals of Expressionist movements in Germany and elsewhere. Artists like Franz Marc and August Macke were profoundly influenced.

Cubism: Pablo Picasso, a fellow Spaniard, considered El Greco a crucial influence. The fragmented planes, ambiguous space, and structural analysis of form in works like Opening of the Fifth Seal have been seen as precursors to Cubist experiments. Picasso's Les Demoiselles d'Avignon shows clear affinities with El Greco's late figures.

Surrealism: The dreamlike, irrational quality of El Greco's compositions and his exploration of the subconscious and spiritual realms appealed to Surrealist sensibilities.

Other Modern Masters: Artists as diverse as Jackson Pollock, Amedeo Modigliani, Chaïm Soutine, and Francis Bacon have acknowledged or shown the influence of El Greco's unique handling of paint, form, and psychological intensity.

His work demonstrated that art could be a vehicle for profound inner experience, paving the way for many of the key developments in modern art. He showed that deviation from visual reality could lead to a deeper, more potent form of truth.

Conclusion: An Enduring Enigma

El Greco remains a towering figure in art history, a master whose work defies simple labels. He was a product of diverse cultural currents – Byzantine Crete, Renaissance Venice and Rome, Counter-Reformation Spain – yet he synthesized these influences into something entirely new and intensely personal. His art bridges the spiritual intensity of the East with the technical innovations of the West, the traditions of the past with a vision that startlingly anticipates the future.

For centuries, his genius was obscured by changing tastes, his unique style misunderstood. But his dramatic rediscovery secured his place as not only a giant of Spanish art but also a crucial forerunner of modernism. His elongated figures reaching towards the divine, his electrifying colors, and his canvases pulsating with spiritual energy continue to captivate and inspire, confirming El Greco's status as an artist of enduring power and relevance. His journey from Cretan icon painter to Toledan visionary remains one of the most fascinating narratives in the history of art.