Giovanni di Paolo di Grazia (c. 1398/1403 – 1482) stands as one of the most distinctive and imaginative painters of the Sienese School during the Italian Quattrocento, the 15th century. Active primarily in his native Siena, a city with a rich artistic heritage that often favored decorative grace and spiritual intensity over the burgeoning scientific naturalism of Florence, Giovanni di Paolo carved a unique niche for himself. His works are celebrated for their vibrant, often unconventional color palettes, their dynamic and sometimes unsettling compositions, and a deeply personal, dreamlike quality that infuses his religious narratives with an otherworldly atmosphere. Though his fame was somewhat eclipsed after his death, the 20th century saw a significant re-evaluation of his contributions, recognizing him as a profoundly original artist whose vision pushed the boundaries of Sienese tradition.

The Artistic Crucible of Siena: Early Life and Influences

Born in Siena around the turn of the 15th century, Giovanni di Paolo's early life and training are not extensively documented, a common reality for many artists of this period. However, the artistic environment of Siena itself was a powerful formative influence. Sienese painting, with luminaries like Duccio di Buoninsegna, Simone Martini, and the Lorenzetti brothers (Ambrogio and Pietro) in the preceding century, had established a strong tradition characterized by elegant lines, rich colors, a certain Byzantine hieraticism, and a profound devotional sentiment. This Sienese Gothic style, with its emphasis on decorative beauty and emotional expression, formed the bedrock of Giovanni's artistic education.

It is widely believed that Giovanni di Paolo may have received early training or been significantly influenced by Sienese masters active in the early 15th century. Figures such as Taddeo di Bartolo, a prolific painter known for his narrative cycles and robust figures, are often cited. Taddeo's workshop was a major force in Siena, and his impact on younger artists would have been considerable. Another Sienese painter, Benedetto di Bindo, known for his work on the frescoes in the sacristy of the Siena Cathedral, also likely played a role in shaping the artistic landscape Giovanni inherited.

A pivotal moment for Sienese art, and likely for Giovanni di Paolo, was the presence of the Umbrian master Gentile da Fabriano in Siena around 1425-1426. Gentile was a leading exponent of the International Gothic style, a courtly and sophisticated manner characterized by flowing lines, exquisite detail, and a rich tapestry-like effect. His masterpiece, the Adoration of the Magi (now Uffizi, Florence), though painted for Florence, epitomizes this style. Gentile's brief Sienese sojourn, during which he worked on a (now lost) altarpiece for the Notai, or public notaries, undoubtedly exposed local artists, including Giovanni, to the latest currents in Italian painting. Echoes of Gentile's refined elegance and decorative sensibility can be discerned in Giovanni's earlier works, though Giovanni would soon transform these influences into something uniquely his own.

Forging a Personal Vision: Stylistic Development and Characteristics

Giovanni di Paolo's artistic career began to gain traction in the 1420s. His earliest documented commission is the Branchini Altarpiece of 1427, painted for the Branchini family chapel in the church of San Domenico, Siena. While parts of this polyptych are now dispersed (the central panel, Virgin and Child with Angels, is in the Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena), it already showcases elements of his developing style: elongated figures, a certain intensity of expression, and a vibrant use of color.

Throughout his long career, Giovanni di Paolo demonstrated a remarkable capacity for stylistic evolution while retaining a core set of personal characteristics. His art is often described as having a "dreamlike" or "surreal" quality. This is achieved through several means: his figures, often slender and elongated, can appear to float or move with an ethereal grace that defies naturalistic constraints. His landscapes are rarely mere backdrops; instead, they become active participants in the narrative, often featuring fantastical rock formations, checkered fields that tilt and undulate in defiance of conventional perspective, and skies filled with radiant, sometimes unsettling, light.

His use of space is particularly innovative and idiosyncratic. While aware of the principles of linear perspective being developed in Florence by artists like Filippo Brunelleschi and Masaccio, Giovanni di Paolo often chose to employ a more symbolic or expressive spatial construction. He could create deep, receding landscapes when the narrative demanded it, but he was equally comfortable with flattened, decorative spaces or multiple viewpoints within a single scene, reminiscent of earlier medieval traditions but imbued with a new dynamism. This manipulation of space contributes significantly to the otherworldly feel of his paintings.

Color is another hallmark of Giovanni's art. He favored bright, often jewel-like hues, and was not afraid to use color for emotional or symbolic effect rather than purely naturalistic representation. His later works, in particular, can feature colder, more acidic color combinations and stark contrasts, heightening the drama and emotional intensity of his subjects. This expressive use of color, combined with his distinctive figural style and spatial inventions, sets him apart from many of his Sienese contemporaries, such as the more consistently lyrical Sassetta (Stefano di Giovanni) or the prolific and somewhat more conventional Sano di Pietro, who was, according to some evidence, a student or associate of Giovanni.

Masterpieces of Panel Painting

Giovanni di Paolo was a prolific painter of altarpieces and smaller devotional panels. His subjects were predominantly religious, drawn from the life of Christ, the Virgin Mary, and numerous saints, particularly those with strong Sienese connections like St. Catherine of Siena and St. Bernardino.

One of his most famous and captivating works is the small panel The Creation of the World and the Expulsion from Paradise (c. 1445, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York). This predella panel, likely from a larger altarpiece, depicts God the Father as a dynamic, bearded figure propelling a zodiacal sphere representing the cosmos, while to the right, Adam and Eve are driven from a lush, flowery Eden by an angel. The swirling energy of the creation scene and the poignant despair of the expulsion are rendered with Giovanni's characteristic imaginative flair and vibrant color. The map-like depiction of the known world within the sphere is a fascinating detail.

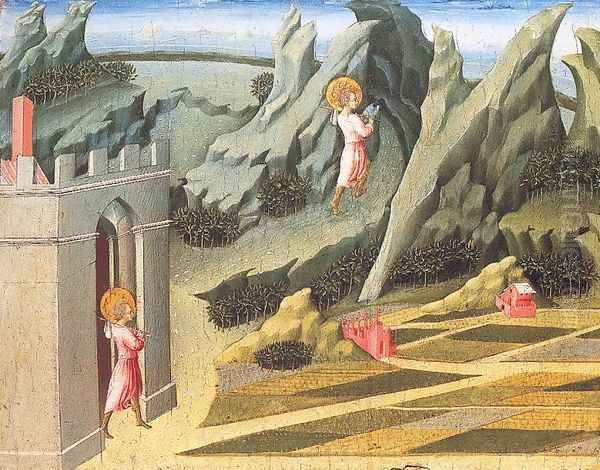

Another significant series of panels illustrates scenes from the life of St. John the Baptist, created around 1447-1449 (dispersed, with panels in the National Gallery, London, and other collections). Works like St. John the Baptist Retiring to the Desert (National Gallery, London) showcase his mastery of landscape. The saint, a small figure in a vast, undulating, and meticulously patterned terrain, moves through a world that is both recognizable and strangely abstracted. The checkered fields, a recurring motif in Giovanni's work, create a sense of rhythmic movement and decorative patterning that transcends mere topography.

The Presentation of Christ in the Temple (c. 1435, Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena) is another key work, demonstrating his ability to infuse traditional iconographic themes with fresh energy. The architectural setting is complex, and the figures, while retaining Sienese elegance, possess a heightened emotionalism. The interaction between the figures, particularly the tender gaze between the Virgin and the Christ Child, is rendered with sensitivity.

His later works, such as the panels depicting Paradise, Hell, and The Last Judgment (c. 1465, Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena), show a shift towards a more dramatic and sometimes starker style. The figures can become even more attenuated, and the colors take on a colder, more intense quality. His depictions of Hell, in particular, are filled with grotesque demons and tormented souls, rendered with a vivid, almost hallucinatory imagination that draws on medieval precedents but is filtered through his unique artistic lens.

Giovanni also undertook commissions for cassoni (marriage chests), such as the Venus Triumphant mentioned in some sources, likely for the St. Dominic's monastery, though its current whereabouts or definitive attribution can be complex to trace, as cassoni panels were often produced by workshops and their attributions can be debated by scholars.

The Art of Illumination: Dante's Divine Comedy

Beyond his panel paintings, Giovanni di Paolo was a highly accomplished manuscript illuminator. His most celebrated work in this medium is the series of illustrations he created for an edition of Dante Alighieri's Divina Commedia (Divine Comedy), commissioned by Alfonso V, King of Aragon, Naples, and Sicily, around the 1440s. The manuscript, known as the "Yates Thompson Manuscript 36," is now primarily in the British Library, London, with some detached leaves in other collections.

Giovanni's illustrations for the Paradiso section are particularly renowned. He translated Dante's celestial visions into images of breathtaking beauty and imaginative power. His depictions of Dante and Beatrice soaring through the heavenly spheres, surrounded by radiant light, angelic hosts, and geometric patterns symbolizing divine order, are among the most memorable visual interpretations of Dante's epic poem. In these illuminations, Giovanni's penchant for dreamlike atmospheres, vibrant color, and innovative spatial compositions found a perfect outlet. He was not merely illustrating the text but offering a profound visual meditation on its spiritual themes. The scenes from Inferno and Purgatorio are equally compelling, showcasing his ability to convey a wide range of human and divine experiences, from abject suffering to spiritual ascent. These illuminations underscore his intellectual engagement with complex literary and theological themes.

The Sienese Milieu: Contemporaries, Collaborators, and Competitors

Giovanni di Paolo operated within a vibrant, if somewhat conservative, artistic community in Siena. He was a contemporary of several other notable Sienese painters. Sassetta (Stefano di Giovanni) (c. 1392 – 1450/51) was perhaps the leading Sienese painter of the first half of the 15th century. Sassetta's style, characterized by its gentle lyricism, delicate figures, and harmonious color schemes, offered a contrast to Giovanni's more intense and sometimes eccentric vision. While both artists drew from the Sienese tradition and were influenced by International Gothic currents, their artistic personalities diverged, with Sassetta often seen as more refined and Giovanni as more expressive and unpredictable. There is evidence of mutual awareness and perhaps influence, as is common in close-knit artistic communities.

Sano di Pietro (1406–1481) was another highly prolific Sienese painter, whose career largely overlapped with Giovanni's. Sano's style was generally more conservative and consistent, and he ran a large and successful workshop that produced numerous altarpieces and devotional panels in a readily recognizable manner. As mentioned, some art historians suggest Sano may have had a period of association or even studentship with Giovanni, though Sano's output generally lacks the imaginative daring of Giovanni's best work.

Other Sienese painters active during parts of Giovanni's career include Pietro di Giovanni d'Ambrogio, known for his expressive figures, and later figures like Francesco di Giorgio Martini (also a renowned architect and sculptor) and Matteo di Giovanni. Francesco di Giorgio's work, in particular, shows a greater engagement with Florentine Renaissance innovations, representing a later phase of Sienese art. Matteo di Giovanni, active in the latter half of the century, also produced significant altarpieces, sometimes collaborating with other artists. The extent of direct collaboration between Giovanni di Paolo and these figures is not always clear, but they were all part of the same artistic ecosystem, competing for commissions and contributing to Siena's artistic identity. The Sienese painters' guild (Arte dei Pittori) would have provided a forum for interaction, and workshop practices often involved shared labor on large commissions.

Anecdotes and Special Events: Glimpses into a Life

Specific, well-documented anecdotes about Giovanni di Paolo's personal life are scarce, as is typical for artists of his era unless they were subjects of early biographers like Giorgio Vasari (who, incidentally, paid little attention to Giovanni). However, the nature of his commissions and the themes he depicted offer insights into his world and concerns.

His painting depicting the Mystical Marriage of St. Catherine of Siena or her mystical communion with Christ reflects the deep reverence for this local saint in Siena. St. Catherine was a powerful figure in Sienese religious life, and scenes from her hagiography were popular subjects. Giovanni's interpretations of these events would have been imbued with the intense spirituality characteristic of his work, aiming to make the mystical tangible for the viewer. One such narrative involves St. Catherine being unable to attend church but, through the intercession of her confessor, experiencing a vision of Christ in another sacred space – a theme Giovanni is recorded as having painted, emphasizing the miraculous and personal nature of faith.

His depictions of the sermons of St. John the Baptist, often set in expansive and imaginative landscapes, highlight his narrative skills. In these scenes, the wilderness becomes a character in itself, a place of spiritual testing and divine revelation. The way he positions the diminutive figure of the saint within these vast, almost abstract terrains underscores the magnitude of the spiritual journey.

The commission for the Divine Comedy illustrations for a royal patron like Alfonso V was a significant undertaking, indicating a reputation that extended beyond Siena. Such a project would have required not only artistic skill but also a degree of erudition to engage with Dante's complex allegories.

His work often seems to blend religious devotion with a philosophical, almost metaphysical, contemplation of the world. The Expulsion from Paradise, for instance, with its meticulously rendered, albeit stylized, flora in Eden, juxtaposed with the barrenness outside, speaks to profound themes of loss, innocence, and the human condition. The symbolic use of plants and the expressive postures of Adam and Eve convey a deep emotional and intellectual engagement with the biblical narrative.

Later Career and Evolving Vision

Giovanni di Paolo remained active into his old age, with documented works spanning into the 1470s. His later style, as seen in works like The Assumption of the Virgin (c. 1475, Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena), continued to evolve. While some scholars detect a hardening of line or a certain repetition of motifs in his very late works, which might indicate increased workshop participation, his distinctive artistic personality remained evident. The colors could become even more stark, and the figures sometimes took on an almost brittle quality, but the intensity of expression and the imaginative power were often still present.

His willingness to experiment with composition and color, even late in his career, speaks to a restless artistic intellect. He was not an artist who settled into a comfortable formula but continued to explore the expressive possibilities of his medium. This persistent individuality is perhaps one reason why his work stood out, and also why it may have been perceived as somewhat eccentric by contemporaries accustomed to more conventional styles.

Legacy and Rediscovery: An Enduring Influence

Despite a long and productive career, Giovanni di Paolo's fame seemed to wane considerably after his death in 1482. He was largely overlooked by later art historians, including Vasari, whose Lives of the Artists privileged the Florentine school and its development towards High Renaissance naturalism. Giovanni's style, with its lingering Gothic elements, its expressive distortions, and its often anti-naturalistic tendencies, did not fit neatly into this teleological narrative of artistic progress.

It was not until the late 19th and, more significantly, the 20th century that Giovanni di Paolo's work began to be seriously re-evaluated. Art historians and critics, including figures like Bernard Berenson, John Pope-Hennessy, and Millard Meiss, played crucial roles in rediscovering his unique genius. They recognized in his art a powerful and original voice, one that offered a compelling alternative to the mainstream developments of the Florentine Renaissance.

His imaginative, dreamlike qualities, his expressive use of color and line, and his often unsettling compositions resonated with modern sensibilities, particularly with the rise of Expressionism and Surrealism. Artists and critics saw in Giovanni a precursor, an artist who prioritized inner vision and emotional intensity over strict adherence to naturalistic representation. His work was no longer seen as merely provincial or retardataire but as a sophisticated and highly personal artistic statement.

Today, Giovanni di Paolo is considered one of the most important and fascinating painters of the Sienese Quattrocento. His works are prized by museums and collectors worldwide, and he is the subject of ongoing scholarly research. His influence on the Sienese school was significant in his time, and his rediscovery has enriched our understanding of the diversity and complexity of Early Renaissance art in Italy. He demonstrated that the Sienese tradition, while distinct from that of Florence, was capable of producing art of profound originality and enduring power.

Conclusion: A Singular Vision in Sienese Art

Giovanni di Paolo remains a captivating figure in the history of art. His ability to synthesize the decorative elegance of the Sienese tradition with a deeply personal, often mystical, and strikingly modern-seeming vision sets him apart. From his meticulously crafted altarpieces to his visionary manuscript illuminations, his work is characterized by an intensity of feeling, a bold use of color and composition, and an imaginative power that continues to fascinate and inspire. He was an artist who dared to be different, creating a world in his paintings that is at once familiar in its religious iconography and startlingly new in its artistic execution. His legacy is a testament to the enduring power of individual artistic vision and the rich, multifaceted tapestry of the Italian Renaissance. Giovanni di Paolo was not just a Sienese painter; he was a master of dream and devotion, whose art transcends its time and place to speak to universal human experiences of faith, wonder, and the mysteries of existence.