Max Beckmann stands as one of the titans of twentieth-century German art, a painter, printmaker, sculptor, and writer whose life and work were inextricably linked to the tumultuous historical currents of his time. Born in Leipzig, Germany, in 1884 and passing away in New York City in 1950, Beckmann forged a unique artistic path. His powerful, often enigmatic images grapple with the complexities of modern existence, mythology, spirituality, and the enduring mysteries of the self. While often associated with Expressionism and later the New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit) movement, Beckmann fiercely maintained his independence, creating a visual language distinctly his own, marked by bold forms, compressed spaces, and profound symbolic depth. His journey took him from imperial Germany through the horrors of World War I, the vibrant but unstable Weimar Republic, the persecution of the Nazi regime, exile in Amsterdam, and finally, a new life in the United States.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Max Beckmann entered the world on February 12, 1884, in Leipzig, into a middle-class family. His father was a grain merchant, providing a background of relative stability that contrasted sharply with the upheavals Beckmann would later depict. His artistic inclinations emerged early, leading him to the Grand Ducal Saxon Art School in Weimar, a respected institution where he received formal training. Even during these formative years, Beckmann began a practice that would continue throughout his life: self-portraiture. At just sixteen, he started scrutinizing his own image, initiating a lifelong dialogue with the self that would yield some of his most compelling works.

The early influences on Beckmann were diverse. He absorbed the lessons of Impressionism, visible in the looser brushwork and attention to light in some of his initial pieces. However, he quickly moved beyond its focus on fleeting moments. A pivotal trip to Paris in 1903 exposed him to the revolutionary works of Post-Impressionist masters. The structural solidity of Paul Cézanne, the raw emotional intensity of Vincent van Gogh, and the psychological depth of Norwegian painter Edvard Munch all left their mark on the young artist, pushing him towards a more expressive and personally charged style.

Returning to Germany, Beckmann began to establish himself within the Berlin art scene. He associated with the Berlin Secession, a group of artists who broke away from the conservative academic establishment, seeking new forms of expression. Figures like Lovis Corinth were part of this milieu. Beckmann joined the Secession in 1907 and by 1910, his talent and ambition had earned him a position on its board. His early successes were recognized formally; in 1906, he received an honorary prize from the German Artists Association and was awarded the prestigious Villa Romana Prize for his painting Young Men by the Sea, which included a scholarship allowing him to spend time in Florence, further enriching his understanding of art history, particularly the Italian masters.

The Crucible of War

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 marked a profound and brutal turning point in Beckmann's life and art. Like many artists and intellectuals of his generation, he initially volunteered for service, perhaps caught up in the patriotic fervor or seeking intense experience. He served as a medical orderly on the front lines, primarily in Flanders. This role thrust him into the very heart of the war's industrialized carnage, exposing him daily to horrific injuries, death, and the complete breakdown of human dignity. The romantic notions of war quickly evaporated, replaced by a visceral understanding of its senseless violence and devastating psychological impact.

The trauma Beckmann witnessed and experienced proved overwhelming. In 1915, he suffered a nervous breakdown and was discharged from military service. The war had irrevocably shattered his worldview and, consequently, his artistic approach. His pre-war style, which still retained elements of late Impressionism and a certain romanticism, gave way to something far harsher, more angular, and emotionally raw. The experience fundamentally altered his perception of humanity, revealing its capacity for extreme cruelty but also its vulnerability.

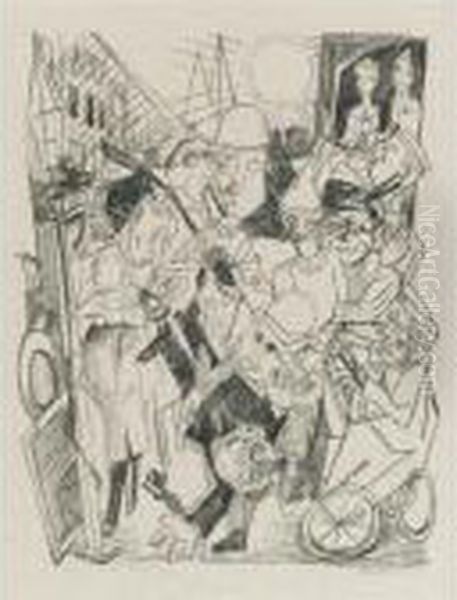

This transformation is starkly evident in the works created during and immediately after the war. His lines became thicker, blacker, often jagged, carving out forms with brutal energy. Space in his paintings became compressed, claustrophobic, reflecting the psychological pressure and confinement of the era. Figures appeared distorted, their bodies twisted and crammed into tight spaces, their faces often mask-like, conveying alienation and suffering. The themes shifted dramatically towards depictions of violence, fear, pain, and the existential dread that permeated post-war European society. His art became a testament to the "terrible cry of anguish" he felt humanity had uttered.

One of the most powerful examples of this shift is the painting The Night (1918-1919). This harrowing work depicts a scene of brutal home invasion and torture in a cramped attic room. The space is fractured, tilted, and illogical, mirroring the moral chaos and societal breakdown. Figures are contorted in agony, their limbs overlapping in a nightmarish tangle. The colors are muted and dissonant. The Night is a landmark work, often cited as a key example of the emerging New Objectivity, yet it retains the raw emotional power characteristic of Expressionism, demonstrating Beckmann's unique synthesis of styles in response to historical trauma.

The Weimar Republic and New Objectivity

The period following World War I, known as the Weimar Republic (1919-1933), was a time of intense social, political, and cultural ferment in Germany. It was an era of artistic innovation and experimentation, but also one of economic hardship, political instability, and underlying societal tension. Max Beckmann emerged as a leading figure in the art world of this period, his work capturing the anxieties and contradictions of the time. He settled in Frankfurt, where his reputation grew significantly.

In 1925, Beckmann achieved a major professional milestone when he was appointed professor at the Städelschule, Frankfurt's renowned art academy. This position solidified his status and provided him with a platform. His success was further recognized in 1927 when he received the Honorary Empire Prize for German Art and a gold medal from the city of Düsseldorf. During the 1920s, his style continued to evolve, solidifying characteristics that would define his mature work: strong black outlines reminiscent of stained glass or medieval woodcuts, flattened perspectives, symbolic use of objects, and a focus on the human figure, often in allegorical or theatrical settings.

Beckmann is often associated with the New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit) movement, which gained prominence in the mid-1920s. This movement represented a reaction against the perceived emotional excesses of Expressionism, favoring a more sober, realistic, and often bitingly critical depiction of contemporary society. Artists like Otto Dix and George Grosz were central figures, known for their unflinching portrayals of war veterans, urban decay, and social inequality. Beckmann shared their critical stance towards Weimar society and their focus on tangible reality, yet he always maintained a distance from the movement's core tenets.

![The Argonauts [right panel] by Max Beckmann](https://www.niceartgallery.com/imgs/4640952/m/max-beckmann-the-argonauts-right-panel-b478a764.jpg)

While Dix and Grosz often employed caricature and a more overtly political satire, Beckmann's critique was typically more philosophical and existential. His figures, though grounded in reality, often carried symbolic weight, hinting at deeper mythological or spiritual dimensions. He was less interested in straightforward social documentation than in exploring the human condition within the specific context of his time. Works like Family Picture (1920) depict domesticity not as a haven but as a potentially claustrophobic space filled with psychological tension. Party in Paris (1931, though sometimes dated earlier) portrays the superficial glamour and underlying alienation of modern urban life. He captured the era's unease, its mix of decadence and despair, without fully subscribing to the stylistic program of Neue Sachlichkeit.

The Triptychs: Monumental Narratives

Beginning in the 1930s, Max Beckmann turned increasingly to the triptych format – a three-paneled painting traditionally used for altarpieces in medieval and Renaissance churches. This choice was significant, lending his secular, often deeply personal themes a sense of monumental importance and spiritual weight. These large-scale works allowed him to develop complex, multi-layered narratives, weaving together personal experience, contemporary events, ancient myths, and esoteric symbolism. The triptychs represent the pinnacle of his artistic ambition and intellectual engagement.

The first and perhaps most famous of these is Departure (1932-1933). Created just as the Nazis were consolidating power, it serves as a powerful allegory of escape and transcendence amidst brutality and confinement. The two side panels depict scenes of horrific torture, bondage, and inexplicable cruelty, rendered in Beckmann's characteristic compressed space and harsh forms. These panels encapsulate the violence and barbarism Beckmann saw engulfing Germany and the world.

In stark contrast, the central panel offers a vision of liberation, though one steeped in ambiguity. It shows a regal family – a king, queen, and child – setting sail on a calm, blue sea under a bright sky. They are accompanied by a hooded figure holding a large fish. The imagery evokes ancient myths of sea journeys, quests, and perhaps the Fisher King legend. It suggests a departure from the horrors of the side panels, a journey towards self-realization or spiritual freedom, but the destination remains unknown. Departure is a profound statement about the human spirit's resilience and its capacity to seek meaning even in the darkest of times. It reflects Beckmann's own impending need to flee Germany.

Beckmann would go on to create nine more triptychs throughout his career, each exploring complex themes. Temptation (1936-1937) delves into the struggles between spirit and flesh, art and worldly distractions. The Argonauts (1950), his final completed triptych, returns to mythological themes, depicting figures embarking on a quest, suggesting a culmination or perhaps a continuation of the journey begun in Departure. These monumental works function like visual novels or philosophical treatises, inviting prolonged contemplation and resisting easy interpretation. They solidify Beckmann's place as a modern myth-maker, using ancient forms to grapple with the enduring questions of human existence in the face of twentieth-century crises.

The Shadow of Nazism and Exile

The rise of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party in 1933 brought Max Beckmann's successful career in Germany to an abrupt and devastating halt. The Nazi regime quickly implemented policies to control culture and suppress any art deemed "un-German" or challenging to their ideology. Modern art movements, including Expressionism and New Objectivity, were targeted with particular vehemence. Beckmann, as a prominent modern artist whose work often dealt with uncomfortable truths and complex psychological states, was inevitably caught in the crosshairs.

In 1933, almost immediately after the Nazis came to power, Beckmann was dismissed from his teaching position at the Städelschule in Frankfurt. His art was officially condemned as "degenerate" ("Entartete Kunst"). This label was applied broadly to art that did not conform to the Nazis' narrow, pseudo-classical aesthetic ideals and nationalist propaganda. Hundreds of his works were confiscated from German museums. The situation culminated in the infamous "Degenerate Art" exhibition staged by the Nazis in Munich in 1937. This exhibition was designed to mock and vilify modern art, and Beckmann's works were prominently featured among those by artists like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Emil Nolde, Wassily Kandinsky, and Paul Klee.

The day after hearing Hitler's radio speech denouncing modern art during the opening of the rival "Great German Art Exhibition," Beckmann and his second wife, Mathilde "Quappi" von Kaulbach (whom he had married in 1925 after divorcing Minna Tube), made the decisive choice to leave Germany for good. They fled to Amsterdam, Netherlands, intending it perhaps as a temporary stopover while seeking passage to the United States. However, the outbreak of World War II trapped them there for ten years.

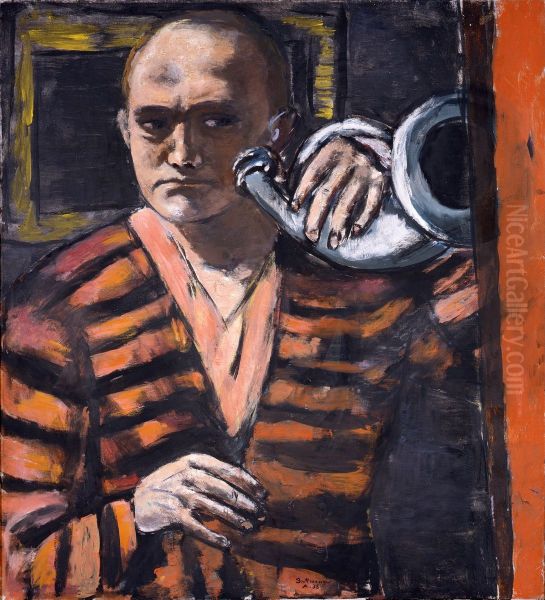

Life in Amsterdam during the German occupation was fraught with danger, uncertainty, and isolation. Beckmann lived in constant fear of discovery and deportation, unable to exhibit his work publicly. Despite these incredibly difficult circumstances, his period of exile in Amsterdam was remarkably productive. He created nearly a third of his entire life's work during these ten years, including several of his major triptychs, numerous self-portraits, and powerful allegorical paintings. Works from this period often reflect themes of confinement, disguise, mythology, and the absurdity of the human condition under duress. The cramped interiors, masked figures, and symbolic objects (like candles, fish, horns, and cages) prevalent in his Amsterdam paintings speak volumes about his psychological state and his observations of a world consumed by conflict.

Life and Work in America

Following the end of World War II, Max Beckmann finally received the necessary visa to emigrate to the United States in 1947. He arrived seeking not only safety but also a new audience and environment for his work, hoping for the recognition that had been denied him in Nazi Germany and precarious in occupied Amsterdam. His reputation had preceded him to some extent, particularly within art circles, and he quickly secured teaching positions.

His first appointment was at the School of Fine Arts at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri. He taught there for two years, influencing a generation of American students. St. Louis proved to be a relatively calm and productive environment for him after the turmoil of Europe. He found patrons and friends, including Perry T. Rathbone, director of the Saint Louis Art Museum, which already held a significant collection of his work. In 1948, Beckmann became an American citizen, formally marking his transition to a new homeland, although he always retained a complex relationship with his German roots.

In 1949, Beckmann moved to New York City to accept a teaching position at the Brooklyn Museum Art School. New York, the burgeoning center of the post-war art world, offered a different kind of energy. He lived near Central Park and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, institutions that provided both solace and inspiration. His late works, including his final triptych The Argonauts, continued to explore his characteristic themes of myth, journey, and the human drama, perhaps with a slightly brighter palette and looser brushwork compared to the Amsterdam years, but still retaining their underlying intensity and symbolic density.

Despite finding a measure of stability and recognition in the United States, Beckmann remained, in many ways, an outsider. His deeply European sensibility and complex allegorical style stood somewhat apart from the rising tide of Abstract Expressionism, championed by artists like Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning. Nevertheless, his work was exhibited, collected, and respected. His time in America represented the final chapter in a life marked by displacement and resilience. On December 27, 1950, Max Beckmann died of a heart attack in New York City, reportedly on his way to the Metropolitan Museum to see one of his own self-portraits on display.

The Enduring Power of the Self-Portrait

Throughout his life, from his teenage years until his death, Max Beckmann consistently returned to the genre of the self-portrait. He created over eighty self-portraits in various media (painting, drawing, printmaking), making it one of the most significant and revealing aspects of his oeuvre. This sustained engagement with his own image goes far beyond mere vanity; it served as a crucial tool for self-examination, a way to navigate his identity amidst personal and historical crises, and a means to explore the complex relationship between the artist, his role, and the world he inhabited.

His self-portraits chart the course of his life and artistic development. Early examples show a confident, sometimes defiant young man. The self-portraits from the World War I era and immediately after reveal the profound psychological impact of the conflict, depicting a gaunt, haunted figure marked by trauma. In the Weimar years, his self-portraits often project an image of stoic resilience and intellectual authority, such as the iconic Self-Portrait in Tuxedo (1927). Here, he presents himself as a commanding, almost confrontational figure, impeccably dressed but with a stern, unsmiling expression, asserting his presence in a world he observes with critical detachment.

During his exile in Amsterdam, the self-portraits took on new layers of meaning. Often depicted in confined spaces, sometimes holding symbolic objects like a horn or wearing disguises, these works reflect his isolation, his status as an outsider, and perhaps the need for concealment. They convey a sense of introspection, endurance, and continued artistic purpose despite adversity. The American self-portraits sometimes show a figure who seems weary but still resolute, grappling with his place in a new world.

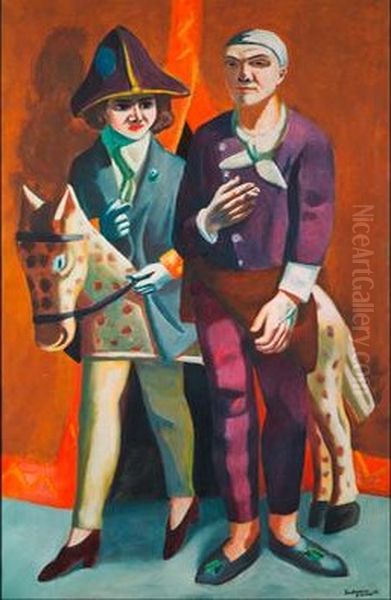

Beckmann's approach to self-portraiture differs significantly from that of artists like Rembrandt van Rijn, whose self-portraits often convey deep vulnerability and the physical marks of aging, or Vincent van Gogh, whose self-images are raw channels of emotional turmoil. Beckmann's self-portraits frequently involve a sense of performance or role-playing. He presents himself as a king, a prisoner, a clown, a prophet – using these guises to explore different facets of his identity and the human condition. They are less about revealing a singular, stable "self" and more about the artist as a witness, a survivor, and a participant in the grand, often tragic, theatre of life.

Artistic Style and Legacy

Max Beckmann's artistic style is instantly recognizable yet difficult to categorize neatly. He drew from a wide range of influences, including Northern European masters like Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Bruegel the Elder (evident in his complex narratives and crowded compositions), as well as modernists like Cézanne, Van Gogh, Munch, and even indirectly, Picasso, whose formal innovations Beckmann absorbed and transformed. While associated with Expressionism for his emotional intensity and distortion, and with New Objectivity for his engagement with social reality, he ultimately transcended both movements.

Key characteristics define his visual language. Perhaps most prominent are the thick, black outlines that delineate figures and objects, creating a powerful graphic quality reminiscent of medieval stained glass or woodcuts. This technique serves to flatten space and emphasize form. His compositions are often deliberately crowded and compressed, creating a sense of tension and claustrophobia. Figures are frequently monumental, angular, and mask-like, conveying psychological states rather than naturalistic likenesses.

Symbolism permeates Beckmann's work. Objects like fish, candles, horns, masks, mirrors, and cards appear repeatedly, carrying multiple, often ambiguous meanings related to themes of spirituality, sexuality, captivity, freedom, and the enigmatic nature of reality. His use of color is bold and often non-naturalistic, employed for emotional and symbolic effect rather than descriptive accuracy. He masterfully combined mythological or biblical references with scenes of contemporary life – cabarets, circuses, city streets – suggesting that the ancient dramas of human existence continue to unfold in the modern world.

Beckmann's legacy lies in his creation of a deeply personal yet universally resonant body of work that confronts the anxieties and complexities of the twentieth century. He stands as a crucial link between traditional figurative painting and modernism, demonstrating that representational art could still possess profound psychological depth and critical power in an era increasingly dominated by abstraction. He rejected the purely formal concerns of some abstract artists like Kandinsky, insisting on the importance of subject matter and the artist's role as a commentator on the human condition. His unflinching gaze, his technical mastery, and his profound engagement with myth and selfhood continue to influence and inspire artists today. His works are held in major museums worldwide, testament to his enduring importance as a chronicler of the modern soul.

Conclusion

Max Beckmann navigated one of history's most turbulent periods, channeling his experiences and profound intellect into an art of uncompromising power and complexity. From his early explorations influenced by Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, through the transformative trauma of World War I, his rise during the Weimar Republic, his persecution by the Nazis, and his years of exile, Beckmann forged a unique artistic identity. He was a master storyteller in paint, weaving together myth, allegory, social critique, and intense self-scrutiny. His bold forms, compressed spaces, symbolic language, and especially his monumental triptychs and searching self-portraits, offer a profound meditation on the struggles, anxieties, and enduring mysteries of human existence in the modern age. Refusing easy categorization, Beckmann remains a singular figure in twentieth-century art, a witness to history and an explorer of the timeless dramas of the soul.