Michael Pacher (circa 1435–1498) stands as a pivotal figure in the art of late medieval Central Europe, an artist whose workshop in the County of Tyrol became a crucible for the fusion of enduring Gothic traditions with the burgeoning innovations of the Italian Renaissance. Active primarily as a painter and a sculptor of wooden altarpieces, Pacher's genius lay in his ability to synthesize these seemingly disparate artistic currents, creating works of profound spiritual intensity, technical brilliance, and groundbreaking spatial illusionism. His legacy, though centered in the Alpine regions, resonated through German-speaking lands, marking him as one of the earliest and most significant artists to introduce Renaissance principles north of the Alps.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Tyrol

Born around 1435, likely near Brixen (Bressanone) or in Bruneck (Brunico) in the Puster Valley, South Tyrol – then an Austrian territory, now part of Italy – Michael Pacher's early life and training are not extensively documented, a commonality for many artists of his era. However, the artistic environment of Tyrol in the mid-15th century was vibrant, albeit still largely steeped in the International Gothic style. This style, characterized by elegant figures, rich colors, and decorative patterns, would have formed the bedrock of his initial artistic vocabulary.

It is presumed that Pacher received his foundational training locally, perhaps apprenticing in one of the many workshops that catered to the ecclesiastical and private devotional needs of the region. These workshops would have specialized in the creation of altarpieces, sculptures, and panel paintings, providing a comprehensive education in both carving and painting techniques. The influence of earlier Tyrolean masters, such as the Master of Uttenheim, can be discerned in some of Pacher's formative works, particularly in the expressive qualities of his figures and the attention to detail.

The Italian Sojourn and the Influence of the Renaissance

A defining characteristic of Pacher's art is its sophisticated engagement with Italian Renaissance principles, particularly in the realm of perspective and figural representation. While direct documentary proof of an extended Italian journey is scarce, the visual evidence within his work strongly suggests that he traveled to Northern Italy, most likely to Padua, a major artistic and intellectual center. Padua, at this time, was a hotbed of artistic innovation, home to the workshop of Francesco Squarcione, a teacher known for his collection of antiquities and his emphasis on classical forms.

More significantly, Padua was where Pacher would have encountered the revolutionary art of Andrea Mantegna (c. 1431–1506). Mantegna, himself a student of Squarcione and later court painter to the Gonzaga family in Mantua, was a master of perspective, anatomical accuracy, and a sculptural approach to painting, deeply influenced by the work of Donatello (c. 1386–1466) who had worked in Padua. Pacher's adoption of low viewpoints, dramatic foreshortening, and the illusion of figures projecting into the viewer's space are hallmarks of Mantegna's influence. The Ovetari Chapel frescoes by Mantegna in Padua, though now largely destroyed, would have been a powerful demonstration of these principles. It's also plausible Pacher encountered works by other Paduan or Venetian artists like Jacopo Bellini (c. 1400–c. 1470), Mantegna's father-in-law, or even earlier pioneers of perspective like Paolo Uccello (1397–1475) and Filippo Lippi (c. 1406–1469) through their impact on the North Italian artistic milieu.

A Unique Stylistic Synthesis: Gothic Expressionism and Renaissance Rationalism

Pacher did not simply imitate Italian models. Instead, he masterfully integrated these new ideas with the established traditions of Northern European art. His work retains the emotional intensity, the intricate detail, and the vibrant polychromy characteristic of late Gothic art, particularly the German tradition. Artists like Stefan Lochner (c. 1410–1451) in Cologne or the sculptor Nicolaus Gerhaert van Leyden (c. 1430–1473), active in Strasbourg and Vienna, exemplified this Northern expressiveness and meticulous craftsmanship.

Pacher's figures, while often placed within rationally constructed perspectival spaces, possess a dynamic energy and psychological depth that is distinctly Northern. His draperies are often complex and angular, contributing to the dramatic impact of his scenes, a feature shared with contemporary German sculptors like Veit Stoss (c. 1447–1533) and Tilman Riemenschneider (c. 1460–1531). This fusion resulted in a unique style: one that combined the intellectual rigor of Italian spatial construction with the visceral emotional appeal of Gothic art. He was, in essence, translating the humanistic concerns of the Italian Renaissance into a visual language that resonated with the spiritual sensibilities of his Alpine patrons.

Mastery in Wood and Paint: The Integrated Altarpiece

Pacher's workshop, established in Bruneck by 1467, was renowned for producing large, complex winged altarpieces (polyptychs). These multimedia constructions, often featuring a central carved shrine (Corpus) flanked by painted wings, were the primary form of monumental religious art in German-speaking lands. Pacher excelled in both the sculptural and pictorial components, and his workshop likely employed specialized assistants for various tasks, though the overarching design and key figures were undoubtedly his own.

His sculptures, typically carved from limewood or pine, were often polychromed and gilded, enhancing their lifelike presence and spiritual significance. The carving is characterized by deep undercutting, expressive faces, and dynamic poses. His painted panels demonstrate a keen understanding of oil painting techniques, allowing for rich colors, subtle gradations of light and shadow, and meticulous rendering of textures. The seamless integration of sculpture and painting within a single altarpiece structure is a hallmark of Pacher's genius, where the painted narratives on the wings would complement and expand upon the themes presented in the central sculptural shrine.

The St. Wolfgang Altarpiece: A Monumental Achievement

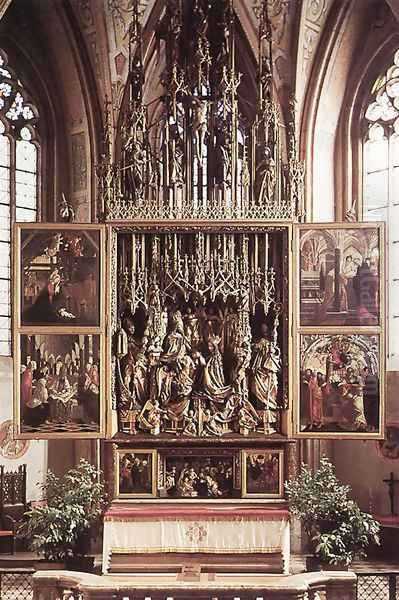

The most celebrated and best-preserved of Pacher's works is the St. Wolfgang Altarpiece, created between 1471 and 1481 for the pilgrimage church of St. Wolfgang im Salzkammergut in Austria. This monumental polyptych is a testament to his artistic vision and technical prowess. The contract for this altarpiece, dated 1471, still exists and specifies the materials and iconography.

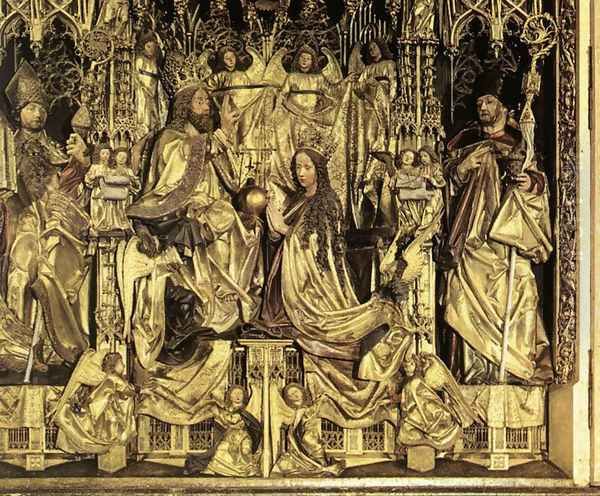

When fully open, the altarpiece reveals a magnificent central shrine depicting the Coronation of the Virgin, a deeply carved and lavishly gilded scene populated by dynamic, expressive figures. The Virgin and Christ are enthroned, surrounded by angels and saints, including St. Wolfgang and St. Benedict. The intricate architectural canopy above them further enhances the sense of celestial grandeur. The sheer depth of the carving and the animated quality of the figures create a powerful, almost theatrical effect.

The inner wings feature painted scenes from the Life of Christ: on the left, the Nativity, Adoration of the Magi, Presentation in the Temple, and the Flight into Egypt (though some scholars attribute the execution of some outer wing panels to his brother Friedrich Pacher or workshop assistants). On the right are scenes like the Raising of Lazarus, the Entry into Jerusalem, the Last Supper, and the Agony in the Garden. These paintings showcase Pacher's mastery of perspective, his ability to create convincing architectural settings, and his skill in narrative composition. The use of a low viewpoint in scenes like the Last Supper, for instance, clearly echoes Mantegna.

When the first set of wings is closed, four large painted panels depicting scenes from the Life of St. Wolfgang are visible. When fully closed, an outer set of wings (predella and superstructure also exist) would have displayed further scenes, often related to the liturgical calendar. The St. Wolfgang Altarpiece is considered one of the supreme achievements of late Gothic art in Europe, demonstrating Pacher's ability to manage a large-scale commission and to create a work of enduring spiritual and aesthetic power. Its influence on subsequent altarpiece production in the region was considerable.

The Altarpiece of the Church Fathers: Late Style and Innovation

Another significant work is the Altarpiece of the Church Fathers (Kirchenväteraltar), originally created for the Neustift Monastery (Novacella) near Brixen around 1483, now housed in the Alte Pinakothek in Munich. This work, from a later phase in his career, demonstrates a further refinement of his style and an even deeper engagement with Renaissance principles.

The four surviving panels depict the four great Latin Fathers of the Church: St. Jerome with his lion, St. Augustine with a child on the seashore, Pope St. Gregory the Great with Emperor Trajan appearing to him, and St. Ambrose with a child in a cradle. Each saint is rendered with remarkable individuality and psychological insight, set within meticulously constructed architectural interiors that showcase Pacher's command of perspective. The play of light and shadow is particularly sophisticated, creating a strong sense of volume and space.

In these panels, Pacher moves towards a greater sense of calm and monumentality compared to the more agitated drama of some earlier works. The figures possess a classical dignity, and the compositions are balanced and harmonious. The attention to detail, such as the books and writing implements in St. Jerome's study or the textures of the fabrics, is exquisite. This altarpiece exemplifies Pacher's mature style, where the fusion of Northern detail and Italianate spatial construction reaches a pinnacle of perfection. The influence of Netherlandish painters like Jan van Eyck (c. 1390–1441) or Rogier van der Weyden (c. 1399–1464) in terms of oil technique and detailed realism can also be felt, though filtered through Pacher's unique lens.

Other Notable Works and Attributions

Beyond these two major altarpieces, several other works are attributed to Pacher and his workshop. These include fragments of other altarpieces, individual panel paintings, and sculptures.

The "Devil Forcing St. Augustine to Write" (c. 1471-1475), also from the Neustift commission, shows a dynamic and almost humorous interaction, highlighting Pacher's narrative skill.

The "Marriage of the Virgin" and "Betrothal of the Virgin" panels (c. 1495-1498), now in the Österreichische Galerie Belvedere, Vienna, are from a late altarpiece for Salzburg and display a softer, more painterly style, perhaps indicating evolving artistic concerns or increased workshop participation in his final years.

Some works, like the "Rychnov Altarpiece," have been subjects of scholarly debate regarding their attribution to Pacher, reflecting the complexities of studying workshop production and the stylistic variations that can occur over an artist's career. The "Thomas Becket Altarpiece" in Graz is another example of a significant commission. His frescoes in the sacristy of Neustift, depicting scenes from the life of St. Sigismund, also show his command of wall painting, though they are not as well preserved.

Workshop, Collaborations, and Regional Impact

Michael Pacher operated a large and productive workshop, necessary for undertaking the monumental altarpiece commissions he received. His brother, Friedrich Pacher (active c. 1474–c. 1508), was also a painter and likely collaborated with Michael on several projects. While Michael was clearly the dominant artistic force, Friedrich's style, which was somewhat more traditional and less influenced by Italian innovations, can be distinguished in certain works or parts of larger commissions. Hans Pacher, possibly another relative, is also recorded as an artist active in the same period and region.

Pacher's influence extended throughout Tyrol, Salzburg, and parts of Bavaria. His innovative approach to perspective and his ability to imbue traditional religious subjects with new vitality set a standard for other artists in the region. He trained pupils, though specific names are not always securely documented, who would have disseminated his style. His impact can be seen as a bridge between the late Gothic world and the emerging Renaissance sensibilities in German-speaking lands, paving the way for later masters like Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), who himself traveled to Italy and grappled with similar artistic challenges of synthesizing Northern and Southern traditions, or Matthias Grünewald (c. 1470–1528), whose expressive intensity has Northern roots.

Later Years and Legacy

In the 1490s, Pacher moved his workshop to Salzburg, possibly due to larger commissions or a more favorable artistic environment. He was commissioned to create a high altarpiece for the Franciscan Church in Salzburg, a project he was working on at the time of his death. He died in Salzburg in the summer of 1498, before this altarpiece was fully completed.

Michael Pacher's death marked the end of a significant chapter in Central European art. His unique synthesis of Gothic emotionalism and Renaissance rationalism was a personal achievement that, while influential, was not directly replicated. The subsequent generation of artists in Germany and Austria would face the full force of the Italian High Renaissance and the Reformation, leading art in new directions.

Despite this, Pacher's major works, particularly the St. Wolfgang Altarpiece, have remained iconic. They are prized not only for their artistic merit but also as important cultural and historical documents. He is recognized as a transformative figure who, working from his Alpine workshop, engaged with the most advanced artistic ideas of his time and translated them into a powerful and enduring visual language. His ability to master both the chisel and the brush, creating unified works of art that spoke to both the intellect and the spirit, secures his place as one of the great masters of the late 15th century. His exploration of perspective and dramatic composition provided a crucial link for Northern artists seeking to understand and adapt the innovations of the Italian Renaissance.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision

Michael Pacher's art represents a fascinating confluence of cultural and artistic currents at a time of significant transition in European history. His journey, whether literal or intellectual, to the heart of the Italian Renaissance in Padua, and his subsequent reinterpretation of its principles within a deeply rooted Northern Gothic framework, resulted in works of extraordinary power and originality. From the intricate carvings of the St. Wolfgang Altarpiece to the contemplative dignity of the Church Fathers, Pacher's creations continue to captivate viewers with their technical virtuosity, emotional depth, and innovative spatial constructions. He remains a testament to the dynamic artistic exchanges that characterized the late medieval and early Renaissance periods, a Tyrolean master whose vision transcended regional boundaries to contribute significantly to the broader narrative of European art.