Neri di Bicci (1418/1419 – 1492) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the bustling artistic landscape of fifteenth-century Florence. While not always counted among the revolutionary innovators of the Early Renaissance, his prodigious output, the meticulous record-keeping of his workshop activities, and his role in disseminating prevailing artistic styles made him an indispensable part of the city's cultural fabric. His life and work offer a fascinating window into the day-to-day operations of a successful Renaissance workshop, the nature of patronage, and the artistic tastes of a broad clientele.

Early Life and Artistic Lineage

Born in Florence, likely in 1418 or 1419, Neri di Bicci was destined for a career in the arts. He was the third generation in a lineage of painters, a common phenomenon in Renaissance Italy where artistic skills and workshop practices were often passed down from father to son. His grandfather, Lorenzo di Bicci (c. 1350–1427), was a painter active in the late Gothic period, whose style reflected the prevailing International Gothic trends. Lorenzo's workshop was a known entity in Florence, undertaking various commissions.

Neri's father, Bicci di Lorenzo (1373–1452), continued the family tradition, adapting his style somewhat to the emerging currents of the Early Renaissance, though still retaining strong Gothic elements. Bicci di Lorenzo was a prolific artist in his own right, known for numerous altarpieces and frescoes. It was in his father's workshop, a vibrant hub of artistic production, that Neri di Bicci received his formative training. This apprenticeship would have involved grinding pigments, preparing panels, learning drawing techniques, and eventually assisting on commissions, gradually mastering the craft under his father's tutelage. This familial artistic environment provided Neri with a solid foundation in the technical aspects of painting and the business of running a workshop. In 1434, Neri formally joined the Florentine painters' guild, the Compagnia di San Luca (Guild of Saint Luke), a crucial step for any artist wishing to practice independently and accept commissions in the city.

The Workshop and Professional Career

Neri di Bicci's independent career effectively began after the death of his father, Bicci di Lorenzo, in 1452. He inherited the family workshop, which was already well-established, and continued its operations with remarkable efficiency and productivity for nearly four decades. The workshop became one of the most active in Florence, catering to a wide range of patrons, including prominent families, religious confraternities, parish churches, and convents, not only in Florence itself but also in surrounding towns and even further afield.

A unique and invaluable aspect of Neri di Bicci's career is his meticulous record book, known as Le Ricordanze. Maintained from 1453 to 1475, this diary is one of the most comprehensive surviving documents of its kind from the fifteenth century. It provides an unparalleled insight into the practicalities of a Renaissance painter's life and business. In Le Ricordanze, Neri detailed his commissions, the names of his patrons, the subjects of the artworks, the agreed prices, payment schedules, materials used, and even notes on his assistants and collaborators. This ledger reveals Neri not just as an artist but as a pragmatic businessman, managing a complex enterprise that involved negotiating contracts, sourcing materials, overseeing assistants, and ensuring timely delivery of finished works. The Ricordanze has been an essential source for art historians studying the economics of art production, patronage patterns, and workshop practices during the Quattrocento.

Artistic Style and Influences

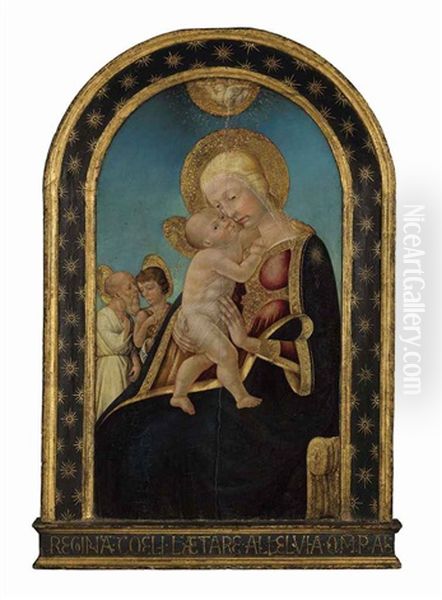

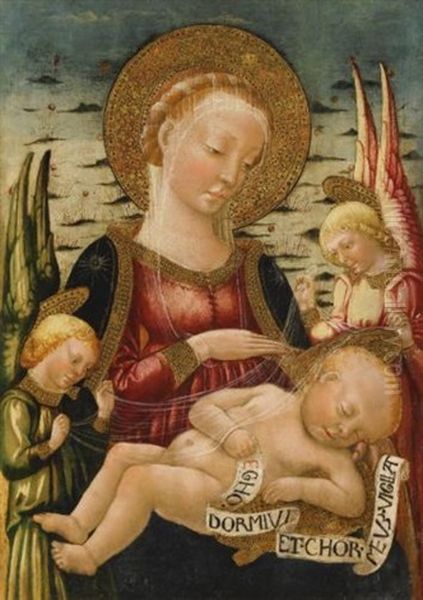

Neri di Bicci's artistic style is characteristic of the mid-Quattrocento in Florence, a period of transition and synthesis. He inherited a somewhat conservative, late Gothic sensibility from his father and grandfather, evident in his early works through a certain linearity, decorative patterning, and the use of traditional iconographies. However, Neri was not immune to the groundbreaking artistic developments happening around him. He gradually incorporated elements from the more progressive masters of the Early Renaissance.

His work shows an awareness of the innovations of artists like Fra Angelico (c. 1395–1455), particularly in the clarity of his figures, the gentle piety of his sacred personages, and the bright, luminous quality of his color palette. The influence of Filippo Lippi (c. 1406–1469) can be seen in the more human and tender portrayals of Madonnas and Child, and a certain sweetness of expression. There are also echoes of the narrative clarity and compositional organization found in the works of Domenico Ghirlandaio (1449–1494), though Ghirlandaio was a younger contemporary whose major works appeared later in Neri's career. Other artists whose stylistic traits Neri absorbed to varying degrees include Paolo Uccello (1397–1475) for his interest in perspective, albeit simplified in Neri's hands, and perhaps Andrea del Castagno (c. 1421–1457) for a certain sculptural quality in some figures. The decorative richness in his works, often featuring elaborate gold tooling and patterned textiles, also connects him to the tradition of painters like Gentile da Fabriano (c. 1370-1427), whose Adoration of the Magi was a landmark of International Gothic splendor in Florence.

Neri primarily worked in tempera on panel, the dominant medium for altarpieces and devotional paintings at the time. His compositions are generally well-ordered and legible, designed to clearly convey their religious narratives or devotional messages. While he may not have possessed the inventive genius of a Masaccio (1401–1428) or the intellectual depth of Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519), who was his contemporary in later life, Neri di Bicci developed a reliable and recognizable style that was highly sought after. His figures are often sturdy, with rounded faces and somewhat formulaic expressions, but they possess a directness and sincerity that appealed to his patrons. He was particularly adept at creating large-scale altarpieces with multiple saints, a format much in demand.

Major Works and Thematic Focus

Neri di Bicci's oeuvre is vast, consisting predominantly of religious subjects, which was typical for the period. He produced numerous altarpieces, devotional panels of the Madonna and Child, images of saints, and narrative scenes from the lives of Christ and the saints.

Among his notable works mentioned in the provided information and confirmed by art historical consensus:

_Coronation of the Virgin_ (1472): Originally for the monastery of San Pietro a Ruoti near Pisa, this work exemplifies his mature style. Such scenes were popular, depicting the Virgin Mary being crowned Queen of Heaven by Christ or God the Father, often surrounded by a host of angels and saints. Neri's versions are typically characterized by a symmetrical composition and a celestial ambiance, often with abundant use of gold.

_Saint Felicita and Her Seven Sons_ (1464): Located in the Church of Santa Felicita in Florence, this altarpiece demonstrates Neri's ability to handle multi-figured compositions. The subject, a Roman noblewoman martyred with her seven sons, was a powerful example of Christian faith and sacrifice.

_Annunciation_ (1464): Now housed in the Galleria dell'Accademia, Florence, this is a classic theme that Neri painted multiple times. His Annunciations typically follow traditional iconography, with the Archangel Gabriel appearing to the Virgin Mary, often set within an architectural space that shows a developing, if sometimes simplified, understanding of perspective.

_Madonna and Child Enthroned_ (e.g., the version in the Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena): This was one of the most frequently commissioned subjects. Neri produced many variations, often depicting the Virgin seated on an elaborate throne, holding the Christ Child, and flanked by saints or angels. These works served as focal points for private and public devotion.

_Tobias and Three Archangels_ (1471): This painting, now in the Detroit Institute of Arts, depicts a less common but popular subject in Florence, associated with safe journeys and divine protection. The inclusion of the three archangels (Raphael, Michael, and Gabriel) adds to its devotional power. Neri's treatment is characteristic of his clear narrative style.

_St. John Gualbert Enthroned with Ten Saints_ (c. 1455): Painted for the Vallombrosan Abbey of Santa Trinita in Florence, this large altarpiece shows the founder of the Vallombrosan Order, St. John Gualbert, enthroned and surrounded by other saints important to the order or the patrons. It showcases Neri's skill in organizing complex hierarchical compositions.

_The Martyrdom of St. Januarius_ (Uffizi Gallery, Florence): This panel depicts the martyrdom of an early Christian saint, a theme that allowed for dramatic representation, though Neri's approach tends to be more measured and less overtly emotional than some of his contemporaries.

_Saints Bartholomew and James Major_ (c. 1460-1470, Brooklyn Museum, New York): Likely part of a larger polyptych, such panels depicting individual saints were common components of complex altarpieces.

_The Virgin Listening to the Saints_ (Musée du Petit Palais, Avignon): This title suggests a sacra conversazione (holy conversation) format, where the Virgin and Child are depicted with a group of saints, seemingly in a shared spiritual space.

His works, while sometimes repetitive in their figural types, consistently display a high level of craftsmanship, vibrant color, and a clear understanding of the devotional needs of his patrons. He was a master of the workshop tradition, able to produce a large volume of work efficiently, often reusing cartoons and compositional formulas, a common practice that ensured consistency and speed.

Collaborations and Contemporaries

The Renaissance workshop was inherently a collaborative environment. Neri di Bicci, as head of a busy workshop, would have employed numerous assistants and apprentices over his long career. Le Ricordanze mentions some of them. For instance, a young Cosimo Rosselli (1439–1507) is recorded as an assistant in Neri's workshop from 1453 to 1456 before Rosselli went on to become a significant master in his own right, later working on the Sistine Chapel frescoes alongside Sandro Botticelli (c. 1445-1510), Domenico Ghirlandaio, and Perugino (c. 1446/1452-1523). Other assistants mentioned include Giusto d'Andrea and Bernardo di Stefano Rosselli.

These assistants would have been responsible for various tasks, from preparing panels and grinding colors to painting less critical parts of compositions, such as backgrounds, drapery, or predella scenes. This division of labor allowed the workshop to handle a large volume of commissions simultaneously.

Beyond direct employment, Neri di Bicci operated within a dense network of Florentine artists. He would have been aware of the works of slightly older or contemporary masters such as Benozzo Gozzoli (c. 1421–1497), known for his delightful narrative frescoes, or Alesso Baldovinetti (1425–1499), who experimented with oil techniques. The artistic scene in Florence was competitive but also collegial, with artists often belonging to the same guilds and confraternities, and influencing one another's styles. The towering figures of the earlier generation, like the sculptor Donatello (c. 1386–1466) and the architect Filippo Brunelleschi (1377–1446), had fundamentally reshaped the artistic landscape, and their impact was still felt during Neri's active years. He also worked alongside artists like Andrea del Verrocchio (c. 1435–1488), a painter and sculptor whose workshop trained Leonardo da Vinci.

Economic Realities and Workshop Management

The provided information touches upon financial difficulties, citing a lawsuit for debt in 1409 where property was lost. Given Neri di Bicci's birth year (c. 1418/19), this 1409 event almost certainly pertains to his grandfather, Lorenzo di Bicci, or his father, Bicci di Lorenzo, indicating that the family workshop may have faced financial pressures in earlier generations. Such economic fluctuations were not uncommon for artisan workshops.

Neri's own Ricordanze reveals that even a successful workshop head like himself experienced periods of financial strain. His records show instances of him pawning items between 1453 and 1475 to manage cash flow. This highlights the precarious nature of an artist's income, which was dependent on securing commissions and receiving timely payments. The costs of materials, workshop rent, and assistants' wages had to be carefully managed.

Despite these challenges, Neri's workshop was, by all accounts, a highly successful and profitable enterprise. His ability to produce a large quantity of good quality, if somewhat conventional, artworks made him a reliable choice for patrons. He was an astute businessman, as evidenced by the detailed financial records in his diary. He understood his market and catered to its demands effectively. The Ricordanze shows him undertaking a diverse range of commissions, from grand altarpieces for important churches to smaller devotional panels for private individuals, and even decorative work like painted banners or furniture. This diversification likely contributed to his workshop's long-term viability.

The Ricordanze: A Window into a Renaissance Workshop

The importance of Neri di Bicci's Le Ricordanze cannot be overstated for art historians. It is an exceptional document, offering a granular view of the inner workings of a fifteenth-century Florentine painter's studio. Few comparable records survive with such detail and over such an extended period.

The diary meticulously lists:

Commissions: The date of the commission, the patron's name and sometimes their profession or affiliation.

Subject Matter: A description of the work to be painted, often specifying the saints to be included or the narrative scene.

Dimensions and Materials: Details about the size of the panel, the use of gold leaf, specific pigments like ultramarine blue (which was very expensive).

Price and Payments: The agreed total price, and often a schedule of installment payments, which was common practice. This reveals the economic value placed on different types of artworks.

Assistants: Notes on which assistants worked on particular projects or their wages.

Other Expenses and Income: Records of buying materials, workshop rent, and even personal or household expenses and income from other sources, like property rental.

Delivery and Installation: Sometimes notes about the completion and delivery of the work, including costs for transport or installation.

Through Le Ricordanze, we learn about the types of patrons Neri served – from wealthy bankers and merchants like the Medici (though he was not one of their primary artists) to more modest parish priests and individual citizens. We see the collaborative nature of art production and the business acumen required to run a successful workshop. It also provides invaluable data for attributing works and understanding the chronology of Neri's output. The diary humanizes Neri, showing him not as an isolated genius but as a hardworking craftsman and entrepreneur deeply embedded in the social and economic life of his city.

Critical Reception and Legacy

In the grand narrative of art history, Neri di Bicci is often characterized as a conservative or traditional painter, particularly when compared to the great innovators of the Renaissance. Some critics have described his style as somewhat "archaic" or "mechanical," pointing to his repetition of figural types and compositions. While it is true that he was not a revolutionary artist who dramatically altered the course of painting, this assessment can overlook his considerable strengths and his importance within his specific context.

Neri di Bicci's success lay in his ability to consistently produce well-crafted, appealing, and devotionally effective artworks that met the demands of a broad market. His workshop was a model of efficiency, and his reliability made him a go-to artist for many patrons. He successfully synthesized prevailing artistic trends into a recognizable and popular style. His prolific output meant that his works were widely disseminated, helping to popularize certain iconographies and stylistic conventions throughout Tuscany and beyond.

His legacy is twofold. Firstly, there is his extensive body of artwork, hundreds of paintings that still adorn churches and are held in museum collections worldwide (including the Uffizi Gallery, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Louvre, and many others). These works continue to be studied for their iconographic content, their reflection of contemporary devotional practices, and their place within the broader Florentine school.

Secondly, and perhaps more uniquely, his legacy is cemented by Le Ricordanze. This document has provided generations of scholars with invaluable primary source material, making Neri di Bicci, paradoxically, one of the best-documented painters of his time, even if not the most famous. Through his meticulous records, we gain a richer understanding of the artistic profession in the Renaissance than is possible for many of his more celebrated contemporaries whose business affairs are less well-known.

Conclusion

Neri di Bicci died in Florence in 1492, the same year Columbus reached the Americas, a year often seen as a symbolic turning point in world history. He had lived through a period of extraordinary artistic ferment in Florence, witnessing the full flowering of the Early Renaissance and the emergence of figures who would define the High Renaissance, such as a young Michelangelo (1475-1564).

While Neri di Bicci may not have scaled the same artistic heights as some of his contemporaries, his contribution to the art of the Florentine Quattrocento was substantial and multifaceted. As a painter, he was a skilled and prolific master who satisfied the spiritual and aesthetic needs of a wide clientele. As a workshop head, he was an efficient manager and a trainer of other artists. And as a diarist, he left behind an invaluable record that continues to illuminate the world of the Renaissance artist. His career demonstrates that the art world relies not only on singular geniuses but also on the steady, diligent work of craftsmen who form the backbone of artistic production and cultural continuity. Neri di Bicci was, in this sense, an archetypal figure of the Renaissance workshop tradition, and his life and work remain a vital resource for understanding this pivotal era in Western art.