Bicci di Lorenzo (1373–1452) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the bustling artistic landscape of early Renaissance Florence. Born into an established family of painters, he inherited a thriving workshop and a conservative artistic tradition, which he skillfully navigated throughout a long and remarkably prolific career. While not an innovator on the scale of his more revolutionary contemporaries, Bicci di Lorenzo played a crucial role in satisfying the devotional and civic needs of a wide range of patrons, his work reflecting the gradual stylistic shifts from the entrenched International Gothic towards the burgeoning ideals of the Renaissance.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in Florence in 1373, Bicci di Lorenzo was destined for a career in the arts. His father, Lorenzo di Bicci (c. 1350–1427), was a respected painter who ran a successful workshop, and it was here that young Bicci received his initial training. This familial apprenticeship was typical of the era, ensuring the continuity of workshop practices and styles. Lorenzo di Bicci himself was a follower of the Orcagnesque tradition, a style derived from Andrea Orcagna and his brothers, which emphasized clear narrative and solid, somewhat archaic figural forms.

Beyond his father's direct tutelage, Bicci di Lorenzo's early artistic vocabulary was shaped by the dominant Florentine painters of the late 14th century. The enduring influence of Giotto di Bondone, the great progenitor of Florentine painting, was still palpable, particularly through the work of his followers. More immediately, Bicci's early works show an affinity with artists like Agnolo Gaddi, whose style was characterized by a lively narrative sense, decorative richness, and a certain adherence to late Gothic conventions. These influences provided Bicci with a solid foundation in traditional techniques, including fresco and tempera panel painting.

The Bicci Workshop and its Operations

Upon his father's death, Bicci di Lorenzo inherited the family workshop, which became one of the most active and productive in Florence during the first half of the 15th century. The workshop system was central to artistic production in this period. It was not just a place of creation but also a business, training ground, and collaborative enterprise. Bicci, like his father before him and his son Neri di Bicci after him, managed a team of assistants and apprentices who would help with various stages of a commission, from preparing panels and grinding pigments to painting less critical areas of a composition.

In 1424, Bicci di Lorenzo formally enrolled in the Arte dei Medici e Speziali, the Florentine guild to which painters belonged. He also became a member of the Compagnia di San Luca (Guild of Saint Luke), a confraternity of artists. These affiliations were important for securing commissions and establishing a professional standing within the city. The Bicci workshop was known for its reliability and its ability to produce a wide array of artworks, including large-scale fresco cycles, elaborate altarpieces, smaller devotional panels, and even painted marriage chests (cassoni).

Artistic Style: A Blend of Tradition and Innovation

Bicci di Lorenzo's artistic style is often characterized as transitional. He remained deeply rooted in the International Gothic style, which was popular across Europe in the late 14th and early 15th centuries. This style emphasized elegant, elongated figures, flowing drapery, rich colors, and often, lavish use of gold leaf for backgrounds and decorative details. Bicci's work consistently displays these characteristics, appealing to patrons who appreciated the decorative and narrative qualities of this established aesthetic.

However, living and working in Florence during a period of intense artistic ferment, Bicci could not remain entirely untouched by the new ideas that were beginning to reshape art. Figures like Filippo Brunelleschi, Donatello, and Masaccio were pioneering new approaches to perspective, human anatomy, and naturalism. While Bicci never fully embraced the revolutionary aspects of the early Renaissance in the way Masaccio did, his later works show a growing awareness of these developments. There is often a greater sense of volume in his figures, a more ordered spatial arrangement, and a softening of the purely linear Gothic rhythms. His style can be seen as a conservative but competent adaptation, absorbing certain Renaissance elements without abandoning the core of his traditional training. This made his work accessible and appealing to a broad clientele, including those less inclined towards the more austere intellectualism of the High Renaissance pioneers.

Major Commissions and Fresco Work

Bicci di Lorenzo was a prolific fresco painter, undertaking numerous large-scale commissions for churches and confraternities in Florence and surrounding Tuscan towns. Fresco painting, or painting on fresh plaster, was a demanding technique that required speed, skill, and careful planning.

One of his significant early commissions involved work in the Florence Cathedral, Santa Maria del Fiore. Around 1427-1430, he was commissioned to paint figures of the Apostles in terracotta, likely for the niches of the tribune, a project that also involved the sculptor Donatello in a supervisory or collaborative capacity for other elements. This indicates Bicci's standing as a trusted artist capable of contributing to the city's most important religious edifice.

He was also active in the decoration of the church of San Domenico in Cortona and later in Fiesole. A notable, though ultimately unfinished, commission was for the main chapel of the church of San Francesco in Arezzo. Around 1447, Bicci began a fresco cycle depicting the Legend of the True Cross for the Bacci family. However, due to failing health, he was unable to complete the project. This prestigious commission was eventually taken over and brought to iconic status by the great Umbrian master Piero della Francesca, whose frescoes in Arezzo are now considered one of the pinnacles of Renaissance art. Bicci's initial work on this cycle included scenes such as the Evangelists and parts of a Last Judgment.

Another important fresco is the Madonna della Cintola (Madonna of the Girdle), a theme particularly popular in Tuscany, depicting the Virgin Mary giving her girdle to Saint Thomas the Apostle at her Assumption. Bicci painted this subject for the church of the hospital of Santa Maria Nuova in Florence. He also executed a version of this theme as a fresco in the church of Santa Felicita in Florence. For the convent of Fuligno in Florence, he painted an Annunciation fresco, noted by some art historians for its particular iconographic details, such as the symbolic use of the bed in the Virgin's chamber.

Altarpieces and Panel Paintings

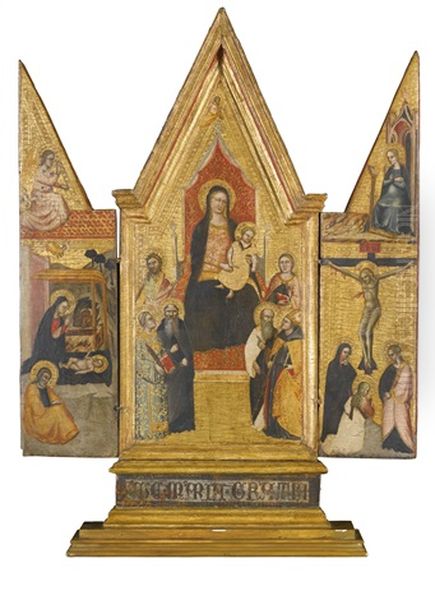

Alongside his fresco work, Bicci di Lorenzo produced a vast number of altarpieces and smaller devotional panels in tempera on wood. These works catered to the devotional needs of both ecclesiastical institutions and private patrons. His altarpieces often followed traditional formats, such as the triptych (a three-panelled work) or polyptych (multiple panels).

Among his representative altarpieces is an Annunciation with Committors and Saints, a theme he revisited multiple times. These works typically feature the Archangel Gabriel announcing the divine conception to the Virgin Mary, often flanked by patron saints or the donors who commissioned the work. The compositions are usually symmetrical, with rich colors and gold backgrounds enhancing their sacred character.

A notable Madonna and Child with Saints by Bicci di Lorenzo is now housed in Westminster Abbey, London. This panel, likely the central part of a larger polyptych, shows the Virgin enthroned with the Christ Child, surrounded by saints, a common subject that allowed for the inclusion of patrons' namesake saints or saints of particular local veneration. Another example of his panel painting is the Madonna and Child with St. Bartholomew and St. John the Evangelist, created for the church of San Bartolomeo in Siena, demonstrating his activity beyond Florence.

In 1447, Bicci di Lorenzo was involved in a significant commission in Siena, collaborating with the more progressive Venetian-born painter Domenico Veneziano on the main altarpiece for the church of Santa Maria della Scala. While Domenico Veneziano was the principal artist for this project, Bicci's participation underscores his reputation and ability to work on high-profile commissions even outside Florence.

Workshop Collaborations, Assistants, and Influence

Bicci di Lorenzo's workshop was a hub of activity, and collaboration was common. He is known to have worked with other artists on specific projects. For instance, records indicate a collaboration with Stefano di Antonio Vanni on an altarpiece. Stefano di Antonio was another Florentine painter active in the first half of the 15th century, and such joint ventures were not unusual, especially for large or complex commissions.

The workshop also served as a training ground. While direct master-pupil relationships are not always clearly documented, it is known that Giovanni di Ser Giovanni Guidi, known as Lo Scheggia, the younger brother of the revolutionary painter Masaccio, worked in Bicci di Lorenzo's workshop for a period. This connection is intriguing, as Scheggia himself became a prolific painter, particularly of cassoni and other decorative furnishings.

There has been speculation among art historians that Masaccio himself might have spent some time in Bicci's workshop during his formative years. Bicci's workshop was one of the largest and most established in Florence at the time Masaccio was beginning his career, and it would have offered a traditional, solid grounding in painting techniques. While there is no definitive proof of this, it remains a plausible hypothesis given the interconnectedness of the Florentine artistic community.

An interesting, though perhaps apocryphal or misunderstood, anecdote concerns a collaboration with the sculptor Donatello. Some sources mention Bicci working with Donatello on a terracotta sculpture of the Coronation of the Virgin, with the work initially attributed to Donatello but later identified as Bicci's. It is more probable that Bicci was involved in painting a sculptural group or its architectural framework, as was common practice, or that he collaborated with Donatello on projects that involved both sculpture and painting, such as the tomb of Cardinal Baldassare Cossa (Antipope John XXIII) in the Florence Baptistery, for which Donatello and Michelozzo created the sculpture, and Bicci was involved in some of the painted elements or models. Vasari also mentions Bicci providing models for the stained glass windows of the Duomo, a project that involved many leading artists, including Lorenzo Ghiberti and Paolo Uccello.

The Family Legacy: Neri di Bicci

The artistic lineage of the Bicci family did not end with Bicci di Lorenzo. His son, Neri di Bicci (1418–1492), was trained in the family workshop and eventually inherited it, continuing its prolific output well into the latter half of the 15th century. Neri's style largely followed that of his father, maintaining a conservative, late Gothic-influenced approach even as Renaissance innovations became more widespread.

Neri di Bicci is particularly well-known to art historians for his Ricordanze, a detailed workshop diary kept from 1453 to 1475. This invaluable document provides a wealth of information about the day-to-day operations of a 15th-century Florentine workshop, including commissions, patrons, payments, materials, and the roles of assistants. It offers a unique glimpse into the practical realities of art production during this period and sheds light on the kind of workshop environment in which Bicci di Lorenzo himself would have operated and which Neri perpetuated. The Bicci workshop, spanning three generations from Lorenzo di Bicci through Bicci di Lorenzo to Neri di Bicci, represents a remarkable continuity of artistic tradition and commercial success.

Later Years and Enduring Significance

In his later years, Bicci di Lorenzo's health began to decline, which, as mentioned, impacted his ability to complete some commissions, most notably the Arezzo frescoes. He passed away in Florence in 1452, leaving behind a vast body of work and a thriving workshop that would continue under his son.

Bicci di Lorenzo's art may not possess the groundbreaking innovation of contemporaries like Masaccio, Fra Angelico, or Paolo Uccello. He was not a pioneer of perspective or a profound explorer of human emotion in the new Renaissance vein. Instead, he was a master craftsman, a reliable and highly productive painter who skillfully met the demands of his patrons. His art provided comfort, instruction, and devotional focus for countless individuals and communities.

His significance lies in his role as a bridge between the established Gothic traditions and the emerging Renaissance style. He represented a more conservative, yet popular, artistic current that ran parallel to the more radical innovations. His workshop's output demonstrates the widespread taste for an art that was decorative, narrative, and imbued with a familiar religious sensibility. Artists like Bicci di Lorenzo were the backbone of artistic production, ensuring that churches, confraternities, and private homes were adorned with images that reflected and reinforced the cultural and spiritual values of their time. His influence, perpetuated through his son Neri and the numerous assistants who passed through his workshop, contributed to the rich and diverse tapestry of Florentine art in the 15th century. While often overshadowed by the giants of the Renaissance, Bicci di Lorenzo remains an important figure for understanding the full spectrum of artistic practice in this pivotal period of art history.