Ary Scheffer stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of 19th-century European art. A Dutch-born painter who found his fame in Paris, Scheffer navigated the fervent currents of Romanticism while often retaining a sense of classical restraint and polish. His work, deeply imbued with literary, religious, and historical themes, resonated profoundly with his contemporaries, capturing the sentimental and introspective mood of an era. Though his reputation fluctuated after his death, modern scholarship has increasingly recognized his unique contribution to the Romantic movement and his role as a chronicler of its sensibilities.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations

Born in Dordrecht, Netherlands, on February 10, 1795, Ary Scheffer (originally Arij Scheffer) was immersed in art from his earliest years. His father, Johann Baptist Scheffer, was a painter of some note, specializing in portraits and genre scenes, who had moved from Mannheim to the Netherlands. His mother, Cornelia Lamme, was also a talented artist, a painter of miniatures and a descendant of a family of artists. This familial environment undoubtedly nurtured Ary's burgeoning talent. His younger brother, Henry Scheffer, would also become a painter, further cementing the family's artistic legacy.

The early death of Johann Baptist Scheffer in 1809, when Ary was just fourteen, marked a turning point. Cornelia, a woman of strong character and artistic discernment, took charge of her sons' education. Recognizing Ary's prodigious abilities, she made the decisive move to Paris in 1811. This relocation was pivotal, placing the young artist at the very heart of European artistic innovation and academic tradition. In Paris, Ary Scheffer became a student of Pierre-Narcisse Guérin, a prominent Neoclassical painter whose studio also, for a time, included future Romantic giants like Eugène Delacroix and Théodore Géricault.

Under Guérin, Scheffer would have absorbed the principles of Neoclassicism: clarity of line, idealized forms, and a focus on historical and mythological subjects rendered with gravitas. However, the winds of change were blowing through the art world. The heroic and often stark rationalism of Neoclassicism was beginning to yield to the emotional intensity, individualism, and imaginative fervor of Romanticism. Scheffer, while retaining a certain classical discipline in his technique, was increasingly drawn to the expressive potential of this new movement.

The Ascent in Romantic Paris

Scheffer began exhibiting at the Paris Salon in 1812, initially with works that showed the influence of his Neoclassical training. However, his artistic voice soon began to align more closely with the burgeoning Romantic sensibilities. He was particularly drawn to subjects from literature, history, and religion that allowed for the exploration of profound human emotions – love, sorrow, piety, despair, and longing.

His studio, located in the Nouvelle Athènes district of Paris, became a significant gathering place for the artistic and intellectual elite of the time. This area was a hub for Romantic figures, and Scheffer's circle included writers, musicians, and fellow artists. He formed lasting friendships with figures such as the composer Frédéric Chopin and the writer George Sand. Indeed, the building that housed his studio is now the Musée de la Vie Romantique (Museum of Romantic Life), a testament to his central role in the cultural life of the period.

Scheffer's personal charm and intellectual acuity, combined with his artistic talent, made him a popular figure. He also became involved in the political sphere, aligning himself with liberal causes. He was a supporter of the Orléanist cause and developed a close relationship with the family of Louis-Philippe, Duke of Orléans, who would become King of the French after the July Revolution of 1830. Scheffer served as an art tutor to Louis-Philippe's children, further solidifying his position within influential circles.

Literary Inspirations: Goethe, Byron, and Dante

A hallmark of Ary Scheffer's oeuvre is his deep engagement with literature. He possessed a remarkable ability to translate the dramatic and emotional core of literary narratives into compelling visual terms. The great poets and writers of the Romantic era, as well as earlier masters, provided fertile ground for his imagination.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's "Faust" was a particularly rich source of inspiration for Scheffer. He painted numerous scenes from this epic drama, capturing its philosophical depth and emotional turmoil. Works such as Faust in His Study (or Faust Doubting), Margaret at the Spinning Wheel, Margaret at the Sabbath, and Margaret Leaving Church became immensely popular. These paintings often focused on moments of intense psychological introspection or spiritual crisis, rendered with a characteristic blend of sensitivity and precision. His depiction of Marguerite, in particular, resonated with audiences, embodying a Romantic ideal of innocence, piety, and tragic love.

Lord Byron, another titan of Romantic literature, also fueled Scheffer's artistic output. Byron's tales of exotic adventure, passionate love, and heroic struggle were perfectly suited to the Romantic temperament. Scheffer's paintings inspired by Byron, such as The Giaour (a subject also tackled by Delacroix, offering an interesting comparison in their approaches to Orientalist themes), captured the dramatic intensity and melancholic grandeur of the poet's narratives. These works often featured dramatic compositions and a focus on the expressive power of the human figure.

Dante Alighieri's "Divine Comedy" provided another enduring source of inspiration. Scheffer's most famous work, and arguably one of the defining images of 19th-century Romanticism, is Francesca da Rimini (1835, with later versions). This painting depicts the tragic lovers Paolo and Francesca, whom Dante encounters in the second circle of Hell, eternally swept along by a violent wind. Scheffer's composition is both elegant and deeply poignant, capturing the lovers' eternal embrace and their sorrowful fate. The ethereal quality of the figures, their pale forms contrasting with the shadowy abyss, creates a powerful sense of otherworldly tragedy. This work was widely acclaimed and reproduced, cementing Scheffer's reputation. Other Dantean subjects included Dante and Virgil Encountering the Shades of Paolo and Francesca da Rimini.

Religious Sentiment and Moral Allegory

Alongside his literary subjects, Scheffer frequently turned to religious themes. His approach to sacred art was often characterized by a gentle piety and a focus on the compassionate aspects of Christian narrative. These works were less about dogmatic assertion and more about evoking feelings of solace, devotion, and spiritual reflection.

One of his most celebrated religious paintings was Christus Consolator (Christ the Comforter, 1837). This large-scale work depicts Christ surrounded by figures representing various forms of human suffering and affliction, offering them comfort and redemption. The painting was praised for its tender sentiment and its universal message of hope. It appealed to a broad audience, transcending denominational divides, and was widely disseminated through engravings.

Other religious works, such as The Temptation of Christ and The Three Marys at the Tomb, further demonstrated his ability to convey spiritual narratives with a quiet emotional power. Scheffer's religious paintings often featured a soft, luminous palette and a focus on expressive gestures and facial expressions, aiming to touch the viewer's heart rather than overwhelm them with dramatic spectacle in the vein of some of his contemporaries like John Martin in England, known for his apocalyptic biblical scenes.

The Art of Portraiture

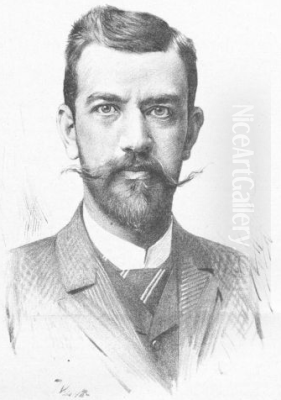

While Scheffer is perhaps best known for his literary and religious paintings, he was also a highly accomplished portraitist. His portraits are characterized by their psychological insight, refined execution, and an ability to capture the sitter's personality with sensitivity and elegance. He painted many of the leading figures of his day, including royalty, politicians, artists, and writers.

His close relationship with the Orléans family led to numerous commissions, including portraits of King Louis-Philippe, Queen Marie-Amélie, and their children. These royal portraits often combined formal dignity with a sense of intimacy, reflecting Scheffer's personal connection to the sitters. He also painted portraits of prominent figures such as the Marquis de Lafayette, the composer Franz Liszt, and the writer Alphonse de Lamartine.

His portraits of women are particularly noteworthy for their delicate rendering and empathetic portrayal. The portrait of his mother, Cornelia Scheffer-Lamme, is a tender and insightful depiction. His ability to convey not just a physical likeness but also an inner life made him a sought-after portrait painter throughout his career. This aspect of his work, while perhaps less dramatic than his narrative paintings, reveals his consistent technical skill and his keen observation of human character, a skill shared with masters like Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, though Scheffer's approach was often softer and more overtly sentimental.

Stylistic Characteristics and Critical Reception

Ary Scheffer's style is often described as a more restrained or "classical" form of Romanticism. While he embraced Romantic themes of emotion, individualism, and the sublime, his technique often retained a Neoclassical emphasis on clear drawing, smooth finish, and balanced composition. This sometimes led to criticism from those who favored the more overtly passionate and painterly style of artists like Delacroix. Some critics, both then and later, found his figures somewhat idealized or his emotionalism bordering on the sentimental. His color palette, particularly in his earlier works, could be subdued, leading to descriptions of his style as "frigidly classical" by some, though this term perhaps oversimplifies the nuanced emotional depth he often achieved.

Despite these criticisms, Scheffer enjoyed immense popularity during his lifetime. His paintings were widely exhibited at the Paris Salon and were eagerly sought after by collectors. Engravings and lithographs of his most famous works, such as Francesca da Rimini and Christus Consolator, circulated widely, bringing his art to a broad public across Europe and America. He was seen as an artist who could touch the heart and elevate the spirit, and his works were praised for their moral seriousness and refined sentiment.

The 1848 Revolution, which overthrew his patron Louis-Philippe, marked a shift in Scheffer's career and personal life. He became somewhat disillusioned with politics and increasingly focused on his art. In his later years, his style showed some evolution. There was perhaps a greater richness in his color and a continued exploration of profound human themes. He also experimented with Orientalist subjects, influenced by the broader European fascination with the East, though these were less central to his output than to artists like Jean-Léon Gérôme or Eugène Fromentin.

Contemporaries and Artistic Milieu

Ary Scheffer operated within a vibrant and competitive artistic environment in Paris. He was a contemporary of some of the greatest names in French art. Eugène Delacroix, the leading figure of French Romantic painting, was a near-exact contemporary. While both artists drew from literary sources and explored dramatic themes, their styles differed significantly. Delacroix's work was characterized by its dynamic compositions, rich color, and visible brushwork, conveying a sense of passion and energy. Scheffer, in contrast, generally favored a more polished finish and a more introspective emotional tone.

Théodore Géricault, another pioneer of Romanticism, whose Raft of the Medusa had stunned Paris, died relatively young in 1824, but his impact was profound. Scheffer would have been well aware of Géricault's powerful realism and dramatic intensity.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, a staunch defender of classicism and a master of line, represented a different artistic pole. While Scheffer shared with Ingres a concern for precise drawing and a smooth surface, his thematic concerns and emotional temperature were distinctly Romantic. The tension and dialogue between Neoclassicism and Romanticism defined much of the artistic discourse of the period, and Scheffer carved out his own space within this dynamic.

Other notable French painters of the era included Paul Delaroche, known for his historical melodramas, and Théodore Chassériau, who attempted a synthesis of Ingres's classicism with Delacroix's Romantic color. Scheffer's work can be seen in relation to these artists, all grappling with the representation of history, emotion, and the human condition in a rapidly changing world. Beyond France, the broader Romantic movement included figures like Caspar David Friedrich in Germany, with his sublime landscapes, J.M.W. Turner in Britain, with his atmospheric and proto-Impressionistic visions, and Francisco Goya in Spain, whose later works explored dark and unsettling psychological themes. Scheffer's more sentimental and literary Romanticism offered a distinct flavor within this international movement.

Legacy and Reassessment

Ary Scheffer died in Argenteuil, near Paris, on June 15, 1858. By the time of his death, new artistic movements, such as Realism, championed by Gustave Courbet, were beginning to challenge the dominance of Romanticism. In the latter half of the 19th century and into the 20th, Scheffer's reputation, like that of many academic and Romantic painters of his generation, declined as Impressionism and Modernism took center stage. His work was sometimes dismissed as overly sentimental or academic.

However, in more recent decades, there has been a significant reassessment of 19th-century art, and Scheffer's contributions have been re-evaluated. Art historians now recognize the sincerity of his artistic vision, his technical skill, and his importance as a representative of a particular strand of Romanticism – one that valued feeling, introspection, and moral uplift, often expressed through a refined and accessible visual language.

The Musée de la Vie Romantique in Paris, housed in his former studio, stands as a permanent tribute to his life and work, and to the Romantic era he so vividly embodied. His paintings are held in major museum collections around the world, including the Louvre in Paris, the Wallace Collection in London, and numerous museums in the Netherlands and the United States.

Ary Scheffer's art provides a window into the soul of the Romantic age. His engagement with literature, his sensitive portrayal of human emotion, and his ability to create images that resonated deeply with his contemporaries secure his place as an important artist of the 19th century. He may not have possessed the revolutionary fervor of Delacroix or the stark realism of Courbet, but his gentle, introspective Romanticism spoke to a profound human need for beauty, solace, and meaning, making his work enduringly relevant. His influence can be seen in the work of later Symbolist painters who also explored themes of introspection, dreams, and the spiritual, such as Gustave Moreau or Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, who, like Scheffer, often favored a more controlled and less overtly agitated style.

Conclusion: The Enduring Appeal of a Sentimental Romantic

Ary Scheffer's journey from a talented Dutch youth to a celebrated Parisian master is a story of dedication, artistic evolution, and a profound connection to the cultural currents of his time. He successfully navigated the transition from Neoclassicism to Romanticism, forging a distinctive style that combined technical polish with deep emotional resonance. His interpretations of literary masterpieces, his heartfelt religious scenes, and his insightful portraits captured the imagination of a generation and left an indelible mark on 19th-century art.

While tastes in art are ever-shifting, the power of Scheffer's work to evoke empathy and contemplation remains. He reminds us that Romanticism was not a monolithic movement but a diverse tapestry of artistic expressions. His particular thread – characterized by its sensitivity, its literary depth, and its often melancholic grace – continues to attract those who seek art that speaks to both the mind and the heart. In an art world often dominated by grand gestures and radical breaks, Ary Scheffer’s more subdued but deeply felt contributions offer a compelling vision of the Romantic spirit.