Introduction: The Dawn of a New Artistic Era

Ogata Gekkō stands as a pivotal figure in Japanese art, an artist whose career spanned the dynamic Meiji (1868–1912) and Taishō (1912–1926) periods. This era was characterized by Japan's rapid modernization and its complex engagement with Western culture, a transformation that profoundly impacted its artistic landscape. Gekkō, largely self-taught, navigated this changing world with remarkable skill, producing a diverse body of work that included ukiyo-e woodblock prints, paintings, book illustrations, and designs for ceramics and lacquerware. He successfully blended traditional Japanese aesthetics with new influences, creating a unique style that earned him both domestic and international acclaim. His art serves as a vibrant chronicle of his time, capturing everything from the beauty of nature and the elegance of women to the dramatic intensity of war and the enduring power of Japanese legends.

Early Life and the Forging of an Artist

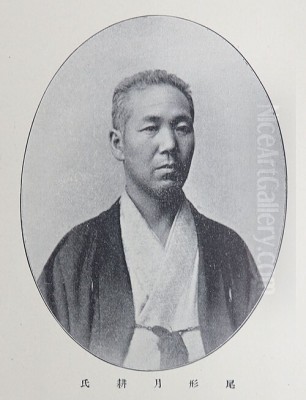

Born Nakagawa Masanari in 1859 in Kyōbashi Yazaemon-chō, Edo (present-day Tokyo), Gekkō's early life was marked by hardship. His father passed away when he was young, leading to the family's financial ruin. This adversity, however, seemed to fuel his determination. To make a living, the young Masanari turned to his innate artistic talents, initially decorating rickshaws and producing illustrations for popular consumption. This practical application of art for survival provided him with a foundational, albeit informal, training.

A significant turning point came at the age of sixteen when he was adopted by the Ōkura family. It was then that he adopted the name Ogata Gekkō, a name that would become synonymous with a distinct style of Meiji-era art. The choice of "Ogata" was likely an homage to the great Rinpa school master Ogata Kōrin , though Gekkō was not a direct descendant. This self-association with a revered artistic lineage signaled his ambition and his deep respect for Japanese artistic traditions, even as he forged his own path.

Unlike many of his contemporaries who trained under established masters in traditional schools like the Utagawa or Kanō schools, Gekkō was predominantly self-taught. He diligently studied various artistic forms, mastering the techniques of painting (Nihonga), woodblock print design, and illustration through his own efforts and observations. This independent spirit allowed him to develop a style that was less constrained by the rigid conventions of any single school, enabling him to experiment and synthesize diverse influences. While he is said to have briefly studied with the painter Kōsai Kikuchi , his artistic development was largely a testament to his personal drive and talent.

Artistic Style: A Synthesis of Influences

Ogata Gekkō's artistic style is characterized by its elegant fusion of traditional Japanese painting techniques and ukiyo-e sensibilities, subtly incorporating elements that show an awareness of Western artistic conventions. His work often displays a painterly quality, even in his woodblock prints, which set him apart from many ukiyo-e artists of the preceding Edo period.

A key influence on Gekkō was the Rinpa school, known for its decorative and often lavish style, its emphasis on nature, and its bold, patterned compositions. This can be seen in Gekkō's treatment of natural elements, his sophisticated color harmonies, and the overall elegance of his designs. He also drew from the Shijō school, which itself was a blend of the Kanō school's Chinese-influenced ink painting and the more naturalistic and decorative approach of Maruyama Ōkyo . This Shijō influence is evident in Gekkō's fluid brushwork and his sensitive depictions of flora and fauna.

Gekkō's prints are renowned for their delicate and sophisticated color palettes, often employing subtle gradations and soft hues that evoke a lyrical mood. His compositions are thoughtfully arranged, demonstrating a keen eye for balance and perspective. He was particularly adept at capturing the nuances of human expression and the ephemeral beauty of nature. His figures, especially women, are rendered with grace and sensitivity, often depicted in scenes of daily life, traditional customs, or historical narratives.

One of Gekkō's notable technical innovations, developed in collaboration with the carver Takeda Masahira, was the sashiage technique. This method involved applying color in a way that simulated the soft washes and blended tones of watercolor painting, giving his woodblock prints a unique, gentle texture and a greater sense of depth and atmosphere. This painterly approach was a hallmark of his work and contributed to his distinctiveness in the Meiji art world.

Themes and Major Works: A Diverse Repertoire

Ogata Gekkō's thematic range was exceptionally broad, reflecting the diverse interests of the Meiji populace and his own versatile talents. He explored traditional subjects with fresh perspectives and also documented contemporary events, creating a rich tapestry of Japanese life and culture.

Nature and Landscapes:

Nature was a recurring and beloved theme in Gekkō's art. He produced numerous prints and paintings depicting landscapes, flowers, and birds (kachō-ga). One of his most celebrated series in this vein is Gekkō Hyaku Fuji , showcasing Japan's iconic peak from various perspectives and in different seasons. These prints highlight his skill in capturing atmospheric effects and the sublime beauty of the natural world. His depictions often carry a poetic sensibility, reminiscent of traditional Japanese aesthetics that find profound meaning in nature.

Bijin-ga (Pictures of Beautiful Women):

Like many ukiyo-e artists, Gekkō excelled in bijin-ga. His portrayals of women are characterized by their elegance, grace, and often introspective mood. A notable series is Fujin Fūzoku Zukushi , which depicts women from different social classes engaged in various activities, offering insights into female life and traditional Japanese customs during the Meiji era. These works are admired for their delicate lines, refined colors, and sensitive portrayal of feminine beauty.

Historical and Legendary Subjects:

Gekkō frequently drew inspiration from Japanese history, literature, and folklore. He created several series based on classic tales, including illustrations for the Genji Monogatari . His series Gishi Shijūshichi Zu , depicting the famous story of the Akō vendetta, showcases his ability to convey drama and heroism. These works demonstrate his deep understanding of Japanese cultural heritage and his skill in narrative illustration. Another significant series is Gekkō Zuihitsu , a collection of prints covering a wide array of subjects, including historical scenes, legends, and everyday life, all rendered with his characteristic finesse. The Lonely House at Asajigahara is one such evocative print from this series.

War Prints (Sensō-e):

The Meiji era was a period of significant military engagement for Japan, and Gekkō became one of the leading artists documenting these conflicts. He produced a large number of sensō-e depicting scenes from the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895) and the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905). These prints, often triptychs, captured the drama and intensity of battles, naval engagements, and military life. While serving a journalistic and patriotic function, Gekkō's war prints are also notable for their artistic merit, demonstrating his compositional skills and his ability to convey action and emotion. Works like Fierce Battle at Ushigome (referring to a location, though specific titles varied widely, such as The Japanese First Army Advances Toward Mukden) exemplify his contributions to this genre. These prints were highly popular and played a role in shaping public perception of the wars.

The Sino-Japanese and Russo-Japanese Wars in Print

Ogata Gekkō's contributions to the genre of war prints (sensō-e) are particularly significant, positioning him as a leading visual chronicler of Japan's military conflicts during the Meiji era. The First Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895) and the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905) were pivotal events that asserted Japan's rising power on the international stage, and these conflicts generated immense public interest and patriotic fervor. Woodblock prints served as a primary medium for disseminating news and images of the wars to a wide audience, akin to modern photojournalism.

Gekkō, alongside artists like Kobayashi Kiyochika and Mizuno Toshikata , produced a prolific number of war prints. His depictions were known for their dynamic compositions, attention to detail, and often, a more humanized portrayal of soldiers compared to some of the more jingoistic works of the time. While undoubtedly patriotic, Gekkō's war prints often focused on the bravery, hardship, and strategic maneuvers of the Japanese forces. He created dramatic triptychs illustrating key battles, naval engagements, and scenes of military life, such as The Fall of Weihaiwei or The Great Naval Battle off the Coast of Haiyang Island.

His prints from the Russo-Japanese War continued this trend, capturing the scale and intensity of modern warfare. These works were not only popular domestically but also found an audience internationally, contributing to the global perception of Japan as a formidable military power. Gekkō's ability to combine reportage with artistic skill made his war prints highly effective. He managed to convey the chaos and heroism of battle while maintaining a level of artistic refinement, using his characteristic painterly style even in these dramatic and often violent scenes. The demand for these prints was immense, and artists like Gekkō worked rapidly to meet it, often relying on newspaper accounts and official reports for their information, as direct access to the front lines was limited.

Gekkō and the Art World of Meiji Japan

Ogata Gekkō was an active and respected member of the Meiji art world. Despite being largely self-taught, he gained recognition through participation in various exhibitions and art associations. He was a founding member of the Nihon Seinen Kaiga Kyōkai in 1891, an organization aimed at promoting new artistic endeavors. He also became a member and later a judge for the prestigious Nihon Bijutsu Kyōkai , which played a significant role in the official art scene of the time.

His involvement extended to other groups like the Ugōkai , which he formed with fellow Nihonga painters Suzuki Kason and Mishima Shōsō . He was also associated with the Kanga-kai , an art appreciation society. These affiliations demonstrate his engagement with his contemporaries and his commitment to the development of Japanese art.

Gekkō's contemporaries included a diverse array of artists who were shaping the Meiji art scene. Tsukioka Yoshitoshi was the last great master of traditional ukiyo-e, and Gekkō's career began as Yoshitoshi's was nearing its end. Kobayashi Kiyochika was known for his kōsenga (light-ray pictures) that incorporated Western perspective and light effects. Mizuno Toshikata , a student of Yoshitoshi, was a prominent bijin-ga and historical scene artist, and like Gekkō, also produced many war prints. Tsukioka Kōgyo , Yoshitoshi's adopted son, specialized in prints of Nō theatre.

Beyond the ukiyo-e tradition, the broader Nihonga movement was flourishing. Artists like Hashimoto Gahō , a leading figure of the Kanō school who also embraced new approaches, and his pupils Yokoyama Taikan and Shimomura Kanzan , were redefining Japanese painting. Takeuchi Seihō was another influential Nihonga painter who skillfully blended Shijō school traditions with Western realism. Watanabe Seitei , known for his exquisite kachō-ga, was one of the first Nihonga artists to study in Europe. The eccentric and powerful Kawanabe Kyōsai also left a significant mark with his dynamic and often satirical works. Kaburagi Kiyokata , though younger, emerged as a leading bijin-ga artist in the Nihonga style. Gekkō operated within this vibrant and evolving artistic milieu, carving out his own niche.

International Recognition and Versatility

Ogata Gekkō's talent did not go unnoticed beyond Japan's borders. As Japan increasingly participated in international expositions, Gekkō's works were frequently selected to represent the nation's artistic achievements. His prints and paintings were exhibited at several major world's fairs, where they garnered considerable acclaim and awards.

A significant moment of international recognition came at the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893. He continued to achieve success at subsequent international events. Notably, he won a gold medal for his series Gekkō Hyaku Fuji ("One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji by Gekkō") at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition (St. Louis World's Fair) in 1904. His work was also featured at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1900 and the Japan-British Exhibition in London in 1910, where he again received awards. This international exposure helped to introduce Japanese art, and Gekkō's unique style, to a Western audience, contributing to the Japonisme movement that was already influencing Western art. The art collector Matsukata Kōjirō , known for his vast collection of Western art that later formed the basis of Japan's National Museum of Western Art, was also a patron of Japanese artists, and figures like him played a role in promoting Japanese art both domestically and abroad.

Gekkō's artistic endeavors were not confined to prints and paintings. He was a remarkably versatile artist who also applied his skills to designing decorative arts. He created designs for lacquerware and ceramics, demonstrating his adaptability and his understanding of different artistic media. His book illustrations were also highly sought after, further broadening his reach and influence. This versatility was characteristic of some Meiji-era artists who sought to bridge the gap between "fine" and "applied" arts, a distinction that was less rigid in traditional Japanese art.

Legacy and Influence: A Bridge Between Eras

Ogata Gekkō passed away on October 1, 1920, at the age of 61, leaving behind a rich and diverse artistic legacy. His career successfully bridged the late ukiyo-e tradition of the Edo period and the emerging modern Japanese art movements of the Meiji and Taishō eras. While he was not a direct progenitor of the shin-hanga (new prints) or sōsaku-hanga (creative prints) movements that would flourish after his death, his painterly approach to printmaking and his emphasis on artistic expression prefigured some of the concerns of these later artists.

His influence can be seen in the way he maintained a high level of artistic quality while adapting to new themes and a changing market. He demonstrated that traditional techniques could be used to depict contemporary subjects, such as war, with both accuracy and artistry. His ability to blend Japanese aesthetic sensibilities with an awareness of Western art without sacrificing his cultural identity provided a model for other artists navigating the complexities of modernization.

Gekkō's dedication to his craft, his prolific output, and his success in both domestic and international arenas solidified his reputation as one of the foremost artists of his time. He trained several students, including Kōno Bairei who was more of a contemporary but with whom he shared an interest in bird-and-flower painting, and his adopted son Ogata Gessan , who continued his artistic lineage. However, his broader influence lay in his contribution to the visual culture of Meiji Japan and his role in showcasing Japanese art to the world.

Critical Reception and Market Performance

Academically, Ogata Gekkō is generally held in high regard as a significant artist of the Meiji period. Scholars recognize him as a key transitional figure who successfully navigated the shift from traditional ukiyo-e to more modern forms of Japanese printmaking and painting. His technical skill, particularly his innovative sashiage technique and his painterly style, is widely acknowledged. His ability to capture the nuances of Japanese life, culture, and history, as well as contemporary events, is praised. His works are seen as valuable historical documents as well as artistic achievements.

Some art historians have noted that while Gekkō embraced modern subjects and a somewhat modernized style, his work remained deeply rooted in traditional Japanese aesthetics and values. This is not necessarily a criticism but an observation of his position as a bridge between two worlds. There has been some discussion about whether his style leans more towards painting than traditional woodblock printing, which for some purists might seem a departure from ukiyo-e norms. However, this very quality is often what makes his work distinctive and appealing. His war prints, while popular and historically important, are sometimes viewed within the broader context of Meiji-era nationalism, though Gekkō's depictions are often considered more nuanced than those of some of his contemporaries.

In the art market, Ogata Gekkō's works continue to be popular among collectors of Japanese prints. Individual prints, particularly from his well-known series like Gekkō Zuihitsu or Fujin Fūzoku Zukushi, are regularly available through dealers and at auction. Prices for single sheets typically range from a hundred to several hundred U.S. dollars, depending on the subject, condition, rarity, and impression quality. More desirable or complete sets, such as his Hyaku Fuji, or particularly fine designs, can command higher prices. For instance, albums containing multiple works or exceptionally rare pieces can fetch significantly more; an album of Japanese woodblock prints including works by Gekkō was estimated at £8,000-£12,000 in a 2024 auction. His paintings, being unique works, generally command higher prices than his prints. His works are held in the collections of major museums worldwide, including the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; the British Museum, London; the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, attesting to his enduring artistic importance.

Conclusion: An Enduring Meiji Visionary

Ogata Gekkō was more than just a prolific artist; he was a keen observer and interpreter of a Japan undergoing profound transformation. His self-driven education and innovative spirit allowed him to create a unique artistic voice that resonated with both Japanese and international audiences. From the delicate beauty of a flower to the fierce dynamism of a battlefield, from ancient legends to contemporary customs, Gekkō captured the multifaceted spirit of Meiji Japan. His legacy endures in his vast body of work, which continues to be admired for its technical brilliance, aesthetic refinement, and its insightful portrayal of a pivotal era in Japanese history. As an artist who skillfully navigated the currents of tradition and modernity, Ogata Gekkō remains an important and fascinating figure in the rich tapestry of Japanese art.