Chobunsai Eishi stands as a unique and highly regarded figure in the vibrant world of Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock prints and paintings. Active during the late Edo period, specifically the Tenmei (1781–1789), Kansei (1789–1801), and Bunka (1804–1818) eras, Eishi carved a distinct niche for himself. Unlike many of his contemporaries who hailed from merchant or artisan backgrounds, Eishi was born into the samurai elite, a fact that profoundly shaped his artistic sensibilities and the refined elegance that characterizes his work. His journey from a high-ranking court official to a celebrated master of ukiyo-e is a fascinating tale of artistic passion triumphing over societal expectations, leaving behind a legacy of exquisitely beautiful depictions of women that continue to captivate audiences worldwide.

Early Life and Samurai Heritage

Born Hosoda Tokitomi in 1756, Eishi was a scion of a prestigious and wealthy samurai family, the Hosoda, who were direct retainers of the Tokugawa shogunate and claimed descent from the illustrious Fujiwara clan. His grandfather, Hosoda Tokitoshi , had held a significant position as a finance minister (Kanjo bugyo) for the shogunate. This privileged upbringing afforded Eishi a classical education and instilled in him the refined tastes and cultural understanding of the warrior aristocracy.

As a direct vassal to the Shogun, initially Tokugawa Ieharu and later Tokugawa Ienari , Eishi enjoyed a substantial hereditary stipend of 500 koku of rice annually (a koku being roughly 180 liters, enough to feed one person for a year). This financial security and social standing were considerable, placing him firmly within the upper echelons of Edo society. His early life was one steeped in the traditions and expectations of his class, which typically did not involve pursuing a career as a commercial artist.

Artistic Training in the Kano School

In keeping with his samurai status and the cultural pursuits deemed appropriate for his class, Eishi received formal training in painting. He studied under Kano Eisen'in Michinobu , a prominent painter of the Kano school who served as an official painter to the Shogun (oku-eshi). The Kano school was the dominant and most prestigious school of painting in Japan for centuries, patronized by the shogunate and the aristocracy. It was known for its strong brushwork, often Chinese-influenced subject matter (such as landscapes, birds and flowers, and Confucian sages), and its adherence to established classical forms.

Under Michinobu, Eishi would have mastered the traditional techniques and aesthetics of the Kano school. This rigorous training provided him with a strong foundation in draughtsmanship, composition, and the use of color, albeit within a very different stylistic framework from the ukiyo-e he would later embrace. His talent was recognized, and he eventually attained the position of a court painter, a role that involved creating works for the Shogun and his household. He even used the art name (gō) Eishi with the character "Ei" likely granted or inspired by his teacher Eisen'in.

The Pivotal Transition to Ukiyo-e

Around 1786 or 1787, when Eishi was in his early thirties, he made a life-altering decision. He resigned from his official position as a court painter to the Shogun. Sources suggest various contributing factors, including a period of illness, but a primary motivation appears to have been a burgeoning passion for ukiyo-e, the "pictures of the floating world." This was a radical departure for a man of his social standing. Ukiyo-e, while immensely popular, was considered a commercial, plebeian art form, catering to the tastes of the common townspeople (chōnin) and depicting the ephemeral pleasures of urban life – courtesans, kabuki actors, and famous landscapes.

By renouncing his official duties, Eishi effectively chose to become a "machi-eshi" (town painter), aligning himself with artists who often worked for publishers and a mass market. This transition was not without social consequence. It is said that his decision caused a stir and may have led to a cooling of relations with his former Kano school associates, who might have viewed his new path as a step down or even a betrayal of his classical training. Some accounts even suggest he was "expelled" or disavowed by the official art establishment for engaging in what they considered "vulgar art." Despite this, Eishi pursued his new calling with dedication, bringing his innate refinement and sophisticated aesthetic to the world of ukiyo-e.

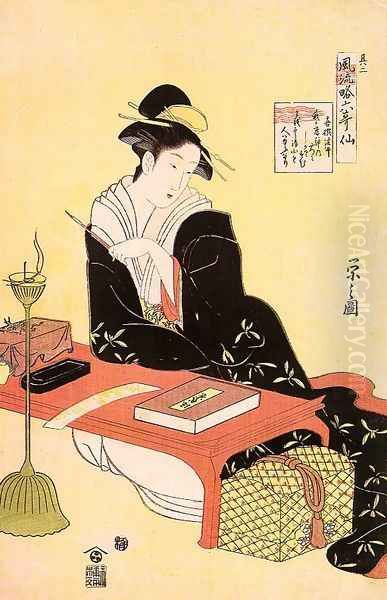

Eishi's Signature Style: Bijin-ga

Chobunsai Eishi is most celebrated for his bijin-ga (pictures of beautiful women). His depictions of women, whether courtesans of the Yoshiwara pleasure district, geishas, or ladies of leisure, are characterized by an extraordinary elegance, grace, and a sense of serene dignity. Unlike the more robust or overtly sensual portrayals by some of his contemporaries, Eishi's beauties are typically tall, slender, and willowy, with elongated figures and delicate features. Their faces often bear a calm, introspective, or slightly melancholic expression, conveying an air of quiet sophistication.

His compositions are meticulously balanced, and his use of color is subtle and harmonious, often employing soft pastels and rich, muted tones. Eishi paid great attention to the depiction of elaborate hairstyles and luxurious textiles, rendering the intricate patterns of kimono with remarkable precision. This refinement likely stemmed from his aristocratic background and Kano school training, which emphasized technical skill and a certain decorum. His figures possess a statuesque quality, often posed in gentle S-curves, which adds to their graceful allure. Even when depicting courtesans, Eishi imbued them with an aristocratic poise that set his work apart.

Themes and Subjects in Eishi's Work

While bijin-ga were his forte, Eishi's oeuvre encompassed a range of subjects. He produced numerous series illustrating classical Japanese literature, most notably The Tale of Genji (Genji Monogatari). These prints often depicted courtly scenes and characters from the famous novel, allowing him to blend his classical education with the ukiyo-e medium. His interpretations were imbued with a characteristic elegance and sensitivity to the emotional nuances of the Heian-period tale.

Another popular theme was the Rokkasen (Six Immortal Poets), where he would often create mitate-e (parody pictures or contemporary allusions) by portraying famous courtesans or contemporary beauties in the guise of these classical poets. Series such as Furyu Yatsushi Rokkasen (Fashionable Parodies of the Six Immortal Poets) were highly sought after.

Scenes from the Yoshiwara pleasure quarter were, of course, a staple. Eishi depicted famous courtesans, processions, and the daily life of the district, but always with his signature refinement, avoiding the more explicit or boisterous elements found in the work of some other artists. He also created sumo-e (pictures of sumo wrestlers) and occasionally musha-e (warrior prints), though these were less central to his output. Eishi was also a master of nikuhitsuga (original hand-painted works), which were highly prized and allowed for even greater subtlety and detail than woodblock prints.

Key Artistic Periods and Evolution

Eishi's artistic career in ukiyo-e can be broadly divided into two main phases. His early period, from the late 1780s through the 1790s, was primarily focused on woodblock print design. During this time, he produced many of his most famous print series. He excelled in various formats, including single sheets, diptychs, triptychs, and even larger multi-sheet compositions. He was particularly adept at creating harmonious group compositions, where multiple figures interact gracefully within a shared space. His early works show the influence of artists like Torii Kiyonaga, especially in the depiction of tall, elegant figures, but Eishi soon developed his own unmistakable style.

Around 1800 or 1801, Eishi largely ceased designing woodblock prints for commercial publication. He shifted his focus almost exclusively to nikuhitsuga – hand-painted scrolls and albums. This move may have been driven by a desire for greater artistic control, the higher prestige associated with painting, or perhaps a weariness with the collaborative and commercial aspects of print production. His paintings from this later period continued to feature his signature elegant beauties, often in more intimate settings or with more elaborate backgrounds, showcasing his refined brushwork and mastery of color. These paintings were commissioned by wealthy patrons and were considered luxury items.

Notable Works and Their Significance

Eishi's body of work is extensive and includes many masterpieces. Among his most celebrated print series are:

Seiro Bijin Awase (A Comparison of Beauties of the Green Houses, c. 1794-95): A renowned series depicting high-ranking courtesans from the Yoshiwara, showcasing their elaborate attire and dignified presence.

Furyu Yatsushi Rokkasen (Fashionable Parodies of the Six Immortal Poets, c. 1795-96): This series cleverly reimagined contemporary beauties as the classical poets, blending popular culture with literary tradition.

Genji Monogatari series: Eishi produced several series based on The Tale of Genji, such as Genji Jūni Kō (Genji in Twelve Months), demonstrating his literary knowledge and ability to translate complex narratives into visual form.

The Three Gods of Fortune Visit the Yoshiwara (c. 1795-1800, triptych): A famous work, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, depicting the gods Ebisu, Daikoku, and Fukurokuju enjoying the company of courtesans, a playful and auspicious theme.

Courtesans as Komachi (often referring to series like Furyu Nana Komachi - Seven Fashionable Komachis): These works depicted beauties in roles associated with the legendary poetess Ono no Komachi.

Individual prints like Standing Beauty Reading a Letter (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) exemplify his skill in capturing a moment of quiet introspection with grace and elegance. His kakemono-e (vertical diptychs designed to resemble hanging scrolls) and hashira-e (pillar prints) were also highly innovative and popular. His paintings, such as those depicting beauties by rivers or in garden settings, are prized for their delicate execution and serene atmosphere.

Eishi and His Contemporaries

Chobunsai Eishi was active during a golden age of ukiyo-e, and his work existed within a dynamic artistic environment populated by other brilliant talents. He was a direct contemporary and, in some ways, a rival to Kitagawa Utamaro (c. 1753–1806). While both specialized in bijin-ga, their approaches differed. Utamaro was known for his psychological insight and often more sensual, close-up portrayals of women, particularly their faces and upper bodies (okubi-e). Eishi, in contrast, generally favored full-length figures and an atmosphere of refined, almost aristocratic, detachment.

Eishi's style shows an acknowledged debt to Torii Kiyonaga (1752–1815), who, in the 1780s, established a popular mode of depicting tall, graceful beauties in group compositions. Eishi adopted and further refined this ideal of feminine beauty. He also would have been aware of the work of Katsukawa Shunsho (1726–1792), primarily known for actor prints but also a skilled painter of bijin-ga, whose studio produced many talented artists.

Other significant ukiyo-e artists active during parts of Eishi's career include:

Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849), whose immensely versatile and innovative work spanned landscapes, bijin-ga, and genre scenes, though his most famous landscapes came later.

Utagawa Toyokuni I (1769–1825), who became a dominant force in actor prints and also produced notable bijin-ga, founding the influential Utagawa school.

Kubo Shunman (1757–1820), a polymath known for his refined and subtle prints, often with poetic inscriptions, and a contemporary whose elegance sometimes paralleled Eishi's.

Hosoda Eiri (active c. 1780s–1800s), another artist with "Ei" in his name, sometimes confused with Eishi, but who developed his own distinct, elegant style of bijin-ga, often considered a friendly rival.

Kitao Shigemasa (1739–1820) and his pupil Kitao Masanobu (Santō Kyōden, 1761–1816), who were influential in bijin-ga in the period just before Eishi's rise.

Suzuki Harunobu (c. 1725–1770), though earlier, laid the groundwork for full-color prints (nishiki-e) and established an ideal of delicate, youthful female beauty that influenced subsequent generations.

Isoda Koryusai (1735–c. 1790), active as Eishi was beginning, known for his pillar prints and realistic depictions of courtesans.

Eishosai Choki (active c. 1780s–1800s), an artist whose works sometimes show stylistic similarities to Eishi's, particularly in the depiction of slender, graceful figures.

This rich artistic milieu provided both inspiration and competition, pushing artists like Eishi to continually refine their skills and develop unique styles.

Pupils and Legacy

Chobunsai Eishi was the founder of his own school of art, and he trained a number of pupils who carried on his elegant style. His most prominent students adopted art names beginning with "Ei" or "Cho" , in homage to their master. Among them were:

Chokosai Eisho : Perhaps his most faithful and talented pupil, Eisho produced bijin-ga that closely emulated Eishi's style, particularly his tall, slender figures and refined compositions. He is known for his depictions of courtesans from the Okamotoya house.

Ichirakutei Eisui : Known for his okubi-e (large-head portraits) of beauties, often with a slightly more robust quality than Eishi's typical figures, but still retaining an overall elegance.

Gessai Eishi : Not to be confused with Hosoda Eiri, this pupil also followed Eishi's style.

Chokyu Eiri

Eishin , also known as Tokusai Eishin.

Eishi's influence extended beyond his direct pupils. His refined aesthetic contributed to the overall elevation of bijin-ga as a genre. His works were highly prized in Japan and, like those of other ukiyo-e masters, eventually found their way to Europe and America in the late 19th century. There, they played a significant role in the Japonisme movement, influencing Impressionist and Post-Impressionist artists such as Edgar Degas, Mary Cassatt, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, who were captivated by the novel compositions, flattened perspectives, and decorative qualities of Japanese prints.

Eishi's Later Years and Shift to Painting

As mentioned, around 1801, Eishi largely withdrew from designing woodblock prints and dedicated himself to painting (nikuhitsuga). This shift marked a new phase in his career, allowing him to create unique, luxurious works for a discerning clientele. His paintings maintained the elegance and grace of his prints but often with even greater subtlety in brushwork and color. He continued to paint until late in his life.

His artistic achievements and his unique status as a samurai-artist were recognized. In 1800, one of his paintings was reportedly acquired for the collection of the retired Empress Go-Sakuramachi, a significant honor. After his death, he was posthumously granted the Buddhist honorary title (okurina) "Jibukyo Hoin Chobunsai Eishi Koji" , with "Jibukyo" being an honorary court rank. Chobunsai Eishi passed away on the first day of the seventh month of 1829 (August 1, 1829, by the Western calendar) and was buried at Rengeji Temple, later moved to Eiko-in Temple in Yanaka, Tokyo.

Critical Reception and Historical Standing

Chobunsai Eishi is consistently ranked among the great masters of ukiyo-e, particularly for his contribution to bijin-ga. His work is admired for its technical perfection, sophisticated compositions, and the serene, almost ethereal beauty of his female figures. He successfully bridged the gap between his aristocratic upbringing and the popular art form of ukiyo-e, infusing it with a distinctive elegance that reflected his own refined sensibilities.

His prints and paintings are held in major museum collections around the world, including the Tokyo National Museum, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the British Museum in London, and the Art Institute of Chicago, among many others. Exhibitions of his work continue to draw admiration for their timeless beauty and artistic skill. While perhaps not as widely known to the general public as Hokusai or Utamaro, Eishi is highly esteemed by connoisseurs and scholars of Japanese art for his unique style and significant contribution to the ukiyo-e tradition.

Conclusion

Chobunsai Eishi's life and art offer a compelling narrative of an individual who transcended the conventional boundaries of his social class to pursue his artistic vision. From the disciplined world of the samurai and the classical Kano school, he ventured into the vibrant, ephemeral "Floating World" of ukiyo-e, bringing with him an innate sense of grace and refinement. His depictions of beautiful women are not merely decorative; they are imbued with a quiet dignity and an idealized elegance that set them apart. Eishi's legacy is one of exquisite artistry, a testament to his mastery of line, color, and composition, and his enduring ability to capture a timeless vision of feminine beauty that continues to resonate with art lovers across cultures and centuries. He remains a pivotal figure in understanding the diversity and sophistication of ukiyo-e art during its golden age.