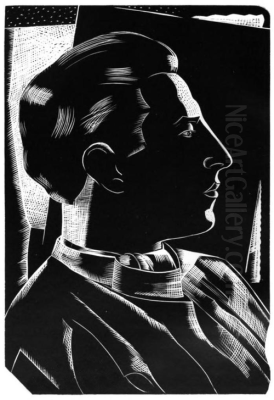

Paul Nash stands as one of the most significant figures in 20th-century British art. Born in London in 1889 and passing away in 1946, his career spanned a tumultuous period in history, marked by two world wars that profoundly shaped his artistic vision. Nash was a versatile talent – a painter primarily known for his landscapes and war scenes, but also a skilled photographer, writer, wood engraver, and designer of applied arts. His work uniquely blends a deep connection to the English landscape with the innovative currents of Modernism and Surrealism, leaving behind a legacy that continues to resonate.

From his early years spent in Buckinghamshire, Nash developed an intense fascination with the natural world, particularly the distinctive features of the English countryside. This love for landscape became the bedrock of his artistic practice. He pursued formal training at the Slade School of Fine Art in London, a prestigious institution where he honed his skills alongside contemporaries who would also make their mark, such as Stanley Spencer and Ben Nicholson. However, Nash himself admitted his strengths lay in landscape rather than figure drawing, a preference that would define much of his output.

Early Influences and Artistic Beginnings

In his formative years, Nash drew inspiration from the visionary Romanticism of artists like William Blake and Samuel Palmer. Their influence can be seen in his early works, which often possess a mystical, symbolic quality. He was captivated by particular places, seeking out what he termed the 'genius loci' – the spirit of place. This involved not just depicting the visual appearance of a landscape, but also evoking its history, atmosphere, and hidden character.

His early landscapes, often rendered in watercolour or wood engraving, display a lyrical quality. He was particularly drawn to specific natural forms, such as clumps of trees, ancient trackways, and coastal scenes. Works from this period began to establish his unique approach, combining careful observation with a poetic sensibility. He sought out landscapes imbued with a sense of timelessness or mystery, laying the groundwork for his later, more complex explorations of nature and human presence within it.

The Crucible of War: World War I

The outbreak of World War I irrevocably altered Nash's life and art. He enlisted in the Artists' Rifles before being commissioned into the Hampshire Regiment. In 1917, he was sent to the Western Front at the Ypres Salient. His initial letters home expressed a strange fascination with the landscape of war, but this soon turned to horror and disillusionment after experiencing the brutal realities of trench warfare. A non-combat injury led to his return to Britain later that year.

While recuperating, Nash worked from sketches made at the front, producing a series of powerful drawings and watercolours depicting the ravaged landscapes. These works caught the attention of the authorities, and he was recruited as an official war artist, returning to the front later in 1917. This second tour solidified his view of the war as an unforgivable violation of nature and humanity. He witnessed firsthand the obliteration of landscapes he loved, transforming fields and woods into nightmarish scenes of mud, shell craters, and shattered trees.

Nash's war art from this period is among the most iconic imagery produced during the conflict. He abandoned his earlier, more lyrical style for a harsher, more angular approach better suited to conveying the desolation he witnessed. His paintings capture the stark, geometric horror of the trenches and No Man's Land. He focused on the skeletal remains of trees, the churned earth, and the debris of battle, often under bleak, oppressive skies. Fellow war artists like C.R.W. Nevinson and Wyndham Lewis also depicted the conflict, but Nash's vision possessed a unique, haunting quality rooted in his profound connection to the violated landscape.

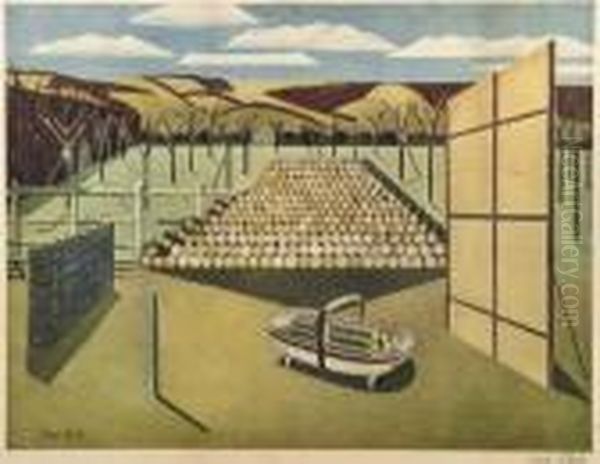

Key works such as The Menin Road (1919) exemplify his approach. The painting portrays a devastated landscape near Ypres, devoid of human figures but filled with water-filled shell holes reflecting a menacing sky, and jagged tree stumps standing like sentinels of death. It is a landscape utterly transformed by industrialised warfare, a powerful indictment of the conflict's destructive power. The work conveys a sense of profound loss and the seemingly insurmountable task of nature's recovery.

Another seminal work, We Are Making a New World (1918), presents a bitterly ironic title alongside a scene of a sun rising over a landscape brutalised by shellfire. The undulating mounds of earth resemble waves, while skeletal trees claw at the sky. The rising sun, traditionally a symbol of hope, here seems cold and indifferent, illuminating a scene of utter ruin. Nash used his art not merely to document, but to express his deep emotional response to the war – his anger, grief, and sense of outrage at the destruction.

Interwar Years: Exploration and Modernism

Returning from the war, Nash struggled to reconcile his experiences with peacetime life. His art continued to evolve, absorbing the lessons of the conflict while seeking new directions. He revisited familiar landscapes, but often imbued them with a lingering sense of unease or mystery, influenced by his wartime memories. His focus remained on the 'spirit of place', but now often tinged with melancholy or a surreal edge.

During the 1920s and 1930s, Nash became increasingly engaged with European Modernism. He travelled to France and was exposed to avant-garde movements, particularly Surrealism. The work of artists like Giorgio de Chirico, with its dreamlike spaces and enigmatic objects, resonated with Nash's own inclination towards the mysterious and symbolic. This influence began to filter into his work, leading to a greater degree of abstraction and unexpected juxtapositions.

He continued to explore specific locations that held personal significance, such as the coastline at Dymchurch in Kent and the ancient landscapes of Wiltshire and Dorset. Works like Dymchurch Steps (c. 1922-24) show a move towards simplified forms and a more structured composition, reflecting modernist sensibilities while retaining a strong sense of atmosphere. He became fascinated by prehistoric sites like Avebury and Stonehenge, seeing in their megalithic structures a connection to a deep, ancestral past embedded within the landscape.

Nash developed a keen interest in the 'found object' – natural forms like stones, pieces of wood, or fungi that seemed to possess an inherent character or life of their own. He would collect these objects and incorporate them into his paintings and photographs, often placing them in unexpected landscape settings. This practice aligned with Surrealist ideas about the uncanny and the hidden life of inanimate things. He believed these objects held a certain 'personality' or 'presence'.

His paintings from this era often feature these 'object-personages', as he sometimes called them. In works like Equivalents for the Megaliths (1935), abstract forms derived from found objects stand like monuments within a recognisable landscape, blurring the lines between the natural and the man-made, the ancient and the modern. He explored geometric patterns and abstract shapes, sometimes derived from natural forms, sometimes purely invented, creating compositions that were both formally rigorous and poetically evocative. Landscape at Iden (1929) uses geometric blocks and stark shadows to create a sense of quiet tension within a pastoral scene.

Unit One: Championing the Avant-Garde

By the early 1930s, Nash was a leading figure in the British art scene, keen to promote modern art in a country often perceived as resistant to continental innovations. In 1933, he spearheaded the formation of Unit One, a group intended to unite and showcase the best of British avant-garde talent across painting, sculpture, and architecture. The group aimed to represent what Nash called "the expression of a truly contemporary spirit."

Unit One brought together a diverse range of prominent artists. Its members included sculptors Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth, painters Ben Nicholson, Edward Wadsworth, Edward Burra, and Nash himself, along with architects Wells Coates and Colin Lucas, and the critic Herbert Read who acted as a spokesperson. The group represented the two main strands of British modernism at the time: abstraction (championed by Nicholson, Hepworth, Moore) and Surrealism (represented more by Nash and Burra).

Nash envisioned Unit One as a force to invigorate British art and design. The group held a major exhibition in London in 1934, which then toured the country. They also published a book, Unit One: The Modern Movement in English Architecture, Painting and Sculpture, edited by Herbert Read, featuring statements and works by each member. Nash's own contribution emphasized his interest in the mystical aspects of landscape and the 'life' of natural objects.

Despite its initial impact, Unit One was relatively short-lived. Internal tensions, particularly the differing artistic philosophies between the abstract and surrealist-leaning members, contributed to its dissolution by 1935. However, the group played a crucial role in raising the profile of modern art in Britain and fostering debate about its direction. It helped establish artists like Moore, Hepworth, and Nicholson as major international figures and solidified Nash's position as a key proponent of the avant-garde.

Surrealism and the Found Object

Nash's involvement with Unit One coincided with his deepening engagement with Surrealism. While he never fully subscribed to the psychoanalytic theories underpinning orthodox Surrealism as practiced in Paris by artists like André Breton or Salvador Dalí, he was drawn to its emphasis on dreams, the subconscious, and the uncanny. He participated prominently in the International Surrealist Exhibition held in London in 1936, a landmark event that introduced Surrealism to a wider British audience.

His interpretation of Surrealism remained rooted in his experience of the natural world. He used surrealist techniques – unexpected juxtapositions, dreamlike atmospheres, symbolic objects – to explore the hidden dimensions of landscape. He saw the potential for the ordinary to become extraordinary, for the familiar landscape to reveal surprising, sometimes unsettling, truths. His photographs from this period often focus on found objects arranged in evocative ways, or on strange natural formations.

The sculpture Moon Aviary (1937), a construction incorporating found wood and geometric shapes, exemplifies his surrealist object-making. Lost for many decades, its rediscovery highlighted this aspect of his practice. In paintings, he might place geometric forms floating inexplicably in the sky or anthropomorphise natural elements. He explored the idea of metamorphosis, where one form seems to transform into another, reflecting the constant flux he perceived in nature.

His fascination with ancient sites like the Wittenham Clumps in Oxfordshire, twin hills crowned with Iron Age forts that he painted repeatedly throughout his life, also fed into his surrealist leanings. He felt these places possessed a powerful, almost magical presence, connecting the contemporary landscape to a deep, mysterious past. His paintings of these sites often have a charged, expectant atmosphere, as if hinting at unseen forces or ancient rituals.

World War II: Return to War Art

With the outbreak of World War II, Nash once again offered his services as a war artist. He was appointed by the War Artists' Advisory Committee (WAAC), initially working with the Air Ministry and later the Ministry of Information. Now older and suffering from chronic asthma, which prevented him from undertaking strenuous frontline duties, his focus shifted. He became fascinated by the aerial dimension of the war – the conflict fought in the skies.

His WWII paintings often depict aircraft, both British and German, but rarely in straightforward documentary fashion. Instead, he treated planes almost as creatures inhabiting the sky, sometimes graceful, sometimes predatory. He was particularly struck by the wreckage of downed aircraft, seeing in their twisted metal forms a new kind of landscape, a 'dead sea' of debris.

This led to one of his most famous WWII paintings, Totes Meer (Dead Sea) (1940-41). Inspired by a dump of wrecked German aircraft he visited near Oxford, the painting transforms the metallic graveyard into a vast, undulating sea under a cold moonlit sky. The broken wings and fuselages resemble waves breaking on a shore, creating a powerful metaphor for defeat and the sterile destruction wrought by war. It is a landscape of death, yet rendered with a strange, haunting beauty.

Another major work, Battle of Britain (1941), depicts the aerial conflict over the English coast. It moves away from literal representation towards a more symbolic portrayal. Dogfights are shown as patterns of vapour trails and abstract shapes against vast cloudscapes, while the serene coastal landscape below seems both threatened and enduring. Nash captures the scale and drama of the air war, contrasting the human conflict with the timeless elements of sea and sky. Battle of Germany (1944) offers a more abstract vision of nocturnal bombing raids, portraying the burning city below as a hellish, glowing landscape seen from above.

Throughout his WWII work, Nash continued to blend observation with imagination, using landscape and symbolic imagery to convey the emotional and psychological impact of the conflict. His paintings from this period are less about the immediate horror of battle, as seen in his WWI work, and more about the broader themes of destruction, technology, and endurance.

Late Works and Legacy

In the final years of his life, despite declining health due to his severe asthma, Nash continued to paint prolifically. His late works often return to themes of landscape, season, and celestial events, imbued with a heightened sense of mysticism and symbolism. He produced a series of paintings inspired by the summer and winter solstices and the vernal and autumnal equinoxes, exploring the cyclical rhythms of nature.

His late landscapes, such as the Sunflower series, often feature powerful natural symbols like the sun and moon, depicted with vibrant colour and visionary intensity. These works, like Eclipse of the Sunflower (1945) and Solstice of the Sunflower (1945), seem to fuse his lifelong love of landscape with a deeper spiritual or metaphysical inquiry. They possess an ethereal, otherworldly quality, suggesting a final, transcendent vision.

Paul Nash died of heart failure in Boscombe, Hampshire, in July 1946, at the age of 57. He was buried in the churchyard at Langley Marish, Buckinghamshire. His unfinished autobiography, Outline, was published posthumously, offering valuable insights into his life and thought. His wife, Margaret Odey, whom he had married in 1914, played a supportive role throughout his career. His brother, John Nash, was also a notable painter, particularly of landscapes and botanical subjects, though their styles differed.

Paul Nash's legacy is multifaceted. He is remembered as one of Britain's greatest landscape painters, who revitalised the genre by infusing it with modernist sensibilities and a unique poetic vision. He was a pioneering war artist whose work powerfully conveyed the trauma of modern conflict. He was a key figure in the development of British Surrealism and a champion of the avant-garde through his involvement with Unit One. His influence extended beyond painting to encompass photography, illustration (such as his designs for Sir Thomas Browne's Urne Buriall and The Garden of Cyrus), and design.

His work continues to be celebrated for its unique blend of observation and imagination, its deep engagement with the spirit of place, and its profound reflection on the relationship between humanity, nature, and history. Artists like Graham Sutherland and John Piper acknowledged his influence, and his exploration of the British landscape paved the way for later generations of artists. Paul Nash remains a pivotal figure, whose art offers a compelling vision of a world undergoing radical transformation, seen through the lens of a deeply personal and poetic sensibility. His ability to find mystery in the familiar and meaning in destruction marks him as a truly original voice in modern art.