Introduction: An Umbrian Light in the Renaissance

Pietro di Cristoforo Vannucci, universally known by his nickname Perugino, stands as a pivotal figure in the Italian Renaissance. Active during the late 15th and early 16th centuries, he was a leading master of the Umbrian School of painting, celebrated for his serene compositions, harmonious figures, and luminous landscapes. His influence extended far beyond his native region, significantly shaping the High Renaissance style, most notably through his role as the teacher of the young Raphael. Perugino's art represents a bridge between the detailed linearity of the Early Renaissance and the balanced classicism that would define the subsequent era, leaving an indelible mark on the course of Western art.

Early Life and Florentine Formation

Born around 1446-1450 in Città della Pieve, a small town near Perugia in Umbria, Pietro Vannucci came from a family of some standing. His father, Cristoforo Vannucci, was a member of a respectable local family. While the art historian Giorgio Vasari later painted a picture of Perugino overcoming extreme poverty through sheer determination, modern scholarship suggests his background was likely more comfortable, allowing him access to education and artistic training from a young age. His nickname, "Perugino," simply meaning "the Perugian," became the name under which he achieved fame, linking him forever to the region that shaped his early sensibilities.

Crucial to Perugino's development was his move to Florence, the vibrant heart of the Early Renaissance, likely in the early 1470s. There, he entered the prestigious workshop of Andrea del Verrocchio, a master sculptor and painter whose studio was a crucible of artistic innovation. This environment provided Perugino with rigorous training in drawing, perspective, and composition. It also placed him alongside some of the most promising talents of his generation, including Leonardo da Vinci and Filippino Lippi, fostering an atmosphere of creative exchange and competition that undoubtedly spurred his growth.

The Emergence of a Distinctive Style

Perugino rapidly absorbed the lessons of Florence while retaining the gentle piety and spaciousness characteristic of Umbrian art. His style became a unique synthesis: the Florentine emphasis on clear drawing (`disegno`), anatomical accuracy, and rational perspective merged with the Umbrian preference for serene moods, delicate colour harmonies, and expansive, light-filled landscapes often dotted with feathery trees. He was influenced by the clarity and compositional structure seen in the works of Piero della Francesca, another towering figure with Umbrian connections, as well as the technical advancements of Flemish painters, particularly their mastery of the oil medium.

Perugino became one of the earliest Italian masters to fully embrace oil painting, appreciating its potential for subtle gradations of tone, rich colours, and luminous effects. His figures, often depicted with sweet, slightly melancholic expressions and clad in gracefully falling drapery, possess a quiet dignity. He excelled at creating balanced, symmetrical compositions, often employing linear perspective with skill to construct convincing architectural settings or deep landscape vistas. This combination of technical proficiency and gentle emotional appeal quickly brought him recognition and commissions.

The Sistine Chapel and Papal Patronage

Perugino's reputation reached Rome, leading to the most prestigious commission of his early career. In 1481, Pope Sixtus IV summoned him, along with other leading painters of the day including Sandro Botticelli, Domenico Ghirlandaio, and Cosimo Rosselli, to decorate the walls of the newly built Sistine Chapel in the Vatican. This collaborative project was a landmark of Renaissance art, intended to assert papal authority and magnificence through a complex theological program.

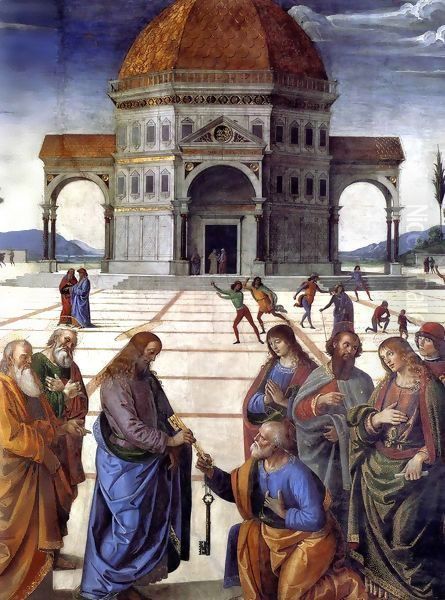

Perugino's contribution included several frescoes, the most famous and best-preserved being The Delivery of the Keys to Saint Peter. This masterpiece exemplifies his mature style. Set in a vast, geometrically paved piazza flanked by triumphal arches and a central octagonal building reminiscent of ideal Renaissance architecture, the scene depicts Christ bestowing the keys of heavenly authority upon a kneeling St. Peter. The figures are arranged in a frieze-like composition across the foreground, demonstrating clarity and order. The use of perspective is masterful, creating a profound sense of depth and rational space, embodying the Renaissance ideals promoted by theorists like Leon Battista Alberti. The calm solemnity of the figures and the harmonious integration of figures, architecture, and landscape made this work highly influential.

Flourishing Career and Workshop Practice

Following his success in Rome, Perugino's fame soared, making him one of the most sought-after artists in Italy. He established thriving workshops in both Florence and Perugia, managing a large number of assistants and pupils to meet the high demand for his work. His output was prolific, encompassing large altarpieces, devotional paintings for private patrons, frescoes for churches and public buildings, and portraits.

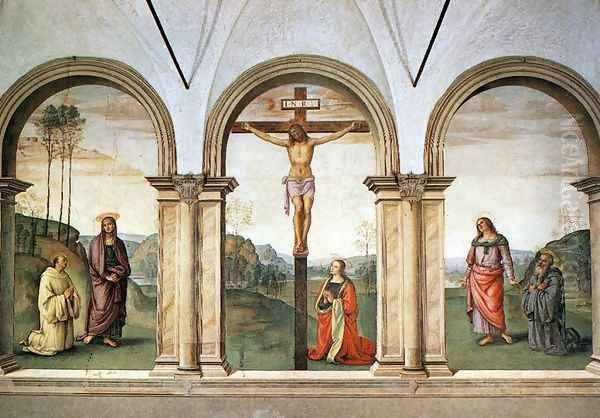

Among his many celebrated works from this period are numerous variations on the theme of the Madonna and Child, often accompanied by saints. Paintings like the Madonna and Child Enthroned with Saints John the Baptist and Sebastian (c. 1493, Uffizi, Florence) showcase his characteristic gentle figures, balanced composition, and serene landscape backgrounds. Other significant works include the Agony in the Garden (c. 1493-96, Uffizi), noted for its tranquil yet poignant atmosphere, and The Crucifixion with Saints (the Pazzi Crucifixion, c. 1494-96, Florence). His Lamentation over the Dead Christ (1495, Pitti Palace, Florence) demonstrates his ability to convey deep emotion through restrained gestures and expressions.

To maintain such a high level of production, Perugino's workshop relied on efficient practices. Drawings and cartoons (full-scale preparatory drawings) were often reused or adapted for multiple commissions. Assistants, trained in his style, would execute significant portions of paintings under his supervision. While this ensured consistency and allowed him to fulfill numerous contracts, it also contributed to a certain degree of standardization, particularly in his later works, which sometimes drew criticism for repetition. Collaborators and contemporaries in Umbria included the talented painter Pinturicchio, with whom Perugino sometimes worked and competed.

Leader of the Umbrian School

Perugino is rightly considered the preeminent master of the Umbrian School during the late 15th century. This regional school, while influenced by Florence, developed its own distinct character, favouring clarity, spaciousness, gentle sentiment, and a particular sensitivity to light and landscape. Perugino's work perfectly encapsulated these qualities. His paintings often feature wide, tranquil landscapes stretching into the distance under pale blue skies, populated by slender, graceful figures imbued with a quiet piety. This contrasted somewhat with the more dynamic, intellectually rigorous, and sometimes dramatic approach often favoured by Florentine contemporaries like Luca Signorelli (though Signorelli also had Umbrian roots and connections). Perugino's style became synonymous with Umbrian painting at its peak.

The Master of Raphael

Perhaps Perugino's most enduring legacy lies in his role as the teacher of Raffaello Sanzio, known to the world as Raphael. Around 1500, the young Raphael, already possessing formidable talent, entered Perugino's workshop, likely in Perugia. Vasari recounts that Raphael quickly mastered his teacher's style to such an extent that their works became almost indistinguishable. Raphael absorbed Perugino's techniques for creating balanced compositions, graceful figures, harmonious colours, and serene atmospheres.

Early works by Raphael, such as the Mond Crucifixion (c. 1502-03, National Gallery, London) and especially his Marriage of the Virgin (1504, Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan), clearly show Perugino's profound influence. Raphael's Marriage is directly comparable to Perugino's own version of the subject (c. 1500-04, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Caen). While Raphael adopts Perugino's compositional structure and figure types, his version already displays a greater sense of naturalism, dynamic movement, and spatial complexity, hinting at the independent genius that would soon blossom.

Although Raphael rapidly moved beyond his master's style after moving to Florence and encountering the work of Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Fra Bartolommeo, the foundational training he received from Perugino was crucial. Perugino provided him with the tools of composition and the sense of idealized grace that would remain hallmarks of Raphael's art throughout his meteoric career. Other followers and assistants influenced by Perugino included Lo Spagna (Giovanni di Pietro).

Later Years, Criticism, and Death

Perugino remained highly active throughout the early 16th century, maintaining his workshops and accepting major commissions, such as the frescoes for the Collegio del Cambio (the Audience Hall of the Moneychangers' Guild) in Perugia (1497-1500). These frescoes, depicting allegorical and religious scenes, are considered among his finest later works, showcasing his decorative skill and mastery of complex programs.

However, as the artistic climate shifted with the emergence of the High Renaissance giants Leonardo, Michelangelo, and his own former pupil Raphael, Perugino's style began to seem somewhat conservative to some critics. While still popular with many patrons, particularly in Umbria, his adherence to established formulas and the perceived sweetness or sentimentality of his figures drew criticism. Vasari, while acknowledging Perugino's earlier importance, characterized his later work as repetitive and motivated more by financial gain than artistic innovation, a judgment that has coloured his reputation to some extent.

Despite this, Perugino continued to work diligently. He spent his final years primarily between Perugia and Florence. In 1523, while working on a fresco in Fontignano, a town near Perugia, Pietro Vannucci Perugino died, likely a victim of the plague that swept through the area. He was buried hastily nearby, but his remains were later thought to have been transferred, possibly to the Church of the Santissima Annunziata in Florence, a city central to his artistic journey. His death occurred at the approximate age of 78, marking the end of a long and remarkably productive career.

Art Historical Significance and Legacy

Pietro Perugino occupies a significant place in the narrative of Italian Renaissance art. He was a master technician, among the first in central Italy to fully exploit the potential of oil paint. His command of perspective and his ability to create harmonious, balanced compositions set a standard for his time. He perfected a style characterized by serene beauty, gentle piety, and spatial clarity that resonated deeply with the religious and aesthetic sensibilities of the late 15th century.

His role as a leader of the Umbrian School cemented a regional artistic identity known for its grace and luminosity. His influence was widespread, disseminated through his numerous works and the activity of his large workshop. Critically, his tutelage of Raphael provided the younger artist with an essential foundation, making Perugino an indispensable link in the development of the High Renaissance.

While later criticism sometimes focused on the perceived limitations or repetitiveness of his style, particularly when compared to the revolutionary achievements of the subsequent generation, Perugino's contribution remains undeniable. He was a master craftsman, an influential teacher, and the creator of works of enduring calm and beauty. His paintings continue to be admired for their technical skill, harmonious design, and the tranquil, idealized world they depict. The commemoration of the 500th anniversary of his death in 2023 with exhibitions and studies reaffirms his lasting importance in the history of art.

Conclusion

Pietro Vannucci, "Il Perugino," was more than just a precursor to the High Renaissance; he was a defining artist of his own era. His synthesis of Umbrian serenity and Florentine structure, his mastery of composition and light, and his prolific output secured his fame across Italy. Though sometimes overshadowed by his most famous pupil, Perugino's own artistic achievements and his crucial role in shaping the course of Renaissance painting ensure his enduring significance as a master whose gentle vision continues to captivate viewers centuries later.