Franz Anton Maulbertsch stands as one of the most significant and distinctive painters of the late Baroque period in Central Europe. Active during the latter half of the 18th century, this Austrian master left an indelible mark primarily through his breathtaking fresco cycles, which adorn numerous churches and palaces across Austria, Hungary, the Czech Republic (Bohemia and Moravia), and Slovakia. His work is characterized by vibrant, often daring color palettes, dynamic compositions, profound emotional intensity, and a unique synthesis of Italian influences and a deeply personal, expressive style. Though sometimes overlooked in broader surveys of European art, Maulbertsch's genius lies in his ability to convey complex theological and allegorical narratives with unparalleled visual drama and spiritual depth.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Vienna

Franz Anton Maulbertsch was born on June 7, 1724, in Langenargen on Lake Constance, a region then part of Further Austria. His father, Anton Maulbertsch, was also a painter, likely providing his son's initial artistic instruction. Seeking greater opportunities, the young Maulbertsch moved to Vienna, the vibrant capital of the Habsburg Empire and a major center for the arts. He enrolled in the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts (Akademie der bildenden Künste Wien) in 1739, a crucial step in his development.

During his formative years at the Academy, Maulbertsch absorbed the prevailing artistic currents. The Viennese art scene was heavily influenced by Italian Baroque traditions, particularly the Venetian school. He studied under Jacob van Schuppen, the Academy's director, but more significant influences came from exposure to the works of earlier and contemporary masters. Paul Troger, another prominent Austrian painter known for his dramatic frescoes, was a significant figure at the Academy and his dynamic style likely impacted the young Maulbertsch.

The curriculum and artistic environment in Vienna exposed Maulbertsch to a rich tapestry of styles. He diligently studied the works of Venetian painters whose influence was palpable in the city. Key among these were Giovanni Battista Piazzetta and Giovanni Battista Pittoni. Their emphasis on rich color (colorito), expressive brushwork, and dramatic light effects resonated deeply with Maulbertsch's emerging sensibilities. He learned from their handling of religious and mythological themes, absorbing techniques that would become foundational to his own practice.

The Enduring Influence of Venetian Masters

Beyond the direct tuition at the Academy, Maulbertsch actively studied the works of Venetian masters who had worked in Vienna or whose paintings were accessible in collections. The frescoes painted by Sebastiano Ricci in the Schönborn Palace provided a powerful example of large-scale decorative painting in the Venetian High Baroque manner. Ricci's fluid brushwork, luminous colors, and elegant compositions offered a compelling model for monumental ceiling decorations.

Perhaps the most significant Venetian influence, particularly regarding scale, light, and theatricality, came from Giambattista Tiepolo. Although Tiepolo worked primarily in Würzburg and later Madrid during Maulbertsch's main period of activity, his reputation and style were pervasive. Maulbertsch studied Tiepolo's approach to vast, light-filled celestial visions, his mastery of perspective (especially sotto in sù, or "seen from below"), and his ability to orchestrate complex multi-figure compositions across enormous surfaces. While Maulbertsch developed a distinct personal style, the ambition and technical brilliance of Tiepolo remained a touchstone. He adapted the Venetian emphasis on color and light but infused it with a unique Central European intensity and emotional fervor.

Development of a Unique Artistic Style

Emerging from his training, Maulbertsch rapidly developed a highly individual style that set him apart from many of his contemporaries. His work is often characterized by an almost ecstatic energy, conveyed through swirling compositions, dynamic figure poses, and, most notably, his extraordinary use of color and light. He employed a palette that could range from delicate pastel shades, typical of the Rococo, to intense, almost dissonant combinations of vibrant hues – cool blues and pinks juxtaposed with fiery oranges, reds, and yellows.

His handling of light was equally distinctive. He mastered dramatic chiaroscuro, using strong contrasts between light and shadow to model forms, create spatial depth, and heighten the emotional impact of his scenes. Figures often emerge from deep shadow into brilliant, sometimes supernatural light, emphasizing moments of divine revelation or intense human feeling. This dramatic illumination contributed significantly to the theatrical quality of his large-scale frescoes.

Maulbertsch's brushwork was typically fluid and energetic, prioritizing expressive effect over meticulous finish, particularly in his oil sketches (bozzetti) and frescoes. While some contemporary critics occasionally noted perceived flaws in drawing or an occasional awkwardness in drapery, these aspects are often reinterpreted today as part of his expressive intensity, sacrificing academic precision for emotional power. His style represents a unique fusion of the elegance and lightness of Rococo with the dramatic power and spiritual depth of the late Baroque, filtered through his own passionate artistic temperament.

Master of the Fresco: Monumental Commissions Across Central Europe

Maulbertsch's reputation rests primarily on his prolific output as a fresco painter. From the 1750s onwards, he received numerous commissions to decorate the interiors of churches, monasteries, and palaces throughout the Habsburg lands. These monumental projects allowed him to fully deploy his talents for large-scale composition, dramatic narrative, and vibrant color.

One of his earliest major independent commissions was the ceiling fresco for the Piarist Church of Maria Treu in Vienna (1752-1753). This work, depicting the Miracles of the Holy Sacrament and the Assumption of the Virgin, immediately established his reputation. It showcases his burgeoning mastery of complex aerial perspectives and his characteristic use of luminous, swirling color to depict heavenly glories. The dynamic energy and emotional intensity of the figures marked a significant departure from the more restrained styles of some older Viennese masters.

His renown quickly spread beyond Vienna. He undertook significant projects in Hungary, notably the extensive fresco cycle in the parish church (now cathedral) of Sümeg (1757-1758). Here, he covered vast areas of the ceiling and walls with scenes from the Old and New Testaments, demonstrating his ability to manage complex iconographic programs and maintain visual coherence across large architectural spaces. The Sümeg frescoes are celebrated for their narrative clarity and vibrant execution. Another key Hungarian commission was for the Cathedral of Győr.

In Moravia (now part of the Czech Republic), Maulbertsch executed important works, including the frescoes for the library of the Premonstratensian Monastery in Louka (Klosterbruck) near Znojmo (1766) and the ceiling frescoes in the Church of St. John the Baptist in Kroměříž. Perhaps his most famous work in the Czech lands is the decoration of the Philosophical Hall ceiling at the Strahov Monastery Library in Prague (1794). This late work, depicting the "Intellectual Progress of Mankind," shows a shift towards clearer, more classically influenced compositions, reflecting the changing artistic tastes of the era, yet it retains his characteristic dynamism and rich color.

He also worked extensively in Austria itself, outside of Vienna. Notable commissions include frescoes in the pilgrimage church of Heiligenkreuz-Gutenbrunn in Lower Austria and significant contributions to the decoration of the Hofburg palace in Innsbruck (1775-1776), where he painted the ceiling of the Giant Hall (Riesensaal) with scenes glorifying the Habsburg dynasty. He also decorated the parish church in Schwechat and contributed frescoes to the Michaelerkirche in Vienna, showcasing his continued prominence in the imperial capital. These vast projects often involved complex theological or allegorical programs devised in consultation with patrons, typically powerful church officials or members of the aristocracy.

Works in Other Media: Oil Paintings and Prints

While best known for his frescoes, Maulbertsch was also a highly accomplished painter in oils and a skilled printmaker. His oil paintings often served as preparatory studies (bozzetti) for his large-scale fresco projects. These sketches, typically executed with rapid, energetic brushwork, are highly prized today for their spontaneity and for revealing the artist's creative process. They capture the initial burst of inspiration and often possess an immediacy sometimes moderated in the final, larger works.

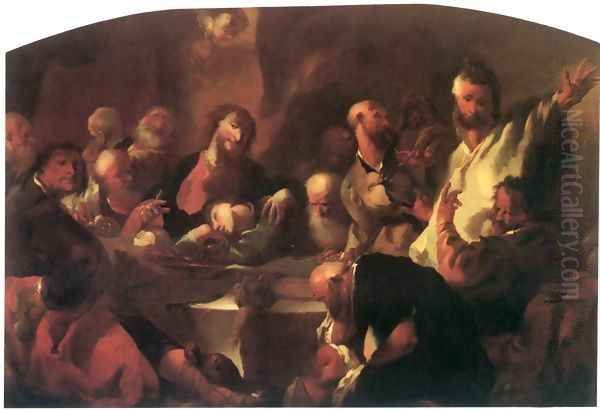

He also produced finished oil paintings, often for altarpieces or private devotional use. Works like The Assumption of the Virgin (examples exist in various collections, including the Harvard Art Museums) demonstrate his ability to translate the dynamism and colorism of his frescoes into the oil medium. Figures are often depicted with intense emotion, caught in moments of spiritual ecstasy or dramatic tension. The Blinding of Samson, another powerful example, showcases his flair for depicting dramatic biblical narratives, utilizing strong chiaroscuro and expressive figures to convey the violence and pathos of the scene.

Maulbertsch also engaged with printmaking, primarily etching. His most famous print is the complex allegorical work known as the Image of Toleration (or Allegory of Religious Tolerance), created around 1785. Published by the Viennese art dealer Franz Valerius Stokler, this etching reflects the spirit of Josephinism and the Enlightenment ideals promoted under Emperor Joseph II. It depicts a complex scene advocating for religious tolerance, featuring figures representing different faiths and philosophical concepts. This work demonstrates Maulbertsch's engagement with the intellectual currents of his time and his ability to translate abstract ideas into compelling visual form. He also produced portraits, such as the mentioned Portrait of Nasir of Jerusalem, although portraiture was not his primary focus.

Collaborations, Workshop, and Influence

Executing vast fresco cycles required significant assistance. Like most successful painters of his era, Maulbertsch maintained an active workshop with pupils and collaborators who helped transfer his designs onto the walls and execute less critical passages. This collaborative practice was standard for large-scale commissions.

Among his collaborators, Andreas Brugger worked with him on certain projects, such as the altarpiece for the church in Podivín (Kostel) in Moravia. More significant was his relationship with Joseph Winterhalder the Younger. Winterhalder was not only a student but also a close follower and collaborator who absorbed Maulbertsch's style effectively. After Maulbertsch's death, Winterhalder was sometimes entrusted with completing projects initiated by his master, attesting to his skill and stylistic affinity. The precise nature of his interaction with other contemporaries, like Eustachius Gabriel, remains less clearly documented but points to his integration within the broader artistic network of the region.

Maulbertsch's influence extended through his students and followers, who helped disseminate his style, particularly in fresco painting, across Central Europe. His dynamic compositions and vibrant colorism offered a powerful alternative to the increasingly dominant Neoclassicism in the later 18th century, although his own late work sometimes showed a slight accommodation to the newer style's clarity. His impact can be seen in the work of numerous church decorators active in Austria, Hungary, and the Czech lands during his lifetime and immediately after.

Later Career, Recognition, and Death

Maulbertsch remained highly active throughout his career, adapting to changing patronage needs and artistic trends while largely retaining his distinctive expressive style. He was appointed court painter by the Habsburgs and held prestigious positions at the Vienna Academy, including professor and later director of the council, reflecting the official recognition he achieved during his lifetime. His late works, like the Strahov Library ceiling, demonstrate his enduring creative power even as artistic fashions began to shift towards Neoclassicism.

Despite his contemporary success and prolific output, Maulbertsch's reputation experienced a period of relative decline after his death on August 7, 1796, in Vienna. The rise of Neoclassicism led to a temporary eclipse of late Baroque masters. However, the 20th century witnessed a significant reappraisal of his work. Scholarly research and major exhibitions, particularly one organized by an international team in 1974 focusing on his work in the Piarist Church, brought his extraordinary achievements back into the spotlight.

Today, Maulbertsch is recognized as a pivotal figure in Central European art history. He stands alongside other great Austrian Baroque painters like his early influence Paul Troger or his slightly later contemporary Martin Johann Schmidt (known as Kremser Schmidt), but his style remains unique in its intensity and coloristic brilliance. He is seen as the foremost exponent of a specifically Austrian iteration of the late Baroque and Rococo, successfully translating the grandeur of the Italian tradition, particularly Venetian colorito exemplified by Tiepolo and Piazzetta, into a deeply personal and emotionally charged visual language. His work bridges the gap between the High Baroque and the nascent Neoclassical era, leaving behind a legacy of breathtaking visual experiences in the churches and palaces he adorned.

Legacy and Enduring Importance

Franz Anton Maulbertsch's legacy is multifaceted. Primarily, it resides in the stunning fresco cycles that transformed numerous sacred and secular spaces across Central Europe into vibrant theaters of faith and allegory. His mastery of the fresco technique, combined with his unique artistic vision, produced works of enduring power and beauty. He demonstrated an unparalleled ability to orchestrate vast, complex compositions filled with dynamic movement, intense emotion, and dazzling light and color effects.

His influence extended through his workshop and students like Joseph Winterhalder, ensuring the continuation of his stylistic approach for a time. While perhaps not as widely known internationally as some Italian or French masters of the period, or even earlier Baroque giants like Peter Paul Rubens or Rembrandt van Rijn whose approaches differed significantly, Maulbertsch holds a crucial place within the specific context of 18th-century Habsburg art.

The rediscovery and scholarly appreciation of his work in the 20th century have solidified his status as a major master. His paintings and frescoes are now essential points of reference for understanding the late Baroque and Rococo north of the Alps. His willingness to experiment with color, his expressive intensity, and his ability to convey profound spiritual and intellectual themes make his work continually relevant and fascinating for study and appreciation. He remains a testament to the artistic vitality of Vienna and the broader Central European region during the final flowering of the Baroque era.

Conclusion

Franz Anton Maulbertsch was more than just a prolific decorator; he was an artist of profound originality and emotional depth. Born Austrian, trained in Vienna, and deeply influenced by the Venetian school – particularly masters like Piazzetta, Pittoni, Ricci, and the great Tiepolo – he forged a unique style characterized by dramatic energy, bold color, and intense spirituality. His frescoes, scattered across the former Habsburg lands, represent the pinnacle of late Baroque ceiling painting in Central Europe. From the early brilliance of the Piaristenkirche in Vienna to the late majesty of the Strahov Library in Prague, his works captivate with their dynamism and expressive power. Though his fame waned after his death, his rediscovery has rightfully placed him among the essential masters of the 18th century, a vital link between the Italian Baroque and the distinct artistic identity of Central Europe. His legacy endures in the breathtaking beauty and spiritual intensity of the spaces he transformed with his art.