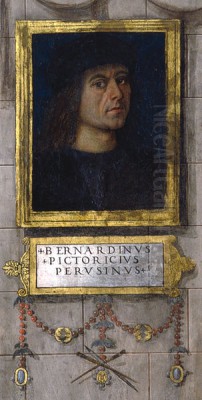

Bernardino di Betto, more famously known by his nickname Pinturicchio (sometimes spelled Pintoricchio), meaning "little painter," was a significant figure in Italian Renaissance art, particularly celebrated for his vibrant and richly detailed fresco cycles. Active primarily in Umbria, Rome, and Siena, his work exemplifies the decorative splendor and narrative clarity prized during the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. Though sometimes overshadowed in historical accounts by giants like Raphael or Michelangelo, Pinturicchio carved a distinct niche for himself, leaving an indelible mark on some of the most important chapels and apartments of his era.

Early Life and Umbrian Roots

Born in Perugia around 1454 (though some sources suggest a slightly later date, perhaps 1456), Bernardino di Betto Betti Biagio emerged from the artistically fertile region of Umbria. Perugia, at this time, was a bustling center of artistic activity, fostering a school of painting characterized by its gentle lyricism, clear compositions, and often serene landscapes. It is widely accepted that Pinturicchio received his formative training in this environment, likely within the workshop of the preeminent Umbrian master, Pietro Perugino.

The influence of Perugino is palpable in Pinturicchio's early works, evident in the figural types, the harmonious arrangement of compositions, and the soft, atmospheric quality of his backgrounds. Other Perugian painters active during this period, such as Fiorenzo di Lorenzo and Benedetto Bonfigli, also contributed to the local artistic milieu that would have shaped the young Pinturicchio. He formally joined the Perugian painters' guild around 1481, a testament to his established skill and professional standing by that time. His early career was marked by a steady development of his own voice, building upon the Umbrian foundations.

Roman Commissions and Rising Fame

The 1480s marked a pivotal period for Pinturicchio as he, alongside Perugino and other leading artists of the day, was summoned to Rome. This call was for one of the most prestigious artistic undertakings of the Renaissance: the decoration of the newly constructed Sistine Chapel in the Vatican for Pope Sixtus IV. Pinturicchio is documented as collaborating with Perugino on frescoes here between 1481 and 1482. While Perugino was the lead master for their section, Pinturicchio's hand is confidently identified in parts of scenes such as The Journey of Moses in Egypt and The Baptism of Christ.

Working alongside other masters like Sandro Botticelli, Domenico Ghirlandaio, Cosimo Rosselli, and Luca Signorelli on the Sistine Chapel walls provided invaluable experience and exposure. This project placed Pinturicchio at the heart of the Renaissance art world, allowing him to absorb diverse stylistic influences and to demonstrate his capabilities to powerful patrons. His contribution, though under Perugino's direction, showcased his burgeoning talent for intricate detail and lively narrative, qualities that would become hallmarks of his independent career.

Following the Sistine Chapel project, Pinturicchio began to receive significant independent commissions in Rome. One of his earliest major independent fresco cycles was for the Bufalini Chapel in the Basilica of Santa Maria in Aracoeli, completed around 1484-1486. These frescoes depict scenes from the life of Saint Bernardino of Siena, a commission that resonated with his own name. Here, Pinturicchio demonstrated a growing confidence, with dynamic compositions, expressive figures, and a rich tapestry of architectural and landscape details. The works show a clear narrative progression and a keen eye for contemporary costume and portraiture, often including figures of his patrons and their associates.

He also undertook important commissions for influential cardinals. For Cardinal Domenico della Rovere, he decorated a chapel in the Basilica di Santa Maria del Popolo around 1488-1490, featuring the Adoration of the Child with St. Jerome. For Cardinal Giuliano della Rovere (later Pope Julius II), he also worked in Santa Maria del Popolo, in the Basso Della Rovere Chapel, painting an altarpiece of the Madonna and Child Enthroned with Saints and other frescoes. These works further solidified his reputation in Rome as a skilled and reliable master of fresco. His style was characterized by a bright palette, an abundance of gold leaf and applied decoration (like pastiglia, or raised gesso), and a charming, almost storybook quality that appealed greatly to his patrons.

The Splendor of the Borgia Apartments

Perhaps Pinturicchio's most famous and ambitious Roman project was the decoration of the Borgia Apartments in the Vatican Palace for Pope Alexander VI (Rodrigo Borgia). Executed between 1492 and 1494, this extensive cycle of frescoes transformed a suite of six rooms into a lavish testament to the Pope's power, learning, and piety, albeit through a highly personalized and often esoteric iconographic program.

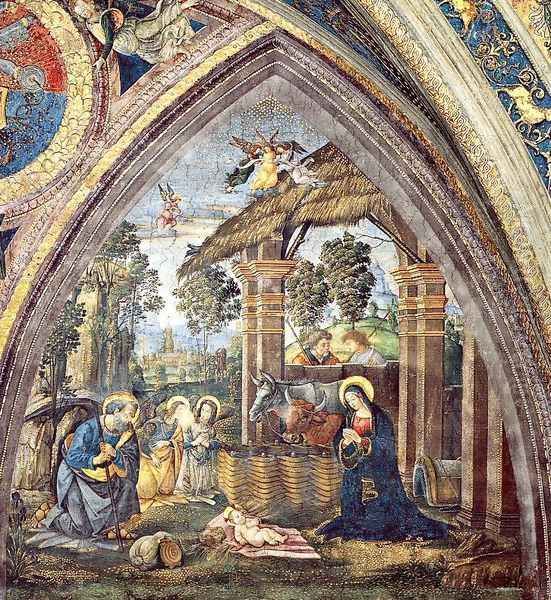

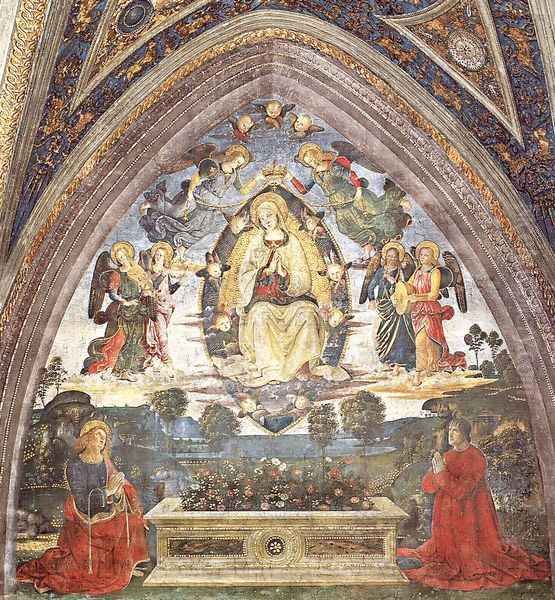

The rooms included the Hall of the Mysteries of the Faith, the Hall of the Saints, and the Hall of the Liberal Arts, among others. Pinturicchio and his workshop filled these spaces with a dazzling array of imagery. The Hall of the Mysteries, for example, features scenes like the Annunciation, Nativity, Adoration of the Magi, Resurrection (which notably includes a portrait of Alexander VI kneeling in prayer), Ascension, Pentecost, and Assumption of the Virgin. The Hall of the Saints depicts episodes from the lives of various saints, including Saint Catherine of Alexandria, whose disputation with the philosophers before Emperor Maxentius is a particularly vibrant and crowded scene, thought to contain portraits of Lucrezia Borgia as Catherine and other members of the Borgia circle.

The decorative scheme was incredibly rich, incorporating not only narrative scenes but also elaborate grotesques inspired by recently rediscovered ancient Roman paintings (like those in Nero's Domus Aurea), intricate patterns, Borgia family emblems (such as the bull), and extensive use of gold and ultramarine blue. This created an atmosphere of unparalleled opulence. Pinturicchio's skill in organizing these complex iconographic programs and managing a large workshop to execute them efficiently was remarkable. Artists like Antoniazzo Romano were also active in Rome at this time, but Pinturicchio's particular flair for the decorative and the narrative set his Borgia Apartment frescoes apart.

Sienese Masterpieces: The Piccolomini Library

After his extensive work in Rome, Pinturicchio's career took him to Siena, another prominent artistic center. His most significant Sienese commission, and one of the crowning achievements of his career, was the fresco cycle for the Piccolomini Library in the Siena Cathedral. This project was commissioned by Cardinal Francesco Todeschini Piccolomini (later Pope Pius III, though his papacy was very brief) to honor the life and achievements of his uncle, Aeneas Silvius Piccolomini, who had reigned as Pope Pius II.

Executed between 1502 and 1507/08, the ten large frescoes lining the walls of the library recount key episodes from Pius II's remarkably varied life – as a scholar, poet, diplomat, and finally, Pope. The scenes are rendered with Pinturicchio's characteristic vibrancy, clarity, and attention to detail. They depict events such as Aeneas Silvius at the Council of Basel, his meeting with Emperor Frederick III, his elevation to Cardinal, and his coronation as Pope. The frescoes are notable for their bright, almost luminous colors, their panoramic landscapes, detailed architectural settings, and the lively depiction of crowds, processions, and ceremonies.

A fascinating aspect of the Piccolomini Library project is the documented, albeit debated, involvement of the young Raphael Sanzio. Giorgio Vasari, the 16th-century artist and biographer, states that Raphael provided some drawings and cartoons for the frescoes. While the extent of Raphael's contribution is still discussed by scholars, it is generally accepted that he did play a role, perhaps as a talented assistant in Pinturicchio's workshop, before his own meteoric rise to fame. The compositions in the Piccolomini Library, while clearly bearing Pinturicchio's stylistic signature, do possess a certain compositional grace and figural elegance that some attribute to Raphael's youthful genius. Regardless of the exact division of labor, the Piccolomini Library stands as a magnificent example of Renaissance narrative fresco painting.

While in Siena, Pinturicchio also undertook other commissions, including frescoes for the Chapel of Saint John the Baptist in the Siena Cathedral around 1504, depicting eight scenes from the saint's life. These further demonstrate his mastery of narrative and his ability to adapt his style to different sacred spaces. His Sienese period shows a continued refinement of his skills, maintaining his decorative richness while also engaging with the evolving artistic currents of the early 16th century.

Other Notable Works and Panel Paintings

While Pinturicchio is primarily celebrated for his frescoes, he also produced a number of significant panel paintings. Among these is the Santa Maria dei Fossi Altarpiece, painted for a church in Perugia around 1496-1498. This large polyptych, now in the Galleria Nazionale dell'Umbria, features a central panel of the Madonna and Child with the Infant St. John the Baptist, surrounded by saints and scenes from the life of Christ. It showcases his skill in oil and tempera, with the same attention to detail, rich coloration, and gentle figural types found in his frescoes.

His Portrait of a Boy (Knabenbildnis), now in the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister in Dresden, is a sensitive and engaging work, demonstrating his abilities in portraiture. He also painted other Madonnas, such as the Madonna of Peace (Madonna della Pace) for San Severino Marche, and various smaller devotional panels. These works, while perhaps less grand in scale than his fresco cycles, are important for understanding the full range of his artistic output and his contribution to the Umbrian tradition of panel painting, a tradition also enriched by artists like Giovanni Bocciati.

His workshop was evidently prolific, and attributions can sometimes be complex, with assistants likely playing significant roles in the execution of larger commissions. However, the guiding artistic vision and the distinctive stylistic traits evident in the major works are unmistakably Pinturicchio's.

Artistic Style, Techniques, and Anecdotes

Pinturicchio's style is defined by several key characteristics. He possessed an exceptional talent for narrative, making complex stories accessible and engaging through clear compositions and expressive figures. His use of color was consistently vibrant and rich, often employing expensive pigments like lapis lazuli for blues and generous amounts of gold leaf to highlight details and create a sense of luxury. This lavish use of gold, sometimes criticized by later commentators like Vasari as being somewhat old-fashioned or ostentatious, was highly prized by his patrons and contributed significantly to the splendor of his decorative schemes.

He was a master of detail, meticulously rendering costumes, textiles, architectural elements, and landscape features. His works often include charming anecdotal details and lively secondary figures that add to the richness of the scene. He was also adept at incorporating classical motifs, including grotesques, putti, and architectural forms inspired by antiquity, reflecting the Renaissance fascination with the classical past. This interest was shared by contemporaries like Andrea Mantegna, though Mantegna's approach was often more rigorously archaeological.

The nickname "Pinturicchio" (little painter) is said to have referred to his small physical stature. Giorgio Vasari, in his Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, provides some colorful, if not always entirely reliable, anecdotes about Pinturicchio. Vasari portrays him as somewhat grasping and eager for fame and fortune. One famous story recounts an incident during his work at the monastery of San Francesco in Siena, where he allegedly pestered the friars to remove a large, old chest from a room he was to paint, claiming it was in his way. When the friars finally moved it, they supposedly discovered a hidden cache of 500 gold ducats, which Vasari implies Pinturicchio had hoped to claim. Such stories, while entertaining, should be treated with caution, as Vasari often had his own biases and agendas. For instance, Vasari, a strong proponent of Florentine artistic primacy, sometimes downplayed the achievements of artists from other regions or those whose style he considered less "modern" than that of Michelangelo or Raphael.

Despite Vasari's sometimes critical tone, he did acknowledge Pinturicchio's skill and diligence. The sheer volume of high-quality work Pinturicchio produced attests to his industriousness and the efficiency of his workshop. He was clearly a highly sought-after artist, capable of satisfying the demands of the most powerful and discerning patrons of his time, including popes and cardinals.

Relationships with Contemporaries

Pinturicchio's career was interwoven with those of many other prominent artists. His foundational relationship was with Perugino, evolving from a likely apprenticeship to a collaborative partnership. While Perugino's influence remained a constant thread, Pinturicchio developed a more overtly decorative and narratively dense style.

His interaction with the young Raphael in Siena is a significant point, highlighting the master-assistant dynamics common in Renaissance workshops. It suggests that even established masters like Pinturicchio were open to incorporating the talents of promising younger artists.

In Rome, he worked alongside a constellation of stars on the Sistine Chapel walls, including Botticelli, Ghirlandaio, and Signorelli. While their styles differed – Signorelli's work, for example, was characterized by a powerful, muscular dynamism quite distinct from Pinturicchio's more graceful and ornamental approach – this collaborative environment fostered an exchange of ideas and techniques. He would have also been aware of the work of other artists active in Rome, such as Melozzo da Forlì, known for his mastery of perspective and monumental figures, and Filippino Lippi, another master of expressive narrative fresco.

The competitive nature of the art market meant that artists were constantly vying for commissions. Pinturicchio's success in securing major projects like the Borgia Apartments and the Piccolomini Library in the face of such competition speaks volumes about his reputation and the appeal of his particular artistic vision.

Later Years, Death, and Legacy

Pinturicchio continued to work into the early 16th century, primarily in Siena and Umbria. His later works, such as the frescoes for Pandolfo Petrucci in his Sienese palace (including the Return of Odysseus scene, now in the National Gallery, London), show him engaging with mythological themes and demonstrating a continued vitality.

He died in Siena on December 11, 1513, at the age of approximately 59, and was buried there. Vasari recounts a rather bleak story about his death, suggesting he was abandoned by his wife, Grania, and died of starvation and neglect. However, like many of Vasari's more dramatic tales, this should be viewed with skepticism, as other evidence is lacking.

Pinturicchio's legacy is significant. In his own time, he was immensely popular, and his decorative style had a considerable impact, particularly on Sienese painting and the broader tradition of ornamental fresco work. While his reputation waned somewhat in the centuries following his death, particularly as tastes shifted towards the High Renaissance classicism of Raphael and Michelangelo and later the drama of the Baroque, modern art history has re-evaluated his contributions.

He is now recognized as a highly original and skilled master who perfectly captured the taste for opulent decoration and engaging storytelling prevalent in late 15th and early 16th-century Italy. His ability to manage large-scale commissions, his innovative use of decorative motifs, and the sheer visual delight of his frescoes secure his place as an important figure in the Italian Renaissance. His work provides a vibrant window into the cultural and religious life of the period, and his great fresco cycles in Rome and Siena remain among the most captivating artistic ensembles of their time. Artists like Benozzo Gozzoli, from an earlier generation, had also excelled in creating extensive, decorative fresco cycles (e.g., the Magi Chapel in Florence), and Pinturicchio can be seen as a brilliant successor in this tradition of painterly storytelling on a grand scale.

Conclusion

Bernardino di Betto, "Pinturicchio," was far more than just a "little painter." He was a master of narrative, a brilliant colorist, and an orchestrator of some of the most splendid decorative schemes of the Renaissance. From the hallowed walls of the Sistine Chapel and the lavish Borgia Apartments in Rome to the magnificent Piccolomini Library in Siena, his frescoes brought stories to life with unparalleled vibrancy and detail. Influenced by the Umbrian school and his master Perugino, he forged a unique style that captivated popes, cardinals, and civic patrons. His collaborations, including with the young Raphael, and his interactions with the leading artists of his day place him firmly within the dynamic artistic currents of the Renaissance. Though subject to the shifting tides of art historical opinion, Pinturicchio's enduring legacy lies in the joyful, intricate, and richly adorned worlds he created, which continue to enchant and inform viewers today.