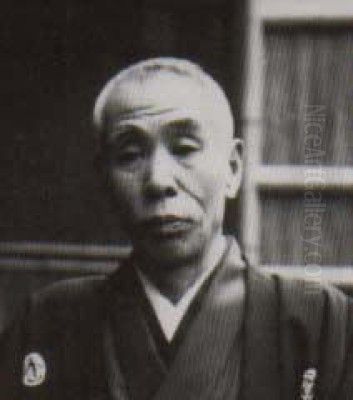

Takeuchi Seiho stands as a monumental figure in the annals of Japanese art, a painter whose innovative spirit and profound skill bridged the tumultuous transition from the Meiji era's fervent modernization to the Showa period's evolving cultural landscape. His original name was Tsunekichi , with "Seiho" being his art name, or gō, under which he achieved enduring fame. Born in the ancient capital of Kyoto, a city steeped in artistic tradition, Seiho became a pivotal force in the development of Nihonga, or modern Japanese-style painting, skillfully amalgamating traditional Japanese aesthetics with Western artistic techniques. His influence extended far beyond his own canvases, shaping the Kyoto art world (Kyō-gadan) for decades through his teaching and the sheer brilliance of his artistic vision.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Kyoto

Born on November 22, 1864, in Kyoto, Takeuchi Tsunekichi was the eldest son of a family that ran a prominent traditional restaurant, or ryotei, named "Kamese." In a society where familial duty often dictated one's path, the expectation was for Tsunekichi to inherit the family business. However, from a young age, he displayed an undeniable passion and talent for drawing, a calling that diverged sharply from the culinary world. Fortunately, his deep affection for art was recognized, and his younger sister reportedly agreed to take over the family enterprise, freeing Seiho to pursue his artistic inclinations. This familial support was crucial in allowing him to dedicate his life to painting.

Kyoto, with its rich tapestry of temples, shrines, classical gardens, and established artistic lineages, provided an fertile environment for a budding artist. Seiho's formal artistic training began around the age of 13, when he started studying under Tsuchida Eirin , a painter connected to his family. This initial tutelage laid a foundation in traditional painting techniques. However, a more formative period of his education commenced at the age of 17, when he became a disciple of Kōno Bairei .

Under the Wing of Kōno Bairei: The Shijō School and Beyond

Kōno Bairei was a leading figure of the Shijō school in Kyoto, a style known for its emphasis on direct observation from nature, a departure from the more stylized conventions of older schools like the Kanō. The Shijō school, itself an offshoot of the Maruyama school founded by Maruyama Ōkyo , championed a form of naturalistic representation combined with traditional Japanese brushwork and poetic sensibility. Bairei was a demanding teacher, and under his guidance, Seiho honed his skills in sketching from life (shasei), a practice that would remain central to his art throughout his career.

Seiho quickly distinguished himself among Bairei's students, becoming one of the "Four Heavenly Kings of Bairei's studio" , a testament to his prodigious talent. Beyond the Shijō school's curriculum, Bairei also encouraged his students to study a wide range of historical Japanese painting styles. Seiho immersed himself in copying masterpieces from the Kanō school , known for its bold ink work and decorative compositions, and the ink wash traditions of Muromachi period masters like Sesshū Tōyō and Sōami . This broad education provided him with a versatile technical arsenal and a deep understanding of Japan's artistic heritage. In 1883, he also enrolled in the Kyoto Prefectural School of Painting , further broadening his formal artistic education.

The relationship with Kōno Bairei extended beyond a typical master-disciple dynamic. Seiho would eventually marry Bairei's eldest daughter, further cementing his ties to this influential artistic lineage. This connection undoubtedly provided him with support and opportunities within the Kyoto art establishment.

A Transformative Sojourn: Europe and the Dawn of a New Style

The Meiji era (1868-1912) was a period of intense Westernization in Japan, and the art world was no exception. While some artists embraced Western oil painting (Yōga) wholesale, others sought to revitalize traditional Japanese painting (Nihonga) by incorporating Western techniques and perspectives. Seiho emerged as a leading figure in this latter movement. A crucial turning point in his artistic development was his journey to Europe in 1900-1901, primarily to visit the Exposition Universelle in Paris.

This seven-month sojourn exposed Seiho to a vast array of Western art, both historical and contemporary. He was particularly captivated by the atmospheric landscapes of the British Romantic painter J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851) and the gentle, naturalistic scenes of the French Barbizon school painter Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796-1875). The realism and observational acuity of these artists resonated with his own Shijō school training, which emphasized sketching from life. He also encountered the work of academic painters like Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904), who reportedly showed Seiho detailed anatomical studies of lions, a subject that would later feature prominently in Seiho's oeuvre. The vibrant brushwork and light effects of Impressionist painters like Claude Monet (1840-1926) and Camille Pissarro (1830-1903) also likely contributed to his evolving understanding of light and color.

Upon his return to Japan, Seiho began to synthesize these Western influences with his deep grounding in Japanese tradition. He did not simply imitate Western styles but rather selectively adopted elements—such as perspective, chiaroscuro, and a more analytical approach to form—to enrich and modernize Nihonga. This fusion resulted in a fresh, vibrant, and remarkably realistic style that captivated audiences and set a new direction for Japanese painting.

Forging a New Path: Seiho's Mature Style and Thematic Concerns

Seiho's post-European style was characterized by its sophisticated blend of Eastern and Western techniques. He retained the traditional Japanese materials of ink and mineral pigments on silk or paper, as well as the emphasis on brushwork and empty space (ma). However, his approach to subject matter became more dynamic and three-dimensional. He was a master of capturing the essence of his subjects, whether they were animals, landscapes, or human figures, with an uncanny sense of vitality and presence.

Animals were a recurring and beloved theme in Seiho's work. He painted them not as mere symbols or decorative motifs, but as living, breathing creatures with individual personalities. His depictions of lions, tigers, monkeys, rabbits, and birds are renowned for their anatomical accuracy—a skill honed through meticulous sketching and, in the case of exotic animals, visits to zoos and even circuses. His famous painting Lion , created after his European trip, showcases this newfound realism and power, a departure from more stylized traditional depictions.

Landscapes also figured prominently in his work, ranging from serene views of Kyoto's natural beauty to more dramatic and atmospheric scenes. He had a remarkable ability to convey the mood and atmosphere of a place, using subtle gradations of ink and color to evoke mist, rain, or the gentle light of dawn or dusk. His work often displayed a keen sensitivity to the changing seasons, a traditional theme in Japanese art.

Seiho's technical virtuosity was legendary. He was adept at various brush techniques, from fine, delicate lines to broad, expressive washes. He also experimented with different pigments and application methods to achieve unique textures and color effects. His innovative spirit extended to composition, often employing dynamic arrangements and unusual perspectives that added a modern sensibility to his work.

Masterpieces and Signature Works: A Legacy in Art

Seiho Takeuchi's prolific career yielded numerous masterpieces that are now treasured in collections worldwide. Among his most celebrated works is Tabby Cat , also sometimes referred to as Spotted Cat or Cat on a Board , painted around 1924 and now housed in the Yamatane Museum of Art. This iconic painting depicts a green-eyed tabby cat with remarkable realism and psychological depth, capturing the feline's alert yet relaxed posture. The meticulous rendering of the fur and the intense gaze of the cat make it a tour-de-force of animal portraiture.

Another early work that garnered international attention was Sparrows in the Snow , which received a silver medal at the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893, even before his European trip, signaling his early promise. His monumental Lion , exhibited after his return from Europe, won a gold prize in Japan and demonstrated his successful integration of Western realism into a powerful Nihonga framework.

The painting First Picture of the Year , created in 1913 (some sources say 1920, but 1913 is more commonly cited for a work of this title that marked a stylistic shift), is often considered a turning point, showcasing his mature style that masterfully blended observation with artistic interpretation. Other notable works include Yasaka Pagoda , capturing a famous Kyoto landmark, and Whirlpool in Naruto , a dynamic seascape. His Snowy Dragon from 1913 is a powerful ink painting, while Great Lion Diagram further exemplifies his mastery of this majestic animal.

Later in his career, works like Spring Snow , painted in 1942, the year of his death, reveal a continued refinement and a poignant, lyrical quality. His series of Twelve Zodiac Signs , created around 1905-1906, demonstrates his versatility in depicting a range of animals with characteristic charm and insight. Even seemingly simple subjects, like Two Sparrows from 1898, are imbued with life and delicate beauty.

A Guiding Light: Seiho as an Educator and Mentor

Takeuchi Seiho's impact on Japanese art was amplified by his long and influential career as an educator. He believed deeply in nurturing the next generation of artists and played a crucial role in shaping the Kyoto art scene through his teaching. For approximately three decades, he taught at the Kyoto City School of Arts and Crafts , which later evolved into the Kyoto City Specialist School of Painting . His approach to teaching emphasized rigorous training in sketching from life, a deep understanding of traditional techniques, and an open-mindedness towards innovation.

In addition to his formal academic role, Seiho ran his own private art academy, or juku, called Chikujōkai . For nearly forty years, this studio became a vibrant hub for aspiring painters, and many of his students went on to become leading artists in their own right. Among his most distinguished pupils were Uemura Shōen , one of the most important female Nihonga painters, known for her elegant depictions of women; Tsuchida Bakusen , who, like Seiho, explored the fusion of Japanese and Western art; Ono Chikkyō , celebrated for his serene landscapes; and Nishiyama Suishō , who also became a prominent figure in the Kyoto art world.

Other notable artists who studied under Seiho or were significantly influenced by him include Hashimoto Kansetsu , known for his paintings of Chinese subjects and landscapes, and Roppu Terumine , also known as Yōhō, a talented female painter with whom Seiho had a close personal relationship. His legacy as a teacher is thus as significant as his own artistic output, ensuring the vitality and evolution of Nihonga in Kyoto for generations. His students, while absorbing his emphasis on realism and technical skill, were encouraged to develop their own individual styles, a testament to Seiho's enlightened approach to mentorship.

Seiho and His Contemporaries: A Dynamic Art World

Takeuchi Seiho operated within a dynamic and often competitive Japanese art world. In Tokyo, the dominant figure in Nihonga was Yokoyama Taikan . Taikan, along with artists like Hishida Shunsō and Shimomura Kanzan , was associated with the Japan Art Institute (Nihon Bijutsuin) and championed a different style of Nihonga, often characterized by its more romantic, idealized, and sometimes boneless (mōrōtai) technique. The phrase "Taikan of the East, Seiho of the West" became a common way to describe the two leading masters of modern Nihonga, highlighting their distinct regional and stylistic spheres of influence.

While their approaches differed, both Seiho and Taikan were committed to the modernization and revitalization of Japanese painting. They both served as jurors for the influential government-sponsored Bunten exhibitions (later Teiten and Shin-Bunten), which played a crucial role in shaping the direction of Japanese art during this period. Seiho's interactions were not limited to Nihonga painters. He was aware of the developments in Yōga (Western-style oil painting) and maintained connections with a broad spectrum of artists. In Kyoto, he was a central figure, interacting with other established painters like Tomioka Tessai , a master of Nanga (literati painting), though Tessai represented a more individualistic and less institutionally-aligned tradition.

The artistic environment was one of lively debate and experimentation, as artists grappled with how to define a modern Japanese artistic identity in a rapidly changing world. Seiho's ability to innovate while remaining rooted in tradition made him a respected and influential voice in these discussions. His students, such as Tsuchida Bakusen, would go on to form their own groups, like the Kokuga Sōsaku Kyōkai (Society for the Creation of National Painting), further pushing the boundaries of Nihonga, sometimes in directions that diverged from Seiho's own later, more conservative path, yet always acknowledging his foundational influence.

Personal Life and Unseen Influences

While much is known about Seiho's public artistic career, aspects of his personal life remain more private, as is common with historical figures from that era. He was born into a merchant family, and his decision to pursue art was a significant departure from that background. His marriage into Kōno Bairei's family provided stability and connections.

A more complex and less publicly discussed aspect of his life was his relationship with the painter Roppu Terumine, also known as Yōhō. She was one of his students and a talented artist in her own right. Sources suggest that their relationship was intimate and that they had several children together. According to some accounts, they had seven children; five sons were adopted out to other families, a practice not uncommon at the time for various social reasons, while a daughter remained with them but sadly passed away at a young age. Such personal circumstances, while often veiled, inevitably shape an artist's life and, perhaps subtly, their work. Yōhō's own artistic career, though promising, may have been overshadowed or complicated by her relationship with her famous mentor.

Seiho's dedication to his art was all-consuming. His studio, Chikujōkai, was not just a place of teaching but also his primary domain for creation. He was known for his intense focus and meticulous preparation, often making numerous sketches before starting a final painting. This disciplined approach, combined with his innate talent, was the bedrock of his artistic success.

Recognition, Honors, and Later Years

Takeuchi Seiho's contributions to Japanese art were widely recognized during his lifetime. He received numerous accolades and held prestigious positions. In 1907, he was appointed as a juror for the first Bunten exhibition, the official government-sponsored art exhibition, a role he would continue to play in subsequent iterations, solidifying his status as an arbiter of artistic taste. He was also appointed as an Imperial Household Artist in 1913, an honor bestowed upon the most distinguished artists and craftsmen in Japan, signifying imperial patronage and national recognition.

The culmination of his official honors came in 1937, when he was one of the first recipients of the prestigious Order of Culture , awarded by the Japanese government for outstanding contributions to arts, literature, science, or technology. This was the highest honor an artist could receive and a testament to his immense impact on Japanese culture.

In his later years, Seiho continued to paint with undiminished skill, though his works sometimes took on a more introspective and refined quality. He remained a revered figure in the Kyoto art world, a living link to the traditions of the past and a beacon for the future of Nihonga. His influence was pervasive, not only through his direct students but also through the broader artistic climate he helped to create. He passed away on August 23, 1942, at the age of 77, leaving behind a rich and varied body of work and an indelible mark on the history of Japanese art.

The Enduring Legacy of Seiho Takeuchi

Takeuchi Seiho's legacy is multifaceted. As an artist, he demonstrated that Nihonga could be a vibrant and evolving art form, capable of engaging with modern sensibilities without sacrificing its unique cultural identity. His masterful fusion of Japanese tradition and Western realism provided a compelling model for other artists and helped to steer Nihonga through a critical period of transformation. His paintings continue to be admired for their technical brilliance, their keen observation of nature, and their profound artistic sensibility.

As an educator, Seiho nurtured several generations of Kyoto painters, ensuring the continuity and dynamism of the Kyō-gadan. His students, including luminaries like Uemura Shōen, Tsuchida Bakusen, and Ono Chikkyō, went on to forge their own significant careers, each contributing to the rich tapestry of 20th-century Japanese art. The emphasis he placed on shasei (sketching from life) remains a cornerstone of artistic training in many Nihonga circles.

Today, Seiho Takeuchi is celebrated as one of the "twin giants" of modern Nihonga, alongside Yokoyama Taikan. His works are prominently featured in major museum collections in Japan and internationally, and retrospective exhibitions continue to draw large audiences, reaffirming his status as a beloved and historically significant painter. His ability to capture the spirit of his subjects, particularly animals, with such empathy and precision, ensures that his art remains accessible and engaging to contemporary viewers. He was a true innovator who respected tradition, a master technician with a poet's soul, and a pivotal figure who helped to define the course of modern Japanese art. His influence is still felt, and his paintings continue to inspire awe and admiration, securing his place as an immortal in the world of art.