Toshiyuki Hasegawa stands as one of Japan's most compelling and tragic modern painters, a figure whose life and art burned with a fierce, untamed intensity. Active primarily during the Taishō (1912-1926) and early Shōwa (1926-1989) periods, Hasegawa's work is characterized by its raw emotional power, vibrant color palette, and a deeply personal expressionism that set him apart from many of his contemporaries. His art, often created in the throes of poverty and personal struggle, offers a poignant glimpse into the underbelly of a rapidly modernizing Japan and the soul of an artist who lived on the fringes.

Early Life and Artistic Stirrings

Born in 1891 in a village that is now part of Yokohama, Kanagawa Prefecture, Toshiyuki Hasegawa's early life remains somewhat shrouded in obscurity, a common trait for artists who later achieve posthumous fame without having meticulously documented their beginnings. It is known that he moved to Kyoto to study traditional Japanese painting (Nihonga) at the Kyoto Municipal School of Arts and Crafts, but he did not complete his studies there. This early exposure to traditional techniques, however, may have provided a foundational understanding of form and composition, even as he later veered dramatically towards Western-style oil painting (Yōga).

His formative years were marked by a restless spirit. He reportedly worked various jobs, including as a newspaper reporter and an elementary school teacher, before dedicating himself more fully to art. This period of wandering and varied experiences likely contributed to his empathetic portrayal of ordinary people and the gritty urban landscapes that would later define his oeuvre. Unlike artists who came from privileged backgrounds or found early patronage, Hasegawa's path was one of struggle, a reality that would deeply permeate his artistic vision.

The Allure of Tokyo and the Development of a Unique Style

The true crucible for Hasegawa's art was Tokyo. He moved to the capital, immersing himself in its vibrant, chaotic, and rapidly changing environment. The city, particularly its working-class districts like Asakusa and Shinjuku, became his muse. It was here that Hasegawa forged his distinctive style, heavily influenced by European Post-Impressionism and Fauvism, yet uniquely his own. Artists like Vincent van Gogh, with his passionate brushwork and emotional intensity, and the Fauves, such as Henri Matisse and André Derain, with their bold, non-naturalistic use of color, resonated deeply with Hasegawa's temperament.

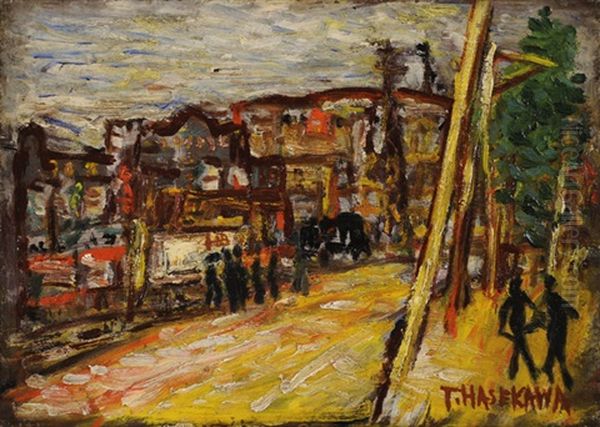

Hasegawa's paintings are characterized by thick impasto, where paint is applied so heavily that brushstrokes are clearly visible, giving the canvas a textured, almost sculptural quality. His colors are often vivid and clashing, chosen not for their representational accuracy but for their emotional impact. This approach was a departure from the more academic styles prevalent at the time and aligned him with a more avant-garde sensibility that was emerging in Japan, influenced by artists like Ryusei Kishida, who also explored intense personal expression, albeit in a different manner.

He was largely self-taught in the Western oil painting techniques he adopted, learning through observation, experimentation, and an innate understanding of the medium's expressive potential. This lack of formal, prolonged academic training in Yōga perhaps contributed to the raw, unpolished, and direct quality of his work, which eschewed refined finishes for immediate emotional communication.

Subject Matter: The Urban Landscape and Its Denizens

Hasegawa's primary subjects were the cityscapes of Tokyo, the people he encountered in its bars and streets, still lifes often composed of simple, everyday objects, and powerful self-portraits. His urban landscapes are not picturesque postcard views but rather dynamic, sometimes unsettling, depictions of a city in flux. He captured the energy of areas like Shinjuku, with its burgeoning modernity, and the more traditional, earthy atmosphere of Asakusa. Works like Shinjuku Landscape or View of Asakusa pulsate with life, the buildings and streets rendered with an almost frantic energy.

His portraits and figure studies often depict individuals from the margins of society – bar hostesses, laborers, and fellow drinkers. These are not idealized figures but are imbued with a sense of lived experience, often tinged with melancholy or a defiant vitality. His empathy for these subjects is palpable, reflecting his own precarious existence. He painted people he knew, people who, like him, navigated the complexities of urban life. This focus on the common person and the urban environment can be seen as a parallel to the work of some European expressionists, such as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner or George Grosz, who also depicted the vibrant and often harsh realities of city life.

Still lifes, too, were a significant part of his output. Objects like a bottle of sake, a fish, or a simple flower arrangement would be transformed by his vigorous brushwork and intense color into potent symbols of existence. These were not mere academic exercises but deeply felt expressions, often reflecting his immediate surroundings and limited means.

Representative Masterpieces

Several works stand out in Toshiyuki Hasegawa's oeuvre, each encapsulating different facets of his artistic genius.

Cafe Waitress (Kissa no Jokyū) is one of his most iconic paintings. The subject, a waitress, is rendered with bold strokes and a vibrant, almost jarring, color palette. Her expression is enigmatic, a mixture of weariness and resilience. The painting captures the atmosphere of a typical urban café of the era, a meeting place for artists, writers, and ordinary city dwellers. The directness of her gaze and the intensity of the colors make it a compelling psychological portrait.

Tank Car (Tanku sha) is another powerful piece, showcasing his ability to find beauty and dynamism in industrial subjects. The painting depicts a railway tank car, a symbol of modernization, rendered with thick, energetic brushstrokes and a dramatic use of light and shadow. It’s a testament to his fascination with the changing urban and industrial landscape of Tokyo.

His Self-Portrait with a Pipe is a raw and unflinching look at himself. The artist confronts the viewer with an intense, searching gaze. The colors are somber, and the brushwork is characteristically vigorous, conveying a sense of inner turmoil and a rugged determination. Self-portraits were a recurring theme, allowing him to explore his own identity and psychological state, much like Rembrandt or Van Gogh did centuries and decades before him, respectively.

Other notable works include Nakamoto, a portrait of a fellow artist, and The Drunkard's Song (Sake), which vividly captures the atmosphere of a drinking establishment and perhaps reflects his own struggles with alcohol. Each piece, whether a landscape, portrait, or still life, is imbued with his unmistakable energy and emotional depth.

The Bohemian Existence: A Life on the Edge

Hasegawa's life was the epitome of the bohemian artist. He lived in extreme poverty, often struggling for basic necessities. He was known to frequent cheap bars, trading paintings for food and drink. His disheveled appearance and eccentric behavior became part of his legend. This lifestyle, while contributing to the raw authenticity of his art, also took a heavy toll on his health.

He was a solitary figure in many ways, though he did associate with other artists and participated in some exhibitions, notably with the Nika-kai (Second Division Society) and later with the Dokuritsu Bijutsu Kyokai (Independent Art Association), which provided platforms for more avant-garde and individualistic artists. However, he never quite fit into any particular group or movement, preferring to follow his own uncompromising path. His contemporaries included artists like Sotaro Yasui and Seiji Togo, who were also exploring modern Western styles but often with a greater degree of commercial success or academic acceptance than Hasegawa achieved in his lifetime.

His struggles with alcoholism were profound and ultimately contributed to his early death. This tragic aspect of his life often colors the perception of his work, casting him in the mold of the "poète maudit" or cursed poet/artist, a figure who sacrifices well-being for art. While there is truth to this, it's important not to let the biography overshadow the intrinsic artistic merit of his paintings.

Artistic Influences and Context

Hasegawa's art did not develop in a vacuum. The Taishō and early Shōwa periods were times of immense cultural ferment in Japan. The country was rapidly modernizing and absorbing Western influences in all fields, including art. Artists traveled to Europe, particularly Paris, and brought back firsthand knowledge of Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, Cubism, and Surrealism. Figures like Tsuguharu Foujita, who achieved international fame, and Yasuo Kuniyoshi, who became prominent in the American art scene, were part of this wave of Japanese artists engaging with global modernism.

Within Japan, art schools and associations debated the direction of Japanese art. While some championed the preservation and evolution of traditional Nihonga, others, like Hasegawa, embraced Yōga. His work can be seen as part of a broader movement of Japanese artists seeking to create a modern art that was both international in its language and deeply personal, if not always overtly "Japanese," in its expression.

The influence of Van Gogh is perhaps the most frequently cited in relation to Hasegawa, and the parallels are evident in the emotional intensity, the visible brushwork, and the empathetic portrayal of humble subjects. However, Hasegawa was not a mere imitator. He absorbed these influences and synthesized them into a style that was uniquely his own, filtered through his personal experiences and the specific context of early 20th-century Tokyo. One might also see affinities with the expressive intensity of Norwegian painter Edvard Munch, or the raw, direct approach of French painter Chaïm Soutine, another artist who often depicted subjects with a visceral energy.

The Great Kantō Earthquake of 1923, which devastated Tokyo, also had a profound impact on the city and its artists. While Hasegawa's work doesn't always directly depict the destruction, the sense of a city in constant flux, rebuilding and transforming, is palpable in his urban landscapes. This period of reconstruction and social change provided a dynamic backdrop for his art.

Critical Reception and Posthumous Recognition

During his lifetime, Toshiyuki Hasegawa achieved a degree of recognition within avant-garde circles but little mainstream success or financial stability. His raw, unpolished style was not always appreciated by a public or critical establishment that often favored more refined or academically accomplished works. Some critics found his paintings crude or unfinished. However, others recognized the power and authenticity of his vision.

It was largely after his premature death in 1940 at the age of 49, from complications related to alcoholism and malnutrition, that his reputation began to grow significantly. Posthumous exhibitions and publications brought his work to a wider audience, and art historians began to reassess his contribution to modern Japanese art. He came to be seen as a pioneering figure of Japanese expressionism, an artist who, despite his personal demons, produced a body of work of remarkable power and originality.

Today, Hasegawa is regarded as one of the most important Yōga painters of his generation. His works are held in major museum collections in Japan, including the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, and the Yokohama Museum of Art. His life story, with its tragic elements, has also contributed to his enduring appeal, but it is the undeniable force of his paintings – their vibrant colors, their emotional honesty, and their dynamic energy – that secures his place in art history.

Artists like Kaita Murayama, another bohemian figure who died young, and Tetsugoro Yorozu, an early pioneer of Japanese modernism, shared some of Hasegawa's spirit of individualism and exploration of Western styles, though their artistic paths and expressions differed. Hasegawa's particular brand of raw, urban expressionism remains distinctive.

The Socio-Cultural Milieu of Taishō and Early Shōwa Japan

To fully appreciate Hasegawa's art, one must consider the socio-cultural environment of his time. The Taishō period was often characterized by a sense of liberalism and experimentation, known as "Taishō democracy." This era saw the rise of a vibrant popular culture, including cafes, cinemas, and new forms of literature and art. The "moga" (modern girl) and "mobo" (modern boy) symbolized the embrace of Western fashions and lifestyles.

However, this period was also marked by social unrest, economic disparities, and growing political tensions that would eventually lead to the militarism of the later Shōwa era. Hasegawa's art, with its focus on the gritty realities of urban life and the struggles of ordinary people, can be seen as a reflection of these underlying tensions. His paintings often convey a sense of unease and intensity that belies the more superficial gaiety of the "Taishō modern" image.

The "ero-guro-nansensu" (erotic-grotesque-nonsense) cultural trend, which explored the bizarre, the decadent, and the absurd, also flourished during this time. While Hasegawa's work is not explicitly part of this movement, his unflinching depiction of the less savory aspects of urban life and his own unconventional existence share a certain affinity with its anti-establishment spirit. He was, in essence, chronicling a side of modern Japanese life that was often overlooked or romanticized.

Hasegawa's Unique Technique and Vision

What makes Hasegawa's technique so compelling is its directness. He often painted quickly, alla prima, capturing his immediate impressions and emotions. His use of impasto was not just a stylistic choice but a way of conveying the physicality of his subjects and the intensity of his feelings. The paint itself becomes an active participant in the artwork, its texture and relief contributing to the overall impact.

His color choices, often non-naturalistic and bold, served an expressive purpose. A face might be rendered in greens and yellows, a sky in fiery oranges and reds, not because that is how they appeared in reality, but because those colors conveyed the emotional truth of the scene as Hasegawa experienced it. This subjective use of color is a hallmark of Expressionist art worldwide, from German Expressionists like Emil Nolde to French Fauvists.

His vision was one of empathy and raw honesty. He did not sentimentalize poverty or romanticize the bohemian lifestyle. Instead, he depicted it with an unflinching gaze, revealing both its hardships and its moments of fleeting beauty or camaraderie. This honesty is what gives his work its enduring power. He was not interested in creating conventionally "beautiful" paintings but in expressing fundamental human experiences.

Legacy and Enduring Impact

Toshiyuki Hasegawa's legacy is that of an artist who remained true to his own vision, despite immense personal difficulties. He demonstrated that powerful, authentic art could emerge from the margins of society, fueled by passion and a deep engagement with the human condition. His work continues to resonate with viewers today because of its emotional immediacy and its vivid portrayal of a specific time and place in Japanese history.

While he may not have founded a school or had a large group of direct followers in the same way as some other artists, his example of uncompromising artistic integrity and his unique expressive style have served as an inspiration. He showed that Japanese artists could fully assimilate and transform Western artistic languages to create something new and deeply personal. His influence can be seen in the broader context of Japanese modern art that values individual expression and emotional intensity.

His life and work serve as a reminder of the often-tenuous existence of artists who operate outside the established systems of patronage and academia. Yet, it is precisely this outsider status that often allows for the creation of art that is challenging, innovative, and profoundly human. Other artists who similarly carved unique paths, such as Zenzaburo Kojima with his distinct modernism, or even earlier individualists like Tomioka Tessai in the Nihonga tradition, highlight the diverse ways Japanese artists have asserted their individuality.

Conclusion: The Unquenchable Fire

Toshiyuki Hasegawa was a meteor in the Japanese art world – brilliant, intense, and tragically short-lived. His paintings are testaments to a life lived with fierce passion and a relentless dedication to his art, despite overwhelming adversity. He captured the soul of early 20th-century Tokyo, its dynamism, its grit, and its people, with an honesty and emotional force that few could match.

His work, characterized by its vibrant, often turbulent colors, its thick, energetic brushwork, and its profound empathy for its subjects, stands as a significant contribution to modern Japanese art. Hasegawa's paintings are not merely historical documents; they are living expressions of a human spirit that, despite being battered by hardship, continued to burn with an unquenchable artistic fire. He remains a vital and compelling figure, an artist whose raw, unfiltered vision continues to captivate and move audiences, solidifying his place as a master of Japanese modernism.