Stefano di Giovanni, more famously known by his posthumously attributed nickname Sassetta (circa 1392 – 1450/1451), stands as one of the most enchanting and pivotal figures of the Sienese School during the early Italian Renaissance. His art forms a delicate yet profound bridge between the lingering elegance of the International Gothic style and the nascent humanism and naturalism of the Renaissance. Active primarily in Siena, with documented work in other Tuscan towns, Sassetta developed a highly personal style characterized by luminous color, graceful linearity, and a deep spiritual intensity that resonated with the devotional needs of his patrons and the unique artistic traditions of his city.

The Enigma of Origins and Early Development

The precise details of Sassetta's birth and early training remain somewhat shrouded in the mists of time, a common challenge for art historians studying artists of this period. He is generally believed to have been born around 1392, though whether in Siena itself or in Cortona, a Tuscan town with its own artistic vibrancy, is a subject of ongoing scholarly discussion. The name "Sassetta" itself is not contemporary but was assigned to him much later by commentators, and its origin is uncertain. His documented name is Stefano di Giovanni di Consolo.

Regardless of his exact birthplace, Siena was undoubtedly the crucible of his artistic formation. The city, a powerful and wealthy republic, boasted a rich artistic heritage distinct from that of its rival, Florence. Sienese painting, exemplified by masters like Duccio di Buoninsegna, Simone Martini, and the brothers Pietro and Ambrogio Lorenzetti in the 14th century, emphasized lyrical beauty, decorative richness, intricate patterns, and a profound, often mystical, spirituality. This tradition, with its emphasis on elegant lines and radiant color, would form the bedrock of Sassetta's art.

While direct documentation is scarce, it is speculated that Sassetta may have received some training in a workshop environment alongside artists such as Benedetto di Bindo or Gregorio di Cecco. Benedetto di Bindo, known for his work on the frescoes in the sacristy of Siena Cathedral, was a significant figure in the Sienese art scene of the early 15th century. Gregorio di Cecco, another Sienese painter, also worked in a style that carried forward the traditions of the Trecento. However, Sassetta's mature style, while rooted in Sienese aesthetics, soon demonstrated a unique sensibility and an openness to external influences that set him apart.

The Confluence of Styles: Gothic Grace and Renaissance Innovation

Sassetta's artistic genius lies in his remarkable ability to synthesize the decorative elegance and spiritual intensity of the Sienese Gothic tradition with the burgeoning interest in naturalism, perspective, and human emotion that characterized the Florentine Renaissance. His figures often possess an elongated, ethereal grace reminiscent of International Gothic art, yet they are imbued with a psychological depth and placed within spatial settings that show an awareness of contemporary Florentine developments.

His palette is a hallmark of his style: clear, luminous, and often employing delicate pastel shades alongside rich, jewel-like tones. Gold backgrounds, a staple of medieval and Gothic art, are frequently used, but Sassetta often combines them with attempts at creating believable, if sometimes intuitively rendered, spatial environments. He demonstrated a sophisticated understanding of light, not perhaps with the scientific rigor of some Florentines, but with an intuitive grasp of how it could model form and create atmosphere. This innovative handling of light and shadow, and his attempts at conveying depth, suggest an engagement with the work of Florentine pioneers.

Indeed, scholars widely acknowledge the influence of Florentine artists on Sassetta. Figures like Masaccio, whose revolutionary frescoes in the Brancacci Chapel in Florence introduced a new level of realism and volumetric solidity, and Fra Angelico, whose art combined profound piety with a sophisticated use of light and color, are often cited as important, if perhaps indirect, influences. Sassetta would have had opportunities to encounter Florentine art through visits or through the movement of artworks and artists. He also seems to have been aware of the work of Gentile da Fabriano, a master of the International Gothic style who worked in Florence and other Italian centers, known for his exquisite detail and courtly elegance, and Masolino da Panicale, who collaborated with Masaccio and also worked in a more graceful, transitional style.

Key Themes and Narrative Power

The vast majority of Sassetta's surviving work is religious in nature, comprising altarpieces, devotional panels, and narrative scenes from the lives of saints. This focus reflects the primary role of art in 15th-century Italy as a vehicle for religious instruction, devotion, and civic pride. Sassetta excelled in conveying the emotional and spiritual core of his subjects. His narratives are often imbued with a gentle pathos or a quiet intensity, avoiding overt melodrama but effectively communicating the significance of the depicted events.

His works reveal a profound contemplation of themes such as divine grace, saintly virtue, the miraculous, and, as noted in some analyses, the interplay of justice, violence, sin, and its consequences. He was particularly adept at creating multi-panel altarpieces (polyptychs) where individual scenes contributed to a larger theological program. These complex works required not only artistic skill but also a keen intellect capable of translating complex religious narratives into compelling visual terms.

Masterpieces and Major Commissions

Sassetta's oeuvre, though not as extensive in its survival as some of his contemporaries, includes several masterpieces that secure his place in the pantheon of early Renaissance artists.

The Arte della Lana Altarpiece (Wool Guild Altarpiece)

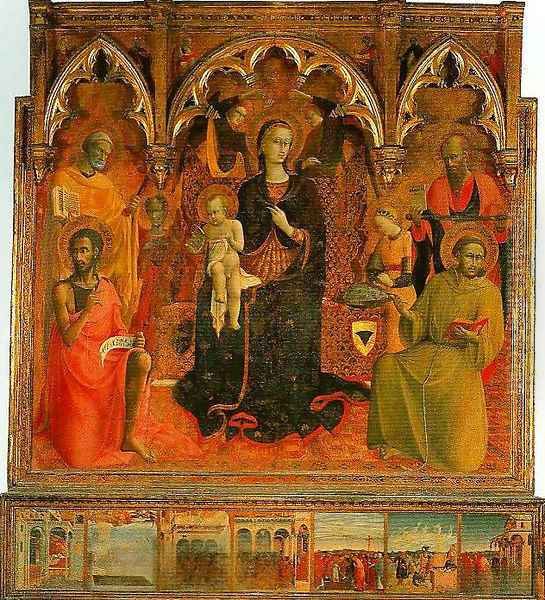

Dated between 1423 and 1426, this was an early and significant commission for the Sienese Wool Merchants' Guild. Originally a complex polyptych, it is now dismembered, with its panels scattered across various museums and private collections worldwide, including the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Siena. The central panel likely depicted the Glorification of the Eucharist, surrounded by saints and narrative scenes. The surviving fragments showcase Sassetta's early mastery of delicate figuration, luminous color, and his emerging ability to organize complex compositions. This work already hints at his distinctive blend of Sienese tradition and an awakening interest in more naturalistic representation.

The Madonna of the Snow (Pala della Neve)

Commissioned in 1430 and completed by 1432 for the altar of Saint Boniface in Siena Cathedral, this is arguably one of Sassetta's most celebrated and innovative works. Now housed in the Palazzo Pitti, Florence (Contini Bonacossi Collection), the altarpiece depicts the miraculous founding of the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome, where snow fell in August, outlining the church's plan. The central panel shows the Virgin and Child enthroned, flanked by saints, with angels gracefully hovering. What makes this work particularly remarkable is its sophisticated spatial construction, especially in the predella panels which narrate the story of the miraculous snowfall. Sassetta creates a sense of depth and atmosphere that was advanced for Sienese painting of the time. The architectural elements are rendered with a keen eye for perspective, and the figures interact within these spaces in a convincing manner. Recent technical analysis has also revealed Sassetta's close collaboration with the carpenter who constructed the elaborate frame, suggesting a holistic approach to the altarpiece as an immersive devotional object. The attribution of this work to Sassetta, while once debated by some, is now widely accepted by scholars.

The Borgo San Sepolcro Altarpiece (Polyptych of Saint Francis)

This monumental double-sided altarpiece, created between 1437 and 1444 for the high altar of the church of San Francesco in Borgo San Sepolcro (now Sansepolcro), was another major undertaking. Like the Arte della Lana altarpiece, it has been dismembered, and its panels are now in various collections, including the National Gallery, London (which holds St. Francis in Ecstasy and scenes from his life like The Mystic Marriage of St. Francis with Poverty), the Louvre in Paris, and the Villa I Tatti (Berenson Collection) in Florence, which houses the stunning Funeral of St. Francis and the Verification of the Stigmata. This latter panel is a masterpiece of narrative composition and emotional expression, depicting the mourners around the saint's bier with a poignant realism. The altarpiece as a whole celebrated the life and virtues of Saint Francis of Assisi, a theme particularly resonant with the Franciscan order. Sassetta's depiction of St. Francis combines iconic reverence with a sense of human accessibility, drawing on the rich visual tradition established by earlier artists like Giotto di Bondone in his famous Assisi frescoes.

Other Notable Works

Other significant works attributed to Sassetta include The Miracle of the Holy Sacrament (or A Miracle of the Eucharist), a predella panel known for its dramatic narrative and exploration of themes of justice and divine intervention. Various Madonna and Child compositions, such as the Madonna of Humility, showcase his ability to convey tender intimacy and serene devotion. The Madonna of Humility has itself been the subject of restoration discussions, highlighting the challenges and occasional controversies involved in preserving and presenting early panel paintings to modern audiences. Panels depicting scenes from the Legend of St. Anthony Abbot are notable for their vivid storytelling and almost fantastical landscapes, further underscoring Sassetta's narrative gifts.

Theatricality and Narrative Innovation

A distinctive feature of Sassetta's art, particularly noted in works like the St. Anthony Abbot series, is its inherent theatricality. Siena had a vibrant tradition of religious drama and pageantry, and it is plausible that these public performances influenced Sassetta's approach to visual storytelling. His compositions often have a stage-like quality, with figures arranged in expressive groupings and gestures that convey the unfolding drama. He was skilled at breaking down a narrative into key moments, each rendered with clarity and emotional impact. This ability to create compelling visual narratives, often with a touch of mystical wonder, was highly valued and contributed significantly to his reputation.

Workshop, Collaborators, and Influence on Later Artists

Like most successful artists of his time, Sassetta would have maintained a workshop to assist with the execution of large commissions. While the identities of all his assistants are not known, his style had a discernible impact on the next generation of Sienese painters.

His most notable follower was Sano di Pietro, who adopted many aspects of Sassetta's graceful style, albeit often with a slightly sweeter and less intellectually rigorous sensibility. Sano di Pietro became one of the most prolific Sienese painters of the mid-15th century, and his work helped to perpetuate Sassetta's influence.

Other Sienese artists active during or shortly after Sassetta's time, such as Giovanni di Paolo, developed their own highly individualistic styles, but the broader Sienese artistic environment was undoubtedly shaped by Sassetta's achievements. Giovanni di Paolo, for instance, while known for his more eccentric and visionary interpretations, shared with Sassetta a commitment to expressive line and vibrant color. The so-called "Griselda Master," an anonymous Sienese painter active in the late 15th century, has sometimes been linked to Sassetta in discussions of attribution, though this artist's style is generally considered distinct and later.

While direct collaborative projects with major Florentine artists like Masaccio or Fra Angelico are not documented, Sassetta's absorption of their innovations demonstrates an active engagement with the broader Italian artistic landscape. His influence, though primarily felt in Siena and Tuscany, contributed to the rich tapestry of Italian Renaissance art. He showed how Sienese art could evolve and incorporate new ideas without entirely abandoning its unique heritage. His approach to landscape, often imbued with a lyrical quality, and his sensitive portrayal of figures, found echoes in the work of later artists. Even artists working in different centers, like the Umbrian painter Piero della Francesca (who also worked in Borgo San Sepolcro and whose rigorous perspectival constructions offer a fascinating contrast to Sassetta's more intuitive approach), would have been aware of the artistic currents Sassetta represented.

Later Career, Death, and Posthumous Reputation

Sassetta continued to be a leading figure in Sienese art throughout his career. His final major commission was for the fresco decoration of the Porta Romana, one of Siena's city gates. This was a prestigious project, indicative of his high standing. Unfortunately, he contracted an illness, possibly pneumonia, while working on these frescoes exposed to the elements, and he died in 1450 or 1451 before their completion. The work was later finished by Sano di Pietro.

For a period after his death, Sassetta's reputation remained high. However, as artistic tastes shifted in the High Renaissance and beyond, with a greater emphasis on the monumental classicism of Rome and the continued innovations of Florence, the more delicate and spiritually infused art of Siena, including Sassetta's, gradually fell into relative obscurity. Artists like Raphael and Michelangelo came to define the pinnacle of Renaissance achievement for later generations.

It was not until the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with the pioneering work of art historians and connoisseurs like Bernard Berenson, that Sassetta and other early Italian masters were "rediscovered" and their unique contributions re-evaluated. Berenson, in particular, championed Sassetta for his exquisite craftsmanship, his poetic sensibility, and his importance as a transitional figure. This reassessment led to a renewed appreciation for Sienese art in general and for Sassetta's specific achievements.

Restoration, Attribution, and Scholarly Debates

The study of Sassetta's work is an ongoing process, involving technical analysis, archival research, and connoisseurship. The restoration of his paintings, such as the aforementioned Madonna of Humility, can sometimes spark debate among experts regarding the extent of intervention and the preservation of the artist's original intent. These are complex issues, as conservators must balance the need to stabilize fragile artworks with the desire to present them in a visually coherent manner, often removing layers of later overpaint or discolored varnish.

Attribution also remains a key area of scholarly focus. Distinguishing Sassetta's hand from that of his workshop assistants or contemporary imitators can be challenging, especially for smaller panels or works that have suffered damage over time. The debate concerning the "Griselda Master" and his relationship, if any, to Sassetta's circle illustrates the complexities of attributing works from this period. Furthermore, the dismemberment of many of his large altarpieces means that reconstructing their original appearance and understanding their full iconographic programs requires meticulous research and often involves international collaboration among museums. The historical context of these works, including the challenges of environmental imbalances over centuries, also impacts their current state and the approaches taken for their conservation.

It is important to note that Sassetta was not active in the court of Urbino. The artistic flourishing of Urbino under Duke Federico da Montefeltro (ruled 1444-1482) involved artists like Piero della Francesca, the Fleming Justus van Ghent, the Spaniard Pedro Berruguete, and later, Giovanni Santi (Raphael's father) and Timoteo Viti. Sassetta's career was firmly rooted in the Sienese sphere.

Conclusion: Sassetta's Enduring Legacy

Stefano di Giovanni Sassetta remains a captivating figure in the history of Italian art. He was an artist of profound sensitivity and technical brilliance who navigated the artistic currents of his time with remarkable skill and originality. He successfully melded the decorative elegance and spiritual depth of the Sienese Gothic tradition with the new Renaissance interest in naturalism, perspective, and human emotion, creating a style that was uniquely his own. His luminous colors, graceful figures, and compelling narratives continue to enchant viewers today.

His major altarpieces, such as the Madonna of the Snow and the Borgo San Sepolcro polyptych, stand as testaments to his ambition and his ability to manage large-scale, complex commissions. Through his work, and his influence on followers like Sano di Pietro, Sassetta played a crucial role in the evolution of Sienese painting in the 15th century, ensuring that Siena remained a vital artistic center even as Florence rose to prominence. The renewed appreciation for his art in modern times has rightfully restored him to his place as one of the last great masters of the Sienese school and a significant contributor to the broader story of the Italian Renaissance. His art serves as a poignant reminder of the rich diversity of regional styles that characterized this transformative period in European culture.