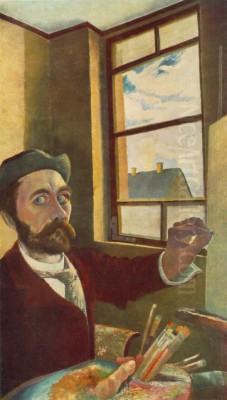

Tivadar Kosztka Csontváry stands as one of Hungarian art history's most enigmatic and compelling figures. A pharmacist by trade who turned to painting relatively late in life, driven by a profound, almost mystical calling, Csontváry (1853-1919) created a body of work that remains unique in its vision, scale, and spiritual intensity. His art, often characterized by vibrant, luminous colors and monumental landscapes, defies easy categorization, blending elements of Post-Impressionism, Expressionism, and Symbolism, yet always remaining distinctly his own. Though largely misunderstood and unappreciated during his lifetime in his native Hungary, his genius was recognized by some in Europe and has been increasingly celebrated posthumously, securing his place as a pivotal, if solitary, pioneer of modern art.

Early Life and the Prophetic Call

Born Mihály Tivadar Kosztka on July 5, 1853, in Kisszeben, Sáros County, in the Kingdom of Hungary (now Sabinov, Slovakia), his family had Polish roots. His father, Dr. László Kosztka, was a physician and pharmacist, and young Tivadar initially followed a more conventional path. He worked as a pharmacist for over a decade, a profession that provided him with a degree of financial stability but seemingly little artistic fulfillment. His early life gave few indications of the extraordinary artistic journey that lay ahead.

The pivotal moment in Csontváry's life occurred in 1880, at the age of 27. According to his autobiographical writings, while sketching a scene on a prescription pad – an ox cart passing by – he heard a voice or had a profound internal conviction that he was destined to become "the greatest plein air painter in the world, greater than Raphael." This revelatory experience was not a fleeting fancy; it became the guiding force of his existence, compelling him to abandon his pharmaceutical career and dedicate himself entirely to art. This sense of a divine mission, or at least a destiny of unparalleled artistic achievement, would fuel his relentless pursuit of a unique visual language.

The Path to Artistic Realization: Travels and Studies

Following his epiphany, Csontváry did not immediately plunge into full-time painting. He methodically prepared, first ensuring financial independence by leasing out his pharmacy. Then, in the 1890s, he embarked on a series of journeys to study art. He traveled to Rome, where he undoubtedly encountered the works of the Renaissance masters, including the very Raphael he aimed to surpass. He later studied in Munich with Simon Hollósy, a prominent Hungarian painter and influential teacher who founded the Nagybánya artists' colony, a significant movement in Hungarian art that embraced plein air painting and naturalism.

Csontváry also spent time in Karlsruhe, learning from Friedrich Kallmorgen, and later in Paris at the Académie Julian, a popular destination for international artists. In Paris, he would have been exposed to the ferment of Post-Impressionist and Symbolist ideas. While he admired the work of the renowned Hungarian realist Mihály Munkácsy, whose dramatic compositions and international fame were significant, Csontváry’s own artistic inclinations were leading him down a far more individualistic and visionary path than Munkácsy’s or even the naturalism of the Nagybánya school, whose members included Károly Ferenczy and Béla Iványi-Grünwald.

His travels were not confined to European art centers. Driven by an insatiable curiosity and a desire to capture the essence of diverse landscapes and ancient cultures, Csontváry journeyed extensively through Italy, Greece, Dalmatia, Palestine, Egypt, Syria, and Lebanon. These expeditions were not mere tourist trips; they were artistic pilgrimages. He sought out sites of historical and spiritual significance, dramatic natural phenomena, and landscapes bathed in intense, otherworldly light. These experiences profoundly shaped his subject matter and his distinctive palette.

Artistic Style: A Fusion of Vision and Technique

Csontváry's style is difficult to pigeonhole. While he absorbed influences from various movements, his work ultimately stands apart. He is often associated with Post-Impressionism due to his expressive use of color and departure from purely representational art, sharing a certain intensity with figures like Vincent van Gogh, though their thematic concerns and stylistic execution differed significantly. His emphasis on emotional content and subjective experience also aligns him with Expressionism, predating or running parallel to early Expressionists like Edvard Munch.

A strong element of Symbolism pervades his canvases. His landscapes are rarely just depictions of place; they are imbued with deeper meanings, often exploring themes of solitude, eternity, the power of nature, and spiritual transcendence. In this, he shares a kinship with Symbolist painters like Gustave Moreau or Odilon Redon, who sought to convey ideas and emotions beyond the visible world, though Csontváry’s symbolism was often more personal and less tied to established mythological or literary sources.

One of the most striking aspects of Csontváry's art is his use of color. He employed a palette of extraordinary vibrancy and luminosity, often featuring brilliant blues, radiant yellows, deep oranges, and intense greens. His colors are not merely descriptive but are charged with emotional and symbolic power, creating an almost hallucinatory effect in some works. He developed what he called "solar path" (napút) painting, an attempt to capture the full spectrum of sunlight and its transformative effects on the landscape. This sometimes involved a technique that has been described as a "double perspective," allowing him to depict scenes with an expansive, almost panoramic scope and an unusual clarity of light and shadow.

His brushwork could vary from meticulous detail to broader, more expressive strokes, depending on the subject and the desired effect. He often worked on a monumental scale, creating vast canvases that envelop the viewer, enhancing the immersive quality of his visionary landscapes. This preference for large formats further distinguishes him from many of his contemporaries.

Major Works: Monuments of a Singular Vision

Csontváry's oeuvre, though not vast in number (around one hundred paintings), contains several masterpieces that secure his legacy.

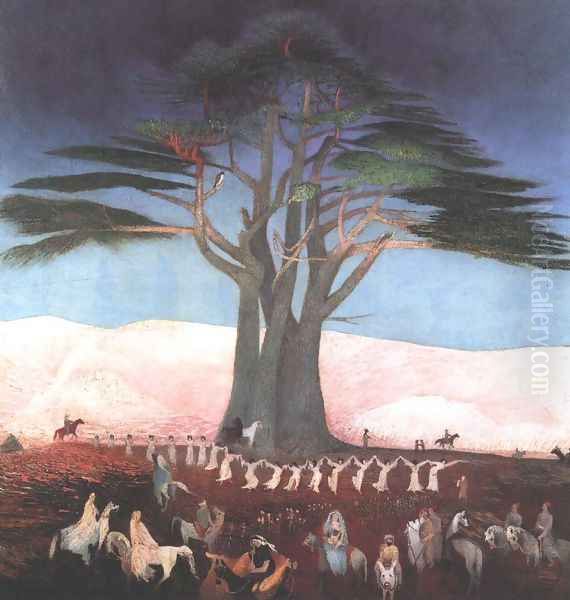

The Lonely Cedar (A magányos cédrus) (1907): Perhaps his most iconic painting, this work depicts a solitary, ancient cedar tree set against a dramatic, luminous sky. The tree, a recurring motif in his work, symbolizes resilience, solitude, and eternity. Its gnarled branches reach towards a sky filled with an almost supernatural light. The vibrant, almost electric colors and the monumental presence of the cedar create an image of profound spiritual power. It is often compared in its emotional impact to the solitary figures or trees in the work of Caspar David Friedrich, though Csontváry's palette is far more intense.

Pilgrimage to the Cedars in Lebanon (Zarándoklás a cédrusokhoz Libanonban) (1907): Related to The Lonely Cedar, this large-scale painting shows a procession of figures approaching a grove of ancient cedar trees, again under a sky of extraordinary color. The work evokes a sense of sacred journey and communion with nature's enduring majesty. The scale and ambition are reminiscent of grand historical or religious paintings, yet the focus is on a personal, spiritual encounter with the natural world.

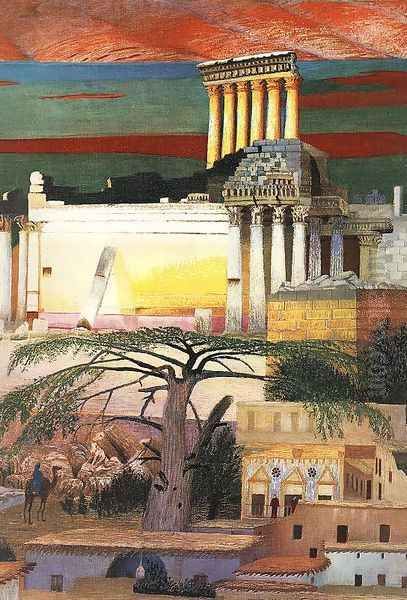

Baalbek (1906): This monumental canvas, one of his largest, depicts the colossal Roman ruins at Baalbek in Lebanon. Csontváry masterfully captures the grandeur of the ancient architecture and the intense light of the Middle Eastern sun. The painting is not just an archaeological record but a meditation on the passage of time, the rise and fall of civilizations, and the enduring power of human creation set against the vastness of nature. The meticulous detail combined with the atmospheric light showcases his unique technical abilities.

Ruins of the Greek Theatre at Taormina (A taorminai görög színház romjai) (1904-1905): Another vast panorama, this painting presents the ancient Greek theatre in Sicily with Mount Etna smoking in the background. The interplay of light and shadow, the vibrant colors of the Mediterranean landscape, and the historical resonance of the site are all hallmarks of Csontváry's vision. The painting is celebrated for its complex composition and the way it captures a specific moment in time, with the sun setting and casting long shadows. Some critics have noted a fascinating duality in this painting; if a mirror is placed in the center, one side can be interpreted as representing God and creation, the other, perhaps, a more somber or even demonic aspect, reflecting Csontváry's complex worldview.

Mary's Well at Nazareth (Mária kútja Názáretben) (1908): This painting depicts a biblical scene with a characteristically vibrant palette and a focus on the spiritual atmosphere of the Holy Land. The figures are somewhat stylized, and the emphasis is on the sacredness of the location and the intensity of the light.

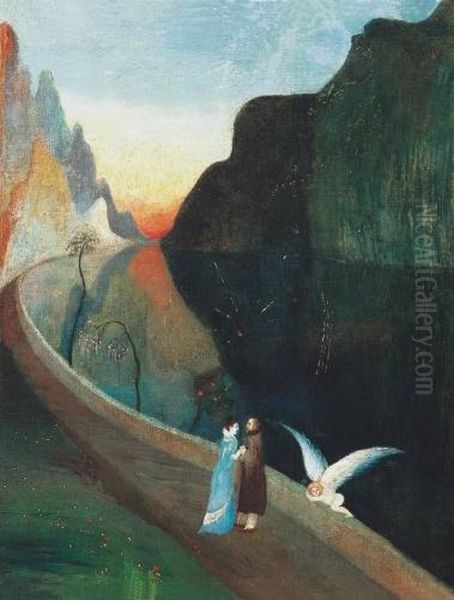

Rendezvous of Lovers (Szerelmesek találkozása) (c. 1902): An earlier, more intimate work, this painting shows a couple meeting in a moonlit landscape. It has a dreamlike, romantic quality, with the figures almost blending into the mystical atmosphere created by the soft light and rich colors. It hints at the Symbolist tendencies that would become more pronounced in his later, larger works.

These works, among others, demonstrate Csontváry's ambition to create an art that was both visually stunning and spiritually profound, an art that could transport the viewer to other realms, whether geographical or metaphysical.

Reception: Misunderstanding and Posthumous Acclaim

During his lifetime, Csontváry's art met with a mixed, and often negative, reception in Hungary. His unconventional style, his grandiose claims about his artistic destiny (fueled by the 1880 prophecy), and his increasingly eccentric personality led many in the conservative Hungarian art establishment to dismiss him as a dilettante or even as mentally unstable. He was often referred to as the "mad painter." His exhibitions in Budapest, such as one in 1908, were largely met with incomprehension or ridicule. The prevailing artistic tastes in Hungary at the time often favored more academic or established Impressionist styles, such as those of Pál Szinyei Merse, or the aforementioned naturalism of the Nagybánya school. Csontváry’s visionary intensity and highly personal symbolism found little purchase.

However, he did achieve some recognition abroad. An exhibition of his works in Paris in 1907 garnered positive attention, and it is reported that Pablo Picasso, upon seeing his work later, remarked, "I did not know that there was another great painter in our century besides myself." While the veracity of this specific quote is debated, it reflects the kind of impact his work could have on artists open to new forms of expression.

Despite this occasional international encouragement, the lack of sustained recognition, particularly in his homeland, took its toll. Around 1909, Csontváry largely ceased painting. His creative energies shifted towards writing pamphlets and philosophical treatises on topics such as pacifism, vegetarianism, the genius of the Hungarian nation, and his own artistic theories. His mental health, which had always seemed fragile, deteriorated further. He suffered from periods of paranoia and was diagnosed with what might today be considered schizophrenia or a related condition.

Csontváry died in Budapest on June 20, 1919, in relative obscurity and poverty. His artistic legacy was precarious. After his death, his vast canvases were reportedly offered to cab drivers to be used as tarpaulins. It was only through the timely intervention of a young architect, Gedeon Gerlóczy, who recognized their value and purchased them, that Csontváry's major works were saved from destruction.

The process of Csontváry's rediscovery was gradual. Exhibitions in the 1930s began to shed new light on his work. However, it was not until after World War II, particularly with major retrospective exhibitions in Székesfehérvár (1963) and Budapest (at the Hungarian National Gallery), that his status as a major figure in Hungarian and, indeed, European art began to be firmly established. His work was seen to resonate with later artistic developments, including Surrealism, due to its dreamlike qualities and exploration of the subconscious, even though he was not directly part of the Surrealist movement led by figures like André Breton or Salvador Dalí. His unique vision also found parallels with so-called "outsider artists" or naïve painters like Henri Rousseau, who also created fantastical worlds born of intense personal vision.

The Enigmatic Personality and Solitary Path

Csontváry's life and art are inextricably linked to his unique personality. His unwavering belief in his artistic mission, bordering on messianic conviction, set him apart from his contemporaries. He was a solitary figure, not part of any artistic group or movement. While he studied with established painters, he quickly forged his own path, driven by internal imperatives rather than external trends.

His vegetarianism, his pacifist writings, and his often eccentric behavior contributed to his image as an outsider. This isolation was likely both a source of strength, allowing him to develop his singular vision unhindered, and a source of profound frustration, given his craving for recognition as the great painter he believed himself to be. His mental health struggles undoubtedly played a role in both his creative output and his social interactions. Some scholars argue that his psychological state directly informed the visionary, sometimes unsettling, quality of his art.

The sheer ambition of his projects, the immense scale of his canvases, and the arduous journeys he undertook to find his subjects speak to an extraordinary determination and a singular focus. He was not content to paint the familiar landscapes of Hungary; he sought out the epic, the ancient, and the sublime, from the cedars of Lebanon to the ruins of Taormina. This global perspective was unusual for artists of his time and place.

Interactions with Contemporaries: A Limited Engagement

Given his solitary nature and unique artistic trajectory, Csontváry's direct interactions with contemporary artists appear to have been limited, especially in terms of collaborative relationships or deep artistic dialogues. While he studied under figures like Simon Hollósy, his path diverged significantly from the Nagybánya artists' collective approach. He admired Mihály Munkácsy, but Munkácsy represented an older generation and a different artistic tradition.

There is little evidence of sustained correspondence or close friendships with other major European artists of his time, such as the leading French Post-Impressionists Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin, or Georges Seurat, or the burgeoning Expressionists in Germany or Austria like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner or Egon Schiele. His travels were primarily for his own artistic research rather than for integrating into international artistic circles.

In Hungary, he was more an object of curiosity or even derision than a peer to be engaged with. Artists like József Rippl-Rónai, who successfully integrated French Post-Impressionist and Art Nouveau influences into a Hungarian context, operated within a different sphere. Lajos Gulácsy, another highly individualistic and somewhat melancholic Hungarian painter of the era, shared a certain poetic and imaginative sensibility with Csontváry, and some art historians have noted a "mysterious connection" or spiritual kinship between them, though direct collaboration is not documented. Sándor Molnár, a later artist, reportedly felt Csontváry was one of the modern Hungarian artists closest to his own thinking, but this is a posthumous reflection of influence rather than contemporary interaction.

His legacy, therefore, is not one built through a network of artistic exchange in the way that, for example, the Impressionists influenced each other, or the Cubists Picasso and Georges Braque collaborated. Csontváry's influence was more delayed, a slow burn that ignited fully only after his work was rediscovered and re-evaluated by later generations.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Today, Tivadar Kosztka Csontváry is recognized as a giant of Hungarian art and a significant, if idiosyncratic, figure in the broader European modern art landscape. The Csontváry Museum in Pécs, Hungary, established in 1973, houses many of his most important works and stands as a testament to his enduring importance. His paintings are prized possessions of the Hungarian National Gallery in Budapest.

His art continues to fascinate for its unique blend of meticulous realism and visionary fantasy, its breathtaking scale, and its incandescent color. He is seen as a forerunner of several artistic trends, a painter who, working in relative isolation, anticipated aspects of Expressionism and Surrealism. His deep spiritual connection to nature and his exploration of universal themes of existence, time, and transcendence give his work a timeless quality.

Csontváry's life story, with its dramatic call to art, its struggles, and its ultimate, posthumous triumph, adds to his legend. He embodies the archetype of the misunderstood genius, the visionary artist whose work was too radical or too personal for his own time but found its audience with posterity. His influence can be seen in later Hungarian artists who have valued expressive color, monumental composition, and a deeply personal artistic vision.

His paintings command high prices at auction when they rarely appear, reflecting his established international reputation. More importantly, they continue to inspire awe and wonder, inviting viewers into a world shaped by an extraordinary imagination and an unwavering commitment to a singular artistic quest. Tivadar Kosztka Csontváry remains a testament to the power of individual vision to transcend convention and create an art that speaks across generations. His solitary path led to a unique artistic peak, a vibrant, sun-drenched world that continues to illuminate the landscape of art history.