Oscar Edmund Berninghaus stands as a pivotal figure in the landscape of American art, particularly renowned for his evocative portrayals of the American Southwest. Born in the bustling city of St. Louis, Missouri, on October 2, 1874, his life journey would lead him far from his Midwestern roots to the unique cultural and geographical tapestry of Taos, New Mexico. His contributions as a founding member of the influential Taos Society of Artists cemented his legacy, ensuring his work remains a significant touchstone in the narrative of early 20th-century American painting. Berninghaus passed away in his beloved Taos on April 27, 1952, leaving behind a rich body of work that continues to captivate audiences with its authenticity and artistic brilliance.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in St. Louis

Berninghaus's artistic inclinations surfaced early in his life. Growing up in St. Louis, a major hub of commerce and culture on the Mississippi River, he was exposed to the world of commercial art through his family's involvement in a lithography business. This environment provided a practical, albeit informal, introduction to the visual arts and printing techniques. Formal schooling held less appeal for the young Berninghaus than the call of art and the world of work.

At the age of sixteen, driven by a desire to pursue art more seriously and support himself, Berninghaus left school. He found employment in a local printing house, immersing himself in the technical crafts of lithography and engraving. This hands-on experience proved invaluable, grounding his artistic development in solid draftsmanship and an understanding of reproductive processes. However, he recognized the need for formal training to refine his burgeoning talent.

To supplement his practical skills, Berninghaus enrolled in night classes at the St. Louis School of Fine Arts, which was then affiliated with Washington University. This allowed him to continue working during the day while dedicating his evenings to drawing, painting, and composition under academic guidance. Even in these early stages, his talent was evident, and he began earning modest sums by selling sketches and watercolors, demonstrating an early fusion of artistic passion and commercial acumen that would characterize much of his career. His St. Louis years laid the essential foundation for his future success.

The Transformative Journey West

The year 1899 marked a crucial turning point in Berninghaus's life and artistic trajectory. He received a commission from the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad, a company eager to promote tourism to the scenic landscapes accessible via its routes. His task was to travel through Colorado and New Mexico, creating sketches and illustrations for the railroad's promotional literature. This assignment was more than just a job; it was an expedition into a world vastly different from the urban environment of St. Louis.

Traveling by rail and stagecoach, Berninghaus ventured into the heart of the American Southwest. The dramatic landscapes, the intense clarity of the light, the vibrant cultures of the Native American and Hispanic communities – all made an indelible impression on him. His journey eventually led him to the small, relatively isolated village of Taos, nestled in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains of northern New Mexico.

His arrival in Taos was serendipitous. He was immediately captivated by the picturesque adobe architecture, the stunning mountain backdrop, and, most importantly, the Pueblo Indians whose ancient culture permeated the region. The unique atmosphere and visual richness of Taos resonated deeply with his artistic sensibilities. Although his initial stay was brief – reportedly cut short by a bout of illness sometimes referred to as the "Taos germ" – the experience was profound. He knew he had found a subject matter that would engage him for a lifetime.

Balancing Two Worlds: St. Louis and Taos

Following his initial transformative visit in 1899, Berninghaus returned to his established life and commercial art career in St. Louis. However, the magnetic pull of Taos was undeniable. For the next quarter-century, he developed a pattern that balanced his professional obligations in Missouri with his artistic passion for New Mexico. He would spend the winter months in St. Louis, fulfilling commercial illustration commissions and maintaining his connections there.

These commercial projects, while perhaps less artistically fulfilling than his fine art pursuits, provided financial stability and honed his skills in narrative composition and clear visual communication. His work appeared in popular publications and advertisements, including notable campaigns for Anheuser-Busch Brewing Association, showcasing his versatility and reliability as a commercial artist. This practical experience likely influenced his fine art, contributing to the strong sense of design and narrative clarity often found in his paintings.

Come summer, however, Berninghaus would pack his bags and make the long journey back to Taos. These annual summer sojourns became essential periods of artistic immersion and renewal. He would spend months sketching and painting en plein air, capturing the unique light, landscapes, and people of the region. He interacted with the local Pueblo Indians, gaining their trust and developing a deep respect for their way of life, which he sought to portray with dignity and accuracy. This dual existence continued until 1925, when the allure of Taos finally proved irresistible, prompting him to make it his permanent home.

The Genesis of the Taos Society of Artists

During his summer visits, Berninghaus connected with other artists who, like him, had been drawn to the unique character of Taos. By the early 1910s, a small but dedicated group of painters recognized the potential of Taos not just as a source of inspiration but as a center for a distinctly American art movement focused on the Southwest. They shared a common goal: to capture the essence of the region and its people and to bring their work to a national audience.

In July 1915, this shared vision culminated in the formal establishment of the Taos Society of Artists (TSA). Oscar E. Berninghaus was one of the six founding members, alongside Ernest L. Blumenschein, Joseph Henry Sharp, E. Irving Couse, W. Herbert "Buck" Dunton, and Bert Geer Phillips. These artists formed the core of the group, united by their commitment to depicting Southwestern themes and their desire for collective promotion.

The TSA was more than just a social club; it was a strategic professional organization. Its primary aim was to organize traveling exhibitions of its members' work, sending curated shows to major cities across the United States, particularly in the East and Midwest. This collective marketing effort helped overcome the challenges of their remote location, bringing national attention to Taos and establishing the reputations of its member artists. Berninghaus played an active role in the Society, contributing works to its exhibitions and participating in its governance, solidifying his position as a key figure in this influential art colony. Other notable artists like Walter Ufer and Victor Higgins would later join the TSA, further strengthening its impact.

Life and Work in Taos

Making Taos his year-round residence in 1925 marked the final commitment in Berninghaus's long relationship with the region. Settling permanently allowed him to fully immerse himself in the community and dedicate himself more completely to his fine art. He established a home and studio, becoming an integral part of the fabric of the growing Taos art colony.

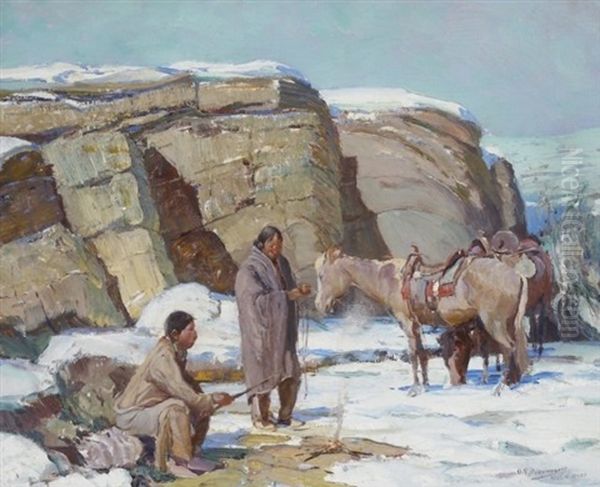

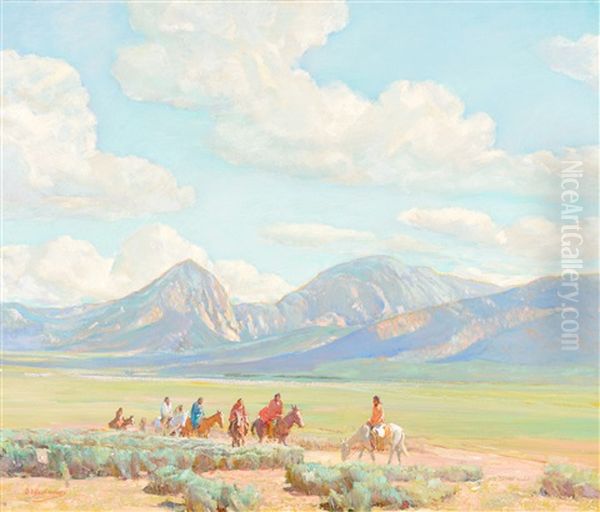

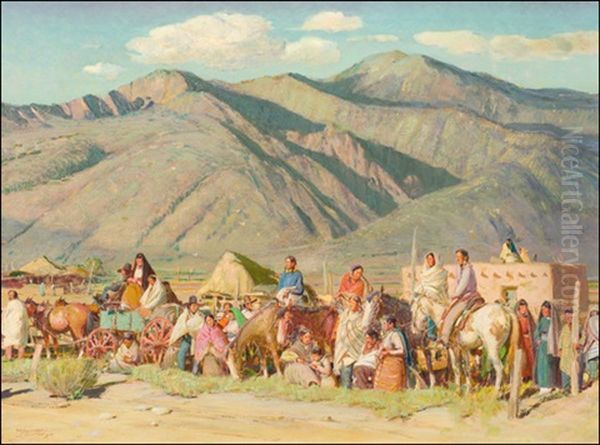

Life in Taos provided constant inspiration. The changing seasons brought different qualities of light and color to the landscape, from the snow-covered adobes in winter to the vibrant wildflowers of summer. The daily lives and ceremonial practices of the Taos Pueblo Indians offered rich subject matter, which Berninghaus approached with sensitivity and a desire for authenticity. He often depicted scenes of Native Americans on horseback against the dramatic backdrop of the mountains, capturing moments of quiet dignity or communal activity.

His studio became a space for translating the sketches and impressions gathered outdoors into finished canvases. While he embraced plein air painting for capturing immediate effects, much of his larger, more complex work was completed in the studio. Contemporaries noted his remarkable visual memory; later in his career, he was said to be able to paint figures and horses accurately without direct reference, relying on years of close observation. His presence contributed significantly to the creative energy of Taos, which also attracted artists like Nicolai Fechin, Andrew Dasburg, and visitors such as Robert Henri and John Sloan.

Artistic Style: Impressionism Meets the Southwest

Berninghaus's artistic style evolved throughout his career but remained rooted in a foundation of strong draftsmanship and an appreciation for the effects of light and color. His early work, particularly after his initial encounters with Taos, shows clear influences from Impressionism. He employed broken brushwork and a brighter palette to capture the intense, high-altitude light of the Southwest and its effect on the landscape and figures.

Unlike French Impressionists who often focused on fleeting moments and atmospheric effects, Berninghaus combined impressionistic techniques with a strong sense of structure and narrative. His background in illustration likely contributed to his emphasis on clear composition and storytelling. His paintings often feature well-defined figures and animals integrated harmoniously into the landscape, conveying a sense of place and human presence within it.

He was particularly adept at rendering the textures of the Southwest – the rough surfaces of adobe walls, the dusty earth, the hides of horses, the fabrics of traditional clothing. His brushwork, often characterized by short, decisive strokes, built up form and surface effectively. While color and light were paramount, his drawing remained solid, giving his figures and animals a convincing sense of weight and volume. Over time, while retaining a vibrant palette, his forms sometimes became more simplified and monumental, reflecting perhaps a deeper understanding of the enduring spirit of his subjects. His approach differed from the more modernist explorations of artists like Marsden Hartley or Georgia O'Keeffe, who also worked in New Mexico, yet shared a profound connection to the spirit of the place.

Enduring Themes: Landscape, Culture, and History

The subject matter of Oscar E. Berninghaus's art remained consistently focused on the American Southwest throughout his mature career. His works serve as a visual chronicle of northern New Mexico in the first half of the 20th century, capturing its unique blend of cultures and its breathtaking natural environment.

Landscapes were a fundamental element, often serving as more than just a backdrop. The towering Taos Mountain, the vast plains, the winding rivers, and the distinctive adobe architecture feature prominently, rendered with an understanding of the region's specific atmospheric conditions and light. He captured the dramatic shifts in weather and seasons, from sun-drenched summer days to the cool, clear light of winter.

The people of the region were central to his vision. He held a deep admiration for the Pueblo Indians of Taos and Picuris, depicting their daily lives, agricultural practices, horsemanship, and ceremonial gatherings with respect and dignity. While viewed through the lens of his time, his portrayals generally avoided overt sensationalism, aiming for an honest representation of their enduring culture. He also painted scenes featuring the local Hispanic population and occasionally explored themes related to the earlier pioneer history of the West, though his primary focus remained the contemporary Native American life he observed around him. Horses were another favorite subject, rendered with anatomical accuracy and a sense of their vital importance to life in the region.

Representative Works: Capturing the Essence

Several paintings stand out as representative of Berninghaus's style and thematic concerns. A Conference at the Pueblo exemplifies his skill in composing multi-figure scenes within an architectural setting, capturing a moment of quiet discussion among Taos Pueblo men against the backdrop of the iconic multi-storied pueblo structure. The interplay of light and shadow on the adobe walls is masterfully handled.

Taos Indian Rabbit Hunt showcases his ability to depict figures and animals in motion within the landscape. The energy of the hunt, the dynamic poses of the horses and riders, and the expansive sweep of the terrain are rendered with vitality and strong compositional design. It reflects his interest in the traditional activities of the Pueblo people.

Peace and Plenty is often cited as one of his major works. This large canvas presents an idealized, harmonious vision of Pueblo life, featuring figures engaged in various activities amidst symbols of agricultural abundance, set against the majestic Taos Mountain. The painting embodies a sense of tranquility and timeless connection to the land.

Winter in Taos demonstrates his sensitivity to different atmospheric conditions. He effectively captures the cool light and subtle colors of a snow-covered landscape, often featuring figures bundled against the cold or smoke rising from chimneys, conveying the quiet beauty of the season. Other notable works include Their Son, The Apple Orchard, and murals like Gateway to the Frontier, showcasing his versatility across different formats and subjects. These works, among many others, solidify his reputation as a keen observer and skilled interpreter of the Southwest.

Relationships with Contemporaries and the Taos Milieu

Berninghaus was not an isolated artist; he was an active participant in the vibrant artistic community of Taos. His role as a founder of the Taos Society of Artists placed him at the center of collaborative efforts with Blumenschein, Sharp, Couse, Dunton, and Phillips. These men were not just colleagues but often friends, sharing experiences, critiques, and the challenges of building an art market for their Southwestern subjects. They learned from each other, even as each developed a distinct style.

Beyond the initial founders, Berninghaus interacted with later TSA members like Victor Higgins, Walter Ufer, E. Martin Hennings, and Kenneth Adams. Each brought their own perspective, contributing to the diversity within the Taos school. Higgins and Ufer, for instance, often employed a bolder, more modernist-influenced style compared to Berninghaus's more impressionistic realism.

The influence also flowed outwards. The success of the TSA attracted other prominent artists to visit or settle in the region. Figures like Robert Henri, a key figure in the Ashcan School and an influential teacher, visited Taos and encouraged his students, including John Sloan and Stuart Davis, to experience the Southwest. While their styles differed significantly, their presence added to the artistic ferment. Later arrivals like the Russian émigré Nicolai Fechin, known for his expressive portraits and dynamic style, and Andrew Dasburg, who explored more abstract and structural approaches to the landscape, further enriched the Taos art scene, creating an environment of diverse artistic exploration alongside the more traditional representational work of Berninghaus and his TSA colleagues.

Anecdotes and Considerations

While Berninghaus's career was marked by steady professionalism and dedication, a few anecdotes and considerations add texture to his biography. The story of him contracting the "Taos germ" on his first visit is often recounted, highlighting the somewhat rugged conditions of Taos at the turn of the century and the profound impact the place had on him despite the initial discomfort.

His ability to maintain a successful commercial art career in St. Louis for over two decades while simultaneously developing his fine art practice focused on Taos speaks to his discipline and pragmatism. This dual path sometimes led to discussions about the relationship between illustration and fine art in his work, though he successfully navigated both worlds.

A significant consideration in evaluating Berninghaus's work today involves the representation of Native American subjects. While he approached his subjects with respect and aimed for authenticity within the context of his time, modern perspectives may critique certain portrayals as potentially romanticized or viewed through an outsider's lens. It's important to acknowledge the historical context in which he worked while remaining sensitive to contemporary discussions about cultural representation. His work remains valuable as a historical record, but like all depictions of cultural subjects, invites ongoing interpretation.

His legacy also includes his family. His son, Charles Berninghaus, followed in his father's footsteps, becoming a respected painter of Southwestern scenes, continuing the family's artistic connection to Taos.

Legacy: Chronicler of the Southwest

Oscar E. Berninghaus left an indelible mark on American art. His most significant legacy lies in his contribution to the formation and success of the Taos Society of Artists, a group that played a crucial role in bringing the art of the American Southwest to national prominence and defining a key chapter in American regionalism.

His paintings themselves constitute a vital record of northern New Mexico during a period of significant cultural transition. He captured the landscapes, the people, and the unique quality of light with a sensitivity and skill that continues to resonate. His work is characterized by its strong composition, harmonious color, and authentic depiction of his chosen subjects, particularly the Pueblo Indians of Taos.

Today, Berninghaus's paintings are highly sought after by collectors and are held in the permanent collections of major American museums, including the Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, the Stark Museum of Art in Orange, Texas, the Autry Museum of the American West in Los Angeles, the Denver Art Museum, the New Mexico Museum of Art, and the Saint Louis Art Museum, among others. His work is considered essential to understanding the development of Western American art.

He is remembered not just as a skilled painter but as a dedicated chronicler of a specific time and place, whose vision helped shape America's perception of its own Southwestern heritage. His commitment to Taos, both as a subject and as a community, ensured his place as one of its most defining artists.

Conclusion

From his early days in the printing houses of St. Louis to his final years as a revered elder of the Taos art colony, Oscar E. Berninghaus dedicated his life to art. His transformative encounter with New Mexico in 1899 set the course for a career devoted to capturing the unique beauty and cultural richness of the American Southwest. As a founding member of the Taos Society of Artists, he was instrumental in establishing Taos as a major center for American art. His paintings, characterized by their impressionistic handling of light and color, strong composition, and empathetic portrayal of Native American life and the Southwestern landscape, stand as an enduring testament to his talent and his deep connection to the region. Oscar E. Berninghaus remains a significant figure, whose work offers a valuable window into the art and history of the American West.