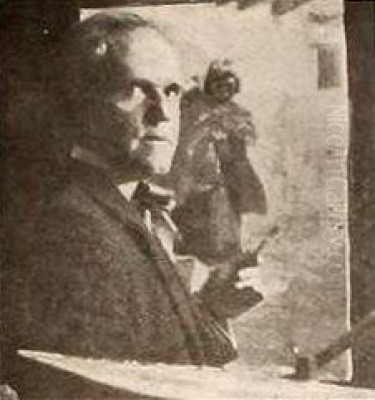

Gerald Cassidy stands as a significant, if sometimes underappreciated, figure in the canon of American Western art. Active during a transformative period in the early twentieth century, he dedicated his artistic endeavors to capturing the unique landscapes, indigenous cultures, and burgeoning art scene of New Mexico. His journey from a promising commercial artist in the East to a foundational member of the Santa Fe art colony is a compelling narrative of adaptation, passion, and an enduring connection to the spirit of the Southwest. Though his life was tragically cut short, Cassidy left behind a body of work that continues to resonate with its honesty, vibrant palette, and deep empathy for his subjects.

Early Life and Artistic Awakenings

Born Ira Dymond Gerald Cassidy in Covington, Kentucky, on November 10, 1879 (though some sources cite 1869, 1879 is more widely accepted and aligns with his career milestones), he spent his formative years in Cincinnati, Ohio. This bustling city, a significant cultural and artistic hub in the Midwest, provided the young Cassidy with his initial exposure to the world of art. He received his foundational training at the Mechanics Institute in Cincinnati, a respected institution known for its practical approach to arts education.

During his time at the Mechanics Institute, Cassidy had the invaluable opportunity to study under Frank Duveneck. Duveneck, a highly influential American figure painter and etcher, had returned to Cincinnati after years in Munich and Italy, bringing with him the vigorous brushwork and darker palettes characteristic of the Munich School. Duveneck's tutelage undoubtedly instilled in Cassidy a strong technical grounding and an appreciation for expressive realism, elements that would later manifest in his Southwestern works, albeit transformed by the brilliant light of New Mexico.

Seeking to further hone his skills and immerse himself in a more dynamic artistic environment, Cassidy, like many aspiring artists of his generation, made his way to New York City. There, he enrolled at the prestigious Art Students League, a crucible for American modernism and a place where traditional academic training coexisted with newer, more progressive ideas. The League exposed him to a diverse range of artistic philosophies and techniques, further broadening his artistic horizons. His talent was evident early on; by the remarkably young age of twenty, Cassidy had secured the position of art director for a prominent lithography company in New York, a testament to his skill and ambition in the competitive world of commercial art.

A Fateful Turn: Health and the Allure of the Southwest

Cassidy's burgeoning career in New York, however, took an abrupt and life-altering turn. Around 1899 or 1900, he was diagnosed with a severe case of pneumonia, which rapidly developed into tuberculosis. In an era before effective antibiotic treatments, such a diagnosis was often a death sentence. His physicians offered a grim prognosis, giving him perhaps only six months to live. The recommended course of action was a move to a drier climate, a common prescription for "lungers," as tuberculosis patients were then known.

This medical advice led Cassidy to a sanatorium in Albuquerque, New Mexico. While the move was born of dire necessity, it proved to be the most pivotal event in his artistic life. The stark, luminous beauty of the New Mexican landscape, the vibrant cultures of the Pueblo and Navajo peoples, and the unique quality of the high desert light made an indelible impression on him. What began as a fight for survival transformed into a profound artistic awakening. The Southwest, with its ancient traditions and dramatic scenery, offered a wealth of subject matter far removed from the urban landscapes and commercial demands of New York.

During his convalescence, Cassidy began to sketch and paint the people and places around him. He was captivated by the dignity and resilience of the Native American communities, their intricate crafts, and their deep connection to the land. This period marked the true beginning of his lifelong artistic engagement with the Southwest, a theme that would dominate his oeuvre and define his legacy.

Denver and a Developing Vision

After a period of recovery in Albuquerque, where the arid climate indeed proved beneficial to his health, Cassidy relocated to Denver, Colorado. In Denver, he re-engaged with commercial art, working as an illustrator and lithographer. His experiences in New Mexico, however, had irrevocably shaped his artistic interests. He increasingly focused his commercial work on Southwestern themes, particularly depictions of the Navajo people.

His illustrations and prints from this period began to gain recognition, showcasing his evolving ability to capture the character of his subjects and the atmosphere of the region. He produced posters and other materials that often featured Native American figures, rendered with a sensitivity that distinguished his work. This Denver interlude allowed him to refine his skills in depicting these new subjects while still earning a living, bridging the gap between his commercial obligations and his burgeoning passion for easel painting focused on the Southwest. It was also during this period that he began to shed some of the more decorative, Art Nouveau-influenced stylistic tendencies of his earlier New York work, moving towards a more direct and realistic portrayal.

Santa Fe: The Heart of His Art

In 1912, Gerald Cassidy, along with his wife, the writer and journalist Ina Sizer Davis (whom he married that same year), made the definitive move to Santa Fe, New Mexico. This decision placed them at the vanguard of what would become one of America's most important regional art centers. Santa Fe, with its unique tri-cultural heritage (Native American, Hispanic, and Anglo), its stunning natural setting, and its distinctive adobe architecture, was beginning to attract artists and writers seeking an alternative to the established art centers of the East Coast and Europe.

Cassidy was among the very first professional artists to establish permanent residence in Santa Fe, predating the formal organization of groups like Los Cinco Pintores by several years. He and Ina quickly became integral figures in the town's burgeoning cultural life. Their home, located on Canyon Road (a street that would later become synonymous with art galleries), became a welcoming hub for visiting artists, writers, and intellectuals.

He was a founding member of the Santa Fe Artists, a loose collective that, along with the Taos Society of Artists (founded by figures like Bert Geer Phillips, Ernest L. Blumenschein, Joseph Henry Sharp, E. Irving Couse, Oscar E. Berninghaus, and W. Herbert Dunton), played a crucial role in establishing the Southwest as a vital region for American art. Other artists who were part of the early Santa Fe scene or who would soon contribute to its vibrancy included Carlos Vierra, known for his architectural paintings and advocacy for Pueblo-Spanish architectural styles; Sheldon Parsons, the first director of the Museum of New Mexico's art gallery; and William Penhallow Henderson, an artist versatile in painting, architecture, and furniture design. Later, artists like Gustave Baumann, with his exquisite woodblock prints, and John Sloan, a leading figure of the Ashcan School who became a regular summer visitor and influential presence, would further enrich the artistic milieu.

Artistic Style and Thematic Focus

Gerald Cassidy's artistic style underwent a noticeable evolution throughout his career. His early commercial work in New York bore traces of the prevailing Art Deco and Art Nouveau aesthetics, characterized by decorative lines and stylized forms. However, his immersion in the Southwest prompted a shift towards a more realistic and expressive approach.

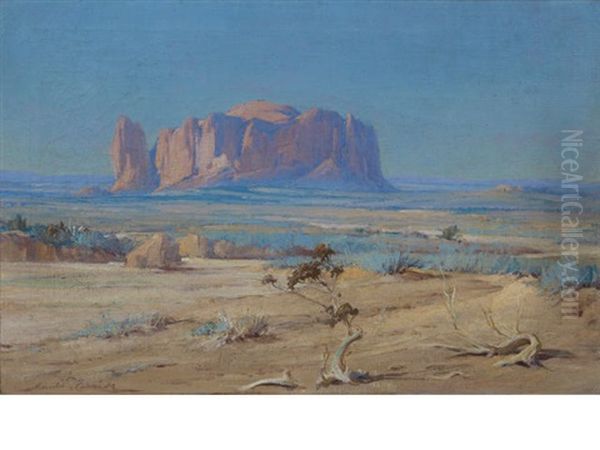

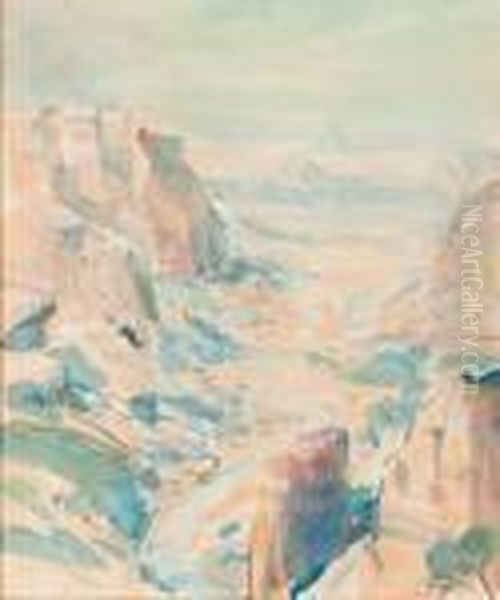

The brilliant, clear light of New Mexico became a central element in his paintings. He developed a palette that, while rich and vibrant, accurately captured the sun-drenched earth tones, the intense blues of the sky, and the subtle variations of color in the desert landscape. His brushwork became more fluid and confident, effectively conveying texture and form.

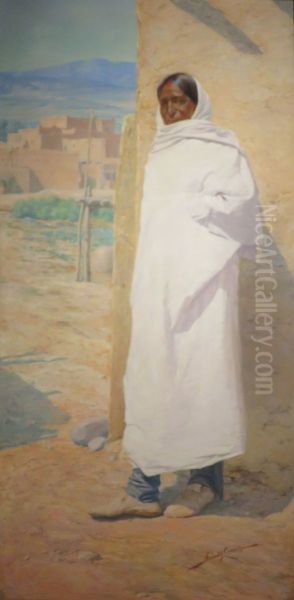

Cassidy's primary thematic focus was the people and landscapes of the American Southwest. He painted numerous portraits of Native Americans, particularly from the Pueblo and Navajo communities. These were not romanticized or stereotypical depictions but rather sensitive portrayals that sought to capture the individuality, dignity, and cultural identity of his subjects. He often depicted them engaged in daily activities, ceremonies, or simply in quiet contemplation, set against the backdrop of their ancestral lands. Works like "Cui Bono?" (a striking portrait of a Pueblo man) exemplify this empathetic approach.

His landscapes were equally compelling, showcasing the vastness and unique geological formations of the region. He painted the mesas, canyons, and adobe structures with a keen eye for atmospheric effects and the interplay of light and shadow. He was also adept at mural painting, a medium that allowed him to explore historical and cultural narratives on a larger scale.

Notable Works, Murals, and Achievements

Gerald Cassidy's talent garnered significant recognition during his lifetime. One of his most prestigious accolades was the gold medal awarded at the 1915 Panama-California International Exposition in San Diego. This event was a major showcase for American art, and winning a gold medal there significantly raised Cassidy's profile. The award-winning works often depicted scenes of Pueblo life, demonstrating his mastery in this area.

Cassidy was also a prolific muralist. He was commissioned to create murals for various public and commercial buildings. Among his most important mural projects were those for the U.S. Post Office and Federal Building in Santa Fe. One significant mural, depicting the life of the Pueblo Indians, was commissioned by Edgar Lee Hewett, the influential archaeologist and director of the Museum of New Mexico. Hewett played a crucial role in promoting Southwestern culture and art, and his patronage was vital for many artists in the region, including Cassidy. This particular mural was later purchased by Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes and donated to the National Archives.

He also created a series of four murals for the Lensic Theatre (originally the Santa Fe Plaza Theatre), depicting historical scenes, including the first encounters between Spanish explorers and Native Americans. These large-scale works allowed him to explore grand historical themes and contribute to the visual identity of Santa Fe's public spaces.

Beyond paintings and murals, Cassidy's art reached a wide audience through other mediums. He designed stamps and created numerous illustrations for postcards and posters, often featuring Navajo and other Native American subjects. These commercially reproduced images helped to popularize Southwestern art and culture across the nation and even internationally. His work was reportedly selected by none other than Pablo Picasso for an exhibition at the Luxembourg Palace in Paris, indicating a degree of European recognition for his distinctive American vision. Two large oil paintings were also completed for the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway, a major patron of Southwestern art, and for the French government.

Influences and Contemporaries: A Rich Artistic Milieu

Cassidy's artistic development was shaped by a confluence of influences and interactions with his contemporaries. His early training under Frank Duveneck provided a solid academic foundation. The environment of the Art Students League in New York, with teachers like Robert Henri (though it's unclear if Cassidy studied directly with him, Henri's influence on American realism and encouraging artists to depict American life was pervasive), would have exposed him to diverse artistic currents. Artists like George Bellows and Edward Hopper were also associated with the League around this period, highlighting the vibrant atmosphere of artistic exploration.

In the Southwest, the Taos Society of Artists, though geographically distinct from Santa Fe, created a powerful precedent for artists focusing on Native American themes and Southwestern landscapes. Figures like Ernest L. Blumenschein, Bert Geer Phillips, and Joseph Henry Sharp were pioneers in this regard, and their success helped to validate the Southwest as a serious subject for American art. Cassidy shared their commitment to depicting the region with authenticity and respect.

Within Santa Fe itself, Cassidy was part of a close-knit community. He collaborated and exchanged ideas with fellow artists like Carlos Vierra, who was instrumental in documenting and preserving the region's unique architecture. William Penhallow Henderson, another early Santa Fe resident, brought a sophisticated design sensibility that complemented the more painterly approaches of others. The arrival of artists like Gustave Baumann, known for his meticulous color woodcuts, and Randall Davey, with his vibrant paintings, further enriched the artistic dialogue in Santa Fe. Fremont Ellis, Willard Nash, and Will Shuster, who would later form part of Los Cinco Pintores, represented a younger generation pushing towards more modernist interpretations, but the groundwork laid by Cassidy and his early contemporaries was crucial for their development.

Edgar Lee Hewett, though not an artist, was a towering influence as a patron and cultural entrepreneur. His vision for the Museum of New Mexico and his commissioning of artists like Cassidy to document Pueblo life provided crucial support and direction for the burgeoning art scene. Ina Sizer Cassidy, Gerald's wife, was also an important figure, a writer who chronicled the art and culture of the region, contributing to its national recognition.

The Santa Fe Art Colony and Cassidy's Enduring Role

Gerald Cassidy was more than just a resident artist in Santa Fe; he was a foundational pillar of its art colony. Arriving in 1912, he was one of the very first Anglo artists to make Santa Fe his permanent home and dedicate his career to interpreting its unique character. The establishment of an art colony in Santa Fe was a somewhat organic process, driven by the region's compelling subject matter, its "exotic" cultures (from an Eastern perspective), the quality of its light, and a lower cost of living compared to major urban centers.

Cassidy, along with his wife Ina, actively fostered this nascent community. Their home on Canyon Road served as an early gathering place, fostering a spirit of camaraderie and intellectual exchange among artists, writers, and other cultural figures. He participated in early exhibitions at the Museum of New Mexico, which opened its art galleries in 1917 and became the institutional heart of the Santa Fe art scene.

His commitment to depicting the local Native American cultures with respect and accuracy set a high standard. While some artists of the era were criticized for romanticizing or exoticizing their subjects, Cassidy's work generally aimed for a more direct and empathetic portrayal. He understood the importance of preserving a visual record of cultures that were undergoing rapid change. His efforts, alongside those of Hewett and other artists, contributed to a growing national appreciation for Native American art and culture, moving beyond purely anthropological interest to aesthetic admiration.

The Santa Fe art colony, like its counterpart in Taos, played a significant role in shaping the narrative of American art in the early 20th century. It offered an alternative to European modernism and East Coast academicism, focusing instead on distinctly American subjects and regional identities. Cassidy's pioneering presence and his consistent artistic output were instrumental in establishing Santa Fe's reputation as a vital center for this new direction in American art.

Later Years and Tragic Demise

Throughout the 1920s and into the early 1930s, Gerald Cassidy continued to be a productive and respected artist. He undertook various commissions, including the aforementioned murals, and his easel paintings were sought after by collectors. He remained an active participant in the Santa Fe art community, witnessing its growth and diversification as more artists were drawn to the region.

His dedication to his craft, particularly to large-scale mural work, would, however, lead to his untimely death. In 1934, while working on a Public Works of Art Project commission to create murals for the dome of the Federal Building in Santa Fe, Cassidy was exposed to toxic materials. Specifically, he suffered from lead poisoning, likely from the paints he was using, and possibly exacerbated by carbon monoxide poisoning from a poorly ventilated gas heater used to keep the workspace warm during cold weather while he painted.

Despite medical efforts, his health deteriorated rapidly. Gerald Cassidy died on February 12, 1934, in Santa Fe, at the age of 54 (or 64, depending on the birth year used). His death was a significant loss to the American art world and particularly to the Santa Fe community, where he was a beloved and influential figure. The murals in the Federal Building remained unfinished, a poignant reminder of a career cut short.

Legacy and Historical Significance

Gerald Cassidy's legacy is multifaceted. He is remembered as a pioneer of the Santa Fe art colony, one of the first artists to recognize and articulate the unique artistic potential of New Mexico. His work provided an invaluable visual record of the Southwestern landscape and its Native American inhabitants during a period of significant cultural transition.

His paintings are prized for their technical skill, their vibrant yet sensitive use of color, and their empathetic portrayal of indigenous peoples. He successfully navigated the line between representational art and a more modern sensibility, creating works that were both accessible and artistically sophisticated. His influence can be seen in the subsequent generations of artists who were drawn to the Southwest, inspired by the path he helped to forge.

Museums across the United States, particularly those specializing in Western American art, hold his works in their collections, including the New Mexico Museum of Art in Santa Fe, the Stark Museum of Art in Orange, Texas, and the Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma. His home on Canyon Road, which he and Ina Sizer Cassidy built and expanded, stands as a historic landmark, a testament to their foundational role in Santa Fe's cultural history.

While perhaps not as widely known today as some of his Taos contemporaries or later Southwestern modernists, Gerald Cassidy's contribution is undeniable. He was an artist who found his true voice in the light and land of New Mexico, and in doing so, helped to define a significant chapter in American art history. His dedication to capturing the spirit of the Southwest ensures his enduring place as a key figure in the artistic heritage of the region.

A Luminous Vision Preserved

Gerald Cassidy's life and art offer a compelling window into the American Southwest at the dawn of the twentieth century. Driven by a profound connection to the region's landscape and its people, he translated his experiences into a body of work characterized by its vibrant color, sensitive portrayal, and enduring artistic merit. From his early training with masters like Frank Duveneck to his pivotal role in establishing the Santa Fe art colony alongside figures like Carlos Vierra and Sheldon Parsons, and his interactions with the broader artistic currents that included the Taos Society and visiting luminaries, Cassidy forged a unique artistic path. His award-winning paintings, significant murals, and widely circulated illustrations captured the essence of a changing West, leaving a rich legacy that continues to inform our understanding of this iconic American region. Though his career was tragically shortened, Gerald Cassidy's luminous vision of the Southwest remains a vital and cherished part of America's artistic tapestry.