Walter Ufer stands as a significant figure in the landscape of early 20th-century American art, particularly renowned for his vibrant and empathetic portrayals of Native American life in the Southwestern United States. A key member of the Taos Society of Artists, Ufer's work is characterized by its brilliant light, strong compositions, and a profound engagement with the social and cultural realities of his subjects. His journey from a German immigrant family in Kentucky to the sun-drenched mesas of New Mexico is a compelling story of artistic development and personal conviction.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Walter Ufer was born on July 22, 1876, in Louisville, Kentucky, to German immigrant parents. His father, a master gunsmith, instilled in him a sense of precision and craftsmanship, qualities that would later manifest in his meticulous approach to painting. The Ufer family's German heritage and connections likely played a role in young Walter's early exposure to European artistic traditions, even from afar. Louisville, a bustling river city, provided a diverse environment, but Ufer's artistic inclinations soon sought broader horizons.

His formal artistic training began not in the established art centers of the American East Coast, but in Europe. Recognizing his talent, his family supported his decision to travel to Germany. He initially apprenticed as a lithographer and typesetter in Hamburg, gaining practical skills in graphic arts. This early training in printmaking techniques may have influenced his later strong sense of design and composition in his paintings. However, his ambition lay in the realm of fine art, leading him to pursue more formal academic instruction.

European Sojourn and Academic Foundations

Ufer's pursuit of artistic excellence led him to Dresden, where he enrolled in the prestigious Royal Academy of Fine Arts. Here, he immersed himself in the rigorous academic training of the time, which emphasized drawing from life, anatomical studies, and the mastery of classical techniques. The European art scene at the turn of the century was a dynamic mix of established academicism and emerging modernist movements. While Ufer absorbed the discipline of the academy, he was also exposed to the currents of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism that were revolutionizing European art, with artists like Claude Monet and Paul Cézanne leading the charge.

After his studies in Dresden, Ufer spent time in other European art centers, including Munich, which was a particularly vibrant hub for artists. He studied under notable German painters such as Otto Strützel, Walther Firle, and Carl von Marr. These instructors, while rooted in academic traditions, were also part of a generation grappling with new ways of seeing and representing the world. This period was crucial for Ufer, allowing him to hone his technical skills while broadening his artistic perspectives. He absorbed the European emphasis on plein air painting and the expressive use of color, elements that would become hallmarks of his later work.

Upon returning to the United States, Ufer initially settled in Chicago. He found work as a commercial artist and illustrator, a common path for many artists of the era to support themselves. He also taught art, sharing his European-acquired knowledge with students. Chicago, at this time, was a burgeoning city with a growing arts scene, influenced by figures like Robert Henri and the Ashcan School, who advocated for depicting contemporary American life with unvarnished realism. While Ufer engaged with the commercial art world, his desire to create more personal and significant work remained strong. This ambition led him back to Munich in 1911 for further study, seeking to deepen his artistic voice before embarking on the most defining chapter of his career.

The Call of Taos: A New Artistic Frontier

The pivotal moment in Walter Ufer's artistic journey came in 1914. Through the patronage of Carter Harrison Jr., the former mayor of Chicago and an avid art collector, Ufer was sponsored to travel to Taos, New Mexico. Harrison, like many art patrons of the time, was intrigued by the American West and its indigenous cultures, seeing it as a uniquely American subject matter. For Ufer, this journey was transformative. The stark beauty of the New Mexico landscape, the intense clarity of the light, and the rich cultural heritage of the Pueblo people captivated him immediately.

Taos, a small, ancient settlement nestled in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, was already beginning to attract artists drawn to its unique atmosphere. The high desert environment, with its dramatic skies and earth-toned adobes, offered a visual palette unlike anything Ufer had experienced in Europe or the American Midwest. More importantly, the presence of the Taos Pueblo, one of the oldest continuously inhabited communities in North America, provided a profound human subject. Ufer found in the Pueblo people a dignity, resilience, and deep connection to their land that resonated with his artistic and personal sensibilities. He decided to make Taos his permanent home, a decision that would shape the rest of his artistic career.

Founding and Flourishing with the Taos Society of Artists

Soon after his arrival, Ufer became deeply involved with the artistic community that was coalescing in Taos. In 1915, the Taos Society of Artists (TSA) was formally established by a group of six painters: Bert Geer Phillips, Ernest L. Blumenschein, Joseph Henry Sharp, Oscar E. Berninghaus, E. Irving Couse, and W. Herbert "Buck" Dunton. Their mission was to promote the art of Taos and the Southwest, sending traveling exhibitions of their work to major cities across the United States. Walter Ufer officially joined the Society in 1917, becoming one of its most dynamic and influential members.

The TSA artists, often referred to as the "Taos Ten" after later members like Victor Higgins, E. Martin Hennings, and Kenneth Adams joined, shared a common fascination with the region's landscape and its native inhabitants. However, each artist brought a unique style and perspective. Ufer, with his European training and modernist leanings, contributed a distinctive voice. He was known for his strong compositions, vibrant color palette, and a more direct, less romanticized portrayal of his subjects compared to some of his peers. He collaborated closely with other members, sharing ideas and participating in the Society's collective efforts to gain national recognition for Southwestern art. The TSA played a crucial role in popularizing images of the American West and its indigenous peoples, shaping the nation's perception of this unique region.

Ufer's Distinctive Artistic Vision: Style and Subject Matter

Walter Ufer's artistic style was a synthesis of his European academic training and his embrace of modern color theories and Impressionistic techniques. He was particularly noted for his use of a high-key palette, employing bright, often unmodulated colors to capture the intense sunlight of New Mexico. His brushwork was vigorous and expressive, sometimes incorporating elements of Pointillism to create a sense of shimmering light and texture. Artists like Claude Monet, with his studies of light and atmosphere, and Paul Cézanne, with his emphasis on underlying structure and form, were clear influences, yet Ufer adapted these European sensibilities to the unique conditions of the American Southwest.

His primary subject matter was the Pueblo Indians of Taos and the surrounding areas. Unlike some of his contemporaries who tended to romanticize Native American life or focus solely on ceremonial aspects, Ufer often depicted his subjects in their everyday activities – working in the fields, resting in the shade, or engaged in quiet moments of contemplation. He sought to portray them with dignity and individuality, avoiding stereotypical representations. His figures are often monumental, imbued with a sense of strength and presence. The landscape itself was a crucial element in his compositions, not merely a backdrop but an active participant in the lives of the people he painted. The adobe structures, the vast skies, and the distinctive flora of the region are rendered with a keen eye for detail and a deep appreciation for their inherent beauty.

Ufer's approach was rooted in realism, but it was a realism infused with his personal response to the subject. He was less interested in ethnographic documentation than in capturing the human spirit and the interplay of light, color, and form. His compositions are often bold and dynamic, sometimes employing unusual perspectives or cropping to heighten the visual impact. He was a master of depicting the human figure in strong sunlight, skillfully rendering the effects of light and shadow on form and color.

Masterworks: Illuminating Native American Life

Several of Walter Ufer's paintings stand out as iconic representations of his artistic vision and his engagement with the Pueblo culture. The Solemn Pledge, Taos (c. 1916) is one such masterpiece. The painting depicts three generations of Taos Pueblo men, possibly engaged in a moment of cultural transmission or a significant discussion. The figures are rendered with a quiet monumentality, their expressions thoughtful and serious. Ufer's use of color is particularly striking, with the vibrant hues of their blankets and the sun-drenched adobe walls creating a powerful visual statement. The composition draws the viewer into the intimate scene, highlighting the importance of tradition and community.

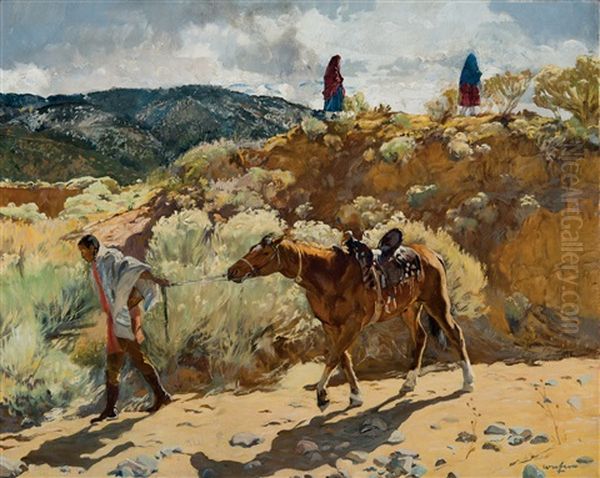

Another significant work, Trailing Homeward (c. 1924), showcases Ufer's ability to capture the atmosphere and light of the New Mexico landscape. The painting depicts figures on horseback moving through a luminous, sun-filled environment. The colors are brilliant, almost dazzling, conveying the heat and intensity of the desert sun. The brushwork is energetic, contributing to the sense of movement and the shimmering quality of the light. This work exemplifies Ufer's skill in integrating figures and landscape into a harmonious and evocative whole.

Other notable paintings include His Land, which portrays a solitary Native American figure surveying a vast expanse, suggesting a deep connection to and perhaps a concern for the ancestral territory. Hunger is a more somber work, hinting at the economic hardships faced by the Pueblo people. The Fiddler of Taos captures a moment of cultural expression, while works like Bob Abbott and His Assistant (also known as Jim and His Daughter) show Ufer's interest in portraying individuals with distinct personalities. In many of his works, Ufer included elements of modern life, such as automobiles or contemporary clothing, alongside traditional elements, reflecting the changing realities of Pueblo life in the early 20th century. This refusal to present a purely idealized or static image of Native American culture was a hallmark of his honesty as an observer.

A Voice for the Voiceless: Social Consciousness in Art

Beyond his aesthetic achievements, Walter Ufer was distinguished by his strong social conscience. He was an avowed socialist and a vocal advocate for the rights of Native Americans. He was deeply aware of the injustices and hardships faced by the Pueblo people, including issues of land rights, poverty, and the pressures of assimilation. This social awareness often found its way into his art, though usually subtly rather than overtly.

Ufer's paintings, while celebrating the beauty and dignity of Pueblo life, also sometimes hinted at the underlying struggles. He depicted his subjects not as exotic curiosities but as individuals with complex lives and emotions. His commitment to realism extended to acknowledging the contemporary realities of their existence, including their labor and their interactions with the encroaching modern world. He was known to have participated in protests and supported the efforts of the Pueblo people to protect their land and culture. This active engagement set him apart from many artists of his time who might have admired Native American culture from a distance but were less involved in their social and political concerns.

His empathy for the working class, likely stemming from his socialist beliefs, also informed his portrayal of labor. Whether depicting Pueblo Indians tending their fields or engaged in other forms of work, Ufer imbued these scenes with a sense of respect for the dignity of labor. His art, therefore, can be seen not only as a celebration of Southwestern culture but also as a quiet form of social commentary, reflecting his deep concern for human rights and social justice. This aspect of his work adds another layer of significance to his artistic legacy, positioning him as an artist who used his talents to engage with the pressing issues of his time.

Challenges and Complexities: The Man Behind the Canvas

Walter Ufer's life, like his art, was marked by complexities and challenges. He was known for his strong personality, sometimes described as irascible or difficult. His relationship with his patron, Carter Harrison Jr., while initially supportive, became strained over time. Despite Harrison's crucial role in enabling Ufer's move to Taos, Ufer reportedly harbored some resentment or dissatisfaction, a common enough occurrence in patron-artist relationships where expectations and personalities can clash.

A more significant personal struggle for Ufer was his battle with chronic alcoholism. This affliction undoubtedly took a toll on his health and may have impacted his productivity and personal relationships. The life of an artist, particularly in a relatively isolated community like Taos, could be demanding, and the pressures of maintaining a career and producing work could be immense. Alcoholism was, unfortunately, not uncommon among artists of that era, and Ufer's struggles were a source of concern for his friends and colleagues.

Despite these personal challenges, Ufer continued to produce a remarkable body of work. His dedication to his art remained unwavering, and he achieved considerable success and recognition during his lifetime. His complex personality and personal battles are part of his story, adding a human dimension to the image of the celebrated artist. These struggles perhaps even fueled some of the intensity and emotional depth found in his paintings, reflecting a man who experienced life's highs and lows with passion.

Recognition, Legacy, and Enduring Influence

Walter Ufer achieved significant recognition during his career. His work was exhibited widely, including at prestigious venues such as the Carnegie International in Pittsburgh, where he won awards, and the National Academy of Design in New York, which elected him as an Associate in 1920 and a full Academician in 1926. His paintings were acquired by major museums, including the Art Institute of Chicago, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, the New Mexico Museum of Art, the Denver Art Museum, and the Indianapolis Museum of Art, ensuring their accessibility to future generations.

His auction prices also reflected his standing in the art world. For instance, his painting Trailing Homewards fetched a remarkable $613,000 at a Scottsdale Art Auction, significantly exceeding its estimate and underscoring the continued market appreciation for his work. This commercial success, coupled with critical acclaim, solidified his reputation as one of the leading figures of the Taos art colony.

Ufer's legacy extends beyond his individual achievements. As a prominent member of the Taos Society of Artists, he contributed to a movement that brought a new vision of the American West to national and international audiences. The Society helped to establish Taos as a major art center and fostered a uniquely American school of painting. Ufer's influence can be seen in the work of later artists who were drawn to the Southwest, inspired by his bold use of color, his strong compositions, and his empathetic portrayal of Native American subjects. Artists like Georgia O'Keeffe, who also found inspiration in the New Mexico landscape, and later generations of Western artists, owe a debt to pioneers like Ufer who first captured its unique spirit.

Ufer in the Pantheon of Western American Art

Walter Ufer's place in the pantheon of Western American art is secure. He was more than just a painter of picturesque scenes; he was an artist who engaged deeply with his subjects, bringing a modernist sensibility to the depiction of a traditional culture. His work transcends mere regionalism, addressing universal themes of human dignity, cultural identity, and the relationship between people and their environment. He stands alongside other great interpreters of the West, such as Frederic Remington and Charles M. Russell, though his approach and style were distinctly different, focusing less on the action-packed narratives of the "Wild West" and more on the contemporary lives and inner worlds of the Pueblo people.

His commitment to portraying Native Americans with honesty and respect, coupled with his advocacy for their rights, adds a significant ethical dimension to his artistic contributions. In an era when Native American cultures were often misunderstood or romanticized, Ufer sought to present a more nuanced and authentic vision. His paintings serve as a valuable historical and cultural record, capturing a specific time and place with artistic brilliance and profound human insight. Walter Ufer passed away on August 2, 1936, but his vibrant canvases continue to speak to us, offering a luminous window onto the world he knew and cherished. His art remains a testament to the enduring power of the human spirit and the captivating beauty of the American Southwest.