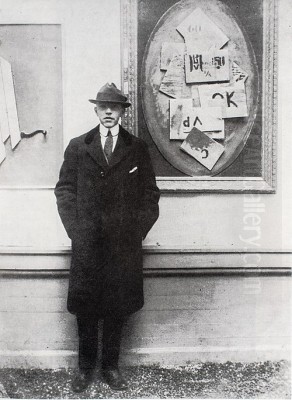

Vilhelm Lundstrøm (1893-1950) stands as a pivotal figure in the narrative of 20th-century Danish art. A painter celebrated primarily for his compelling still lifes and modernist sensibilities, Lundstrøm navigated the turbulent currents of European art, absorbing transformative ideas and forging a unique visual language that left an indelible mark on Scandinavian modernism. His career, spanning the dynamic first half of the century, witnessed a profound evolution in style, marked by rigorous formal exploration, a sophisticated understanding of color, and a commitment to the core tenets of modern art. He was not merely a participant but a key architect in shaping the direction of Danish painting during a period of significant aesthetic upheaval.

Lundstrøm's journey began in Copenhagen, born into a world on the cusp of radical change. While detailed accounts of his earliest training are less emphasized than his later achievements, it's clear he emerged within an artistic environment still grappling with the legacy of 19th-century realism and symbolism, represented by figures like Vilhelm Hammershøi, known for his quiet, evocative interiors, and the more flamboyant J.F. Willumsen. Lundstrøm, however, belonged to a generation eager to break from tradition and engage with the revolutionary artistic ideas emanating primarily from Paris. His formative years coincided with the rise of Fauvism, Expressionism, and, most crucially for his development, Cubism.

The Embrace of Cubism and Early Experiments

The early decades of the 20th century saw Paris as the undisputed center of the avant-garde. Like many aspiring artists across Europe, Lundstrøm looked towards France for inspiration. He became deeply influenced by the groundbreaking work of Cubist pioneers, particularly Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. Their deconstruction of form, representation of objects from multiple viewpoints simultaneously, and emphasis on geometric structure resonated profoundly with Lundstrøm's own burgeoning interest in formal analysis. He was also undoubtedly aware of the contributions of Paul Cézanne, whose late work is often seen as a crucial precursor to Cubism, emphasizing the underlying geometry of nature and building form through color planes.

Lundstrøm was among the first Danish artists to actively engage with and assimilate Cubist principles into his own work. This wasn't merely imitation; it was a process of translation and adaptation. He began experimenting with fragmented forms and flattened perspectives, applying these concepts predominantly to the genre that would become central to his oeuvre: the still life. His early Cubist-inspired works often featured everyday objects – jugs, bowls, fruit – reduced to their essential geometric components.

A particularly bold step was his introduction of Cubist collage techniques into the Danish art scene around 1917. Collage, as practiced by Picasso and Braque, involved incorporating materials like newspaper, wallpaper, or wood grain paper directly onto the canvas, challenging traditional notions of representation and the sanctity of the painted surface. Lundstrøm's adoption of this technique, creating what were sometimes referred to as "packing case pictures" due to their raw, assembled quality, marked a radical departure from established Danish artistic conventions. These works emphasized texture, the interplay of different materials, and a highly abstract, constructed reality.

Controversy and the "Dysmorphism" Debate

Lundstrøm's early embrace of Modernism, particularly his Cubist collages, was not met with universal acclaim in Denmark. In 1918, when he first exhibited these challenging works, they ignited a significant controversy. The radical departure from naturalistic representation was shocking to many conservative viewers and critics. The reaction was so intense that it led to what became known as the "dysmorphism debate."

This debate reached a peculiar climax when a biology professor publicly diagnosed Lundstrøm as mentally ill based on his art, suggesting his distorted forms were symptoms of a disturbed mind. Furthermore, a prominent physician, Dr. Carl J. Salomonsen, went so far as to pathologize modern art itself, viewing it as a form of contagious mental disease threatening cultural health. This incident highlights the profound cultural clash occurring at the time between traditional values and the burgeoning avant-garde movements sweeping across Europe. Lundstrøm found himself at the epicenter of this conflict in Denmark, his work becoming a lightning rod for anxieties about modernity and artistic experimentation.

Despite the controversy, or perhaps partly fueled by it, Lundstrøm continued his explorations. The resistance he encountered underscored the revolutionary nature of his work and solidified his position as a leading figure among Denmark's progressive artists. He was challenging the very definition of art and perception, forcing his audience to confront new ways of seeing the world.

Travels, Influences, and the "Carnival Images"

Like many artists of his generation, travel played a crucial role in Lundstrøm's development. A significant journey occurred in 1922 when he traveled to the South of France, staying in Bormes-les-Mimosas, a picturesque town near the Mediterranean coast. This region had long attracted artists with its vibrant light and landscape, famously drawing Post-Impressionists and Fauves. For Lundstrøm, this trip provided a specific, potent source of inspiration.

During his stay, he witnessed a local carnival, a spectacle of masks, costumes, and exuberant movement. This experience directly inspired a series of paintings known as the "Carnival Images." These works marked a departure from the stricter, more analytical geometry of his earlier Cubist phase, embracing instead a greater sense of dynamism and color. While still rooted in modernist principles, they captured the energy and visual richness of the folk festival, translating the fleeting moments of the parade into compositions alive with rhythm and pattern. This period demonstrates Lundstrøm's ability to absorb direct visual experiences and translate them through his evolving modernist lens.

His time in France also deepened his connection to French art. Beyond the initial Cubist influence, he continued to engage with the work of French masters. The structural solidity of Cézanne remained a touchstone, while the decorative aspects and color explorations of artists like Henri Matisse, a key figure in Fauvism, may also have informed his developing palette and compositional strategies, particularly as he moved towards greater simplification and color harmony.

Formation of "De Fire" (The Four)

Collaboration and artistic exchange were vital components of the modernist movement. Lundstrøm was a key participant in the formation of the influential Danish artist group known as "De Fire" (The Four). This collective, founded in the early 1920s, brought together Lundstrøm with fellow painters Karl Larsen, Svend Johansen, and the multi-talented artist Axel Salto, who was also renowned for his ceramics.

The group was particularly active during periods spent working together in the South of France. This shared experience fostered a close artistic dialogue and mutual influence among the members. They likely discussed theoretical ideas, critiqued each other's work, and experimented with shared themes or stylistic approaches. While each artist maintained his individual identity, their association provided a supportive environment for pushing the boundaries of Danish art. The collective exhibitions of "De Fire" were significant events, showcasing a unified front of modernist exploration to the Danish public.

The formation of groups like "De Fire" was characteristic of the era, mirroring similar associations in Paris and other European centers. These groups provided solidarity, platforms for exhibition, and intellectual stimulus, helping to consolidate and promote new artistic directions against often resistant established institutions. Lundstrøm's involvement underscores his role not just as an individual innovator but also as a catalyst within a community of like-minded artists seeking to redefine Danish painting.

Developing a Signature Style: Purism and the Still Life

Following his initial Cubist experiments and the dynamism of the "Carnival Images," Lundstrøm's style underwent a further refinement during the 1920s and 1930s. He moved towards a form of simplified, monumental modernism that showed affinities with Purism, an aesthetic movement championed in France by Amédée Ozenfant and the architect-painter Le Corbusier. Purism sought clarity, order, and objectivity, reacting against what its proponents saw as the decorative excesses of later Cubism. They favored clean lines, precise forms, and harmonious compositions based on everyday objects.

This Purist sensibility resonated strongly with Lundstrøm's evolving aesthetic. His paintings, particularly his still lifes, became increasingly characterized by their clarity, formal rigor, and serene balance. He pared down objects to their essential shapes – jugs, pitchers, bowls, fruit – arranging them in carefully constructed compositions. The palette often became more restrained, focusing on subtle harmonies and the interplay of light and shadow to define form, rather than fragmented planes. Works like Still Life with Orange, Books and Boxes exemplify this phase, showcasing a masterful control over composition and a quiet monumentality.

His dedication to the still life genre became a defining feature of his career. Lundstrøm returned to it again and again, exploring its formal possibilities with unwavering focus. Unlike traditional still lifes laden with symbolic meaning, Lundstrøm's arrangements were primarily investigations of form, color, and spatial relationships. He treated the objects almost as abstract elements, creating compositions that were self-contained and aesthetically pure. His 1931 Still Life, now housed in a Copenhagen museum, is a prime example of this mature style – balanced, harmonious, and imbued with a sense of timeless order.

The Human Form: Nudes and Idealization

While best known for his still lifes, Lundstrøm also engaged with the human figure, particularly the female nude. His approach to the nude, like his still lifes, was primarily formal. He treated the body as a structure of volumes and lines, exploring its contours and masses within the pictorial space. His nudes, often titled simply Nøgenhed (Nudity), avoid overt sensuality or psychological depth, focusing instead on the aesthetic qualities of the form itself. They possess a sculptural quality, rendered with the same clarity and simplification seen in his object studies.

An interesting work from this period is Idyle (1923). This painting, described as having a Dionysian character, suggests an engagement with classical themes but interpreted through a modern lens. It reportedly references French Romanticism while simultaneously showcasing his early Cubist-influenced style, perhaps indicating a moment of synthesis between historical inspiration and avant-garde techniques. The idealized figures and dynamic composition hinted at in descriptions suggest a departure from the static arrangements of his still lifes, exploring rhythm and movement within a figurative context.

His treatment of the nude can be seen in the context of other modernists who revisited this traditional genre, such as Picasso's monumental figures or Matisse's odalisques. Lundstrøm's nudes, however, maintain a distinct character – cool, objective, and integrated into his overall aesthetic of formal purity and balanced composition. They stand as further evidence of his consistent application of modernist principles across different subject matter.

The "Curling Style" and Stylistic Evolution

Lundstrøm's artistic journey was not linear. Alongside the development of his Purist-inflected style, sources mention a distinct phase referred to as the "curling style" (sometimes translated from Danish). This suggests a period where his characteristic clean lines and geometric rigor may have softened, incorporating more rounded, curvilinear forms. This "curling style" might be associated with works like Frokost i grønne (Lunch in Green), which is noted as being influenced by Cézanne and perhaps even Hergé (the creator of Tintin, known for his clear line style, though this connection might be more about visual affinity than direct influence).

This phase indicates Lundstrøm's willingness to continue experimenting and evolving throughout his career. The potential influence of Cézanne is logical, given the French master's importance for virtually all modernist painters in their exploration of structure and form. The reference to curves suggests a possible exploration of more organic shapes or a different approach to rendering volume, perhaps moving away slightly from the strict planarity of some of his more rigidly geometric works.

This stylistic flexibility demonstrates that Lundstrøm was not dogmatically attached to a single formula. While his core concerns remained focused on form, color, and composition, he allowed his visual language to adapt and change, absorbing new influences and exploring different expressive possibilities within the broader framework of modernism. His oeuvre, therefore, presents a rich tapestry of related but distinct stylistic investigations.

A Master of Composition and Color

Underlying all of Lundstrøm's stylistic phases was a fundamental mastery of composition and color. His works are consistently characterized by a strong sense of structure. He possessed an innate ability to arrange elements within the picture plane to achieve balance, harmony, and visual interest. Whether dealing with the complex arrangements of his early Cubist works or the simplified compositions of his mature still lifes, there is always a sense of deliberate and thoughtful organization.

His use of color was equally sophisticated. While sometimes employing vibrant hues, particularly in works like the "Carnival Images," he often favored restrained palettes. He understood the power of subtle color relationships and tonal variations to define form and create mood. His mature still lifes frequently feature harmonious combinations of blues, grays, ochres, and whites, applied in smooth, often unmodulated areas. This approach emphasizes the purity of the color and the clarity of the form, contributing to the serene, almost classical feel of these works.

Lundstrøm's technique involved clear, decisive lines and a focus on the essential shapes of objects. He often used light and shadow not just for naturalistic modeling, but as compositional elements in themselves, creating patterns and defining volumes in a way that reinforced the overall structure of the painting. The result is an art that feels objective and "unpolluted," as some descriptions note – free from excessive emotion or narrative, allowing the viewer to focus entirely on the formal qualities of the work. This dedication to the essential elements of painting aligns him with other modern masters like Giorgio Morandi, who similarly devoted his career to the meditative exploration of still life.

Educator and Mentor

Vilhelm Lundstrøm's contribution to Danish art extended beyond his own creative output. He held the prestigious position of Professor at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen. In this role, he was instrumental in shaping the development of subsequent generations of Danish artists. His teaching would have disseminated the principles of modernism that he himself had championed, providing students with a direct link to contemporary European art movements.

His presence at the Academy signified the institutional acceptance of modernism in Denmark, a significant shift from the controversies of his early career. As an educator, he likely emphasized the importance of formal rigor, compositional understanding, and color theory – the very principles that underpinned his own work. He joined other influential Danish modernists who were active as teachers or leading figures, such as Edvard Weie, Harald Giersing, and Olaf Rude, collectively helping to establish modern art as the dominant force in the Danish art scene by the mid-20th century.

His influence as a teacher ensured that his artistic ideas and methods would continue to resonate long after his death. He helped to train artists who would carry forward the legacy of Danish modernism, adapting and transforming it according to their own visions. This pedagogical role solidifies Lundstrøm's status not just as a painter, but as a foundational figure in the institutional and educational landscape of modern Danish art.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Wider Connections

From the 1920s onwards, Vilhelm Lundstrøm achieved significant recognition both within Denmark and internationally. His work became a regular feature in major Danish exhibitions, including those held at the prestigious Charlottenborg exhibition hall in Copenhagen. A centenary exhibition, "Vilhelm Lundstrøm 100 years," held after his lifetime, attests to his enduring importance. His paintings were also shown at important regional museums like the Fyens Kunstmuseum and the Randers Museum of Art.

His reputation extended beyond Scandinavia, with his work appearing in European exhibitions and galleries. Major museums acquired his paintings, including the renowned Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, located north of Copenhagen, which holds a significant collection of international modern art. This level of recognition confirmed his status as one of Denmark's leading modern artists, comparable in stature within the Danish context to internationally recognized modernists from other countries.

Beyond the art world, Lundstrøm also engaged in broader cultural activities. His collaboration with the Swedish classical archaeologist and cultural historian Axel Boethius on projects related to Swedish cultural history indicates intellectual curiosity beyond painting. Furthermore, his involvement in founding the Swedish-Italian Association demonstrates an interest in fostering international cultural exchange, reflecting the cosmopolitan outlook shared by many modern artists and intellectuals of the period.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Vilhelm Lundstrøm passed away in 1950, leaving behind a rich and complex body of work and a significant legacy. His primary contribution was his role as a conduit and interpreter of European modernism, particularly Cubism and Purism, for a Danish audience. He successfully translated these international styles into a distinctly Scandinavian idiom, characterized by clarity, formal strength, and often a cool, reserved palette.

His unwavering focus on the still life genre resulted in a profound and sustained exploration of form, color, and composition, making him one of the 20th century's notable masters of the genre. His work continues to be admired for its balance, technical refinement, and timeless quality. The controversies of his early career now serve as historical markers of the battles fought by the avant-garde to gain acceptance.

Lundstrøm's influence persists. Later artists have continued to draw inspiration from his work. For example, the contemporary ceramicist Nicholas Woodall has acknowledged the influence of Lundstrøm's still life paintings on his own explorations of form and arrangement. This demonstrates the lasting relevance of Lundstrøm's formal investigations across different mediums and generations.

In the grand narrative of modern art, Vilhelm Lundstrøm holds a secure place as a key figure in Danish Modernism. He navigated the complex artistic landscape of the early 20th century with intelligence and integrity, creating a body of work that is both historically significant and aesthetically compelling. His paintings remain a testament to the enduring power of formal exploration and the quiet beauty of ordered composition. He stands alongside other major Scandinavian modernists, contributing a unique voice to the broader conversation of 20th-century European art.