William Bell Scott (1811-1890) stands as a fascinating, if sometimes controversial, figure in the landscape of nineteenth-century British art and literature. A Scottish painter, etcher, poet, and educator, Scott navigated the complex currents of Victorian culture, leaving behind a diverse body of work that reflects the era's artistic ferment, industrial transformations, and intellectual debates. His life and career were intertwined with some of the most prominent artistic personalities of his time, most notably the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, and his contributions, though occasionally overshadowed, offer a rich insight into the period's aesthetic and social concerns.

Early Life and Artistic Genesis

Born in Edinburgh on September 12, 1811, William Bell Scott was immersed in an artistic environment from his earliest years. His father, Robert Scott (1777–1841), was a respected engraver, and his elder brother, David Scott (1806–1849), would also achieve recognition as a historical painter of considerable power and imagination, known for works like Vasco da Gama Encountering the Spirit of the Cape. This familial background provided William with a foundational training in the visual arts. He assisted his father in his engraving workshop, acquiring technical skills that would later inform his own printmaking.

Scott's intellectual and creative inclinations were not confined to the visual arts. He began writing poetry at a young age, publishing verses in Scottish magazines. His early artistic efforts were ambitious, and he sought recognition in London, the center of the British art world. In 1837, he sent his first oil painting, The Jester, to the Royal Academy. A significant early success came in 1844 when his painting, The Descent of Orpheus into Hades, received acclaim at the Royal Academy, marking his formal entry into the London art scene. This work, sometimes referred to by themes like "The Soul's Journey and Progress," demonstrated his interest in mythological and allegorical subjects, a common preoccupation among artists of the period.

His early artistic development was shaped by the prevailing academic traditions, but also by a burgeoning romantic sensibility. The influence of poets like William Blake and Percy Bysshe Shelley, whose works he would later edit, can be discerned in the imaginative and often philosophical underpinnings of his creative output, both visual and literary.

The Newcastle Years: Educator and Muralist

A pivotal moment in Scott's career arrived in 1843 when he was appointed Master of the Government School of Design in Newcastle upon Tyne. He would hold this position for two decades, until 1864, and his tenure proved to be highly influential, not only for the institution (which later became the Newcastle College of Art) but also for the artistic landscape of the North East of England. Scott was a dedicated and energetic educator, deeply involved in the organization of art teaching and examinations.

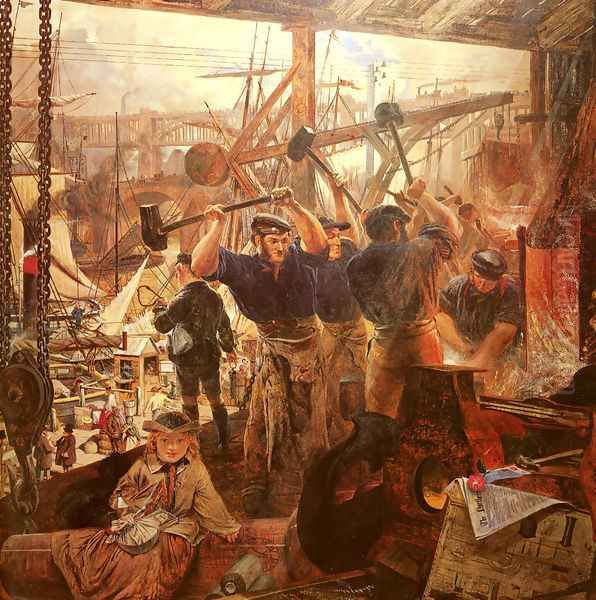

During his time in Newcastle, Scott championed the depiction of industrial subjects in art, a relatively novel concept at the time. The Industrial Revolution was transforming the British landscape and society, and Scott recognized the artistic potential in these new realities. This interest culminated in one of his most famous works, Iron and Coal (1855-1860), a painting that vividly captures the labor and machinery of Tyneside's burgeoning industries. This work is often cited as an important early example of industrial art, predating similar efforts by artists like Ford Madox Brown, whose own monumental painting Work (1852-1865) explored themes of contemporary labor.

Scott's most significant artistic undertaking during this period was the series of eight large historical murals for Wallington Hall in Northumberland, the seat of the Trevelyan family. Executed between 1856 and 1861, these murals depict scenes from Northumbrian history, from the Roman occupation to the local industrial age, including The Building of the Roman Wall, The Descent of the Danes, and Iron and Coal (a version of his easel painting theme). These works demonstrate Scott's commitment to historical narrative and his ability to work on a grand scale, contributing significantly to the Victorian revival of mural painting, a movement also championed by artists like William Dyce and Daniel Maclise. His students at Newcastle, such as Robert Jobling, Henry Hetherington Emmerson, and Ralph Hedley, benefited from his guidance and often reflected Pre-Raphaelite influences in their own work.

Association with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

William Bell Scott's connection with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB) is a defining aspect of his career and legacy. He formed a close and lasting friendship with Dante Gabriel Rossetti, one of the leading figures of the movement. Rossetti, along with William Holman Hunt and John Everett Millais, had founded the PRB in 1848, seeking to revitalize British art by rejecting the perceived artificiality of academic painting and embracing the directness and detailed naturalism of early Italian art.

Scott was not a founding member of the PRB, but he became a significant associate and supporter. His correspondence with Rossetti began around 1847, even before the formal establishment of the Brotherhood. Rossetti admired Scott's poetry, particularly the poem "Rosabell" (later published as Maryanne), and invited him to contribute to The Germ, the short-lived but influential journal of the PRB, which also featured contributions from Christina Rossetti, Thomas Woolner, and Coventry Patmore.

Scott's own artistic style shows the influence of Pre-Raphaelite principles, particularly in its attention to detail, symbolic content, and often literary or historical subject matter. Works like The Eve of the Deluge (1865) and Ailsa Craig (1860) exhibit a meticulous rendering of natural forms and a heightened emotional intensity characteristic of the movement. He shared their interest in medievalism, romance, and subjects drawn from literature, including the works of Keats and Tennyson, who were also favorites of Rossetti, Millais, and Arthur Hughes.

His relationship with the PRB extended beyond Rossetti. He maintained a long-standing connection with William Holman Hunt and was acquainted with other figures in their circle, including Ford Madox Brown, whose social realist tendencies resonated with Scott's own interest in contemporary life, and the younger generation of artists associated with the movement, such as Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris. Scott's engagement with the PRB was thus multifaceted, encompassing shared artistic ideals, personal friendships, and collaborative ventures.

Literary Endeavors: Poet and Critic

Parallel to his career as a painter and educator, William Bell Scott was a prolific writer. His poetic output was considerable, and he published several volumes of poetry throughout his life. His first collection, Hades; or, the Transit, and The Progress of Mind, appeared in 1838. This was followed by The Year of the World: A Philosophical Poem on "Redemption from the Fall" (1846), Poems by a Painter (1854), which included "Rosabell," and later collections such as A Poet's Harvest Home: Being One Hundred Short Poems (1882, enlarged 1893).

Scott's poetry often explored mystical, philosophical, and historical themes. He acknowledged the influence of William Blake and Percy Bysshe Shelley, and his verse is characterized by its imaginative scope and intellectual depth. His work was respected by his literary contemporaries, including Algernon Charles Swinburne, who became a close friend of both Scott and Rossetti.

Beyond his original poetry, Scott was an accomplished art critic and editor. He wrote extensively on art and artists, contributing articles to various periodicals. He also produced critical editions of the works of several major poets, including William Shakespeare, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, John Keats, and Percy Bysshe Shelley. These editions, often accompanied by biographical memoirs, showcased his scholarly abilities and his deep engagement with English literature. His Memoir of David Scott, R.S.A. (1850) provided valuable insights into his brother's life and art. Other prose works included Antiquarian Gleanings in the North of England (1851) and Half-Hour Lectures on the History and Practice of the Fine and Ornamental Arts (1861), the latter reflecting his educational concerns.

Personal Life, Penkill Castle, and Later Years

In his personal life, Scott formed a significant and enduring relationship with Alice Boyd, the sister of Spencer Boyd, then laird of Penkill Castle in Ayrshire, Scotland. Scott first visited Penkill in 1860, and it became a regular retreat and eventually his primary residence in his later years. Alice Boyd was herself an aspiring artist, and Scott encouraged her work. Their relationship, though complex (Scott was married to Letitia Margery Norquoy, though the marriage was reportedly not a happy one and they lived separately for many years), was a source of companionship and artistic inspiration for Scott.

At Penkill Castle, Scott undertook another significant decorative project, painting a series of murals on the staircase based on James I of Scotland's poem, The Kingis Quair. This project, executed in the late 1860s, further demonstrated his commitment to narrative art and his connection to Scottish history and literature. Penkill Castle became a gathering place for artists and writers in their circle, including Dante Gabriel Rossetti, who stayed there for extended periods, particularly during times of ill health, and Christina Rossetti.

Scott's later years were also marked by the compilation of his Autobiographical Notes, which were published posthumously in 1892, edited by W. Minto. These memoirs, while providing a wealth of information about his life and the Victorian art world, became a source of considerable controversy. His recollections and assessments of his contemporaries, particularly his portrayal of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, were criticized by some as being inaccurate, biased, and even malicious. This has somewhat complicated his posthumous reputation, leading to debates about his character and the reliability of his accounts. For instance, William Michael Rossetti, D.G.R.'s brother, took issue with many of Scott's assertions.

Artistic Style, Evolution, and Key Works

William Bell Scott's artistic style evolved throughout his long career, reflecting both his personal development and the changing artistic climate of the Victorian era. His early works, such as The Old English Ballad Singer (c. 1840s), show an inclination towards historical genre scenes, rendered with a competent, if somewhat conventional, technique.

The encounter with Pre-Raphaelitism marked a significant shift. While he never fully adopted the intense, jewel-like palette of early Millais or Hunt, his work gained in precision, detail, and symbolic depth. The Eve of the Deluge (1865), for example, depicts a scene of impending doom with a meticulous rendering of figures and landscape, imbued with a sense of psychological tension. His landscapes, such as Ailsa Craig (1860), often combine topographical accuracy with a romantic sensibility.

His most distinctive contribution, perhaps, lies in his historical and industrial subjects. The Wallington Hall murals are a major achievement in Victorian narrative painting, showcasing his ability to synthesize historical research with artistic imagination. Iron and Coal (both the Wallington version and the earlier easel painting) is a landmark in the depiction of industrial Britain. Unlike some contemporaries who romanticized or moralized such scenes, Scott's approach is often more direct and observational, though still imbued with a sense of the epic scale of industrial change. He sought to capture the "brawny, rude, and swart" character of the industrial workers, as he described them. This interest in modern life subjects connects him to broader trends in 19th-century art, seen in the work of French Realists like Gustave Courbet or Jean-François Millet, though Scott's approach remained distinctly British.

Scott was also a skilled etcher, producing numerous prints throughout his career. His etchings often display a freedom and expressiveness that complements his more formal paintings. He also engaged with decorative art, designing stained glass and contributing to the broader interest in applied arts fostered by figures like William Morris and the Arts and Crafts Movement. His designs for the windows of the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert Museum) are an example of this aspect of his work.

Controversies and Critical Reception

William Bell Scott's place in art history has been subject to varied interpretations. During his lifetime, he achieved a degree of recognition as both a painter and a poet. His educational work in Newcastle was undeniably impactful. However, his artistic output was sometimes criticized for a certain dryness or lack of technical finesse compared to the leading academic painters of the day, such as Frederic Leighton or Lawrence Alma-Tadema, or even the more virtuosic Pre-Raphaelites like Millais.

The posthumous publication of his Autobiographical Notes significantly colored his reception. The perceived bitterness and inaccuracies in his accounts of figures like Rossetti led to a backlash, with critics like Algernon Charles Swinburne (initially a friend) and William Michael Rossetti vehemently challenging his narratives. This controversy has, at times, overshadowed a balanced assessment of his artistic and literary merits. Some viewed him as an embittered figure, jealous of the greater fame of some of his contemporaries.

However, in more recent times, art historians have sought to re-evaluate Scott's contributions more objectively. His pioneering role in depicting industrial subjects is increasingly recognized. The Wallington Hall murals are acknowledged as a significant achievement in Victorian public art. His poetry, though not widely read today, is seen as an interesting example of Victorian intellectual verse. His association with the Pre-Raphaelites provides a valuable perspective on the movement from a close, if sometimes critical, observer.

His relationship with Richard Dadd and other "fairy painters" or members of "The Clique" (such as Augustus Egg, William Powell Frith, and Henry Nelson O'Neil) before his deeper PRB involvement, also points to his engagement with alternative artistic currents that sought to break from strict academicism, even if their aims differed from the PRB. Scott's interest in the "Grimaldi Circle," a loose association of artists who, like him, were sometimes at odds with the Royal Academy, further underscores his independent streak.

Legacy and Conclusion

William Bell Scott died at Penkill Castle on November 22, 1890. He was buried in the churchyard at Old Dailly, near Penkill. His legacy is that of a versatile and industrious figure who made notable contributions across several fields. As an artist, he produced a substantial body of work that includes historical paintings, industrial scenes, landscapes, portraits, and decorative designs. His Wallington Hall murals and Iron and Coal remain his best-known visual achievements.

As a poet and writer, he engaged with the intellectual and literary currents of his time, producing poetry of substance and critical works that shed light on his contemporaries and predecessors. As an educator, he played a crucial role in the development of art education in the North of England, influencing a generation of students.

While his reputation may have been complicated by the controversies surrounding his memoirs and a perception of a somewhat abrasive personality, William Bell Scott remains an important figure for understanding the multifaceted nature of Victorian art and culture. He was a man of strong convictions, diverse talents, and significant connections, whose life and work offer a compelling window into a transformative period in British history. His friendships with Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Holman Hunt, and his interactions with figures like John Ruskin, Ford Madox Brown, Edward Burne-Jones, and even the American expatriate James McNeill Whistler, place him firmly within the vibrant and often contentious art world of the 19th century. His story is a reminder that artistic legacies are often complex, shaped by personal relationships, critical fortunes, and the evolving perspectives of history.