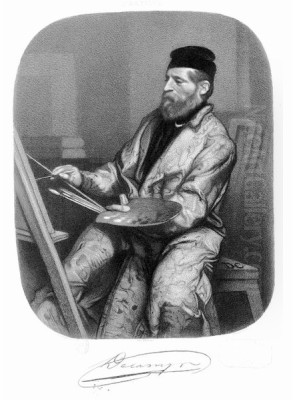

Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps stands as a significant figure in the landscape of 19th-century French art. Born in Paris on March 3, 1803, he emerged as a key proponent of Romanticism and, more distinctively, as one of the earliest and most influential pioneers of Orientalism in painting. His work, characterized by its vibrant depiction of Eastern life, dramatic use of light and shadow, and robust technique, captivated audiences and challenged the artistic conventions of his time. Decamps carved a unique path, leaving behind a legacy that resonated with contemporaries and subsequent generations of artists. His life, marked by travel, keen observation, and a somewhat unconventional spirit, informed an artistic output that remains compelling for its energy and authenticity.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Decamps's origins trace back to a family from Picardy, though he was born in the bustling heart of Paris. A formative part of his childhood, however, was spent away from the city. He was sent to the countryside in Picardy, living among the rural population. This period seems to have been crucial in shaping his character and perhaps his artistic inclinations. Immersed in a life close to nature, engaging in activities like hunting and exploring alongside peasant children, he developed a deep appreciation for the natural world and a certain rugged independence. This experience likely fostered an observational acuity and a spirit of adventure that would later manifest in his travels and art.

His formal artistic training began under the guidance of Étienne Bouhot, a painter known for architectural views. Later, he studied with Abel de Pujol, a respected Neoclassical painter who had himself been a student of the great Jacques-Louis David. While Decamps absorbed technical skills from these masters, his temperament and artistic vision soon diverged significantly from the prevailing Neoclassical ideals. The structured compositions and historical or mythological themes favored by artists like de Pujol did not fully align with Decamps's burgeoning interest in genre scenes, animal studies, and a more dynamic, less idealized representation of reality. His early works already hinted at a unique sensibility, one drawn to texture, strong contrasts, and subjects imbued with character and narrative potential.

The Journey East: Embracing Orientalism

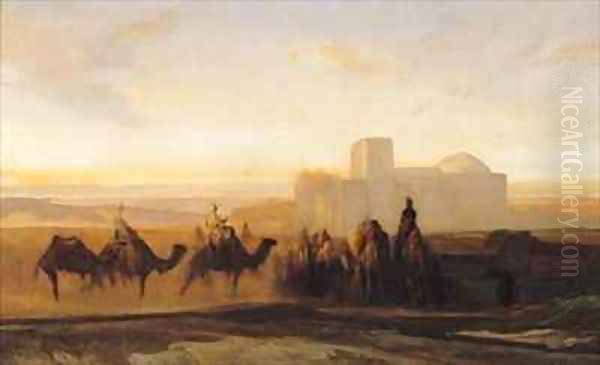

The defining turn in Decamps's career came with his travels to the East. Around 1827-1828, he journeyed through Greece, Turkey (visiting Constantinople and Smyrna in Asia Minor), and possibly other parts of the Levant and North Africa. This was a period when the "Orient"—a term then encompassing the Near East, Middle East, and North Africa—held a powerful allure for European artists and writers, fueled by colonial expansion, travel literature, and a Romantic fascination with the exotic and the unfamiliar. Decamps, however, was among the very first French painters to experience these regions firsthand and translate his observations directly onto canvas with such vigor.

Unlike the often imagined or highly stylized Oriental scenes produced by some predecessors or contemporaries, Decamps sought a more authentic portrayal. His travels provided him with a wealth of sketches, studies, and memories of the landscapes, architecture, people, customs, and light of the East. He was captivated by the bustling street life, the vibrant markets, the textures of ancient walls, the intensity of the sunlight, and the distinct character of the individuals he encountered. This direct experience infused his Orientalist works with a sense of immediacy and realism that was novel and striking. He wasn't merely painting exotic locales; he was capturing the atmosphere and energy of a world vastly different from his own.

Debut and Recognition: The Paris Salon

Decamps burst onto the Parisian art scene with significant impact at the Salon of 1831. He exhibited several works, including the notable Turkish Patrol (La Patrouille Turque). This painting, depicting Ottoman soldiers on patrol, immediately captured attention with its dramatic chiaroscuro, bold brushwork, and convincing depiction of an Eastern scene. It signaled the arrival of a powerful new voice and a fresh perspective. The work was praised for its originality and energy, distinguishing Decamps from many of his contemporaries.

His success at the Salon established him as a leading figure, often mentioned alongside Eugène Delacroix, another giant of French Romanticism who was also exploring Oriental themes, notably after his own trip to North Africa in 1832. While both artists were drawn to the exotic and employed dramatic techniques, their approaches differed. Decamps often focused on genre scenes, everyday life, and a certain earthy realism, while Delacroix frequently tackled more overtly dramatic historical or literary subjects with a more fluid, painterly style. Nonetheless, Decamps, alongside Delacroix and Horace Vernet, came to be seen as a leader of the modern French school, particularly in breaking away from Neoclassical constraints.

His innovative style, however, sometimes perplexed traditional critics. His use of thick paint (impasto), strong, almost harsh contrasts of light and shadow, and sometimes unconventional compositions did not always align with academic expectations of finish and harmony. Yet, this very boldness was also the source of his power and influence. He demonstrated that subjects previously considered minor or merely picturesque could be rendered with seriousness and artistic force.

Artistic Style and Techniques

Decamps's artistic style is marked by several key characteristics. Foremost among these is his mastery of light and shadow (chiaroscuro). He often employed dramatic contrasts, bathing parts of his scenes in brilliant sunlight while plunging others into deep, resonant shadow. This technique not only created visual excitement but also served to model form, enhance texture, and heighten the emotional impact of his compositions. His use of light was often informed by his observations of the intense Mediterranean and Middle Eastern sun.

Texture was another crucial element of his work. Decamps frequently used thick layers of paint, applied with vigorous brushstrokes or even palette knives, creating a tangible surface quality (impasto). This technique gave his paintings a material presence, effectively rendering the roughness of stone walls, the richness of fabrics, or the texture of animal fur. His innovative use of materials, sometimes including bitumen which unfortunately led to later darkening and cracking in some works, aimed at achieving deep, luminous darks and rich surface effects.

His color palette could range from vibrant and saturated, capturing the brilliance of Eastern textiles or sunlit scenes, to more subdued and earthy tones, particularly in his depictions of landscapes or rustic interiors. He possessed a strong sense of color harmony and contrast, using it to structure his compositions and convey mood.

Compositionally, Decamps favored dynamic arrangements, often employing diagonal lines or asymmetrical layouts to create a sense of movement and energy. He had a talent for capturing telling gestures and expressions, bringing his figures, whether human or animal, to life. His works often possess a strong narrative quality, suggesting a moment captured from a larger story, even in seemingly simple genre scenes.

Subject Matter: Beyond the Orient

While Decamps is most famous for his Orientalist paintings, his artistic interests were remarkably diverse. He applied his distinctive style to a wide range of subjects throughout his career.

Biblical Scenes: Decamps produced a significant number of paintings based on Old Testament stories. Works like Joseph Sold by His Brethren (1838) and Moses Rescued from the Nile (1837) are notable examples. What distinguished these works was his decision to set these ancient narratives within realistic Eastern landscapes and populate them with figures drawn from his observations of contemporary Middle Eastern life. This approach lent the familiar stories a new sense of immediacy and historical grounding, moving away from the idealized, classicizing settings typical of earlier religious art. He treated these subjects with the same attention to light, texture, and atmosphere as his genre scenes.

Historical Paintings: Although less numerous than his Orientalist or Biblical works, Decamps tackled historical subjects as well. His most ambitious work in this genre is arguably The Defeat of the Cimbri (also known as Marius Defeating the Cimbri), exhibited at the Salon of 1834. This large, dramatic canvas depicts a chaotic battle scene between Roman legions and barbarian tribes. It was hailed as a masterpiece of Romantic history painting, showcasing his ability to handle complex compositions, convey intense emotion, and render historical events with visceral power. It is often considered the pinnacle of his achievement in grand-scale painting.

Genre Scenes and Everyday Life: Alongside his Eastern subjects, Decamps painted scenes of French rural life, often drawing on his childhood experiences in Picardy. He depicted peasants, hunters, and village scenes with empathy and a keen eye for detail. These works share the same robust technique and focus on character found in his other paintings.

Animal Studies: Decamps had a particular fondness for animals, especially dogs and monkeys, which he depicted frequently. His animal paintings were not mere anatomical studies but were imbued with personality and often placed within narrative contexts. He captured their movements, textures, and characteristic behaviors with remarkable skill and often a touch of humor.

Satire and Caricature: A less-known but fascinating aspect of Decamps's oeuvre is his satirical work. He produced a series of paintings and prints featuring monkeys dressed as humans, engaged in activities like painting, connoisseurship, or cooking. The Monkey Connoisseurs (or Monkey Painters) is a famous example, humorously critiquing the pretensions of art critics and collectors. These works reveal a witty and observant side to his personality.

Key Masterpieces: A Closer Look

Several works stand out as particularly representative of Decamps's talent and contribution:

Turkish Patrol (c. 1830-31): As mentioned, this was his breakthrough work. Its dramatic lighting, capturing the figures emerging from deep shadow into moonlight or lamplight, combined with the exotic subject matter and vigorous execution, established his reputation. It exemplifies his early mastery of Orientalist themes and Romantic effects.

The Defeat of the Cimbri (1833-34): This monumental history painting showcases Decamps's ambition and skill on a grand scale. The swirling chaos of battle, the dynamic composition, and the raw energy conveyed make it a powerful example of French Romantic history painting, rivaling works by Delacroix in its intensity.

Moses Rescued from the Nile (1837) and Joseph Sold by His Brethren (1838): These works are prime examples of his innovative approach to Biblical subjects. By placing the scenes in authentic-seeming Eastern landscapes, possibly inspired by Egypt or Syria, and using contemporary ethnographic details, he revitalized these ancient stories, making them feel tangible and historically plausible within a Romantic framework.

The Monkey Connoisseurs (c. 1840s): This work, part of his "singerie" series (scenes with monkeys aping human behavior), highlights his humor and satirical edge. It cleverly uses animal allegory to comment on human folly, particularly within the art world, demonstrating his versatility beyond dramatic or exotic themes.

Before a Mosque in Cairo (date uncertain): This title, mentioned in the initial prompt's source text, likely refers to one of his many detailed depictions of street life in the East. Such works typically showcase his skill in rendering architecture, capturing the effects of bright sunlight and deep shade, and populating the scene with characteristic figures, demonstrating his keen observation of daily life.

Relationships and Influence: Decamps and His Contemporaries

Decamps occupied a central position in the Parisian art world of his time. His relationship with Eugène Delacroix was significant; they were often seen as the twin pillars of the new Romantic and Orientalist movements. While they respected each other, there was likely an element of artistic rivalry. Both traveled (Decamps earlier to the East, Delacroix to North Africa), both employed bold color and dynamic compositions, and both challenged academic norms. Their influence on the direction of French painting was immense.

He was also associated with Horace Vernet, another prominent painter known for military scenes and Orientalist subjects, though Vernet's style was generally smoother and more detailed. Decamps's robust naturalism and focus on light and texture set him apart. His teachers, Abel de Pujol and Étienne Bouhot, represent the Neoclassical and topographical traditions he initially learned from but ultimately transcended.

Decamps's impact extended to numerous other artists. His pioneering Orientalism paved the way for later generations of painters who specialized in Eastern subjects, such as Jean-Léon Gérôme, Eugène Fromentin, and Théodore Chassériau, although their styles and approaches evolved. His emphasis on realism and capturing the specific character of a place also resonated with landscape painters, potentially including some associated with the Barbizon School, like Théodore Rousseau or Jean-François Millet, who were similarly dedicated to direct observation of nature and rural life, albeit in a French context. Even artists not directly focused on Orientalism could appreciate his technical innovations in handling paint and light. His work provided a powerful alternative to the polished surfaces and idealized forms of Ingres and the stricter Neoclassical school.

Printmaking and Drawing: A Vital Facet

Beyond his celebrated paintings, Decamps was also a highly accomplished draughtsman and printmaker. His drawings, often executed in charcoal, chalk, or pencil, possess the same energy and keen observation found in his paintings. They served as studies for larger works but are also often powerful artworks in their own right, showcasing his mastery of line, form, and chiaroscuro on paper.

He was particularly adept at lithography, a printmaking technique that gained popularity in the 19th century. His lithographs often reproduced his popular paintings or explored similar themes, including Oriental scenes, animal studies, and satirical subjects. These prints helped to disseminate his imagery to a wider audience and were highly regarded for their technical skill and artistic merit. His graphic work forms an integral part of his overall artistic contribution, demonstrating his versatility across different media.

Later Years and Tragic End

In his later years, Decamps spent considerable time in Fontainebleau, south of Paris, an area famous for its forest, which attracted many artists (including those of the Barbizon School). He continued to paint but perhaps with less frequency or public visibility than in his earlier career. He remained passionate about the outdoors and was an avid sportsman and horse rider, pursuits that connected back to his adventurous spirit and childhood experiences.

His life came to an abrupt and tragic end on August 22, 1860. While hunting in the Forest of Fontainebleau, he suffered a fatal accident, being thrown from his horse. He was only 57 years old. His death cut short the career of one of France's most original and influential painters of the Romantic era.

Legacy and Collections

Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps left an indelible mark on French art. He was a foundational figure in the development of Orientalism, bringing a new level of authenticity and painterly vigor to the depiction of Eastern subjects. His bold use of light, color, and texture influenced countless artists and contributed significantly to the broader shift away from Neoclassicism towards Romanticism and, eventually, Realism.

His diverse subject matter, ranging from the exotic East to Biblical narratives, historical dramas, intimate genre scenes, and witty satire, showcases a remarkable breadth of vision. He demonstrated that artistic power could be found in the faithful observation of the world, whether in the bustling streets of Smyrna or the quiet countryside of Picardy.

Today, Decamps's works are held in major museum collections around the world. The Musée du Louvre and the Musée d'Orsay in Paris house significant examples of his paintings and drawings. The Wallace Collection in London holds several important works, including key Orientalist and Biblical scenes. Other museums in France, Europe, and North America also feature his art, ensuring that his unique contribution to 19th-century painting continues to be studied and appreciated.

Decamps in Context: Romanticism and Beyond

Placing Decamps within the broader context of art history highlights his role as a quintessential Romantic artist, yet one with a strong grounding in observation that anticipates later Realist tendencies. Like fellow Romantics such as Géricault and Delacroix, he embraced emotion, drama, individualism, and a fascination with the exotic or untamed. His technique, with its emphasis on visible brushwork and dramatic contrasts, aligns perfectly with Romantic aesthetics.

However, his commitment to depicting what he saw, particularly during his travels, lends his work a documentary quality that distinguishes him. His Orientalism, while filtered through a European lens, aimed for a degree of ethnographic accuracy that was novel for its time. This blend of Romantic sensibility and observational realism makes his work particularly compelling. He bridged the gap between the imagined exoticism of earlier periods and the more detailed, sometimes almost photographic, Orientalism of later artists like Gérôme. Decamps remains a pivotal figure, embodying the energy, curiosity, and artistic innovation of his era.