Introduction: The Divine Artist

Michelangelo Buonarroti stands as a colossus in the annals of art history, a figure whose name is synonymous with the zenith of the Italian Renaissance. Born Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni, he was a polymath whose genius encompassed sculpture, painting, architecture, and poetry. His long and immensely productive life resulted in works that continue to inspire awe and define our understanding of artistic potential. Revered even in his own time as "Il Divino" (The Divine One), Michelangelo's creations possess a power, an emotional depth, and a technical mastery that set him apart. His influence permeated the art of his contemporaries and shaped the course of Western art for centuries to come, leaving an indelible mark on the cultural landscape of Europe and the world.

Early Life and Florentine Foundations

Michelangelo was born on March 6, 1475, in the small town of Caprese, near Arezzo in Tuscany. His family, the Buonarroti Simoni, belonged to the Florentine patriciate but had seen their fortunes decline. His father, Ludovico, served briefly as the judicial administrator in Caprese before returning the family to Florence. Michelangelo's mother, Francesca di Neri di Miniato del Sera, passed away when he was just six years old. Despite his father's initial opposition, rooted in the belief that art was beneath their social standing, young Michelangelo displayed an undeniable passion and talent for drawing and sculpture.

At the age of 13, around 1488, Michelangelo was apprenticed to Domenico Ghirlandaio, one of Florence's leading painters, renowned for his fresco cycles. Under Ghirlandaio, Michelangelo learned the demanding techniques of fresco painting, which would prove crucial later in his career. However, his true inclination lay towards sculpture. His exceptional abilities soon caught the attention of Lorenzo de' Medici, known as "il Magnifico," the de facto ruler of Florence and a great patron of the arts.

Lorenzo invited the young artist into his household and the Medici sculpture garden near the Convent of San Marco. There, Michelangelo studied under Bertoldo di Giovanni, a former pupil of the great Donatello, and gained exposure to Lorenzo's magnificent collection of ancient Roman sculptures. This period was formative, immersing him in the humanist philosophy and Neoplatonic ideas circulating within Lorenzo's circle, which included intellectuals like Marsilio Ficino and Angelo Poliziano. This environment fostered his appreciation for classical forms and the expressive potential of the human figure.

The Emergence of a Master: Early Sculptures

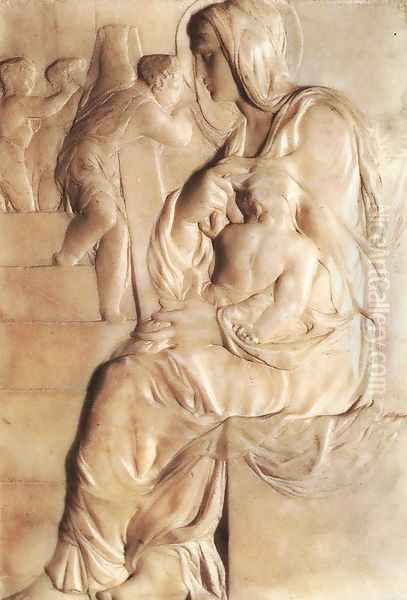

Michelangelo's earliest surviving works demonstrate his precocious talent and rapid absorption of classical principles. Around 1490-1492, he carved two reliefs while under Medici patronage: the Madonna of the Stairs, showing Donatello's influence in its delicate rilievo schiacciato (flattened relief), and the Battle of the Centaurs, a dynamic and complex composition inspired by classical sarcophagi, showcasing his early mastery of the nude figure in motion.

Lorenzo de' Medici's death in 1492 marked a period of uncertainty. After a brief return to his father's house, Michelangelo carved a wooden Crucifix for the prior of Santo Spirito, allegedly in exchange for permission to study anatomy through the dissection of corpses from the church's hospital – an invaluable, albeit clandestine, practice for understanding the human form. Political turmoil, including the rise of the fervent preacher Girolamo Savonarola and the expulsion of the Medici, led Michelangelo to leave Florence, first for Venice, then Bologna.

In Bologna, he contributed three small figures to complete the elaborate Shrine of St. Dominic (Arca di San Domenico) begun by Nicola Pisano centuries earlier. These figures, though small, already hint at the monumental power characteristic of his later work. It was during this period that an anecdote arose concerning a Sleeping Cupid sculpture he created. Some accounts suggest he artificially aged it and sold it as an antique, a ruse that, when discovered, paradoxically enhanced his reputation by demonstrating his ability to rival the ancients.

First Roman Period: The Pietà and Bacchus

In 1496, Michelangelo moved to Rome, drawn by the prospect of greater opportunities. Cardinal Raffaele Riario, impressed by the Sleeping Cupid story (or perhaps the sculpture itself), commissioned a Bacchus. This statue, now in the Bargello Museum in Florence, depicts the god of wine in a tipsy, unsteady pose, a remarkably naturalistic and psychologically nuanced portrayal that broke from purely idealized representations.

His true breakthrough in Rome came with the commission for the Pietà, completed around 1498-1499 for the French Cardinal Jean de Bilhères-Lagraulas, intended for a chapel in St. Peter's Basilica. Carved from a single block of Carrara marble, the Pietà depicts the Virgin Mary cradling the dead body of Christ. The work is celebrated for its technical brilliance, the intricate rendering of drapery, the youthful, serene beauty of Mary, and the profound pathos of the scene. It was the only work Michelangelo ever signed – legend has it, after overhearing pilgrims attribute it to another sculptor. The Pietà established the young artist, still in his early twenties, as a leading sculptor of his time.

Florence and the Colossus: David

Michelangelo returned to Florence around 1501, his reputation secured. The political climate had shifted again with the establishment of a new Republic. The Operai (Cathedral Works committee) offered him a challenging commission: to carve a monumental statue from a huge block of Carrara marble that had lain neglected for decades, previously worked on and abandoned by Agostino di Duccio and Antonio Rossellino. This block, known as "the Giant," was tall and shallow, presenting significant technical difficulties.

Over the next three years (1501-1504), Michelangelo masterfully transformed the flawed block into his iconic David. Departing from traditional representations that showed David after his victory over Goliath, Michelangelo depicted him before the battle, tense, watchful, and psychologically charged. The colossal nude figure, over 17 feet tall, became a symbol of Florentine liberty and defiance. Its anatomical precision, classical contrapposto, and intense gaze (terribilità) were revolutionary. Initially intended for the Florence Cathedral's buttress, its perceived perfection led a committee (including artists like Leonardo da Vinci and Sandro Botticelli) to place it in the politically significant Piazza della Signoria, outside the Palazzo Vecchio, the seat of government.

During this Florentine period, Michelangelo also worked on other significant pieces, including the Pitti Tondo and the Taddei Tondo (unfinished marble reliefs of the Madonna and Child) and the Bruges Madonna, a poignant marble sculpture exported to Flanders. He also received a prestigious commission, alongside Leonardo da Vinci, to paint battle frescoes in the Salone dei Cinquecento (Hall of Five Hundred) in the Palazzo Vecchio. Michelangelo began cartoons for his Battle of Cascina, while Leonardo worked on the Battle of Anghiari. Neither fresco was completed, but the cartoons, particularly Michelangelo's dynamic study of nude soldiers, were highly influential, studied by artists like Raphael and Benvenuto Cellini.

The Summons of Julius II: The Sistine Ceiling

In 1505, Michelangelo's burgeoning fame led Pope Julius II to summon him back to Rome. Julius, an ambitious patron known for his military prowess and grand artistic projects, initially commissioned Michelangelo to design and sculpt his tomb. The original plan was staggeringly complex, involving over 40 life-sized statues, intended for St. Peter's Basilica. Michelangelo spent months in Carrara selecting marble. However, Julius soon diverted funds and attention towards Bramante's project for rebuilding St. Peter's, and the tomb project was scaled back, becoming a source of immense frustration and obligation for Michelangelo for the next four decades.

Instead, in 1508, Julius II offered Michelangelo a different, perhaps even more daunting task: to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. Michelangelo initially resisted, protesting that he was a sculptor, not a painter, and even suspecting rivals like the architect Donato Bramante of suggesting him for the commission in the hope he would fail. Despite his reluctance, he accepted the challenge.

Over four years (1508-1512), working under arduous conditions on specially designed scaffolding, Michelangelo painted over 5,000 square feet of ceiling fresco. He dismissed his initial assistants, preferring to work largely alone. The vast scheme depicts nine scenes from the Book of Genesis, from the Creation of the World to the Drunkenness of Noah, flanked by monumental figures of Prophets and Sibyls, the Ancestors of Christ, and nude youths (Ignudi). The central panels, including the iconic Creation of Adam, The Deluge, and The Fall and Expulsion from Garden of Eden, are masterpieces of composition, anatomical rendering, and dramatic narrative. The Sistine Ceiling transformed Western painting, showcasing a new level of dynamism, emotional intensity, and heroic scale. It stands as one of the supreme achievements of human artistry.

The Tomb of Julius II and the Medici Chapel

Following the completion of the Sistine Ceiling and the death of Julius II in 1513, the tomb project resurfaced, albeit in drastically reduced forms negotiated through successive contracts. Michelangelo worked intermittently on sculptures for the tomb over the next thirty years. The final version, completed in 1545 and installed in the Church of San Pietro in Vincoli (St. Peter in Chains) in Rome, is dominated by the powerful central figure of Moses. Other figures originally intended for the tomb, such as the Rebellious Slave and the Dying Slave (now in the Louvre) and the four unfinished Florentine Slaves (Accademia, Florence), attest to the grandeur of the initial concept and Michelangelo's evolving style, particularly his exploration of the non-finito (unfinished) aesthetic.

Meanwhile, political changes brought the Medici family back to power in Florence, with two members becoming popes: Leo X (Giovanni de' Medici) and Clement VII (Giulio de' Medici). From the 1510s through the early 1530s, Michelangelo spent significant time in Florence working on Medici commissions, primarily at the Basilica of San Lorenzo. He designed a magnificent façade for the church, a project ultimately abandoned due to funding issues, much to his disappointment.

His major undertaking during this period was the New Sacristy, or Medici Chapel, designed as a mausoleum for members of the Medici family. Michelangelo conceived the space as an integrated work of architecture and sculpture. He designed the chapel's interior and created monumental tombs for Lorenzo de' Medici, Duke of Urbino, and Giuliano de' Medici, Duke of Nemours. Each tomb features an idealized portrait statue of the deceased above allegorical figures representing times of day: Dusk and Dawn below Lorenzo, and Night and Day below Giuliano. These sculptures are renowned for their complex poses, psychological depth, and powerful musculature. He also began a Medici Madonna for the chapel. Work was interrupted by political upheaval, including the Sack of Rome (1527) and the brief restoration of the Florentine Republic (1527-1530), during which Michelangelo served as governor of fortifications.

Return to Rome: The Last Judgment and Architecture

In 1534, Michelangelo left Florence for the last time and settled permanently in Rome. Pope Clement VII, shortly before his death, commissioned him to paint the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel. The project was confirmed by Clement's successor, Paul III Farnese. Between 1536 and 1541, Michelangelo executed The Last Judgment, a vast and terrifying fresco depicting the Second Coming of Christ and the fate of souls.

This work differed dramatically in style and mood from the earlier ceiling. It reflects the turbulent religious climate of the Counter-Reformation. Christ is shown as a stern judge, surrounded by a swirling vortex of saints, angels, and the damned. The overwhelming number of nude figures, their muscularity, and the raw emotional power of the scene caused immediate controversy. Critics, including figures within the Church like Cardinal Carafa (later Pope Paul IV) and Master of Ceremonies Biagio da Cesena (whom Michelangelo famously depicted in Hell with donkey ears), condemned the work as indecent for its prominent display of nudity in such a sacred space. Years later, after Michelangelo's death, Pope Pius IV ordered the artist Daniele da Volterra to paint draperies over many of the figures, earning him the nickname "Il Braghettone" (the breeches-maker).

In his later years, Michelangelo increasingly focused on architecture. In 1546, he was appointed chief architect of St. Peter's Basilica, succeeding Antonio da Sangallo the Younger. He returned to Bramante's original Greek-cross plan but simplified and strengthened the design, focusing particularly on the massive dome. Although the dome was completed after his death (by Giacomo della Porta with modifications), its soaring profile remains largely true to Michelangelo's vision and stands as a landmark of Rome.

Other significant architectural projects included the redesign of the Capitoline Hill (Piazza del Campidoglio), creating a harmonious trapezoidal piazza flanked by remodeled and new palaces (Palazzo Senatorio, Palazzo dei Conservatori, Palazzo Nuovo), unified by a distinctive giant order of pilasters. He also oversaw the completion of the Palazzo Farnese. His final paintings were two frescoes for the Pauline Chapel in the Vatican: The Conversion of Saul and The Crucifixion of St. Peter (c. 1542-1550).

Relationships, Rivalries, and Personality

Michelangelo's life was marked by intense relationships and notable rivalries. His competition with Leonardo da Vinci was legendary, highlighted by the aborted Palazzo Vecchio fresco commissions. While respecting Leonardo's genius, Michelangelo reportedly harbored jealousy and maintained a critical stance towards his elder contemporary's more scientific and sfumato-driven approach, contrasting it with his own emphasis on disegno (drawing and design) and sculptural form.

His relationship with Raphael Sanzio was also complex. Raphael, younger and more socially adept, rapidly absorbed influences from both Leonardo and Michelangelo, achieving immense success in Rome. While some accounts suggest professional jealousy and friction, particularly concerning papal favor, Raphael clearly admired Michelangelo's work, as evidenced in his own paintings like the Fire in the Borgo. The architect Donato Bramante was a more direct rival, particularly regarding the St. Peter's commission and possibly the Sistine Ceiling assignment.

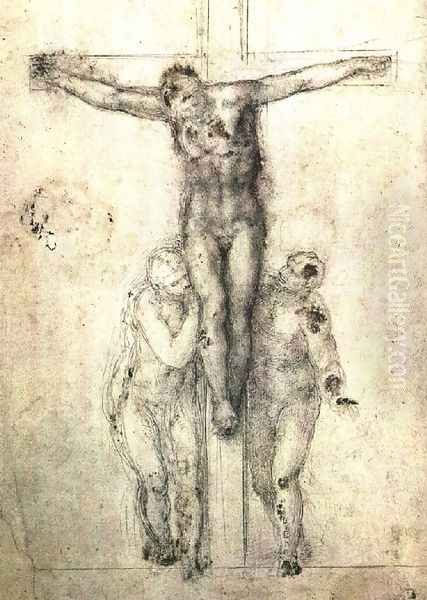

Michelangelo cultivated deep, albeit complex, friendships. His most profound connections seem to have been with young nobleman Tommaso de' Cavalieri, to whom he addressed passionate poems and presented exquisite drawings, suggesting a deep, possibly romantic, platonic love. He also shared a close spiritual friendship with the noblewoman and poet Vittoria Colonna, Marchesa of Pescara. Their correspondence reveals shared religious piety and intellectual companionship.

Michelangelo was known for his difficult, solitary, and often melancholic temperament. He was fiercely protective of his work and independence, leading to clashes with powerful patrons like Julius II. He lived frugally despite his fame and wealth. His biographer and friend, Giorgio Vasari, portrayed him as a divine genius but also hinted at his irascibility and obsessive dedication. Anecdotes abound, such as the story of his nose being broken in a youthful fight with fellow sculptor Pietro Torrigiano, or his supposed hitting of the Moses statue, demanding it speak. These stories contribute to the image of a passionate, driven, and sometimes tormented artist.

Artistic Style, Philosophy, and the Non-Finito

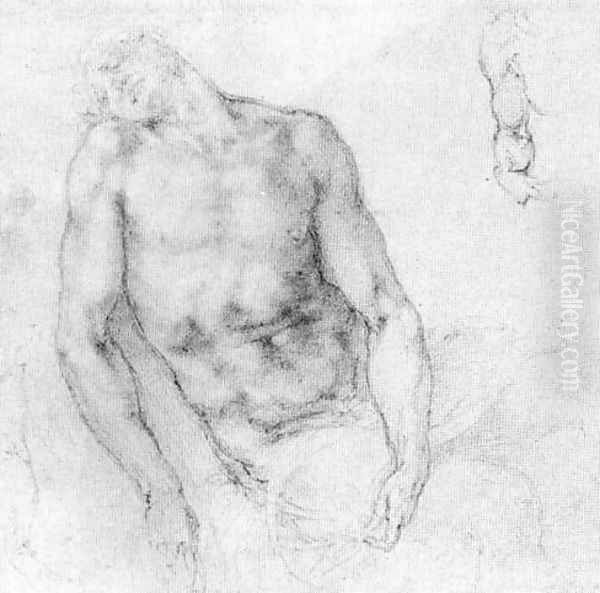

Michelangelo's art is characterized by its terribilità – a term used by contemporaries to describe the awesome power, emotional intensity, and sublime grandeur of his work. His primary focus was the human figure, particularly the male nude, which he saw as the ultimate vehicle for expressing complex emotions and spiritual ideas. His deep understanding of human anatomy, likely enhanced by dissection, allowed him to depict the body with unparalleled accuracy and expressive force.

His approach was fundamentally sculptural, even in painting and architecture. He spoke of "liberating" the figure trapped within the block of marble. This concept aligns with Neoplatonic philosophy, influential in Lorenzo de' Medici's circle, which viewed physical beauty as a reflection of divine beauty. Michelangelo's art often strives to transcend the material and reach towards the spiritual.

A recurring feature in his work, particularly in sculpture, is the non-finito, or unfinished state. Works like the Florentine Slaves, the Taddei Tondo, and his late Pietàs show figures partially emerging from rough-hewn stone. Whether this was always intentional (as an aesthetic choice suggesting struggle or the process of becoming) or often the result of external factors (changing commissions, time constraints, dissatisfaction) remains a subject of debate among art historians. Regardless, the non-finito adds a layer of expressive power and modernity to his work. His poetry, primarily sonnets and madrigals, further reveals his complex thoughts on art, love, faith, and mortality.

Later Years, Death, and Final Works

Michelangelo remained artistically active into his late eighties. His final sculptures explore the Pietà theme with profound spiritual intensity and formal experimentation. The Florentine Pietà (also known as The Deposition, c. 1547-1555), intended for his own tomb, includes a self-portrait as Nicodemus supporting Christ. He famously damaged this work in frustration before abandoning it (it was later partially restored by Tiberio Calcagni).

His last sculpture, the Rondanini Pietà, worked on from around 1552 until the final days of his life, is a hauntingly ethereal piece. The elongated, dematerialized figures of Christ and Mary seem almost fused, conveying a sense of spiritual release and profound sorrow. It stands as a testament to his enduring creativity and evolving spirituality.

Michelangelo died in his home in Rome on February 18, 1564, just weeks before his 89th birthday. He remained lucid until the end, attended by friends including Daniele da Volterra and Tommaso de' Cavalieri. While Pope Pius IV intended for him to be buried in St. Peter's, Michelangelo had expressed a desire to be buried in Florence. His nephew, Leonardo Buonarroti, secretly transported the body back to their native city. Michelangelo was given a magnificent state funeral and interred in the Basilica di Santa Croce, where a grand tomb designed by Giorgio Vasari was erected in his honor.

Legacy: The Measure of Genius

Michelangelo's impact on Western art is immeasurable. Along with Leonardo da Vinci and Raphael, he represents the pinnacle of the High Renaissance. His work, however, also pushed beyond its boundaries, influencing the development of Mannerism with its elongated forms, complex poses, and heightened emotionalism (seen in artists like Pontormo and Bronzino). His dynamic compositions and dramatic intensity prefigured the Baroque era, profoundly influencing sculptors like Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

His mastery across sculpture, painting, and architecture set a new standard for artistic ambition and achievement. The concept of the artist as a divinely inspired genius owes much to his example and the reverence he commanded. From the heroic ideal of the David to the cosmic drama of the Sistine Chapel, the intimate sorrow of the Pietà, and the soaring grandeur of St. Peter's dome, Michelangelo's creations continue to define the heights of artistic endeavor. He remains not just a historical figure, but a living presence whose works challenge, move, and inspire millions across the globe. His legacy is not merely carved in stone or painted on plaster, but etched into the very fabric of Western culture.