Ambrogio Lorenzetti stands as one of the most innovative and intellectually profound painters of the Italian Trecento. Active primarily in Siena during the first half of the 14th century, he, alongside his brother Pietro Lorenzetti, pushed the boundaries of the Sienese school, moving beyond the elegant lyricism of predecessors like Duccio di Buoninsegna and contemporaries like Simone Martini. Ambrogio's art is characterized by a remarkable naturalism, a sophisticated understanding of spatial representation, and a deep engagement with the social and political ideas of his time, culminating in his masterpieces in the Palazzo Pubblico of Siena.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

The precise birthdate of Ambrogio Lorenzetti remains a subject of scholarly discussion, but it is generally placed between 1285 and 1290. He was born in the vibrant city-republic of Siena, a major artistic and political center in Tuscany, often in rivalry with nearby Florence. His artistic training likely occurred within the Sienese tradition, which, at the turn of the 14th century, was dominated by the legacy of Duccio di Buoninsegna, whose monumental Maestà altarpiece for the Siena Cathedral (completed 1311) set a new standard for devotional painting with its Byzantine grace infused with a burgeoning Gothic naturalism.

While Duccio's influence is discernible in Ambrogio's early works, particularly in the elegance of line and richness of color, Ambrogio also appears to have been keenly aware of developments in Florence. The groundbreaking art of Giotto di Bondone, with its emphasis on human emotion, volumetric figures, and coherent narrative spaces, was revolutionizing painting. Ambrogio is documented as having visited Florence, possibly twice, and this exposure undoubtedly contributed to his distinct artistic voice, which sought to synthesize Sienese decorative beauty with Florentine solidity and psychological depth.

His brother, Pietro Lorenzetti, was also a highly accomplished painter, and the two often worked in close proximity, sometimes even collaborating. While their styles are distinct—Pietro often displaying a more dramatic and emotionally charged approach, Ambrogio a more measured and analytical one—they shared a common interest in exploring naturalistic representation and complex human interactions. Their combined efforts significantly shaped the trajectory of Sienese painting in the decades following Duccio.

The Sienese Context: A Flourishing Artistic Milieu

To understand Ambrogio Lorenzetti's contributions, it's essential to appreciate the rich artistic environment of 14th-century Siena. The city prided itself on its civic identity and its devotion to the Virgin Mary, its patron saint. This civic pride and religious fervor fueled numerous artistic commissions, from grand altarpieces for churches to elaborate frescoes for public buildings.

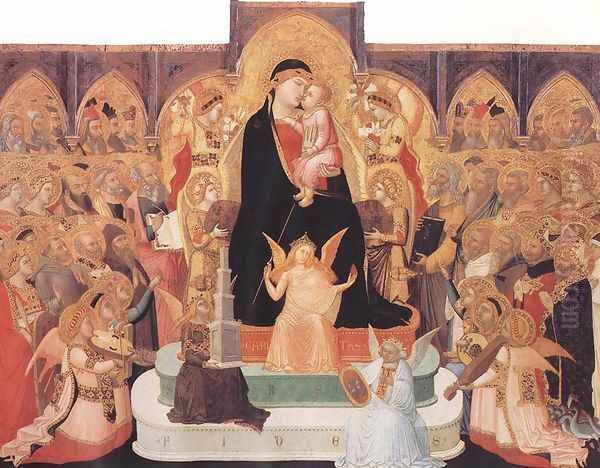

Duccio di Buoninsegna had laid the foundation for the Sienese school's distinctive character. His followers, including Segna di Bonaventura and Ugolino di Nerio, continued his style, emphasizing graceful figures, rich colors, and intricate gold work. However, it was Simone Martini who, alongside the Lorenzetti brothers, became the other towering figure of Sienese painting in this period. Simone Martini, known for his exquisite refinement and courtly elegance, created his own Maestà fresco in the Palazzo Pubblico (1315), a work that showcases the International Gothic style that was becoming popular across Europe. His collaboration with Lippo Memmi on works like the Annunciation with St. Margaret and St. Ansanus (1333) further exemplifies this sophisticated Sienese aesthetic.

The artistic scene was not limited to Siena. In Florence, Giotto's legacy was being carried forward by pupils and followers such as Taddeo Gaddi, who worked on the Baroncelli Chapel frescoes, and Bernardo Daddi, who skillfully blended Giotto's monumentality with Sienese decorative qualities. The exchange of ideas between these two artistic centers, though often marked by political rivalry, was crucial for the development of Italian art. Sculptors like Giovanni Pisano, whose work adorned Siena Cathedral, and later his son Andrea Pisano, active in Florence, also contributed to the era's artistic dynamism with their expressive and classically inspired figures.

Ambrogio Lorenzetti navigated this complex artistic landscape, absorbing influences from various sources while forging a path that was uniquely his own. He was less inclined towards the ethereal grace of Simone Martini and more towards a robust, observational naturalism that found its roots in Giotto but was filtered through a Sienese sensibility.

Ambrogio's Artistic Development and Key Early Works

Ambrogio Lorenzetti is first documented as a painter in 1319. One of his earliest attributed works, the Vico l'Abate Madonna (or Madonna di Vico l'Abate), dated to that year and now in the Museo di San Casciano, already reveals his burgeoning talent. While it retains some Byzantine conventions in the hierarchical arrangement and the golden background, the Virgin's face shows a new softness and three-dimensionality, and the Christ Child appears more naturalistic and engaged with his mother than in earlier Sienese depictions. This work demonstrates Ambrogio's early interest in conveying a sense of physical presence and tender human connection.

Throughout the 1320s and early 1330s, Ambrogio undertook various commissions, including panel paintings and frescoes. His Madonna and Child from the Church of Sant'Eugenio (now in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), likely from the 1320s, shows a further development in naturalism. The figures have a greater sense of volume, and the interaction between mother and child is more intimate and playful.

His visits to Florence during this period would have exposed him more directly to the work of Giotto and his followers. This is evident in his increasing command of depicting three-dimensional space and his ability to render figures with a convincing sense of weight and anatomical structure. He was not merely imitating Florentine models but integrating their lessons into his own evolving Sienese style. Works like the St. Nicholas of Bari Giving Alms (c. 1330-1335, Uffizi Gallery, Florence) showcase his narrative skill and his ability to create lively, populated scenes with a clear sense of spatial depth.

The Palazzo Pubblico Frescoes: A Monumental Achievement

Ambrogio Lorenzetti's most famous and ambitious works are the frescoes in the Sala dei Nove (Hall of the Nine) or Sala della Pace (Hall of Peace) in Siena's Palazzo Pubblico (Town Hall). Commissioned by the Sienese government, the "Nine," who were the city's chief magistrates, these frescoes were painted between 1338 and 1339 (though some sources suggest completion by 1340). They represent one of the most significant cycles of secular painting in medieval art and offer a profound meditation on the nature of governance.

The Commission and its Significance

The commission itself was a testament to Siena's civic humanism and its belief in the power of art to instruct and inspire. The Sala dei Nove was the council room where the city's leaders met, and the frescoes were intended to serve as a constant reminder of their responsibilities and the consequences of their decisions. Unlike the predominantly religious themes that adorned most public spaces, Ambrogio was tasked with creating a complex political allegory. This was a bold and innovative undertaking, reflecting a growing interest in classical philosophy and civic virtue during this period.

The Allegory of Good Government: Vision of a Harmonious State

On the main wall, Ambrogio painted the Allegory of Good Government. This complex composition is dominated by a majestic enthroned figure representing the Common Good or the Commune of Siena, guided by Faith, Hope, and Charity hovering above. He is flanked by personifications of Virtues essential for good governance: Peace, Fortitude, Prudence, Magnanimity, Temperance, and Justice. Justice herself is depicted twice: once enthroned and guided by Wisdom, and again as an executive force, distributing rewards and punishments. Below these figures are Sienese citizens, united in concord, holding a rope that originates from Justice.

The figure of Peace is particularly striking. She reclines languidly on a pile of armor, dressed in white, her pose reminiscent of classical statuary. This serene figure embodies the tranquility and prosperity that result from just rule. The entire allegorical assembly is meticulously organized, with clear iconographic references that would have been understood by the Sienese elite.

The Effects of Good Government in the City and Countryside

To the right of the Allegory of Good Government, Ambrogio painted The Effects of Good Government in the City and The Effects of Good Government in the Countryside. These are panoramic scenes teeming with life and detail, offering a vibrant depiction of a prosperous Sienese society.

In the city scene, Siena itself is depicted with remarkable accuracy, its characteristic architecture—the Duomo, towers, and palazzi—clearly recognizable. The streets are filled with citizens engaged in various activities: merchants conduct business, artisans work in their shops, builders construct new edifices, and a wedding procession winds its way through the town. Dancers gracefully move in a circle in the foreground, symbolizing the joy and harmony of urban life under good rule. The overall impression is one of order, industry, and contentment.

The countryside scene extends this vision of prosperity beyond the city walls. Well-cultivated fields, vineyards, and olive groves stretch into the distance. Peasants are shown tilling the land, harvesting crops, and herding livestock. Nobles ride out to hunt, and travelers move safely along the roads. An allegorical figure of Securitas (Security) hovers above, holding a scroll and a miniature gallows, signifying that peace and justice ensure safe passage and productive labor. This landscape is one of the earliest realistic depictions of a specific Italian countryside in Western art.

The Allegory of Bad Government: A Warning

Opposite the Allegory of Good Government, on the wall that has unfortunately suffered more damage over time, Ambrogio painted The Allegory of Bad Government. Here, the central figure is Tyranny, a demonic, horned figure with fangs, enthroned above a crumbling fortress. He is surrounded by Vices that undermine good governance: Avarice, Pride, Vainglory, Cruelty, Deceit, Fraud, Fury, Division, and War. Justice lies bound and defeated at Tyranny's feet. The composition is a dark mirror image of its virtuous counterpart, serving as a stark warning.

The Effects of Bad Government: Chaos and Despair

Adjacent to the Allegory of Bad Government are The Effects of Bad Government in the City and The Effects of Bad Government in the Countryside. These scenes present a horrifying vision of societal collapse. The city is dilapidated, buildings are in ruins, and violence and fear reign. Soldiers roam the streets, citizens are assaulted, and businesses are shuttered. Justice is ignored, and the city is filled with scenes of murder and destruction.

The countryside under bad government is equally desolate. Fields lie fallow, villages are burned, and the land is ravaged by war and neglect. Fearful peasants flee their homes, and the landscape is barren and dangerous. The figure of Timor (Fear) hovers ominously, emphasizing the insecurity and suffering that result from tyrannical rule.

Artistic Innovation in the Frescoes

The Palazzo Pubblico frescoes are remarkable not only for their complex iconography and political message but also for their artistic innovations. Ambrogio demonstrates an advanced understanding of perspective, creating believable urban and rural spaces. While not a mathematically precise single-point perspective (which would be codified later by artists like Filippo Brunelleschi and theorists like Leon Battista Alberti), his empirical approach to depth and spatial recession was groundbreaking for its time. He skillfully uses architectural elements and diminishing figure sizes to create a convincing illusion of three-dimensionality.

His depiction of figures is equally noteworthy. They are individualized, expressive, and engaged in a wide range of naturalistic activities. Ambrogio's keen observation of daily life infuses these scenes with a sense of immediacy and realism rarely seen before. He masterfully captures the textures of fabrics, the details of architecture, and the nuances of human gesture and expression. This naturalism, combined with the frescoes' intellectual depth, makes them a landmark in the history of art.

Other Notable Works

While the Palazzo Pubblico frescoes are his magnum opus, Ambrogio Lorenzetti produced other significant works throughout his career. His Annunciation of 1344 (Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena) is celebrated for its innovative spatial construction. The scene is set within a meticulously rendered architectural interior, with floor tiles receding in a remarkably accurate, albeit empirical, perspective. The Virgin Mary and the Archangel Gabriel are portrayed with a delicate grace, yet they possess a tangible physical presence. This work is often cited as one of the earliest examples of a consistent, albeit intuitive, use of linear perspective in Italian painting.

He also painted numerous smaller devotional panels, such as the Madonna del Latte (Madonna nursing the Christ Child), a theme that allowed him to explore the tender, human aspect of the Virgin and Child. Examples can be found in the Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena, and the Archbishop's Palace in Siena. These works, often intended for private devotion, showcase his ability to convey deep emotion on an intimate scale.

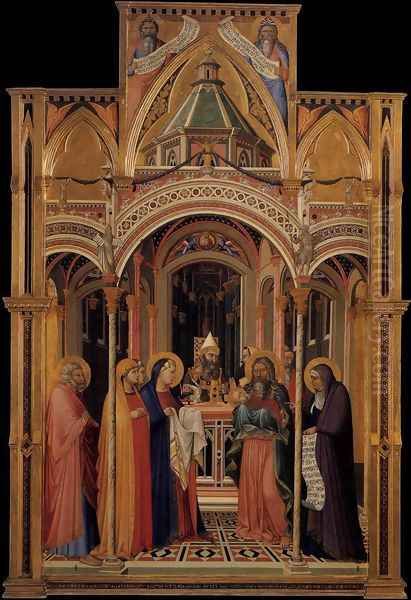

His panel painting Presentation in the Temple (1342, Uffizi Gallery, Florence), originally part of a cycle of altarpieces for Siena Cathedral that also included works by Simone Martini and Pietro Lorenzetti, further demonstrates his narrative clarity and his ability to organize complex figural groups within an architectural setting.

Style and Technique: A Synthesis of Tradition and Innovation

Ambrogio Lorenzetti's artistic style is a complex synthesis of various influences, refined by his own intellectual curiosity and observational skills. He inherited the Sienese love for elegant lines, rich colors, and decorative patterns, evident in the intricate details of fabrics and architectural ornaments in his paintings. However, he tempered this with a robust naturalism and a concern for three-dimensional form that shows an awareness of Giotto's innovations.

His figures are typically more solid and grounded than those of Duccio or Simone Martini. He paid close attention to anatomy and drapery, using light and shadow to model forms and create a sense of volume. His faces are often individualized, conveying a range of emotions and psychological states. This ability to capture human character was a hallmark of his art.

Technically, Ambrogio was a master of both fresco and tempera on panel. His frescoes in the Palazzo Pubblico demonstrate his skill in large-scale composition and his ability to manage complex narratives. His panel paintings, with their refined details and luminous colors, showcase his meticulous craftsmanship. His experiments with perspective, particularly the use of orthogonals (lines receding to a vanishing point, or in his case, a vanishing area) in architectural settings, were pioneering and laid groundwork for later Renaissance artists like Masaccio and Paolo Uccello.

Relationship with Contemporaries

Ambrogio Lorenzetti's career unfolded in dialogue with his contemporaries. His relationship with his brother, Pietro, was particularly close. While they maintained distinct artistic personalities, they likely shared a workshop for a period and influenced each other's development. Both brothers were instrumental in moving Sienese painting towards greater naturalism and emotional expressiveness, building upon Duccio's legacy while responding to Giotto's revolutionary art.

Compared to Simone Martini, Ambrogio was less concerned with courtly elegance and more with conveying the realities of human life and society. While Simone's art often evokes a world of refined chivalry and lyrical beauty, Ambrogio's work is more grounded, often imbued with a sense of civic responsibility and moral purpose. However, both artists contributed to Siena's reputation as a major artistic center.

His engagement with Florentine art, particularly the work of Giotto, was crucial. Ambrogio did not simply copy Giotto but absorbed his principles of spatial coherence, figural solidity, and narrative clarity, adapting them to his own Sienese idiom. He can be seen as a bridge figure, connecting the Sienese tradition with the broader currents of Italian art. Other Sienese painters, like the somewhat enigmatic Barna da Siena, also show the influence of the Lorenzetti brothers' more dramatic and naturalistic style.

The Intellectual Painter: Philosophy and Humanism

Ambrogio Lorenzetti was more than just a skilled craftsman; he was an intellectual painter, deeply engaged with the ideas of his time. The complex allegories in the Palazzo Pubblico frescoes reveal a familiarity with classical philosophy, particularly the political thought of Aristotle (whose works were being rediscovered and discussed) and scholastic thinkers like Thomas Aquinas. The personifications of Virtues and Vices, and the depiction of the ideal state, reflect a sophisticated understanding of contemporary ethical and political theories.

His interest in classical antiquity is also evident in the forms and poses of some of his figures, such as the reclining Peace in the Allegory of Good Government, which echoes ancient Roman sarcophagi or statues. This engagement with classical sources, combined with his observational naturalism, positions Ambrogio as a precursor to the humanist concerns of the Early Renaissance. He was one of the first artists to attempt to translate complex philosophical and political concepts into compelling visual form for a lay audience.

His work suggests a mind that was not only observant of the physical world but also reflective upon its underlying moral and social structures. This intellectual rigor sets him apart from many of his contemporaries and contributes to the enduring power of his art.

The Tragic End: The Black Death

Ambrogio Lorenzetti's productive career was cut tragically short. He, along with his brother Pietro, is believed to have died in 1348, a victim of the Black Death. This devastating pandemic swept across Europe, decimating populations and profoundly impacting society, culture, and art. Siena was particularly hard-hit, losing perhaps half of its inhabitants.

The loss of Ambrogio and Pietro Lorenzetti, along with many other artists and patrons, marked a turning point for Sienese art. The creative momentum of the early 14th century was significantly curtailed. While Sienese painting continued to flourish in the later Trecento with artists like Bartolo di Fredi and Taddeo di Bartolo, the innovative spirit and intellectual depth of Ambrogio Lorenzetti's work remained unparalleled for some time. His death, at the height of his powers, was an immeasurable loss to Italian art.

Legacy and Historical Evaluation

Despite his premature death, Ambrogio Lorenzetti left an indelible mark on the history of art. His Palazzo Pubblico frescoes remain one of the most important monuments of 14th-century Italian painting, celebrated for their artistic innovation, their complex iconography, and their enduring relevance as a commentary on governance. They are a touchstone for understanding the civic humanism of the Italian city-republics.

Art historians recognize Ambrogio as a key figure in the development of naturalism and perspective in European painting. His ability to create believable, populated landscapes and cityscapes, and to depict human figures with psychological insight, was revolutionary for his time. He expanded the thematic range of art, demonstrating that painting could address complex secular and philosophical ideas with the same power and sophistication as religious subjects.

While Giorgio Vasari, the 16th-century biographer of artists, somewhat confused the achievements of Ambrogio with those of Pietro, later scholarship has clarified Ambrogio's distinct contributions and affirmed his status as one of the great masters of the Trecento. His work influenced subsequent generations of Sienese artists and contributed to the broader artistic currents that led to the Renaissance. Artists like Sassetta and Giovanni di Paolo in the 15th century, while developing their own unique styles, still operated within a Sienese tradition shaped by the innovations of Duccio, Simone Martini, and the Lorenzetti brothers.

Modern research continues to explore the nuances of Ambrogio's art, from the technical aspects of his painting to the intellectual sources of his iconography. Exhibitions and scholarly publications have brought his work to a wider audience, highlighting his originality and his importance in the transition from medieval to Renaissance art.

Conclusion

Ambrogio Lorenzetti was a painter of extraordinary talent and intellectual depth. Working within the vibrant artistic milieu of 14th-century Siena, he synthesized the elegance of the Sienese tradition with the groundbreaking naturalism of Florentine art, forging a style that was uniquely his own. His keen observation of the world around him, combined with his sophisticated understanding of philosophical and political ideas, resulted in works of art that are both visually compelling and intellectually stimulating.

His frescoes in the Palazzo Pubblico stand as a timeless testament to the power of art to reflect and shape societal values. Through his innovative use of perspective, his naturalistic depiction of figures and landscapes, and his profound engagement with themes of governance and civic virtue, Ambrogio Lorenzetti secured his place as one of the most important and forward-looking artists of the Italian Trecento, a true master whose work continues to resonate with viewers centuries later. His legacy is not just in the beauty of his paintings, but in the enduring questions they pose about how societies can achieve peace, justice, and prosperity.