Pietro Lorenzetti stands as a pivotal figure in the rich tapestry of fourteenth-century Italian art. Active primarily in Siena between approximately 1306 and 1345, his work embodies the transition from the stylized elegance of Byzantine-influenced art towards a more naturalistic, emotionally resonant, and spatially aware form of painting that anticipated the Renaissance. Working alongside his brother, Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Pietro helped define the Sienese school's unique character, blending local traditions with groundbreaking innovations drawn from contemporaries like Giotto. His legacy is found in powerful frescoes and altarpieces that continue to captivate viewers with their narrative depth and human sensitivity.

Born likely around 1280 in Siena, Pietro emerged into an artistic environment dominated by the legacy of Duccio di Buoninsegna. Siena, a prosperous and fiercely independent city-republic, was a major center for artistic production, rivaling Florence in its cultural achievements. The Sienese school, largely shaped by Duccio, was known for its lyrical lines, rich colors, and decorative beauty, often retaining stronger ties to Byzantine traditions than the more volumetrically focused Florentine school. It was within this vibrant context that Pietro Lorenzetti began his artistic journey, absorbing the prevailing styles while forging his own distinct path.

Early Formation and Influences

The precise details of Pietro Lorenzetti's training remain undocumented, but the influence of Duccio di Buoninsegna is undeniable in his early work. Duccio's monumental Maestà altarpiece, completed for the Siena Cathedral in 1311, set a benchmark for Sienese painting with its complex narrative, elegant figures, and sophisticated use of gold leaf and color. Pietro likely studied Duccio's workshop practices, mastering the techniques of tempera painting on panel and fresco. He absorbed Duccio's emphasis on graceful composition and expressive, albeit stylized, figures.

However, Pietro did not remain solely within the Ducciesque tradition. He was profoundly receptive to the revolutionary developments occurring in Florence and Assisi, particularly the work of Giotto di Bondone. Giotto's emphasis on human drama, psychological depth, and the creation of tangible, three-dimensional space marked a significant departure from earlier styles. Pietro seems to have studied Giotto's frescoes, perhaps directly in Assisi or Padua, internalizing the Florentine master's ability to convey weight, volume, and powerful emotion through gesture and composition.

Another significant influence was the sculptor Giovanni Pisano, who had worked on the facade of the Siena Cathedral. Pisano's dynamic, emotionally charged figures, carved with a dramatic intensity, likely inspired Pietro to imbue his painted figures with greater physical presence and psychological weight than was typical in purely Ducciesque painting. The interaction between painting and sculpture was a vital aspect of artistic development during this period.

Furthermore, Pietro worked concurrently with Simone Martini, another leading Sienese painter who also emerged from Duccio's circle. While Simone developed a more courtly, elegant style often associated with the International Gothic, characterized by flowing lines and aristocratic refinement, he and Pietro shared an interest in narrative and emotional expression. They represent two distinct but complementary facets of the Sienese school's evolution in the early Trecento, sometimes influencing each other in their respective commissions.

Developing a Unique Style: Naturalism and Emotion

Pietro Lorenzetti synthesized these diverse influences into a style uniquely his own. While retaining the Sienese appreciation for color and line inherited from Duccio and Simone Martini, he infused his work with a Giottesque sense of volume, drama, and human feeling. His figures possess a physical solidity and emotional gravity that sets them apart. He excelled at depicting tender interactions, moments of intense grief, and complex narrative scenes with clarity and psychological insight.

A key aspect of Pietro's innovation was his exploration of pictorial space. While not employing the mathematically precise perspective developed during the Quattrocento, he experimented with architectural settings and landscape elements to create a convincing sense of depth. He arranged figures within these settings in ways that suggested real spatial relationships, moving beyond the flatter, more symbolic spaces often seen in earlier Sienese art. This nascent naturalism, combined with his emotional intensity, marks him as a crucial transitional figure.

His use of color was both rich, in the Sienese tradition, and functional, employed to enhance the emotional tone and structure the composition. He could deploy vibrant hues for dramatic effect or utilize more muted palettes to create moments of quiet intimacy. His handling of light and shadow, while not fully developed chiaroscuro, began to model forms and enhance their three-dimensionality, contributing significantly to the naturalistic feel of his work.

Major Works: The Arezzo Polyptych

One of Pietro Lorenzetti's earliest documented and most significant works is the large polyptych painted around 1320 for the high altar of the Pieve di Santa Maria in Arezzo. This multi-paneled altarpiece, featuring the Madonna and Child enthroned with Saints John the Evangelist, Donatus, John the Baptist, and Matthew, demonstrates his early mastery and the confluence of influences shaping his style. The central figures retain a certain Ducciesque elegance and hierarchical solemnity.

However, the Arezzo Polyptych also reveals Pietro's burgeoning interest in volume and naturalism. The Madonna possesses a tangible weight, and the Christ Child appears more convincingly infant-like than many contemporary representations. The saints flanking the throne are rendered with individual characterization. Below, in the predella panels depicting scenes from the lives of the saints and the Virgin, Pietro showcases his narrative skill and his ability to convey emotion through gesture and interaction within simplified but effective spatial settings. This work established his reputation beyond Siena and remains a cornerstone for understanding his early development.

Frescoes in Assisi: Drama and Narrative Power

Pietro Lorenzetti's contributions to the decoration of the Basilica of Saint Francis in Assisi are among his most celebrated achievements. Working in the Lower Church, likely during the 1320s, he painted a series of frescoes depicting the Passion of Christ. This commission placed him in direct dialogue with the earlier works of Cimabue and the monumental narrative cycles by Giotto in the Upper Church and potentially the Lower Church as well.

His Assisi frescoes are characterized by their intense emotionalism and dramatic force. The Crucifixion is a powerful composition, filled with grieving figures whose sorrow is palpable. The Deposition from the Cross is particularly renowned for its raw depiction of grief, as the followers of Christ tenderly remove his body. The figures possess a sculptural quality, their heavy draperies emphasizing their physical presence and emotional weight.

Perhaps the most innovative fresco in the Assisi cycle is the Last Supper. Departing from traditional, more static representations, Pietro sets the scene in a hexagonal upper room, creating a dynamic sense of space. He includes anecdotal details, like a servant scraping leftovers for a dog and cat in the foreground kitchen area, adding a touch of everyday realism that contrasts with the solemnity of the main event. This integration of genre elements within a sacred narrative was highly original for its time and demonstrates Pietro's keen observation of human life. The emotional interactions between Christ and the apostles, particularly the impending betrayal of Judas, are conveyed with subtle intensity.

Sienese Commissions: Mastery in Panel and Fresco

Back in Siena, Pietro continued to receive important commissions. Although less documented than his work in Arezzo and Assisi, fragments and records point to his activity in various Sienese churches. He painted frescoes, now partially preserved, in the Basilica di San Francesco and the Church of Santa Maria dei Servi. These works further demonstrate his ability to adapt his style to the demands of large-scale wall painting, creating compelling narratives within complex architectural spaces.

He also continued to produce exquisite panel paintings. Works like the Madonna and Child with Angels (originally from the church of San Francesco, now in the Uffizi, Florence) show his ability to combine monumental presence with tender emotion. The interaction between mother and child is rendered with warmth and psychological insight, moving beyond purely iconic representation.

The Birth of the Virgin: A Masterpiece of Spatial Innovation

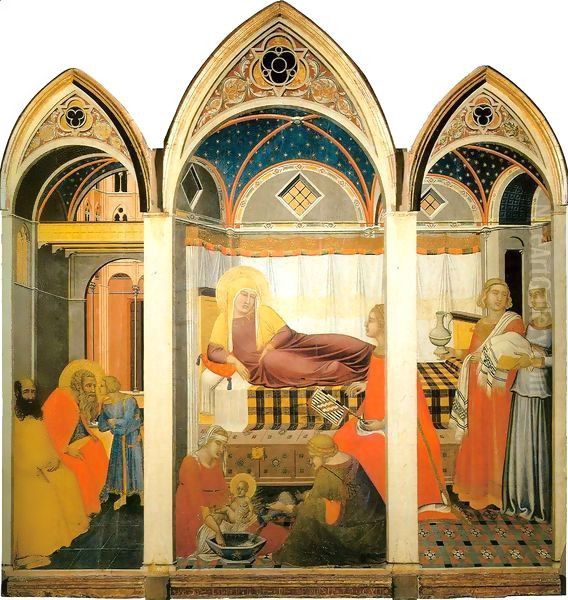

Dated 1342, The Birth of the Virgin is one of Pietro Lorenzetti's last known works and arguably one of his greatest masterpieces. Originally commissioned for the Altar of St. Savinus in Siena Cathedral, it now resides in the Museo dell'Opera del Duomo. This panel is remarkable for its innovative approach to space and narrative. Instead of depicting the scene in an ambiguous or symbolic setting, Pietro places the event within a contemporary Sienese interior, meticulously rendered with architectural details like vaulted ceilings and tiled floors.

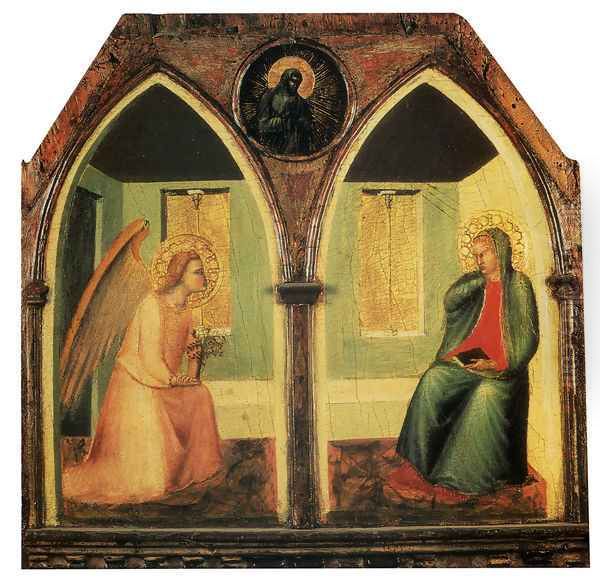

The panel is divided into three sections by painted architectural elements that mimic the frame, creating the illusion that the viewer is looking into three adjacent rooms of a house. In the main central space, Saint Anne reclines on a bed after giving birth, attended by midwives, while in the left chamber, Joachim, Mary's father, anxiously awaits news. This division of space allows for a continuous narrative flow and creates an unprecedented sense of domestic intimacy and realism within a sacred subject. The figures interact naturally within this believable environment, their gestures and expressions conveying the story with quiet dignity and human warmth. The Birth of the Virgin is a landmark in the development of spatial representation in Italian painting, showcasing Pietro's mature style and his forward-looking experimentation. It stands alongside Simone Martini's Annunciation and Duccio's Maestà as one of the great altarpieces created for the Siena Cathedral in this era.

Later Works and the Saint Humility Panels

Among Pietro's later works are panels depicting scenes from the life of the Blessed Humility (Umiliana de' Cerchi), likely part of a dismembered polyptych, now housed in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. These narrative panels, probably dating from the 1330s or early 1340s, showcase his continued skill in storytelling and his ability to render lively details and expressive figures within clearly defined settings. They demonstrate his sustained productivity and artistic vitality in the years leading up to his death.

Other works attributed to his later period, or to his workshop, continue to explore the themes of human emotion and interaction within increasingly sophisticated spatial constructions. Artists like Niccolò di Segna and the Master of the Ovile Madonna show affinities with Pietro's style, suggesting the influence he exerted within the Sienese artistic community.

Collaboration and Context: The Lorenzetti Brothers

Pietro's career is inextricably linked with that of his younger brother, Ambrogio Lorenzetti. While historical sources like Giorgio Vasari confirm their fraternal relationship, and their artistic paths were closely related, they maintained distinct artistic personalities. Ambrogio is perhaps most famous for his allegorical frescoes of Good and Bad Government in Siena's Palazzo Pubblico, which display a keen interest in classical sources, complex symbolism, and detailed observation of contemporary life.

While direct collaboration on specific works is difficult to prove definitively, Pietro and Ambrogio undoubtedly shared workshop space, assistants, and ideas. They both contributed significantly to the shift towards naturalism in Sienese art. Pietro's style is often characterized as being more emotionally intense and dramatic, perhaps more directly influenced by Giotto's pathos, while Ambrogio's work sometimes displays a greater intellectual complexity and a broader range of interests, including landscape and allegory. Together, they represented the pinnacle of Sienese painting in the second quarter of the fourteenth century, building upon Duccio's legacy while pushing artistic boundaries. Other Sienese contemporaries included followers of Duccio like Ugolino di Nerio and Segna di Bonaventura, and Simone Martini's collaborator and brother-in-law, Lippo Memmi.

The Shadow of the Plague

The flourishing artistic scene in Siena, led by figures like the Lorenzetti brothers and Simone Martini, came to an abrupt and tragic halt with the arrival of the Black Death in 1348. This devastating pandemic wiped out a significant portion of Europe's population, and Siena was hit particularly hard. It is widely believed that both Pietro and Ambrogio Lorenzetti perished during the plague outbreak. No documented works by either brother exist after 1348.

The Black Death marked a profound rupture in Sienese society and culture. The loss of its leading artists created a vacuum, and while the Sienese school continued to produce beautiful works in the later fourteenth and fifteenth centuries with artists like Bartolo di Fredi, Taddeo di Bartolo, Sassetta, and Giovanni di Paolo, it arguably never fully regained the innovative momentum and prominence it held during the era of Duccio, Simone Martini, and the Lorenzetti brothers.

Legacy and Art Historical Significance

Pietro Lorenzetti's importance in the history of art lies in his role as a bridge figure. He successfully merged the decorative elegance and spiritual intensity of the Sienese tradition with the new naturalism, spatial awareness, and human drama pioneered by Giotto and Giovanni Pisano. His work demonstrates a profound understanding of human emotion, rendered with a directness and sensitivity that remains compelling.

His experiments with perspective and architectural space, particularly evident in works like the Assisi Last Supper and the Siena Birth of the Virgin, were groundbreaking for their time and anticipated later Renaissance developments. He demonstrated that complex spatial illusions and realistic settings could enhance, rather than detract from, the spiritual power of religious narratives.

Alongside his brother Ambrogio, Pietro Lorenzetti elevated the status of Sienese painting, ensuring its place alongside the Florentine school as a major center of innovation in the Trecento. While sometimes overshadowed in historical narratives by the Florentine giants, his contributions were essential to the broader evolution of Italian art. He influenced subsequent generations of Sienese painters and left behind a body of work characterized by its technical mastery, emotional depth, and narrative power. His paintings offer a window into the spiritual and artistic world of fourteenth-century Siena, capturing moments of profound human feeling within scenes of sacred history. He remains a testament to the creative vitality of Sienese art at its height.