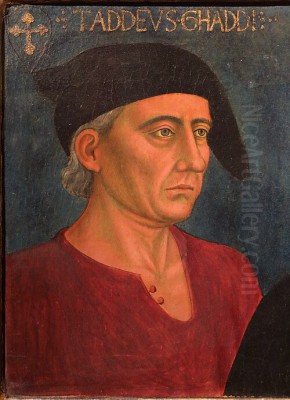

Taddeo Gaddi stands as a pivotal figure in the landscape of early Italian Renaissance art, a painter and architect whose career unfolded in the vibrant artistic crucible of 14th-century Florence. Born into an artistic lineage around the year 1300, he was destined to become one of the most significant and faithful disciples of the revolutionary master Giotto di Bondone. While deeply indebted to Giotto's groundbreaking naturalism and narrative power, Taddeo forged his own distinct artistic identity, characterized by a refined sense of color, an interest in complex spatial arrangements, and a gentle, humanizing approach to sacred themes. His extensive body of work, primarily frescoes and panel paintings, not only continued the Giottesque tradition but also contributed to its evolution, influencing a subsequent generation of artists in Florence and beyond. His death in 1366 marked the end of a prolific career that left an indelible mark on the course of Western art.

Early Life and the Shadow of Giotto

Taddeo Gaddi's entry into the world of art was almost preordained. His father, Gaddo Gaddi, was himself a respected painter and mosaicist active in Florence, providing Taddeo with an early immersion in artistic practice. However, the defining relationship of his formative years was undoubtedly his apprenticeship with Giotto di Bondone. According to the 16th-century biographer Giorgio Vasari, and corroborated by the artist Cennino Cennini in his "Il Libro dell'Arte" (The Craftsman's Handbook), Taddeo spent a remarkable twenty-four years in Giotto's workshop. This extended period, likely beginning around 1313 and lasting until Giotto's death in 1337, suggests a deep bond of trust and a thorough absorption of the master's techniques and artistic vision.

Giotto, a towering figure who had broken decisively with the stylized conventions of Byzantine art, introduced a new era of naturalism, emotional depth, and spatial illusionism. His influence on Taddeo was profound and enduring. In the years following Giotto's passing, Taddeo Gaddi emerged as one of the leading figures, if not the principal heir, to his master's workshop and artistic legacy in Florence. He was entrusted with completing projects Giotto may have left unfinished and became a key transmitter of Giottesque principles to a new generation. The weight of this legacy was significant, and much of Taddeo's early independent work understandably reflects a close adherence to Giotto's style, compositional formulas, and figural types. Artists like Maso di Banco, another of Giotto's brilliant followers, also navigated this influential legacy, each finding unique expressions within the new artistic language Giotto had established.

Developing an Independent Artistic Voice

While Taddeo Gaddi remained a loyal follower of Giotto throughout his career, he was not merely an imitator. Over time, he developed a more personal style that, while rooted in Giotto's innovations, also showcased his own sensibilities and strengths. One of the areas where Taddeo particularly distinguished himself was in his use of color. His palette was often richer, more varied, and applied with a greater subtlety than that of his master. He demonstrated a keen interest in the effects of light and shadow, using them not only to model forms but also to create specific atmospheric and emotional effects. This is particularly evident in his night scenes, such as the "Annunciation to the Shepherds" in the Baroncelli Chapel, where he experimented with artificial light sources to create a dramatic and evocative ambiance, a feature less commonly explored by Giotto himself.

Furthermore, Taddeo often displayed a penchant for more intricate and detailed compositions than Giotto. His narratives could be more densely populated, and he paid considerable attention to architectural settings, sometimes employing more complex, if not always perfectly consistent, perspectival constructions. This interest in architectural detail extended beyond his painted representations, as he was also active as an architect. His figures, while retaining the solidity and presence of Giotto's, often possess a softer, more gentle quality, and his storytelling, though clear and effective, could sometimes lean towards a more descriptive and anecdotal approach compared to Giotto's powerful dramatic concision. These developments show Taddeo engaging with the artistic currents of his time, where contemporaries like Bernardo Daddi were also exploring more lyrical and decorative interpretations of Giotto's heritage.

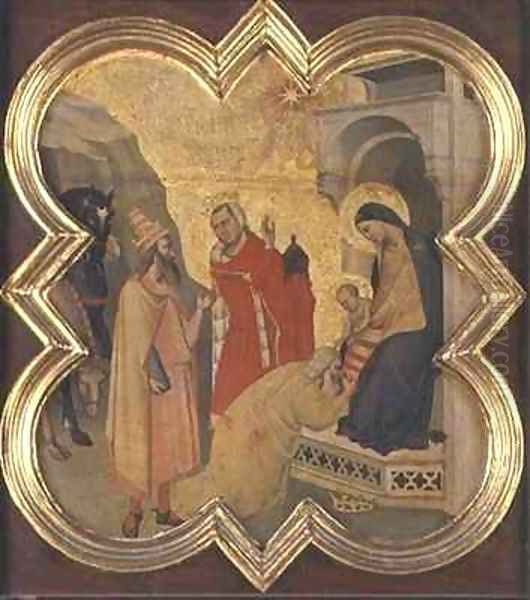

The Baroncelli Chapel: A Masterpiece in Santa Croce

Perhaps Taddeo Gaddi's most celebrated and extensive commission is the fresco cycle depicting scenes from the Life of the Virgin in the Baroncelli Chapel in the Basilica di Santa Croce, Florence. Executed between approximately 1328 and 1338, these frescoes are a testament to his mature artistic abilities and his deep understanding of narrative painting. The chapel, endowed by the wealthy Baroncelli family, provided Taddeo with a prominent canvas to showcase his talents. The cycle unfolds across the chapel walls, narrating key episodes from the Virgin Mary's life, from her early years to her marriage and the events surrounding the birth of Christ.

In these frescoes, Taddeo demonstrates his mastery of Giottesque principles of clear storytelling, volumetric figures, and expressive gestures. Works like "The Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple" and "The Marriage of the Virgin" are notable for their well-organized compositions and the human interactions they portray. However, it is in the "Annunciation to the Shepherds," a scene integrated into the Nativity, that Taddeo's innovative spirit shines most brightly. Here, he daringly depicts a night scene, with the divine light emanating from the angel dramatically illuminating the startled shepherds and their flock. This was a bold experiment in the representation of light and atmosphere for its time and stands as one of the earliest convincing nocturnal scenes in Italian painting. The overall effect of the Baroncelli Chapel frescoes is one of solemn dignity and tender humanity, solidifying Taddeo's reputation as a leading painter in Florence. The Sienese masters, such as Simone Martini and the Lorenzetti brothers, Pietro and Ambrogio, were concurrently exploring different, though equally innovative, paths in narrative and emotional expression, providing a rich counterpoint to Florentine developments.

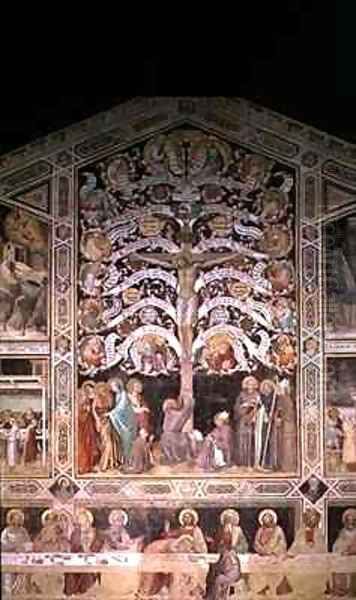

The Refectory of Santa Croce: The "Tree of Life" and "Last Supper"

Beyond the Baroncelli Chapel, Taddeo Gaddi also left a significant mark on another part of the Santa Croce complex: the refectory (dining hall) of the monastery. Here, he painted a monumental fresco ensemble dominated by the "Tree of Life" (L'Albero della Vita), with scenes of the "Last Supper" and other sacred subjects below it. This complex allegorical and narrative program was a common theme for monastic refectories, intended for the contemplation of the friars.

The "Tree of Life" is a complex iconographic image, with Christ crucified on a living tree, its branches bearing roundels with prophets and scenes from Christ's life. At the base of the tree, figures like St. Francis, St. Bonaventure, and other saints are depicted. This work showcases Taddeo's ability to organize a vast and symbolically rich composition. Below this, his depiction of the "Last Supper" is particularly noteworthy. While following the traditional iconography of the scene, Taddeo imbues it with a sense of gravity and individual characterization among the apostles. Judas is typically isolated on the opposite side of the table, a convention Giotto also employed in his Arena Chapel "Last Supper." Taddeo's version is notable for its careful arrangement of figures and the detailed rendering of the setting. These frescoes suffered damage over time, particularly during the devastating Florence flood of 1966, but have since undergone significant restoration, allowing contemporary viewers to appreciate their original grandeur and Taddeo's skill in handling large-scale narrative compositions. Such monumental works were also being undertaken by artists like Andrea Orcagna and his brothers Nardo and Jacopo di Cione in other Florentine churches, reflecting the city's vibrant artistic patronage.

Panel Paintings, Altarpieces, and Wider Influence

While Taddeo Gaddi is renowned for his fresco cycles, he was also a prolific painter of panel paintings, including altarpieces and smaller devotional works. These panels, often executed in tempera and gold leaf, further demonstrate his refined technique and his ability to adapt his style to different formats and purposes. Many of these works are now dispersed in museums and collections worldwide. For instance, a "Madonna and Child" attributed to him, now in the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., showcases his characteristic gentle rendering of figures and his rich use of color.

He is also credited with works such as the "Stefaneschi Triptych" (though this attribution is sometimes debated and also linked to Giotto's workshop or Giotto himself), which was commissioned for St. Peter's Basilica in Rome, indicating the reach of his reputation beyond Florence. An altarpiece for the Pistoia Cathedral is another significant commission mentioned in historical sources. His panel paintings often feature elaborate gold backgrounds and tooling, typical of the Sienese tradition as well, seen in the works of Duccio di Buoninsegna, but Taddeo's figures retain their Florentine solidity. These works, alongside his frescoes, helped to disseminate the Giottesque style, albeit with Taddeo's personal inflections, to a wider audience and to other artistic centers. His influence can be seen in the works of lesser-known contemporaries and followers who adopted elements of his compositions and figural types.

Architectural Endeavors: The Ponte Vecchio and Beyond

Taddeo Gaddi's talents were not confined to painting; he was also recognized as an architect. Giorgio Vasari, in his "Lives of the Artists," credits Taddeo with the design and rebuilding of the Ponte Vecchio, Florence's iconic bridge, after it was destroyed by a flood in 1333. According to Vasari, Taddeo's design, completed around 1345, was innovative for its time, featuring wider arches and a more robust structure, which has allowed it to endure for centuries. While the precise extent of Taddeo's involvement as the sole architect is a subject of some scholarly discussion, as large civic projects often involved multiple consultants and overseers, his association with this major undertaking underscores his reputation as a skilled designer.

His architectural acumen may also have been employed in the design or supervision of other structures, or at least in the architectural elements within his own fresco commissions, which often display a sophisticated understanding of built space. There is also mention of his involvement in the construction of the Campanile (bell tower) of Florence Cathedral, designed by Giotto, after Giotto's death, alongside Francesco Talenti. This dual role as painter and architect was not uncommon in the Renaissance, with figures like Giotto himself and later masters like Brunelleschi and Michelangelo excelling in multiple artistic disciplines. Taddeo's contributions in architecture further highlight his versatility and his significant role in shaping the physical and artistic landscape of 14th-century Florence.

The Gaddi Workshop: Collaboration and Continuation

Like his master Giotto, Taddeo Gaddi maintained an active and productive workshop. This was essential for handling the large-scale fresco commissions and the demand for panel paintings. The workshop system involved apprentices and assistants who learned their craft by participating in various stages of a project, from preparing surfaces and grinding pigments to painting less critical areas under the master's supervision. This collaborative environment ensured the efficient execution of commissions and the transmission of artistic knowledge.

Among Taddeo's most important collaborators and pupils were his own sons, particularly Agnolo Gaddi. Agnolo became a significant painter in his own right, continuing and further developing the Gaddi family's artistic tradition into the late 14th century. He inherited his father's workshop and built upon his style, often displaying an even greater penchant for decorative effects and a more courtly elegance, reflecting the evolving tastes of the period. The collaboration between Taddeo and Agnolo is evident in some later projects, and Agnolo's independent career demonstrates the successful continuation of the Gaddi artistic lineage. Another painter sometimes associated with Taddeo's circle or influence, though perhaps more as a contemporary who shared market space, was Bernardo Daddi. There is even speculation by some scholars about a possible commercial agreement or partnership between Taddeo Gaddi and Bernardo Daddi to manage the Florentine painting market after Giotto's death, though concrete evidence for this remains elusive.

Students and the Spread of Influence

Taddeo Gaddi's role as a teacher extended beyond his own family. As a leading practitioner of the Giottesque style, his workshop would have attracted aspiring artists eager to learn from one of Giotto's closest followers. Cennino Cennini, who himself was a student of Agnolo Gaddi, provides valuable insight into the workshop practices of the time and, by extension, the kind of training Taddeo would have overseen.

Among the artists documented or believed to have been students or significantly influenced by Taddeo Gaddi are Giovanni da Milano and Jacopo di Casentino. Giovanni da Milano, though Lombard by origin, was active in Florence and his work shows a synthesis of Giottesque monumentality, possibly filtered through Taddeo, with a Northern Italianate refinement and attention to detail. Jacopo di Casentino, another Florentine painter, is also considered to have been in Taddeo's circle. According to some sources, Jacopo di Casentino, in turn, became the master of Spinello Aretino, a prolific and important painter active in Tuscany towards the end of the 14th century. This lineage, from Giotto to Taddeo Gaddi, then to Jacopo di Casentino and Spinello Aretino, illustrates the transmission of artistic knowledge and style across generations, with each artist adding their own interpretations and innovations. The influence of Taddeo's workshop thus played a crucial role in shaping the course of Florentine painting in the decades following Giotto's death.

Character, Reputation, and Vasari's Account

Giorgio Vasari's "Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects" remains a foundational, if sometimes embellished, source for information on Renaissance artists, including Taddeo Gaddi. Vasari generally held Taddeo in high regard, praising his loyalty to Giotto and his considerable skill. He recounts anecdotes that paint a picture of Taddeo's character, such as a story illustrating his cooperative spirit: when a Sienese painter friend, possibly Simone Martini or a follower, came to assist with some frescoes (perhaps on a ceiling or roof structure) and offered to take on a challenging section, Taddeo graciously accepted, demonstrating humility and collegiality.

Vasari also emphasized Taddeo's diligence and the quality of his work, noting that he surpassed all of Giotto's other disciples in judgment and talent, except perhaps Stefano Fiorentino and Maso di Banco, whom Vasari also admired. He praised Taddeo for his rich coloring and for his architectural achievements, particularly the Ponte Vecchio. While Vasari's accounts must be read with a critical eye, as they were written two centuries after Taddeo's life and sometimes contain inaccuracies or legendary elements, they provide a valuable glimpse into how Taddeo Gaddi was perceived by later generations and his established place in the Florentine artistic canon. His reputation for moral character, combined with his artistic talents, contributed to his esteemed position among his contemporaries and successors.

Challenges, Later Years, and Artistic Context

The mid-14th century was a period of significant upheaval in Florence and across Europe, most notably marked by the Black Death, the devastating plague pandemic that struck in 1348. This cataclysmic event had a profound impact on society, economy, and culture, including artistic production and patronage. While specific details of how the plague directly affected Taddeo Gaddi's career are not extensively documented, it undoubtedly shaped the environment in which he worked. The period following the Black Death saw shifts in religious sentiment and artistic themes, with an increased emphasis on penitence, mortality, and intercessory saints.

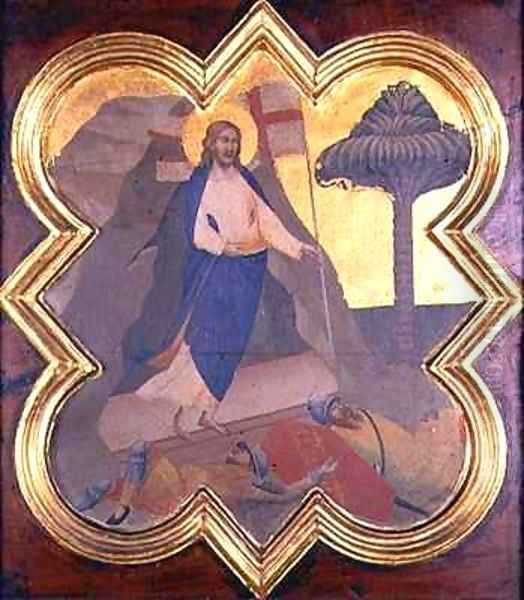

It is also recorded that Taddeo experienced periods of discouragement, particularly after the death of his master Giotto. The weight of carrying on such a significant legacy, coupled with potential health issues, may have presented personal challenges. Some art historians have noted that certain later works, or specific aspects of his oeuvre, such as some interpretations of the "Resurrection," might appear less innovative or more formulaic compared to his earlier achievements or the dynamic breakthroughs of Giotto. However, this is a nuanced assessment, as Taddeo continued to be a highly sought-after and respected artist throughout his career, adapting to the changing demands and tastes of his patrons. His sustained productivity until his death in 1366, and the continued success of his workshop under his son Agnolo, attest to his enduring relevance and skill in a challenging era. His contemporaries, such as Andrea Orcagna, also responded to the post-plague environment with powerful and sometimes somber works.

Conservation, Legacy, and Enduring Significance

Many of Taddeo Gaddi's works, particularly his large-scale frescoes, have faced the ravages of time, environmental factors, and sometimes ill-conceived earlier restorations. The aforementioned frescoes in the refectory of Santa Croce, including the "Last Supper" and "Tree of Life," were severely damaged by the 1966 Arno flood, which submerged large parts of Florence and caused catastrophic harm to countless artworks. The painstaking restoration of these works in the decades that followed is a testament to modern conservation science and the commitment to preserving Italy's artistic heritage. Other works by Taddeo, both frescoes and panel paintings, have undergone various conservation treatments over the centuries to stabilize them and, where possible, reveal their original appearance.

Taddeo Gaddi's legacy is multifaceted. As Giotto's most prominent and long-standing pupil, he played a crucial role in consolidating and disseminating the revolutionary artistic language of his master. He trained his own son, Agnolo, ensuring the continuation of a significant artistic workshop into the next generation. His innovations in the use of color, light, and complex narrative compositions, while building on Giotto's foundations, also pointed towards future developments in Florentine painting. Artists like Fra Angelico, active in the early 15th century, would later explore light and color with even greater sophistication, but Taddeo's experiments were important precursors. His works are found in major collections, including the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, the Alte Pinakothek in Munich, and the Staatliche Museen in Berlin, allowing his art to be studied and appreciated by a global audience. He remains a key figure for understanding the transition from the world of Giotto to the later developments of the Florentine Renaissance, a bridge between the foundational innovations of the early Trecento and the artistic currents that followed. His influence, combined with that of other Giotteschi like Maso di Banco and the Cione brothers (Andrea, Nardo, and Jacopo), shaped the artistic landscape of Florence for much of the 14th century.

Conclusion: A Luminous Disciple

Taddeo Gaddi was far more than a mere follower of Giotto; he was a gifted and intelligent artist who absorbed the lessons of his master and forged a distinctive path. His contributions to Florentine painting and architecture during a vibrant and transformative period were substantial. From the intimate narratives of the Baroncelli Chapel to the grand allegories of the Santa Croce refectory, and his reputed design for the Ponte Vecchio, Taddeo's work demonstrates a consistent quality, a refined sensibility, and a thoughtful engagement with the artistic challenges of his time. He successfully navigated the monumental legacy of Giotto, adding his own nuances of color, light, and narrative detail, thereby enriching the Giottesque tradition and ensuring its vitality for succeeding generations. His long and productive career, his influential workshop, and the enduring appeal of his art secure Taddeo Gaddi's place as one of the most important masters of the Italian Trecento.