Simone Martini stands as one of the most influential and refined painters of the Italian Trecento (14th century). A pivotal figure in the Sienese School, his work bridged the gap between the Byzantine traditions still prevalent in Italy and the burgeoning Gothic sensibilities arriving from Northern Europe. His art is celebrated for its lyrical lines, exquisite detail, vibrant color, and profound emotional resonance. Active primarily in Siena, Assisi, Naples, and finally Avignon, Martini's influence extended far beyond his native Tuscany, playing a crucial role in the development of the International Gothic style that would dominate European courtly art in the late medieval period.

Origins and Early Life in Siena

Simone Martini was born in the Republic of Siena, likely around the year 1284, although some historical sources suggest 1283. Siena, at this time, was a thriving city-state, a powerful rival to Florence in both political and artistic spheres. The Sienese school of painting had already established a distinct identity, characterized by a decorative richness, an emphasis on graceful linearity, and a conservative adherence to certain Byzantine conventions, albeit infused with a unique local sensitivity. This artistic environment, dominated by the legacy of painters like Coppo di Marcovaldo and Guido da Siena, and more immediately by the towering figure of Duccio di Buoninsegna, profoundly shaped Martini's early development.

Details about Simone's family background are scarce, but it is known he came from an artistic milieu. His later collaboration and family ties with Lippo Memmi, whose father Memmo di Filippuccio was also a painter active in Siena and San Gimignano, suggest a network of workshops and shared practices common in the era. Simone's emergence as a major artistic force occurred relatively early in his career, marked by significant public commissions that demonstrated his precocious talent and ambition.

The Question of Artistic Training

The precise nature of Simone Martini's artistic training remains a subject of scholarly debate. The most widely accepted view holds that he was a pupil of Duccio di Buoninsegna, the undisputed master of the previous generation of Sienese painters. Stylistic affinities, particularly in the elegance of line, the richness of decorative patterns, and certain compositional structures found in Simone's early works, lend credence to this theory. Duccio's monumental Maestà altarpiece for the Siena Cathedral, completed around 1311, would have been a formative influence on any young Sienese artist.

However, Simone's art quickly diverged from Duccio's more hieratic and Byzantine-influenced style. Martini incorporated a greater degree of naturalism, a more sophisticated understanding of spatial depth (though not linear perspective in the Renaissance sense), and a keen observation of human emotion, particularly evident in the subtle gestures and expressions of his figures. Some scholars have proposed that Simone may have had direct contact with the work of Giotto di Bondone, the Florentine innovator who revolutionized Italian painting. Giotto's emphasis on volume, dramatic narrative, and psychological realism certainly finds echoes, albeit transformed, in Martini's work, particularly in the frescoes at Assisi. Whether this influence came from direct apprenticeship, observation of Giotto's work (perhaps in Assisi itself), or through intermediary artists remains uncertain. Regardless of his specific master, Simone synthesized these diverse influences into a highly personal and original style.

The Siena Maestà: A Civic Statement

One of Simone Martini's earliest documented and most significant commissions was the Maestà fresco, painted for the Sala del Mappamondo (Hall of the Globe) in Siena's Palazzo Pubblico (Town Hall). Completed in 1315 and later retouched by Simone himself in 1321, this monumental work depicts the Virgin Mary enthroned as Queen of Heaven, holding the Christ Child and surrounded by a celestial court of angels and saints, including Siena's patron saints (Ansanus, Savinus, Crescentius, and Victor).

While clearly inspired by Duccio's Maestà for the cathedral, Simone's version differs significantly in medium (fresco versus tempera on panel), setting (civic palace versus cathedral), and style. Simone's Maestà possesses a more courtly elegance and a greater sense of three-dimensional space, achieved through the elaborate canopy structure and the overlapping arrangement of figures. The Virgin is portrayed with regal grace, yet her gaze and gentle inclination towards the Child introduce a note of human tenderness. The intricate details of the textiles, the delicate rendering of faces and hair, and the sophisticated use of color and gold leaf showcase Martini's technical mastery and his affinity for Gothic refinement. This fresco served not only as a devotional image but also as a powerful symbol of Sienese civic pride and divine protection.

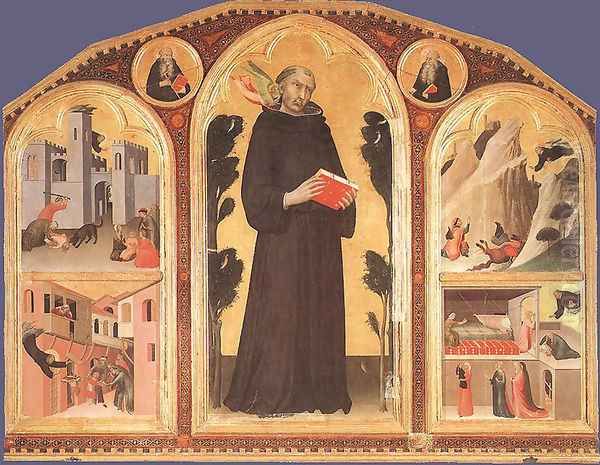

Assisi: The Chapel of St. Martin

Perhaps Simone Martini's most extensive and celebrated fresco cycle is found in the Chapel of St. Martin, located in the Lower Church of the Basilica of Saint Francis in Assisi. Commissioned likely by Cardinal Gentile Partino da Montefiore and probably executed between 1317 and 1319, these frescoes narrate the life of St. Martin of Tours, a 4th-century Roman soldier who became a bishop renowned for his charity.

The ten episodes depicted showcase Martini's mature style, blending narrative clarity with courtly elegance. Scenes like St. Martin Renouncing His Arms, The Investiture of St. Martin as a Knight, and The Dream of St. Martin are rendered with meticulous attention to contemporary costume, architecture, and detail, creating a vivid, almost chivalric atmosphere. Simone masterfully conveys emotion through gesture and expression, from the saint's piety to the interactions within the bustling courtly scenes. The use of color is particularly striking, with rich blues, reds, and golds creating a luminous effect. The Assisi frescoes demonstrate Simone's ability to adapt his Sienese grace to large-scale narrative painting, rivaling the dramatic power of Giotto, whose own influential frescoes adorned the Upper Church nearby. The presence of both masters' work in Assisi provides a fascinating comparison between the Florentine and Sienese approaches to fresco painting in the early 14th century.

Royal Patronage in Naples

Simone Martini's fame extended beyond Tuscany and Umbria. Around 1317, he was summoned to Naples to work for the Angevin king, Robert of Anjou. His major commission there was the large panel painting depicting St. Louis of Toulouse Crowning His Brother Robert of Anjou. St. Louis, an Angevin prince who renounced his claim to the throne to join the Franciscan order, had recently been canonized, and the painting served to legitimize Robert's rule by associating him with his saintly sibling.

This work, now housed in the Museo di Capodimonte in Naples, is remarkable for its political iconography and its artistic execution. Simone portrays the historical figures with portrait-like specificity, a significant step towards realism. St. Louis, clad in Franciscan robes over rich episcopal vestments, places the earthly crown on Robert's head while angels bestow a heavenly crown upon the saint himself. The intricate tooling of the gold background, the detailed rendering of the royal fleur-de-lis motif, and the overall regal splendor make this one of the key works of early Trecento panel painting, demonstrating Simone's ability to cater to the sophisticated tastes of royal patrons. Other works attributed to his Neapolitan period further attest to his activity in the Angevin court.

Collaboration with Lippo Memmi: The Annunciation

Simone Martini's artistic practice often involved collaboration, a common feature of medieval and Renaissance workshops. His most significant collaborator was Lippo Memmi, who was not only a fellow painter but also his brother-in-law (Simone married Lippo's sister Giovanna in 1324). While Lippo Memmi was a capable artist in his own right, often working in a style closely related to Simone's, their joint projects highlight a synergy that produced some of the era's masterpieces.

Their most famous collaboration is the Annunciation with Two Saints (St. Ansanus and St. Maxima, or possibly St. Margaret), painted in 1333 for the altar of St. Ansanus in Siena Cathedral and now a centerpiece of the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. This work is widely regarded as a high point of Gothic panel painting. The central panel, depicting the Archangel Gabriel announcing the divine conception to the Virgin Mary, is generally attributed primarily to Simone. Gabriel, holding an olive branch, has just alighted, his cloak still swirling. Mary, interrupted in her reading, shrinks back with a graceful S-curve posture, her expression a mixture of surprise, humility, and perhaps apprehension. The words of the angel, "Ave Maria Gratia Plena Dominus Tecum," are inscribed in raised gesso across the gold background. The flanking saints are often attributed to Lippo Memmi. The painting's elongated figures, flowing lines, exquisite detail (like the vase of lilies symbolizing Mary's purity), and shimmering gold background epitomize the elegance and decorative beauty of the International Gothic style, of which Simone was a key progenitor. Disentangling the precise contributions of each artist in their collaborations remains a challenge for art historians, but the Annunciation stands as a testament to their shared artistic vision.

The Guidoriccio da Fogliano Controversy

Another famous fresco in Siena's Palazzo Pubblico, long considered one of Simone Martini's signature works, is the equestrian portrait of Guidoriccio da Fogliano. Located opposite the Maestà in the Sala del Mappamondo, it commemorates the Sienese mercenary captain's capture of the castles of Montemassi and Sassoforte in 1328. The fresco depicts Guidoriccio, clad in magnificent diamond-patterned attire matching his horse's caparison, riding triumphantly across a barren landscape dotted with military camps and the captured fortresses. For centuries, this image was celebrated as a groundbreaking example of secular portraiture and landscape painting, attributed to Simone based on stylistic analysis and early sources, with a presumed execution date around 1330.

However, in the late 20th century, the attribution and dating of the Guidoriccio fresco became the subject of intense debate. The discovery of another, underlying fresco depicting a different scene, possibly by Duccio, complicated the chronology. Furthermore, some scholars questioned the style, arguing it seemed inconsistent with Simone's documented works from the period and might even be a later creation, perhaps by a different artist altogether, or even a much later reconstruction. Others vehemently defend the traditional attribution to Simone, citing documentary evidence and stylistic parallels. The controversy remains unresolved, making the Guidoriccio one of the most debated works in Italian art history, highlighting the complexities of attribution based solely on style and incomplete historical records. Despite the debate, the image itself remains iconic.

The Move to Avignon and Petrarch

In the latter part of his career, around 1336 or shortly thereafter, Simone Martini moved from Italy to Avignon in southern France. Avignon was, at this time, the seat of the Papacy (the "Avignon Papacy," 1309-1376), making it a major international center of politics, religion, and culture. The papal court attracted artists, intellectuals, and patrons from across Europe, creating a cosmopolitan environment where Italian and French artistic traditions could intermingle. Simone worked for the papal court, including commissions under Pope Benedict XII.

During his time in Avignon, Simone formed a notable friendship with the celebrated Italian poet and humanist, Francesco Petrarca (Petrarch). Petrarch held Simone's art in high esteem, mentioning him in two of his sonnets where he praises the artist's skill in capturing the likeness of his beloved Laura (presumably in a portrait, now lost). Simone is also credited with illuminating the frontispiece of a manuscript of Virgil owned by Petrarch (now in the Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Milan). This illumination depicts Virgil writing, attended by his commentator Servius and allegorical figures, showcasing Simone's delicate miniature style. His presence in Avignon was crucial for disseminating the Sienese style and contributing to the formation of the International Gothic style, influencing French artists like Matteo Giovanetti, who also worked at the papal palace. Simone Martini died in Avignon in the summer of 1344, specifically on June 30th according to reliable records, leaving a significant mark on both Italian and French art.

Simone Martini and the International Gothic Style

Simone Martini is considered one of the most important figures in the development and dissemination of the International Gothic style. This style, flourishing in the courts of Europe roughly between 1375 and 1425, evolved from the fusion of Italian (particularly Sienese) elegance and Northern European Gothic traditions. Its key characteristics include aristocratic refinement, intricate decorative patterns, slender and gracefully swaying figures (often with an S-curve posture), rich colors, extensive use of gold, and a focus on detailed observation of costumes, textiles, and natural elements, often within secular or courtly contexts alongside religious themes.

Martini's work embodies many of these traits. His emphasis on sinuous lines, delicate modeling, expressive gestures, luxurious detail, and vibrant, jewel-like colors appealed to the sophisticated tastes of patrons in Siena, Naples, and Avignon. His Annunciation is often cited as a quintessential example anticipating the International Gothic aesthetic. By working at the papal court in Avignon, a crossroads of European culture, Simone's style directly influenced artists from France, the Low Countries, and beyond. Artists associated with the later, full flowering of the style, such as the Limbourg Brothers (famous for the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry), Gentile da Fabriano (Adoration of the Magi), and Pisanello, owe a debt to the foundations laid by Simone Martini's elegant and courtly art.

Artistic Techniques and Refinement

Simone Martini was a master craftsman, proficient in both fresco and tempera panel painting. His technique was characterized by meticulous attention to detail and a pursuit of decorative richness. In his panel paintings, he employed traditional tempera techniques, mixing pigments with egg yolk to create luminous, durable colors. He was particularly skilled in the use of gold leaf, not just for backgrounds but also for intricate tooling (punchwork) to create patterns on halos, borders, and garments, enhancing the shimmering, otherworldly effect of his sacred images.

His drawing, underlying both frescoes and panels, was exceptionally refined. The hallmark of his style is the fluid, calligraphic line that defines contours and drapery folds with effortless grace. This linear quality connects his work to Sienese tradition but also to the elegance of French Gothic manuscript illumination and sculpture. While not achieving the volumetric solidity of Giotto, Simone created believable figures through subtle modeling and expressive postures. His color palette was sophisticated and varied, often employing expensive pigments like lapis lazuli for brilliant blues, contributing to the precious quality of his work. Some sources mention innovative techniques aimed at achieving particular luminosity or iridescence, reflecting his experimental approach within the established traditions.

Influence and Legacy in Sienese Art

Simone Martini's impact on the Sienese school was profound and lasting, rivaling that of Duccio. He introduced a new level of sophistication, naturalism, and emotional subtlety, blended with Gothic elegance, which influenced subsequent generations of Sienese painters. His brother-in-law, Lippo Memmi, was his closest follower and collaborator. Other artists whose work shows Simone's influence include Barna da Siena, Andrea Vanni, and the Master of the Palazzo Venezia Madonna.

While Simone represented the more courtly and Gothicizing trend within Sienese art, his contemporaries, the brothers Ambrogio Lorenzetti and Pietro Lorenzetti, pursued a different path, more closely aligned with Giotto's naturalism and interest in spatial construction and human drama (as seen in Ambrogio's Allegory of Good and Bad Government frescoes, also in the Palazzo Pubblico). Together, Simone Martini and the Lorenzetti brothers represent the high point of Sienese painting in the 14th century, establishing Siena as a major artistic center distinct from Florence. However, the devastating Black Death of 1348, which claimed Ambrogio and Pietro Lorenzetti (and occurred shortly after Simone's death), dealt a severe blow to Siena, and while the Sienese school continued, it arguably never fully regained the innovative momentum of the first half of the Trecento. Simone's legacy, however, endured, particularly through the widespread influence of the International Gothic style he helped to shape. Other Florentine contemporaries like Taddeo Gaddi, Bernardo Daddi, and Maso di Banco, while primarily followers of Giotto, operated within the same broader artistic context of the Italian Trecento.

Surviving Works and Their Locations

Simone Martini's surviving works are distributed among major museums and churches, primarily in Italy but also elsewhere in Europe and the United States. Key locations include:

Siena: The Palazzo Pubblico houses the Maestà and the Guidoriccio da Fogliano (despite attribution debates). The Pinacoteca Nazionale di Siena holds several panels.

Florence: The Uffizi Gallery holds the iconic Annunciation (with Lippo Memmi).

Assisi: The Lower Church of the Basilica of Saint Francis contains the vital fresco cycle in the Chapel of St. Martin.

Naples: The Museo di Capodimonte houses the St. Louis of Toulouse Crowning Robert of Anjou.

Pisa: The Museo Nazionale di San Matteo holds the Polyptych of Santa Caterina d'Alessandria.

Orvieto: The Museo dell'Opera del Duomo holds several works, including the Madonna and Child with Saints Polyptych.

Liverpool (UK): The Walker Art Gallery has the panel Christ Discovered in the Temple.

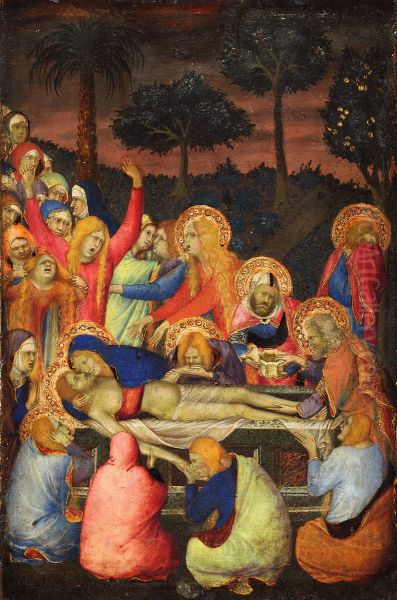

Antwerp (Belgium): The Royal Museum of Fine Arts holds panels from the Orsini Polyptych (The Carrying of the Cross, The Crucifixion, The Deposition).

Paris (France): The Louvre Museum holds The Carrying of the Cross, another panel from the Orsini Polyptych.

Berlin (Germany): The Gemäldegalerie holds The Entombment from the Orsini Polyptych.

St. Petersburg (Russia): The Hermitage Museum holds a Madonna from an Annunciation.

Washington D.C. (USA): The National Gallery of Art holds a Madonna and Child.

Boston (USA): The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum holds a Madonna and Child with Saints.

Recent exhibitions and ongoing research continue to shed light on Simone Martini's career, techniques, and influence, reaffirming his status as a pivotal master of the Italian Trecento. A conference in Pisa in 2017 focused on his political paintings, and works like the panel recently displayed at London's National Gallery in 2024 continue to captivate audiences.

Conclusion: A Master of Grace and Innovation

Simone Martini remains a towering figure in the history of art, a master whose work epitomizes the refined elegance of the Sienese school while simultaneously paving the way for the International Gothic style. His ability to synthesize the decorative traditions of Siena with the emerging naturalism and emotional depth found in the work of contemporaries like Giotto, all infused with the grace of French Gothic art, resulted in a unique and highly influential style. From the civic grandeur of the Siena Maestà to the narrative richness of the Assisi frescoes and the exquisite refinement of the Uffizi Annunciation, his works are characterized by lyrical lines, luminous color, intricate detail, and a subtle psychological penetration. Though controversies surround the attribution of some works, his core achievements remain undeniable. Simone Martini's art transcends its historical context, continuing to enchant viewers with its delicate beauty and sophisticated artistry, securing his place as one of the essential painters of the late medieval period.