Gentile da Fabriano, born Gentile di Niccolò di Giovanni di Massio around 1370 in or near Fabriano, in the Marche region of Italy, stands as one of the most pivotal and enchanting figures of early fifteenth-century Italian art. His lifespan, concluding in Rome in 1427, places him at a fascinating crossroads in art history: the flourishing peak of the International Gothic style and the burgeoning dawn of the Early Renaissance. Gentile masterfully navigated these currents, creating works of exquisite beauty, refined craftsmanship, and burgeoning naturalism that captivated his contemporaries and left an indelible mark on the generations of artists who followed. His art is a testament to a period of transition, embodying the courtly elegance and decorative richness of the Gothic tradition while simultaneously embracing new humanist interests in observation, emotion, and the depiction of the natural world.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

The precise details of Gentile da Fabriano's early life and artistic training remain somewhat shrouded in the mists of time, a common challenge for art historians studying figures from this period. Born into a family of some standing – his father, Niccolò di Giovanni Massi, was a cloth merchant and civic figure who later entered a monastery, and his mother passed away before he was ten – Gentile's path to becoming a painter is not meticulously documented in its initial stages. It is widely believed that he received his foundational training in his native Marche region, possibly under a local master like Allegretto Nuzi, who was a prominent painter in Fabriano in the latter half of the 14th century.

However, Gentile's artistic horizons soon expanded beyond his provincial origins. Evidence suggests he may have spent time in Lombardy, perhaps in Milan, a vibrant center of the International Gothic style under the patronage of the Visconti dukes. The sophisticated, courtly aesthetics prevalent there, characterized by flowing lines, rich colors, and an emphasis on elegant detail, would certainly have resonated with Gentile's developing sensibilities. By 1408, his name begins to appear in records in Venice, a cosmopolitan hub where artistic ideas from Byzantium, the North, and across Italy converged.

Travels and Flourishing Career Across Italy

Gentile da Fabriano was an itinerant artist, a common practice for successful painters of his era who were sought after by patrons in various city-states. His career saw him undertake significant commissions in several major Italian artistic centers, each contributing to his fame and stylistic development.

Venice: The Doge's Palace and Early Acclaim

Gentile's presence in Venice is documented from around 1408 to 1414. During this period, he undertook a prestigious commission to paint frescoes in the Sala del Maggior Consiglio (Hall of the Great Council) in the Doge's Palace. These frescoes, depicting a naval battle between the Venetians and Otto III, are unfortunately lost, having been destroyed by fire in 1577. However, contemporary accounts and their very commission attest to the high regard in which Gentile was already held. It was in Venice that he likely came into contact with, and significantly influenced, younger artists such as Antonio Pisanello, who may have worked as his assistant on the Doge's Palace project, and Jacopo Bellini, the father of the renowned Venetian painters Giovanni Bellini and Gentile Bellini (named in honor of da Fabriano). His Venetian works, like the Madonna and Child with Angels (Perugia, Galleria Nazionale dell'Umbria), showcase his lyrical line, delicate modeling, and rich, jewel-like colors, hallmarks of the International Gothic style.

Brescia and the Malatesta Patronage

Around 1414, Gentile moved to Brescia, in Lombardy, where he worked for Pandolfo III Malatesta, a powerful condottiero and lord of Brescia and Bergamo. For Pandolfo, Gentile frescoed a chapel, likely in the Broletto (the old communal palace). These frescoes, too, are now lost, but their commission further underscores his growing reputation among the Italian nobility. The Malatesta family were significant patrons of the arts, and working for such a discerning client would have allowed Gentile to further refine his courtly style, emphasizing luxurious textiles, intricate patterns, and a sense of aristocratic splendor.

Florence: The Zenith with the Adoration of the Magi

Gentile's arrival in Florence around 1420 marked a pivotal moment in his career and in the history of Florentine art. Florence was then a crucible of artistic innovation, with artists like Filippo Brunelleschi, Donatello, and Masaccio pioneering a new Renaissance style grounded in classical principles, perspective, and a profound naturalism. Gentile, though steeped in the Gothic tradition, was not immune to these developments. In 1422, he enrolled in the Arte dei Medici e Speziali, the Florentine painters' guild.

His most famous surviving masterpiece, the Adoration of the Magi, was commissioned in 1423 by the wealthy Florentine banker Palla Strozzi for his family chapel in the church of Santa Trinita. Now housed in the Uffizi Gallery, this altarpiece is a dazzling summation of the International Gothic style at its most opulent and refined. The painting teems with life, featuring a magnificent procession of kings, courtiers, exotic animals, and meticulously rendered details of costume, armor, and landscape. Gentile's use of gold leaf is lavish, creating a shimmering, otherworldly effect, while his observation of nature – in the depiction of animals, plants, and even the subtle play of light – hints at the burgeoning Renaissance interest in the empirical world. The predella panels, including a remarkable night scene of the Nativity and the Flight into Egypt, further demonstrate his innovative approach to light and atmosphere. This work had a profound impact on Florentine artists, including Fra Angelico and Benozzo Gozzoli, who absorbed its narrative richness and decorative splendor.

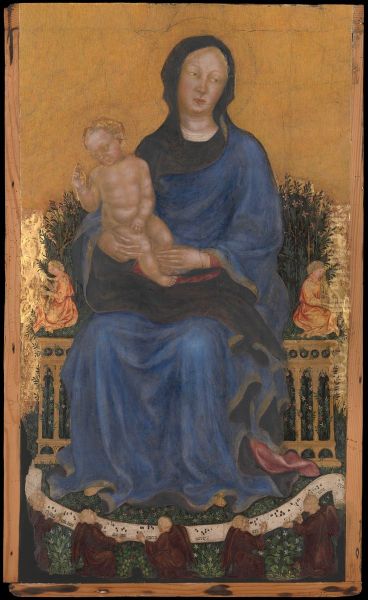

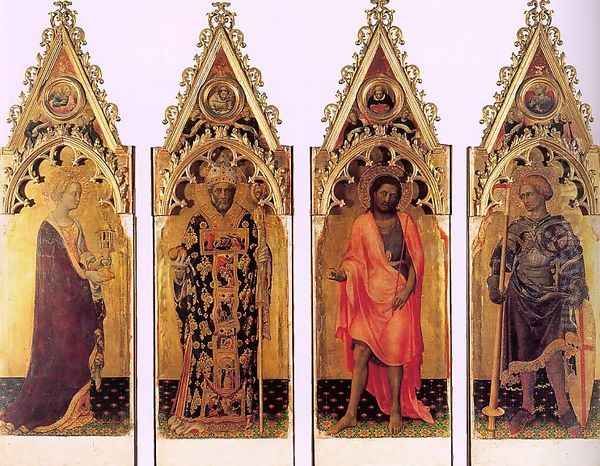

While in Florence, Gentile also completed the Quaratesi Polyptych in 1425 for the Quaratesi family chapel in the church of San Niccolò Oltrarno. Though now dismembered and its panels scattered across various museums (including the Uffizi, the Vatican, the National Gallery in London, and the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C.), the surviving elements reveal a more monumental and spatially aware approach, perhaps reflecting the influence of Florentine contemporaries like Masaccio. The central panel, Madonna and Child with Angels, shows a tender humanity and a sophisticated understanding of form.

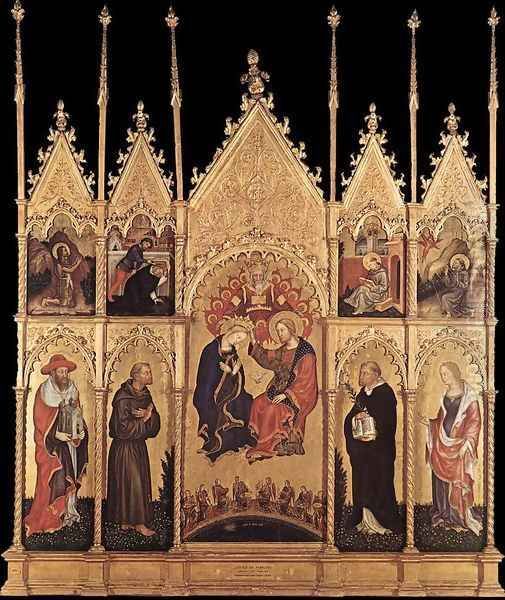

Siena, Orvieto, and the Papal Call to Rome

After his Florentine triumphs, Gentile's journey continued. He is documented in Siena in 1425, where he painted a Madonna and Child for the Palazzo dei Notai (now lost). The Sienese school, with artists like Sassetta and Giovanni di Paolo, had its own strong Gothic tradition, and Gentile's presence would have been noted. Later that year, he was in Orvieto, where he began a fresco of the Madonna and Child Enthroned in the Duomo (Cathedral). This work, though left unfinished by Gentile and later completed by other hands, still bears the imprint of his graceful style.

His reputation had by now reached the highest echelons of patronage. In 1426 or early 1427, Pope Martin V summoned Gentile to Rome to undertake a major fresco cycle in the Basilica of San Giovanni in Laterano (St. John Lateran), the Pope's cathedral. This was a commission of immense prestige, aimed at restoring the ancient basilica and asserting papal authority after the Western Schism. Gentile began work on scenes from the life of St. John the Baptist. Unfortunately, his death in August or September 1427 left this project incomplete. Antonio Pisanello, his former collaborator, was called upon to finish the cycle, though these frescoes too were later destroyed during renovations in the 17th century.

Artistic Style and Defining Characteristics

Gentile da Fabriano's art is a harmonious blend of late Gothic elegance and an emerging Renaissance sensibility. His style is characterized by several key features:

The Quintessence of International Gothic

Gentile is arguably the foremost Italian exponent of the International Gothic style. This style, prevalent in European courts around 1400, is marked by its aristocratic refinement, sinuous lines, vibrant and often symbolic use of color, and a profusion of decorative detail. Gentile's figures are typically elongated and graceful, clad in sumptuous, intricately patterned fabrics. He delighted in depicting the pageantry of courtly life, with its processions, rich attire, and exotic elements. The extensive use of gold leaf, not just for halos and backgrounds but also integrated into textiles and highlights, creates a sense of preciousness and divine radiance.

Burgeoning Naturalism and Narrative Richness

Despite the stylized elegance of his work, Gentile possessed a keen observational eye. His paintings are filled with remarkably naturalistic details: the textures of fur and velvet, the delicate rendering of flowers and plants, the individual characterization of animals (seen vividly in the Adoration of the Magi with its horses, monkeys, leopards, and falcons), and the subtle depiction of human emotion. He was a master storyteller, imbuing his religious scenes with a wealth of anecdotal detail that engages the viewer and brings the sacred narratives to life. His predella panels, often featuring landscapes and innovative light effects, show a particular interest in creating believable settings for his figures.

Mastery of Color, Light, and Gold

Gentile's palette is rich and luminous, employing expensive pigments like lapis lazuli for brilliant blues and vermilion for deep reds, often juxtaposed with the shimmering expanse of gold. He was skilled in using cangiante, a technique of modeling forms with contrasting colors to suggest volume and the play of light on fabric. His handling of light could be remarkably sophisticated for his time, as seen in the Nativity predella panel of the Strozzi Altarpiece, one of the earliest convincing night scenes in Italian art, where the divine light emanating from the Christ Child illuminates the surrounding figures and landscape. The way he tooled and punched the gold leaf to create varied textures and catch the light further enhanced the opulence and spiritual aura of his works.

Technical Prowess and Innovation

Gentile was a consummate craftsman. He employed techniques such as pastiglia (raised gesso) to give three-dimensional relief to elements like halos, crowns, and armor, enhancing their tactile reality and visual splendor. His meticulous attention to detail extended to every aspect of the painting, from the delicate rendering of hair and fur to the intricate patterns on brocades and the careful depiction of architectural settings. While not a pioneer of linear perspective in the manner of Brunelleschi or Masaccio, Gentile demonstrated an intuitive understanding of space, creating convincing, if not mathematically precise, settings for his figures.

Key Masterpieces: A Closer Look

While many of Gentile's works, particularly his large-scale fresco cycles, have been lost, those that survive offer a compelling insight into his genius.

The Adoration of the Magi (1423)

This altarpiece, Gentile's most celebrated work, is a veritable feast for the eyes. Commissioned by Palla Strozzi for his family chapel in Santa Trinita, Florence, it depicts the journey and arrival of the three Magi to worship the infant Christ. The main panel is a continuous narrative, with the Magi's procession winding through a fantastical landscape on the left, culminating in the act of adoration before the Virgin and Child on the right. The painting is a tour-de-force of International Gothic opulence: the Magi's robes are rendered in exquisite detail with gold brocades and fur linings; their retinue includes a diverse array of figures, horses, and exotic animals like monkeys and a leopard. Gentile's skill in capturing varied textures and his delight in anecdotal detail are everywhere apparent. The frame itself is an integral part of the work, with gilded Gothic arches and pinnacles, and three predella panels below: The Nativity, The Flight into Egypt, and The Presentation in the Temple (a copy, the original is in the Louvre). The Nativity is particularly noted for its innovative depiction of nocturnal light.

The Quaratesi Polyptych (1425)

Created for the Quaratesi family chapel in San Niccolò Oltrarno, Florence, this polyptych, though now dismembered, represents a slightly later phase in Gentile's Florentine period. The central panel, Madonna and Child with Angels (Royal Collection, UK, on loan to the National Gallery, London), shows a greater monumentality and a more tender, human interaction between the Virgin and Child compared to some of his earlier Madonnas. The figures have a greater sense of volume and presence. The side panels depicted Saints Mary Magdalene, Nicholas of Bari, John the Baptist, and George (all Uffizi, Florence). The predella panels (Vatican Pinacoteca and National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.) continued Gentile's tradition of lively narrative scenes. This work suggests Gentile was responding to the artistic innovations he encountered in Florence, perhaps tempering his Gothic exuberance with a greater classical sobriety.

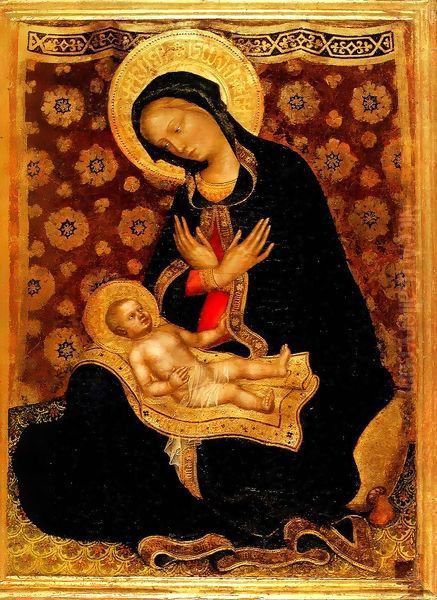

Madonna and Child (Yale University Art Gallery, c. 1420-1423)

This panel, often referred to as the Madonna of Humility or the Washington Madonna (another version is in the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.), exemplifies Gentile's skill in depicting the tender theme of the Virgin and Child. The Virgin is seated on a cushion on the ground, a pose symbolizing humility, yet she is adorned with a star-spangled blue mantle over a gold-embroidered gown. The Christ Child playfully interacts with his mother. The delicate modeling of the faces, the graceful flow of the drapery, and the rich decorative patterns are characteristic of Gentile's mature style.

The Presentation of Christ in the Temple (Louvre, Paris, c. 1423)

Originally a predella panel for the Strozzi Altarpiece, this work showcases Gentile's ability to handle complex multi-figure compositions within a small space. The scene is set within an elaborate architectural interior, and the figures, though small, are imbued with individual character and emotion. The soft colors and meticulous detail are typical of his refined craftsmanship.

Anecdotes, Controversies, and Historical Context

Gentile's life, while not as tumultuous as some of his contemporaries, was not without its interesting facets. His early orphan status and his father's retreat to a monastery paint a picture of a youth who had to forge his own path. The very fact that he was so sought after across Italy speaks volumes about his contemporary fame.

One notable "controversy," or rather a point of contemporary critique, is mentioned regarding his frescoes in St. John Lateran. Some sources suggest that certain elements, perhaps the inclusion of exotic animals like lions and camels or the sheer richness of the decoration, were deemed by some observers as "unnecessary and harmful" to the sacred dignity of the location. This highlights the ongoing tension in religious art between decorative splendor, intended to glorify God, and a more austere approach focused solely on spiritual didacticism.

There were also practical challenges. The preservation of his works has been a concern. The Quaratesi Polyptych, for instance, suffered from being dismantled and its panels dispersed, and some parts have endured damage over time. This fragmentation is a common fate for many polyptychs from this era.

Academic debates also surround Gentile. The precise extent of collaboration with artists like Pisanello is a subject of ongoing scholarly discussion. Attributions of some early works remain debated, and the exact chronology of his movements and commissions is pieced together from often sparse documentary evidence. For instance, the exact nature of his early training and the influence of Lombard art are still areas of active research.

His time in Florence placed him in direct dialogue with the nascent Renaissance. While Masaccio was revolutionizing painting with his stark realism, monumental figures, and mastery of perspective in works like the Brancacci Chapel frescoes (executed with Masolino, who himself retained more Gothicizing tendencies), Gentile offered a different, though equally compelling, vision. His art, with its emphasis on beauty, grace, and intricate detail, appealed to a wealthy clientele that appreciated courtly elegance and refined craftsmanship. Artists like Lorenzo Monaco were also working in Florence in a sophisticated late Gothic style, providing a rich artistic environment.

Influence and Lasting Legacy

Gentile da Fabriano's influence on subsequent generations of artists was profound and multifaceted.

Immediate Followers and Students

His most direct impact was on artists who worked with him or were active in the same centers. Jacopo Bellini, who likely knew Gentile in Venice and Florence, adopted his master's rich color, interest in detail, and narrative approach. Jacopo, in turn, passed these qualities on to his sons, Giovanni Bellini and Gentile Bellini, who became leading figures of the Venetian Renaissance. Giovanni, in particular, combined Gentile's coloristic richness with a new monumentality and emotional depth.

Antonio Pisanello, often considered Gentile's closest artistic heir, continued the International Gothic tradition with his exquisite drawings of animals and courtly figures, and his renowned portrait medals. Pisanello's work shares Gentile's meticulous attention to detail and love for the natural world.

Domenico Veneziano, another significant painter of the Early Renaissance, is thought to have had contact with Gentile's circle, and his own luminous palette and interest in light may owe something to Gentile's example. Domenico Veneziano, in turn, was a teacher of Piero della Francesca, one of the giants of the Quattrocento.

Impact on Florentine and Central Italian Art

In Florence, Gentile's Adoration of the Magi was a landmark. Fra Angelico, a Dominican friar and painter, was deeply influenced by Gentile's radiant color, use of gold, and serene spirituality. Fra Angelico's own altarpieces and frescoes, while imbued with a profound religious devotion, share Gentile's delight in beauty and intricate detail. Benozzo Gozzoli, a student of Fra Angelico, explicitly emulated the processional splendor of Gentile's Adoration in his famous frescoes of the Journey of the Magi in the Palazzo Medici-Riccardi in Florence.

Even artists who pursued a more radically Renaissance path, like Masaccio, would have been aware of Gentile's work. While Masaccio's style was a departure, Gentile's presence in Florence enriched the artistic landscape and provided a high standard of craftsmanship and painterly refinement.

Further south, his influence can be traced in the works of Sienese painters and artists in the Marche. His ability to blend decorative richness with observed reality provided a model for many.

A Bridge Between Styles

Gentile da Fabriano is often described as a transitional figure, bridging the gap between the International Gothic and the Early Renaissance. He was not a revolutionary in the mold of Brunelleschi or Masaccio, who fundamentally altered the course of Western art with their development of linear perspective and a new, human-centered naturalism. Instead, Gentile perfected the existing Gothic tradition, infusing it with a fresh sensitivity to the natural world and a gentle humanity. His art represents a "different Renaissance," one that valued elegance, ornament, and narrative charm alongside the emerging interest in scientific naturalism.

Later Reappraisal

While his fame was immense during his lifetime, Gentile's style was gradually superseded by the more robust and classically inspired forms of the High Renaissance. However, art historians have long recognized his crucial role. Giorgio Vasari, in his Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (1550, revised 1568), praised Gentile's skill and the beauty of his work, noting his gentle personality reflected in his name ("Gentile" meaning "gentle" or "courteous"). Modern scholarship continues to appreciate the unique synthesis he achieved, recognizing him as a master whose work embodies the sophisticated and cosmopolitan artistic culture of the early 15th century. Artists like Titian and Giorgione, who trained in Giovanni Bellini's workshop, inherited a Venetian tradition of color and light that ultimately had roots in Gentile's legacy.

Conclusion: An Enduring Radiance

Gentile da Fabriano remains a captivating figure in the history of art. His paintings, with their luminous colors, exquisite details, and gentle charm, transport viewers to a world of courtly splendor and profound religious sentiment. He was a master of his craft, capable of creating works of breathtaking beauty that delighted patrons across Italy, from Venice and Brescia to Florence, Siena, Orvieto, and Rome. While firmly rooted in the International Gothic style, his keen observation of nature, his ability to convey human emotion, and his sophisticated use of light and color mark him as an artist who also looked towards the future. His influence on contemporaries like Pisanello and Jacopo Bellini, and on subsequent masters such as Fra Angelico, Benozzo Gozzoli, and the Bellini dynasty, underscores his importance. Gentile da Fabriano's art is a radiant testament to a pivotal moment in European culture, a luminous bridge between the medieval world and the dawning Renaissance, and his legacy continues to enchant and inspire.