Laverne Nelson Black stands as a significant, if sometimes underappreciated, figure in the canon of early twentieth-century American Western art. His canvases, vibrant with the spirit of the Southwest, offer a compelling window into the lives of Native American peoples and the majestic landscapes they inhabited. Working during a transformative period in American art, Black skillfully blended traditional representational techniques with the burgeoning influences of Impressionism and Modernism, creating a body of work that is both historically evocative and aesthetically engaging. His life, though relatively short, was one of dedicated artistic pursuit, leaving behind a legacy that continues to captivate collectors and art historians alike.

Early Life and Artistic Seeds in Wisconsin

Born in 1887 in the small town of Viola, Wisconsin, Laverne Nelson Black's formative years were uniquely positioned to instill in him a deep fascination with Native American culture. His childhood home was situated near the Kickapoo River valley, an area with a rich indigenous heritage and in proximity to a Kickapoo settlement. This early exposure to a different way of life, to the customs, attire, and stories of the local Native American communities, undoubtedly planted the seeds for his lifelong artistic preoccupation. It was an environment that offered a stark contrast to the rapidly industrializing American Midwest, providing a glimpse into a world deeply connected to nature and tradition.

Even from a young age, Black exhibited a natural inclination towards art. The vibrant visual tapestry of Native American life, coupled with the scenic beauty of rural Wisconsin, likely provided ample inspiration for his earliest artistic endeavors. While details of his very early, informal artistic training are scarce, it is clear that his passion was strong enough to lead him towards a more formal path of study, a path that would eventually take him away from the familiar landscapes of his youth to the bustling artistic hub of Chicago.

Formal Training and the Chicago Years

To hone his innate talent, Laverne Nelson Black made his way to the prestigious Art Institute of Chicago. This institution was, and remains, one of America's foremost art schools, offering rigorous training in classical techniques while also exposing students to contemporary artistic currents. At the Art Institute, Black would have received comprehensive instruction in drawing, painting, and composition. He would have studied the works of Old Masters and been introduced to the Impressionist movement, which, though established in Europe, was still making significant inroads in American art circles.

Following his formal education, Black embarked on a career as a commercial illustrator in Chicago. This period was crucial for his development. Commercial illustration demanded discipline, an ability to meet deadlines, and a keen understanding of narrative and visual communication. It also required versatility, as illustrators often worked on a wide range of subjects. While perhaps not as creatively liberating as fine art painting, this work provided Black with a steady income and, importantly, kept his artistic skills sharp. The experience gained in conveying stories and moods through images would serve him well in his later easel painting, particularly in his depictions of Native American life and Western scenes, which often carry a strong narrative or atmospheric quality. The bustling urban environment of Chicago, however, would eventually give way to a different calling.

The Lure of the Southwest: Taos and Santa Fe

The year 1925 marked a pivotal turning point in Laverne Nelson Black's life and career. Drawn by the burgeoning reputation of New Mexico as an artist's haven, and undoubtedly by his enduring interest in Native American cultures, he relocated to the Southwest. He initially spent time in Taos before settling more permanently in Santa Fe. This region, with its unique light, dramatic landscapes, and vibrant indigenous cultures—particularly the Pueblo peoples—was a magnet for artists from across the country and Europe.

The artistic communities in Taos and Santa Fe were thriving. The Taos Society of Artists, founded in 1915 by figures such as Bert Geer Phillips, Ernest L. Blumenschein, Joseph Henry Sharp, Oscar E. Berninghaus, E. Irving Couse, and W. Herbert "Buck" Dunton, had already established Taos as a significant center for art focused on Southwestern themes. While Black was not a formal member of the original Taos Society of Artists (which had largely disbanded by the time he became prominent in the area), he was undoubtedly part of the broader "Taos art colony" ethos and was deeply influenced by the work and artistic philosophies of these pioneers. Artists like Walter Ufer and Victor Higgins, who joined the Society later, also contributed to the rich artistic dialogue of the region.

In this stimulating environment, Black's art truly blossomed. The intense, clear light of New Mexico, so different from the diffused light of the Midwest, encouraged a brighter palette and a more Impressionistic approach to capturing fleeting effects of light and color. The readily available subject matter—the daily lives of the Pueblo people, their ceremonies, their ancient architecture, and the breathtaking landscapes—provided endless inspiration.

Artistic Style: A Fusion of Impressionism and Realism

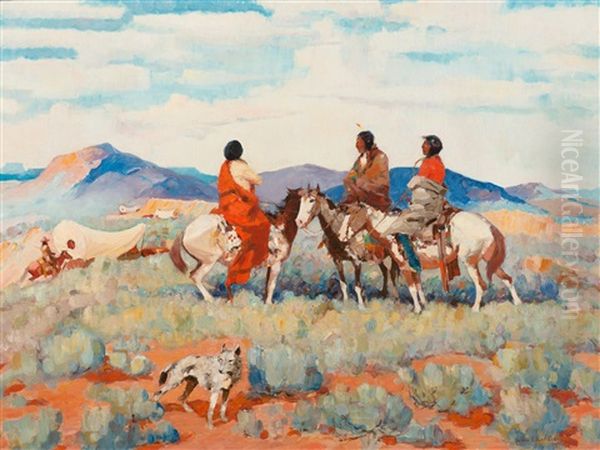

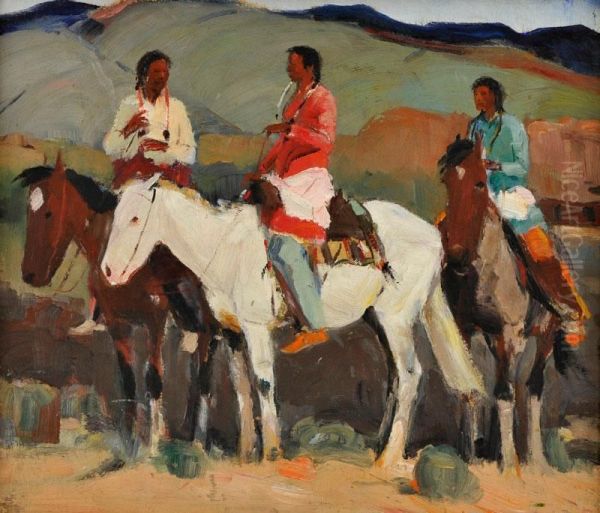

Laverne Nelson Black's mature artistic style is characterized by a dynamic fusion of Impressionistic technique and a deep-seated Realism, all applied to distinctly Western American subjects. He was particularly adept at capturing the energy and movement of his subjects, whether it was a Native American rider on horseback, a ceremonial dance, or the play of light across an adobe wall.

His brushwork is often described as broad, energetic, and confident, hallmarks of an Impressionistic approach. He wasn't afraid to let the brushstrokes remain visible, contributing to the vibrancy and immediacy of his canvases. This technique allowed him to convey a sense of fleeting moments and the shimmering quality of Southwestern light. His use of color was also influenced by Impressionism, often employing a brighter, more luminous palette than many of his more strictly academic contemporaries. He skillfully used color to define form, create atmosphere, and evoke emotion.

However, Black's work never fully dissolved into pure Impressionistic abstraction. A strong foundation in academic Realism, likely reinforced during his time at the Art Institute of Chicago and as an illustrator, remained evident. His figures are solidly rendered, his understanding of anatomy, particularly that of horses, is clear, and his compositions are thoughtfully constructed. He paid close attention to the details of Native American attire, customs, and the specific characteristics of the Southwestern landscape, lending an air of authenticity to his depictions. It was this ability to combine the atmospheric qualities of Impressionism with the narrative clarity of Realism that set his work apart. He learned from artists like Oscar E. Berninghaus and William Dunton, who emphasized the use of vivid color and strong compositional elements to enhance the storytelling power of their paintings.

Themes and Subjects: Chronicling a Disappearing West

The primary focus of Laverne Nelson Black's oeuvre was the American West, with a particular emphasis on Native American life and culture. He approached these subjects with a sensitivity and respect that was not always common among artists of his era. His paintings often depict Native Americans engaged in daily activities, on horseback traversing the vast landscapes, or participating in traditional ceremonies. These are not romanticized, stereotypical portrayals, but rather observations that seem grounded in a genuine interest and appreciation for his subjects.

Horses feature prominently in Black's work, and he depicted them with remarkable skill and dynamism. Whether carrying a solitary rider against a dramatic sky or as part of a larger group, his horses are full of life and energy. They are integral to his vision of the West, symbolizing freedom, movement, and the close relationship between humans and animals in that environment.

The landscapes themselves are also a key subject. Black captured the unique geological formations, the vast open skies, and the distinctive flora of New Mexico and the broader Southwest. His landscapes are rarely empty; they often serve as a backdrop for human or animal activity, emphasizing the interconnectedness of life in this often-harsh but beautiful environment. Through his work, Black sought to document and celebrate a way of life and a landscape that were rapidly changing in the face of modernization. His paintings serve as a visual record of this transitional period, imbued with a sense of both admiration and, perhaps, a touch of melancholy for the passing of an era. Other artists of the period, such as Maynard Dixon, also focused on the changing West, often with a more modernist and starkly monumental approach, while figures like Frederic Remington and Charles M. Russell, though largely preceding Black's peak, had set a precedent for depicting the action and narrative of Western life. Black's work can be seen as continuing this tradition but filtering it through a more modern, impressionistic lens.

Notable Works and Public Commissions

Several works by Laverne Nelson Black stand out as representative of his style and thematic concerns. "Along the Old Trail," completed in 1927, is one of his most recognized paintings. This piece, depicting Native American riders moving through a sun-dappled, autumnal landscape, showcases his masterful use of light, color, and dynamic composition. Its enduring appeal is evidenced by its selection as the BNSF (Burlington Northern Santa Fe) Railway's safety logo in 2008, introducing his work to a new generation.

Another notable piece is "Taos Scout," which exemplifies his skill in portraying solitary figures within the expansive Western landscape, capturing a sense of quiet dignity and connection to the environment. "Indian on Horseback" is another title that frequently appears in discussions of his work, indicative of his recurring and favored themes.

Beyond his easel paintings, Black also undertook significant public commissions. He created murals for the Santa Fe Railway, a major patron of Southwestern art, which sought to promote tourism and the allure of the West through compelling imagery. Additionally, during the Great Depression, Black participated in the Works Progress Administration (WPA) Federal Art Project. The WPA commissioned artists to create public art, providing them with much-needed employment and enriching communities with murals and sculptures. Black's involvement in these projects demonstrates his standing within the artistic community and his contribution to the broader cultural landscape of the time. These public works, often displayed in post offices, libraries, and other government buildings, brought art to a wider audience and helped to foster a sense of national identity and regional pride.

Contemporaries and the Artistic Milieu

Laverne Nelson Black worked during a vibrant period for American art, particularly for art of the American West. As mentioned, the Taos Society of Artists, including founders like Phillips, Blumenschein, Sharp, Berninghaus, Couse, and Dunton, along with later members like Ufer, Higgins, E. Martin Hennings, and Catharine Critcher, created a powerful artistic center. These artists, while sharing a common interest in Southwestern themes, each developed individual styles, contributing to a rich and diverse artistic output from the region.

Beyond the immediate Taos circle, other artists were also exploring Western subjects. Maynard Dixon, with his distinctive modernist style, depicted the landscapes and peoples of the West with a stark, monumental quality. Frank Tenney Johnson was known for his nocturnes and atmospheric portrayals of cowboys and Western life, often employing a more tonalist approach. While the legendary figures of Frederic Remington and Charles M. Russell belonged to a slightly earlier generation, their influence on the perception and depiction of the West was pervasive and undoubtedly informed the artists who followed, including Black.

In the broader American art scene, movements like the Ashcan School, with artists such as Robert Henri (who also spent time in Santa Fe and influenced artists there), were focusing on contemporary urban life, while American Impressionists like Childe Hassam were adapting French Impressionism to American landscapes and cityscapes. Black's work, therefore, can be seen as part of a larger artistic conversation, where artists were grappling with American identity, regional distinctiveness, and the evolving language of modern art. His choice to focus on the West, and his particular stylistic fusion, carved out a unique niche for him within this dynamic environment.

Recognition, Exhibitions, and Market Presence

Throughout his career, Laverne Nelson Black's work gained increasing recognition, though perhaps not the widespread fame of some of his Taos contemporaries during his lifetime. His Impressionistic style, while accepted in some circles, was not universally popular in the earlier part of his career, especially in more conservative Western art markets. However, by the 1930s, his talent and unique vision were more broadly acknowledged. He exhibited his work in various regional and national shows, contributing to his growing reputation.

In the decades since his death, Black's paintings have become sought after by collectors of Western American art. His works regularly appear at auction, handled by reputable auction houses such as John Moran Auctioneers, which has featured his paintings in sales dedicated to Californian and American art. His inclusion in significant private collections, such as the L.D. "Brink" Brinkman Collection (which featured his "Indian on Horseback"), further attests to his importance.

The market for his work reflects this appreciation. While auction prices can vary significantly based on the size, subject matter, condition, and provenance of a piece, his paintings can command substantial sums. For instance, "Taos Scout" was noted to have sold in a range of $6,000 to $8,000 at one point, while other, perhaps more significant or larger works, have achieved higher valuations. Reports from publications like Antiques and the Arts Weekly have mentioned estimates for exceptional Western art pieces, sometimes reaching into the hundreds of thousands of dollars (e.g., a general market mention of $250,000 to $350,000 for high-caliber works), indicating the strong collector interest in the genre to which Black contributed. His association with the Taos art scene and the inherent quality of his work ensure his continued presence and relevance in the art market.

Later Life and Enduring Legacy

Laverne Nelson Black's productive artistic career was cut short by his relatively early death in 1938, at the age of 51. He passed away in Chicago, the city where he had received his formal artistic training and begun his professional life, though his artistic heart had long belonged to the landscapes and peoples of the American Southwest.

Despite his shorter lifespan compared to some of his contemporaries, Black left behind a significant and compelling body of work. He is remembered as one of the important early 20th-century painters of the American West, an artist who successfully melded Impressionistic sensibilities with a deep respect for his subjects. His paintings offer a vibrant, empathetic, and historically valuable glimpse into Native American life and the majestic scenery of the Southwest during a period of profound change.

His legacy endures in the collections of museums, galleries, and private individuals who appreciate his unique artistic vision. His ability to capture the dynamic energy of the West, the play of light and color, and the dignity of its inhabitants ensures his place in the continuing story of American art. Laverne Nelson Black's canvases remain a testament to his skill, his passion, and the enduring allure of the American West. His work invites viewers to step into a world he knew and loved, a world he preserved with every thoughtful and energetic stroke of his brush.