Elling William "Bill" Gollings stands as a significant figure in the canon of American Western art. Active during a pivotal period when the open range era was drawing to a close, Gollings dedicated his artistic life to capturing the landscapes, people, and spirit of Wyoming and the broader American West. Born March 17, 1878, and passing away on April 16, 1932, his lifespan bridged the transition from the raw frontier to a more settled, yet still rugged, West. Known affectionately as the "Cowboy Artist," Gollings brought an authenticity to his work born from direct experience, setting him apart as a vital chronicler of a vanishing way of life. His contributions, rendered in oil, watercolor, and etching, offer invaluable visual records and artistic interpretations of the daily realities and enduring myths of the West.

From Idaho Mines to Chicago Studios: Early Life and Influences

Elling William Gollings entered the world in Pierce City, Idaho, a mining town that perhaps subtly shaped his early interests. His father was involved in mining, and young Elling initially harbored ambitions related to mechanics and the mining industry. However, fate, personal inclination, and circumstance steered him towards a different path. Following the early death of his mother, Gollings spent two formative years living with his grandmother before eventually relocating to Chicago to live with his father and stepmother.

It was during his schooling in Chicago that his artistic inclinations began to surface more formally. He received instruction in perspective drawing, a fundamental skill that would serve him well throughout his career. Even before this, however, the seeds of artistic ambition were sown. Gollings was captivated by the illustrations of the renowned Western artist Frederic Remington, whose dramatic depictions of frontier life filled the pages of popular magazines. This early admiration for Remington would remain a lifelong influence, shaping his thematic interests and perhaps his desire to portray the West with vigor and accuracy.

Another significant early influence was closer to home: his older brother, Oliver Gollings, was also pursuing painting. Seeing his brother engage in artistic creation likely provided encouragement and validation for Elling's own burgeoning talents. These combined factors – formal instruction, admiration for established artists, and familial example – coalesced, diverting him from the mines and machinery of his initial interest towards the canvas and brush. He completed his secondary education in Chicago, setting the stage for a more dedicated pursuit of art.

Formal Training at the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts

Recognizing the need for formal training to hone his natural abilities, Gollings enrolled in The Chicago Academy of Fine Arts around 1905. This institution, distinct from the larger Art Institute of Chicago, was known for its practical, commercially oriented arts education as well as fine arts instruction. His time at the Academy provided him with a solid grounding in drawing, painting techniques, and composition, equipping him with the technical proficiency necessary to translate his visions onto canvas and paper.

Studying art in a major urban center like Chicago presented a stark contrast to the Western landscapes and lifestyles that would become his primary subject matter. Yet, this formal education was crucial. It provided him with the tools and discipline to move beyond mere sketching or amateur rendering. He learned the academic principles that underpin representational art, which he could then adapt and apply to his chosen themes. This period of focused study refined his eye, steadied his hand, and broadened his understanding of art history and practice.

The decision to seek formal training underscores Gollings' seriousness about his artistic path. While deeply drawn to the authenticity of the West, he understood the value of academic discipline in effectively communicating his experiences and observations. His time in Chicago equipped him not just with skills, but likely also with exposure to a wider range of artistic styles and ideas, even as his heart remained firmly rooted in the landscapes and narratives of the American West.

Wyoming Beckons: Establishing a Career in Sheridan

After completing his studies in Chicago, Gollings felt the pull of the West strongly. He chose Sheridan, Wyoming, as the place to establish his career and make his home. This decision was pivotal. Sheridan, located in the heart of rich ranching country near the Bighorn Mountains, offered him direct access to the subjects he wished to paint: working cowboys, vast landscapes, Native American life, and the daily rhythms of a Western town. It provided the authenticity he craved, allowing him to live among and observe the people and places he depicted.

Around 1909, Gollings established his own studio in Sheridan. This space became his base of operations, where he translated sketches made outdoors and observations gathered from ranch work and local life into finished paintings and prints. Living in Wyoming allowed him to immerse himself in the environment. He didn't just paint cowboys; he reportedly worked as one at times, gaining firsthand knowledge of the skills, hardships, and camaraderie involved in ranch life. This direct experience infused his work with a credibility and detail that resonated with viewers familiar with the West.

His presence in Sheridan also connected him with the local community and the broader network of Western enthusiasts. He became a known figure, the "Cowboy Artist" whose work captured the essence of their region and lifestyle. This connection to place was fundamental to his artistic identity and output, providing both inspiration and subject matter throughout his most productive years.

Artistic Philosophy and Style: Capturing Reality

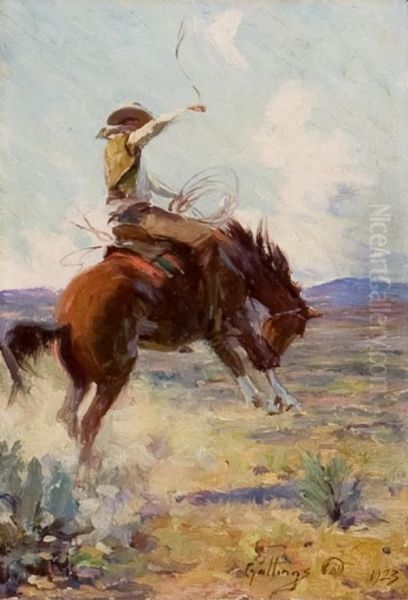

Elling William Gollings was fundamentally a realist. His artistic philosophy centered on depicting the West as he knew it, focusing on the accuracy of details in gear, anatomy (especially horses), and action. While influenced by the drama of Frederic Remington and the narrative richness of Charles M. Russell, Gollings carved out his own stylistic niche. His work often emphasized the everyday aspects of Western life – the quiet moments of contemplation on the range, the steady work of moving cattle, the interaction between rider and horse – as much as the more dramatic events.

His style is characterized by competent draftsmanship and a keen observational eye. He paid close attention to the way light fell on the plains and mountains, the specific postures of working cowboys, and the powerful musculature of horses in motion. While perhaps less overtly romantic or idealized than some of his contemporaries, Gollings' work possesses a quiet dignity and a deep respect for his subjects. He aimed to portray the West authentically, without excessive embellishment, allowing the inherent drama and beauty of the scenes to speak for themselves.

Compared to Russell, whose work often incorporated more storytelling and historical narrative, Gollings frequently focused on capturing a specific moment or activity with precision. His figures are typically well-integrated into their landscape settings, emphasizing the relationship between humans, animals, and the vast environment they inhabited. This commitment to observed reality, filtered through his artistic sensibility, gives his work its enduring power and documentary value.

Mastery Across Mediums: Oil, Watercolor, and Etching

Gollings demonstrated proficiency across several artistic mediums, adapting his technique to suit the subject and desired effect. Oil painting formed a significant part of his output, allowing him to build up rich colors and textures, ideal for capturing the substantiality of the Western landscape and the dramatic play of light and shadow. His oils often possess a solidity and depth well-suited to depicting the ruggedness of the terrain and the figures within it.

He was also adept with watercolor, a medium that lends itself to capturing atmospheric effects and conveying a sense of immediacy. Watercolors may have been particularly useful for field sketches or for works where a lighter, more fluid touch was desired. This versatility allowed him to approach different subjects with the appropriate tools, showcasing a breadth of technical skill.

A particularly important development in his later career was his adoption of etching. Encouraged and reportedly instructed by his friend and fellow Sheridan artist, Hans Kleiber, Gollings took up etching around 1926. Kleiber himself was a master printmaker, known for his depictions of wildlife and landscapes. Etching allowed Gollings to explore line work in a different way, creating multiple originals and reaching a wider audience through prints. His etchings often focus on dynamic compositions featuring horses and riders, demonstrating his strong drafting skills in this demanding medium. This expansion into printmaking added another dimension to his artistic practice and legacy.

The Cowboy's World: Life on the Range

The figure of the cowboy is central to much of Elling William Gollings' work. Having lived and worked alongside them, he depicted cowboys not merely as romantic icons, but as skilled laborers engaged in the demanding tasks of managing cattle, navigating vast landscapes, and handling horses. His paintings and prints capture the full spectrum of cowboy life, from the action-packed intensity of a roundup or rodeo to the solitary vigilance of a line rider checking fences.

Gollings had a particular gift for portraying horses, understanding their anatomy and movement with an expert eye. His horses are not generic representations but living creatures, conveying power, grace, and personality. The relationship between rider and horse, a fundamental aspect of Western life, is often a key element in his compositions. He captured the subtle communication and mutual reliance between human and animal with sensitivity and accuracy.

His famous 1931 poster for the Sheridan-Wyo-Rodeo exemplifies his ability to capture the energy and excitement of cowboy competition. However, many of his works focus on the less glamorous, day-to-day realities of ranch work. Paintings like The Line Riders showcase the often solitary and challenging nature of maintaining vast cattle operations. Through these depictions, Gollings provided an invaluable visual record of the skills and routines that defined the working cowboy's existence in the early 20th century, contributing significantly to the genre also populated by artists like Will James, who similarly lived the life he depicted.

Portraying Native Americans and the Western Environment

While renowned for his depictions of cowboys, Gollings also turned his attention to the Native American inhabitants of the region and the encompassing Western environment. His portrayals of Native Americans are generally observational and respectful, often depicting them within the landscape, engaged in traditional activities or adapting to the changing world around them. Works like The Smoke Signal (one of his Capitol murals) reflect common themes in Western art, but his approach aimed for accuracy in attire and representation, avoiding stereotypical exaggerations. He painted the Crow and Cheyenne people he would have encountered in the Sheridan area.

The landscape itself was more than just a backdrop in Gollings' art; it was an active participant. He skillfully rendered the vast sagebrush plains, rolling hills, and dramatic mountain ranges of Wyoming, capturing the unique light and atmosphere of the high plains. His understanding of the environment – the harsh weather, the changing seasons, the sheer scale of the land – informed his depictions of the people and animals who lived within it. His landscapes convey both the beauty and the challenges of the Western terrain.

In this focus on the interplay between figures and environment, Gollings joins a long tradition of Western art. While earlier artists like Albert Bierstadt and Thomas Moran emphasized the sublime grandeur of the West, Gollings, like contemporaries such as Maynard Dixon, often focused on the more intimate relationship between the land and its inhabitants, showing how the environment shaped their lives and work.

Major Commissions and Recognizable Works

Gollings' reputation earned him significant commissions and produced several iconic works. Perhaps most notable are the four large murals he was commissioned to paint for the Wyoming State Capitol Building in Cheyenne. Completed in the late 1920s, these murals depict key themes and events from Wyoming history and Western life. Titles often associated with these murals include The Smoke Signal, The Overland Emigrants, Indian Buffalo Hunt, and The Wagon Box Fight. These large-scale works cemented his status as a major Wyoming artist and remain important public examples of his art.

Beyond the murals, specific paintings stand out in his oeuvre. Sagebrush Jaunt, an oil painting from 1923, exemplifies his ability to capture the movement of horse and rider through the characteristic Wyoming landscape. It showcases his skill in rendering equine anatomy and the texture of the high desert environment. Another work that gained attention, partly due to its performance at auction, is The Line Riders, which fetched a significant price, highlighting the market's recognition of his artistic value.

His 1931 Sheridan-Wyo-Rodeo poster, though perhaps giving a narrower impression of his overall artistic range if viewed in isolation, became widely known and is a sought-after piece of Western ephemera. It demonstrates his ability to create dynamic, commercially appealing imagery capturing the excitement of rodeo culture. These works, along with numerous other paintings, watercolors, and etchings held in public and private collections, form the core of his artistic legacy.

Collaboration, Community, and Commerce

While largely forging his own path, Gollings was part of an artistic community and engaged in collaborations that extended his reach. His friendship with fellow Sheridan artist Hans Kleiber was particularly significant. Kleiber, primarily known for his etchings of wildlife and landscapes, not only provided camaraderie but also technical guidance, playing a key role in Gollings' adoption of etching as a medium. This relationship highlights the supportive network that could exist even in relatively isolated Western towns.

Gollings also interacted with other figures in the art world. The artist Edward Borein, another prominent painter and etcher of Western scenes, reportedly met Gollings and acquired some of his work, indicating mutual respect among artists working within the same genre. Such connections, sometimes facilitated by patrons or collectors like the Gallatin family mentioned in relation to Borein, helped artists gain recognition beyond their immediate locale.

Recognizing the potential for broader dissemination of his work, Gollings entered into a business partnership with Rex Schnitger. Together, they founded The Range Land Publishing Company in Sheridan. This venture published reproductions of Gollings' paintings, likely as prints and postcards. This entrepreneurial effort allowed his images of Wyoming and the West to reach a wider audience, making his art more accessible and contributing to the popular visual culture of the American West. It demonstrated an understanding of the commercial aspects of being a working artist.

Peers, Influences, and the Western Art Context

Elling William Gollings worked during a golden age of American Western art, alongside many other talented artists who sought to capture the essence of the region. His lifelong admiration for Frederic Remington placed him firmly within the tradition of illustrative and narrative Western art. He shared the stage with the towering figure of Charles M. Russell, whose Montana-based work often paralleled Gollings' Wyoming subjects, though with Russell's distinct storytelling flair.

Gollings' focus on authenticity and lived experience connects him to artists like Will James, who was both a writer and artist depicting the cowboy life he knew intimately. His realistic style and attention to detail can be compared to contemporaries like Frank Tenney Johnson, known for his nocturnes and depictions of cowboys, or W. Herbert Dunton, one of the Taos Society artists who also painted wildlife and Western figures with clarity.

While distinct from the more modernist or stylized approaches of some Taos artists like Ernest L. Blumenschein or Oscar E. Berninghaus, or the distinctive regionalism of Maynard Dixon, Gollings shared their dedication to Western themes. His work also stands alongside illustrators like N.C. Wyeth, whose dramatic Western scenes reached wide audiences. Gollings' specific contribution lies in his deep focus on Wyoming, his firsthand experience, and his versatile output across multiple mediums, offering a unique and valuable perspective within this rich artistic landscape. His connection with Hans Kleiber and Edward Borein further situates him within the network of working Western artists of his time.

Personal Glimpses: Character and Life Beyond the Canvas

Details about Elling William Gollings' personal life remain relatively scarce compared to the extensive documentation of his artistic output. Sources describe him as a tenacious and focused individual, dedicated to his craft. His decision to pursue art despite early interests elsewhere, his move to Wyoming to immerse himself in his subject matter, and his consistent production suggest a strong sense of purpose and determination.

Evidence suggests he kept diaries and corresponded, leaving behind written records that offer glimpses into his thoughts, experiences, and the process behind his art. These personal documents, where available, provide valuable context for understanding the man behind the paintings and prints, chronicling his life on the range and in his Sheridan studio.

His personal relationships included a marriage to Mauve Scrivner, though this union was reportedly brief, lasting only about a year. The reasons for its short duration are not widely documented, but it hints at the complexities and perhaps the demanding nature of his life as a dedicated artist in the West. Overall, the image that emerges is of a man deeply committed to his artistic vision, finding fulfillment and identity through his work documenting the world around him. His legacy is primarily defined by his art rather than by dramatic personal anecdotes.

Later Life and Enduring Legacy

Elling William Gollings continued to paint and etch actively throughout the 1920s and into the early 1930s, remaining based in Sheridan, Wyoming. His work ethic appears consistent, and he produced a significant body of work during this period, including the important Wyoming Capitol murals and his expansion into etching. His reputation as a key chronicler of the Wyoming scene was well-established.

His life came to an end on April 16, 1932, in Sheridan, the town that had been his home and inspiration for over two decades. He was only 54 years old. His death marked the loss of an important voice in American Western art, an artist who had witnessed and documented the transition of the West with an authentic and skilled hand.

Gollings' legacy endures through his artwork, which is held in numerous public and private collections. The University of Wyoming Art Museum, the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody, Wyoming, and the Wyoming State Museum are among the institutions that preserve and exhibit his work. His paintings, watercolors, and etchings continue to be appreciated for their historical accuracy, artistic merit, and evocative portrayal of the landscapes, people, and animals of the American West. He is remembered as a true "Cowboy Artist," whose direct experience informed every brushstroke and etched line, leaving behind a valuable and enduring vision of Wyoming and the closing frontier era. His work inspired later collectors and enthusiasts, ensuring his contribution to Western art continues to be studied and admired.

Conclusion: A Lasting Vision of the West

Elling William Gollings occupies a vital place in the history of American Western art. As an artist deeply embedded in the Wyoming landscape and culture during the early 20th century, he brought a unique blend of formal training and firsthand experience to his work. His dedication to realism, his keen eye for detail, and his versatile skills across oil, watercolor, and etching allowed him to create a rich and authentic portrait of the West.

From the daily lives of working cowboys and the majestic presence of horses to the specific light and feel of the Wyoming plains and mountains, Gollings captured a world that was rapidly changing. His work serves not only as fine art but also as invaluable historical documentation. While influenced by giants like Remington and working alongside contemporaries like Russell and Kleiber, Gollings developed his own distinct voice, characterized by its quiet authenticity and deep respect for his subjects.

Through his paintings, his widely recognized Wyoming State Capitol murals, and his later etchings, Gollings ensured that his vision of the West would endure. His legacy is that of a dedicated craftsman and an honest observer, an artist who truly knew the life he depicted. Elling William "Bill" Gollings remains a significant figure, celebrated for his contribution to preserving the visual heritage of the American West, particularly the unique character of Wyoming.