Charles Maurin (1856-1914) stands as a fascinating, if for a time overlooked, figure in the vibrant tapestry of late 19th and early 20th-century French art. An artist of diverse talents and evolving styles, Maurin navigated the dynamic Parisian art world, leaving behind a body of work that skillfully blended elements of Realism with the burgeoning Symbolist movement. His contributions as a painter and an innovative printmaker, particularly in color techniques, alongside his connections with prominent contemporaries, mark him as an artist deserving of renewed appreciation. This exploration delves into the life, art, and enduring legacy of Charles Maurin, a quiet innovator at the heart of a revolutionary period in art history.

Early Life and Academic Foundations

Born in Le Puy-en-Velay in the Auvergne region of France in 1856, Charles Maurin's artistic journey began with a traditional academic grounding. His early promise was recognized when he was awarded the prestigious Prix Crozatier in 1875. This accolade was not merely an honor; it provided him with the crucial financial means—a three-year scholarship—to pursue advanced artistic studies in Paris, the undisputed epicenter of the art world at the time.

Upon arriving in Paris, Maurin immersed himself in the rigorous training offered by two of the most respected institutions: the École des Beaux-Arts and the Académie Julian. At the École des Beaux-Arts, he would have been exposed to the classical traditions and technical discipline emphasized by masters like Jean-Léon Gérôme or Alexandre Cabanel, who, though representing an older guard, still held considerable sway. The Académie Julian, on the other hand, was known for a slightly more liberal atmosphere, attracting a diverse international student body and faculty that included figures like William-Adolphe Bouguereau and Jules Lefebvre. This dual education provided Maurin with a solid technical foundation in drawing and painting, which would underpin his later, more experimental endeavors.

Initially, Maurin's artistic output focused on portraiture, a genre that demanded keen observational skills and the ability to capture a sitter's likeness and character. This early phase honed his draughtsmanship and his understanding of human anatomy and expression, skills that would remain evident throughout his career, even as his thematic concerns and stylistic approaches evolved.

Parisian Immersion and Artistic Evolution

The Paris that Charles Maurin entered was a crucible of artistic innovation and intellectual ferment. The Impressionist movement, with artists like Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Edgar Degas, had already challenged academic conventions, and new currents were constantly emerging. Maurin, while rooted in his academic training, was not immune to these transformative influences. His artistic curiosity led him to explore themes beyond formal portraiture, delving into the multifaceted life of Paris, particularly the bohemian enclave of Montmartre.

Montmartre, with its cabarets, dance halls, artist studios, and vibrant street life, became a rich source of inspiration for Maurin, as it was for many of his contemporaries. He began to depict the everyday lives of its inhabitants, often focusing on women and children. These were not idealized or romanticized portrayals but rather intimate glimpses into private moments and social realities, reflecting a growing interest in social philosophy and the human condition. His works from this period often carry a subtle narrative, hinting at the inner lives and circumstances of his subjects.

This shift in subject matter was accompanied by an evolution in his artistic style. While maintaining a degree of realism in his depictions, Maurin began to incorporate elements that resonated with the burgeoning Symbolist movement. Symbolism, championed by artists like Gustave Moreau, Odilon Redon, and Puvis de Chavannes, sought to express ideas, emotions, and subjective experiences through suggestive imagery and metaphorical content, moving away from the purely objective representation of the Impressionists or the stark social commentary of earlier Realists like Gustave Courbet.

The Allure of Montmartre and Influential Friendships

Maurin's engagement with Parisian life, especially in Montmartre, was not solely observational; he became an active participant in its artistic and social circles. He frequented the cafés and cabarets that were hubs of avant-garde activity, such as the famed Le Chat Noir, a gathering place for artists, writers, and performers. It was in these environments that he forged significant friendships that would shape his career and personal life.

Among his closest associates were Félix Vallotton and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Vallotton, a Swiss-born artist who would later become associated with Les Nabis, found in Maurin a mentor and a friend. Maurin played a crucial role in Vallotton's artistic development, particularly by introducing him to the techniques of woodcut printing, a medium in which Vallotton would achieve great renown. Their shared interests and mutual respect fostered a strong bond.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, the quintessential chronicler of Montmartre's nightlife, was another key figure in Maurin's circle. Their friendship was rooted in their shared fascination with the district's unique atmosphere and its colorful denizens. They moved in similar social spheres, and their artistic paths, while distinct, often intersected. Maurin, Lautrec, and Vallotton even exhibited together in 1893, showcasing their individual responses to the modern urban experience. These connections provided Maurin with both intellectual stimulation and a supportive network within the competitive Parisian art scene. His interactions with these artists, and others like Edgar Degas, whom he admired, undoubtedly enriched his artistic perspective.

A Unique Stylistic Synthesis: Realism Meets Symbolism

Charles Maurin's mature artistic style is characterized by a distinctive fusion of Realist observation and Symbolist introspection. He did not fully abandon the representational clarity of his academic training, but he imbued his subjects with a deeper psychological resonance and often a subtle allegorical dimension. His approach was described as conservative yet unique, a testament to his ability to synthesize diverse influences into a personal visual language.

His depictions of modern life, particularly scenes involving women and children, often featured exaggerated curves and a palette of soft, harmonious tones. These stylistic choices contributed to the intimate and often tender mood of his compositions. Whether portraying a mother and child in a quiet domestic setting or a solitary female figure lost in thought, Maurin demonstrated a remarkable sensitivity to the nuances of human emotion and interaction. His work often explored themes of maternity, childhood innocence, and the complexities of female experience in a rapidly changing society.

One of his most significant large-scale works, L'aurore du travail (The Dawn of Labor), exemplifies his engagement with social themes through a Symbolist lens. This allegorical painting, depicting miners, reflects his concern for the working class and the dignity of labor, themes also explored by earlier Realists like Jean-François Millet. However, Maurin's treatment infuses the scene with a symbolic weight, elevating it beyond mere social documentation to a more universal statement about human endeavor and resilience. The composition and the heroic portrayal of the figures lend the work a monumental quality, characteristic of some Symbolist ambitions.

Pioneering Printmaking: Innovations in Color

Beyond his work as a painter, Charles Maurin made significant contributions to the art of printmaking. He began with black and white etchings, a medium that allowed him to explore line and tone with precision. His early etchings often captured the gritty reality and atmospheric charm of Montmartre, showcasing his keen eye for detail and his ability to evoke a strong sense of place.

However, Maurin was an innovator at heart, and he soon turned his attention to the possibilities of color printmaking. He became one of the first French artists to design and execute color lithographs and to experiment extensively with multi-plate color etching. This was a technically demanding field, requiring a sophisticated understanding of color separation and printing processes. His foray into color printmaking coincided with a broader surge of interest in the medium, partly fueled by the influence of Japanese Ukiyo-e prints (Japonisme), which captivated many artists of the era, including Mary Cassatt, Edgar Degas, and Toulouse-Lautrec himself, with their bold compositions and flat planes of color.

Maurin's color prints, like his paintings, often focused on intimate scenes of daily life, particularly featuring women and children. The use of color added a new dimension to his work, enhancing its emotional impact and decorative qualities. His technical experimentation in this area placed him at the forefront of a revival in original printmaking, where artists sought to elevate prints from mere reproductions to independent works of art. His efforts contributed to the rich landscape of fin-de-siècle printmaking, alongside contemporaries like Jules Chéret, known for his vibrant posters, and Théophile Steinlen, another chronicler of Montmartre life.

Key Themes and Representative Works

Several recurring themes define Charles Maurin's oeuvre, reflecting his artistic preoccupations and his engagement with the social and cultural currents of his time.

The Intimacy of Domestic Life: A significant portion of Maurin's work is dedicated to portraying women and children in everyday settings. Works often titled Maternité (Maternity) or depicting tender interactions between mothers and their offspring showcase his ability to capture moments of profound intimacy and affection. These scenes are rendered with a delicate touch, emphasizing the emotional bonds and the quiet dignity of domestic life. His sensitive portrayal of these subjects aligns him with other artists of the period, like Berthe Morisot or Mary Cassatt, who also explored themes of modern womanhood and childhood, though Maurin's style retained its unique blend of Realism and Symbolist undertones.

L'aurore du travail (The Dawn of Labor): This monumental work stands as a powerful statement on the lives of working-class individuals. As mentioned, it depicts miners, figures often associated with hardship and struggle. Maurin, however, imbues them with a sense of strength and resilience, suggesting a dawning of awareness or hope. The allegorical nature of the title and the heroic scale of the figures elevate the subject beyond simple genre painting, reflecting Symbolist tendencies to explore universal themes. This work demonstrates Maurin's capacity for ambitious, socially conscious art.

Scenes of Montmartre: While perhaps less overtly famous for these than Toulouse-Lautrec, Maurin's depictions of Montmartre life, particularly in his etchings, capture the unique atmosphere of the district. These works provide valuable visual records of the cabarets, streets, and people that defined this bohemian hub.

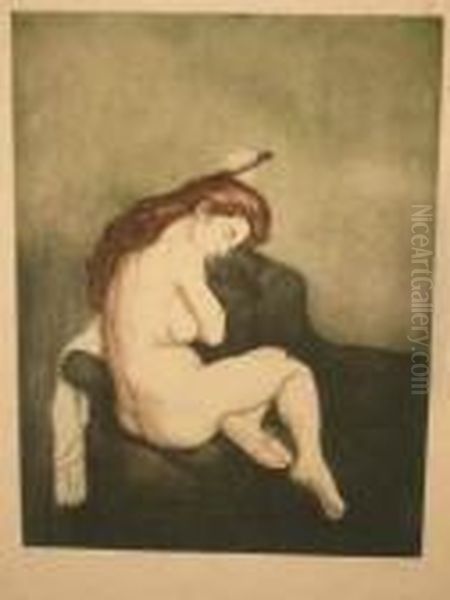

Femme nue (Nude Woman): Like many artists of his time, Maurin explored the female nude. His approach often combined classical sensibilities with a modern directness. Some of these works, while aesthetically refined, were occasionally perceived as daring or even provocative by contemporary standards, hinting at the evolving perceptions of the body and sensuality in art. An example, Femme nue, is held in the collections of the Musée d'Orsay, indicating its art historical significance.

Symbolic Compositions: Beyond specific, easily categorized themes, many of Maurin's works carry a symbolic charge. Even his more straightforward depictions of daily life can possess an enigmatic quality, inviting viewers to look beyond the surface. Works like Le lever du rêve (The Awakening of the Dream), if this title refers to a specific piece or a thematic concern, suggest an interest in the liminal space between reality and imagination, a core tenet of Symbolism.

Relationships with Contemporaries: Collaboration and Context

Maurin's position within the Parisian art world was solidified by his relationships with other artists. His friendship with Félix Vallotton was particularly significant. Maurin's guidance in woodcut techniques was instrumental for Vallotton, who went on to become a master of the medium, known for his stark black-and-white contrasts and incisive social commentary. This mentorship highlights Maurin's generosity and his own technical expertise. Vallotton, in turn, became associated with Les Nabis, a group that included Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard, artists who also focused on intimate, domestic scenes and decorative compositions, albeit with a different stylistic emphasis than Maurin.

His connection with Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec placed him at the heart of Montmartre's avant-garde. While Lautrec's style was more graphic and satirical, their shared environment and mutual respect fostered a productive artistic dialogue. They both captured the fleeting moments and unique characters of Parisian nightlife, though Maurin's approach was often more introspective and less overtly theatrical than Lautrec's celebrated posters and paintings.

Maurin's admiration for Edgar Degas is also noteworthy. Degas, an Impressionist who stood somewhat apart from the core group, was known for his innovative compositions, his focus on modern urban subjects like ballet dancers and café scenes, and his own experiments with printmaking. Maurin likely found inspiration in Degas's ability to capture the dynamism of contemporary life and his sophisticated use of line and form.

The broader artistic context included figures like Gustave Moreau, whose richly detailed and mythological paintings were a cornerstone of Symbolism, and Odilon Redon, known for his dreamlike and often unsettling charcoal drawings (noirs) and later, his vibrant pastels. While Maurin's style was generally more grounded in reality than these Symbolist masters, he shared their interest in conveying subjective experience and exploring the inner world. He also operated in a milieu where the legacy of Realists like Gustave Courbet and Jean-François Millet still resonated, particularly in their commitment to depicting the lives of ordinary people and laborers.

The printmaking revival saw artists like Jules Chéret revolutionizing poster art with his vibrant color lithographs, and Théophile Steinlen creating poignant images of Montmartre life and social issues, often for publications and posters. Maurin's own innovations in color printmaking contributed to this flourishing of the graphic arts.

Later Years, Obscurity, and Rediscovery

Despite his active participation in the Parisian art scene and the respect he garnered from influential peers, Charles Maurin's work gradually faded from public prominence after his death in 1914. This period of obscurity was not uncommon for artists who did not fit neatly into the dominant narratives of art history, or whose styles were perceived as transitional or eclectic. The early 20th century saw the rise of radical movements like Fauvism and Cubism, which overshadowed many artists of the preceding generation.

For many decades, Maurin remained a figure known primarily to specialists and connoisseurs. However, in more recent times, there has been a growing scholarly and curatorial interest in reassessing artists who operated outside the most famous avant-garde circles or who bridged different stylistic movements. This has led to a rediscovery of Charles Maurin's contributions. Art historians and museums have begun to re-examine his oeuvre, recognizing the quality of his work, his technical innovations in printmaking, and his unique synthesis of Realist and Symbolist sensibilities.

Exhibitions and publications have slowly brought his art back into the light, allowing a new generation to appreciate his subtle portrayals of Parisian life, his sensitive depictions of women and children, and his pioneering work in color prints. His paintings and prints are now found in museum collections, including the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, a testament to his enduring artistic merit.

Conclusion: The Enduring Art of Charles Maurin

Charles Maurin was an artist of quiet conviction and considerable skill, a painter and printmaker who carved out a distinctive niche in the bustling art world of fin-de-siècle Paris. He successfully navigated the currents of Realism and Symbolism, creating a body of work that is both a reflection of its time and possessed of a timeless appeal. His intimate portrayals of everyday life, particularly the lives of women and children, are imbued with a sensitivity and psychological depth that resonate with contemporary audiences. His pioneering efforts in color printmaking mark him as an important figure in the history of the graphic arts.

While his name may not be as widely recognized as some of his more famous contemporaries like Toulouse-Lautrec or Degas, Maurin's contributions are undeniable. He was a valued friend and mentor to artists like Félix Vallotton, and an active participant in the cultural life of Montmartre. His art offers a unique window into the social and artistic concerns of his era, characterized by its thoughtful engagement with the human condition, its technical finesse, and its subtle blend of observation and imagination. As art history continues to broaden its scope and re-evaluate figures from the past, Charles Maurin's legacy as a skilled, innovative, and deeply human artist is rightfully being restored. His work serves as a reminder that the story of art is often found not just in the grand pronouncements of major movements, but also in the nuanced voices of individuals who forged their own paths.